CHARTING DAVID BOWIE’S LASTING INFLUENCE ON ELECTRONIC MUSIC

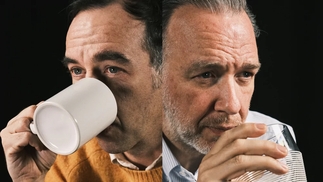

Tiga, DJ Hell, Boy George, Danny Howells and Soulwax talk about Bowie's impact...

When David Bowie returned at the beginning of the year with his first release in a decade — the fragile, tender, Berlin-referencing single ‘Where Are We Now?’ — he was met with near-universal acclaim. News of a new album, ‘The Next Day’, swiftly followed, and rapturous appraisals of probably the most important and influential musical artist in the last 40 years have flowed from virtually every media outlet.

But what has been largely overlooked is Bowie’s influence on electronic music — and many of the key figures that have helped shape the dance scene into what it is today. Indeed, it is arguable that without Bowie, club culture wouldn’t be as free and expressive as it is in 2013.

“David Bowie is the biggest inspiration on my career up until now,” says DJ Hell, whose Gigolos label was instrumental in the breakthrough of ‘electroclash’ in the early noughties, “He combined music, art, fashion and performance into the future.”

“His influence on electronic music is just immense,” believes house DJ Danny Howells, another jock who you’ll often see wearing a Bowie t-shirt of some sort. “And you just have to look at people like Tiga to realise that the Bowie influence still runs strong today.”

“Bowie’s impact on me as an artist and producer was massive,” self-styled Canadian electro darling Tiga tells DJ Mag. “For years he was the personification of the dream. His intelligence, his freedom, the songs, the looks, his voice — Bowie has it all in a way almost nobody else ever had.”

TABOO-BREAKER

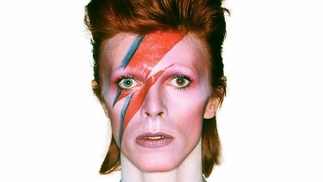

It was Bowie’s ability to experiment, trend-spot, paint lyrical images and create new personas — chameleon-like — in the '70s that gave him such a cult following. After dalliances with folk, rock and mod sounds in the late ‘60s, Bowie created his alien-like Ziggy Stardust character in the early ‘70s. With his dyed-red spiky hair and psychedelic catsuits, he effectively kicked off the glam movement with old mod cohort Marc Bolan, who became T-Rex. Bowie’s gender-bending persona coincided with his declaration in a 1972 interview with Melody Maker that he was gay.

This was at a time when, post-Stonewall Riot in the US, the gay liberation movement was starting to assert the rights of gay people and calling for an end to discrimination. Bowie wasn’t really gay, more "a taboo-breaker and a dabbler who mined sexual intrigue for its ability to shock" — as his biographer David Buckley would have it — but by aligning himself to the embryonic gay scene, on whose dancefloors disco was being formulated, he indirectly gave strength to the movement.

His subsequent appearance on UK music chart show Top Of The Pops singing ‘Starman’, flouting the conservative moral codes of the day, was a revelation to thousands of oddball and misfit teenagers in the suburbs of UK cities.

“I saw Bowie when I was 11 at Lewisham Odeon, it was the penultimate gig before he killed Ziggy,” Bowie fan Boy George tells DJ Mag. “That was the beginning of my Bowie obsession, and I used to go and sit outside his house in Beckenham, I was a proper hardcore fan — and still really am, obviously.

“I wouldn’t go and sit outside his house now, but he really changed my life as a kid, because back then living in suburbia and being gay, knowing I was different — and being told I was different by other kids — seeing Bowie was like a light at the end of the tunnel,” continues the DJ/singer. “It was like, ‘Wow, I’m not the only one that’s a weirdo’.He was the godfather of all weirdoes.”

Anyone who felt disenfranchised or different, Bowie spoke to you. “A lot of people over the years have said, ‘Well, he wasn’t really gay, he just used the gay thing’, but it doesn’t matter because it was such a radical thing to do,” George adds. “Bowie definitely opened that Pandora’s box.”

BERLIN TRILOGY

Bowie quickly killed off his Ziggy persona in 1973, releasing the great ‘Aladdin Sane’ album that featured his face on the cover sporting an iconic multi-coloured lightning flash. He moved to America in 1974, releasing the ‘Diamond Dogs’ album that referenced George Orwell’s dystopian 1984 novel, and then with ‘Young Americans’ he moved into “plastic soul”, recording in Philadelphia with soul, funk and disco musicians and beginning to formulate his Thin White Duke persona. Throughout the '70s, every new Bowie album was An Event, and the way he switched styles each time could be said to mimic the way a DJ — such as this issue’s cover star Damian Lazarus, for instance — will effectively bend genres to embrace the latest new sounds.

“[1976 album] 'Station To Station', the title track especially, was a huge turning point,” thinks Danny Howells. “The mood that the intro creates sets the tone for the entire album and gives an indication of what was to follow with ‘Low’.”

By the mid-‘70s, Bowie had a massive cocaine habit, and — becoming somewhat delusional, as depicted in Alan Yentob’s BBC film The Cracked Actor — he moved to Berlin to explore his interest in the growing German music scene. ‘Low’ was particukarly influenced by electronic pioneers Kraftwerk, and krautrockers such as Neu! and Can.

“Just the entire concept of dividing an album into short poppy song fragments and ambient wordless instrumentals was an eye-opener to me, especially at such a young age,” says Danny Howells of ‘Low’.

“And the depth of the material on side two was astonishing. For a mainstream artist to take this kind of music to the masses was one of the bravest steps since ‘Revolution 9’ [avant-garde track on ‘The White Album’ by The Beatles]". “When I first heard ‘Low’, I remember thinking, ‘What’s he done? What is this record?’ Momentarily I was horrified, but then literally overnight I realised that it was an amazing record,” says Boy George.

“I saw Kraftwerk recently at the Tate and I hadn’t noticed how much ‘Warszawa’ from ‘Low’ has the same keyboard sound as Kraftwerk. It was shameless in a way, but radical for someone like Bowie to embrace that sound.”

NEW ROMANTICS

Bowie's second Berlin album ‘Heroes’, while still experimental, was more rockist, while ‘Lodger’ had a song called ‘DJ’ on it — “I am a DJ, I am what I play” — and also included ‘African Night Flight’, which was a direct precursor to the influential, amazing ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’ by David Byrne (from Talking Heads) and Brian Eno. “It's not just his work on ‘Low’, ‘Heroes’ and ‘Lodger’ that influences, though,” reckons Danny Howells, “but also his amazing production work for Iggy Pop from that period — especially on ‘The Idiot’. “‘Nightclubbing’ is the most obvious reference, but ‘Dum Dum Girls’ and the amazing ‘Mass Production’ are astonishing, and laid the blueprint for people like Gary Numan and so on.

” Ever part of the zeitgeist, Bowie had also co-produced Iggy & The Stooges in the early ‘70s, as well as Lou Reed’s first solo album, the transgressive ‘Transformer’. And written 'All The Young Dudes' by Mott The Hoople. “I don't think the early ‘80s New Romantic thing — Visage, Human League, Associates, Culture Club etc — would have happened if it hadn't been for Bowie's music, along with his images,” Danny Howells continues. “A lot of the key players of that period, the likes of Steve Strange, were also involved in the emergence of UK club culture.”

Steve Strange, a young ex-punk from Wales, started a club called Heroes (named after the Bowie track) at the tail-end of the '70s, which would soon become the Blitz Club. “Everyone was disillusioned with punk, and looking for a new club launch,” club impresario Strange tells DJ Mag. “Everyone seemed to look up to Bowie, so we played a lot of his music — along with Roxy Music, Nina Hagen, Kraftwerk and so on. Heroes was like an homage to him.”

As young clubbers came dressed in increasingly outlandish garb, the Blitz Club soon became the epicentre for the New Romantic movement that spawned many of the early '80s synth-pop acts like Depeche Mode, Human League, and Steve Strange’s Visage.

Spandau Ballet, before they went all schmaltzy, were the in-house band, and Boy George, who would soon form Culture Club, ran the cloakroom at the Blitz. The club became the trendy, newsworthy place to be, and soon Bowie was visiting to scout for extras for his ‘Ashes To Ashes’ video. “We used to dance to Bowie’s ‘Fashion’ at the Blitz, it was an early club record made with machines,” says Boy George. “'Ashes To Ashes' in some respects wasn’t really a dance record, but it was embracing technology that was soon to become commonplace.

“The night that Bowie came to the Blitz, I was working in the cloakroom and people were acting like teenyboppers,” George continues. “I was too cool for school, I wasn’t going to run after him cos I’d done years of running after him and screaming, and I was a bit too cool now.

” The following night George met Bowie at the Beat Route on Wardour Street in Soho, and then at the Embassy Club with cross-dressing pal Marilyn. Marilyn immediately jumped on Bowie’s lap. “Bowie pushed him off, obviously,” says George, cattily. “Years later I did an internet chat with Bowie, and he actually said to me ‘How’s that hideous creature Marilyn?"

FUNK TO DRUM & BASS

The ‘Scary Monsters’ album was where Bowie combined artistic and electronic experimentation with pop accessibility, and it catapulted him back to superstardom. George wasn’t chosen to be in the No.1 selling ‘Ashes To Ashes’ video, but Steve Strange was, and when his Visage single ‘Mind Of A Toy’ came out around the same time it smashed into the UK Top 10. Strange (who has a new Visage album out soon) tells DJ Mag the convoluted story of filming the ‘Ashes To Ashes’ video with all the Blitz extras — “We thought we were going to be whisked off somewhere glamorous like the Bahamas, but when we spoke to the coach driver he said ‘Are you all ready for Southend?’ It was Southend, wasn’t it?” — and how Bowie was very down-to-earth and stayed in touch with him afterwards.

Visage, Gary Numan and Ultravox would soon themselves be cited as influences by the Belleville Three in Detroit — Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson — in their early techno productions, and the likes of Visage would also later influence Fischerspooner, Felix Da Housecat and La Roux, amongst others.

For his next album ‘Let’s Dance’, Bowie teamed with American funkateer Nile Rodgers from Chic — 30 years before Daft Punk did the same. The title track went to No.1, and the album that followed — ‘Tonight’ — also featured fusion tracks that would be played in discos and clubs, such as ‘Loving The Alien’ and ‘Blue Jean’.

Bowie then abandoned his solo career for the band project Tin Machine, anticipating the Britpop explosion of blokeish bands — Oasis, Blur, Suede etc — by a good few years. By 1993, though, he was back with Nile Rodgers for the ‘Black Tie White Noise’ album, that contained bits of soul, jazz and hip-hop, and then in 1995 he was reunited with Eno for the quasi-industrial ‘Outside’. Dance music was by now in full flow, and Bowie tapped into the emerging drum & bass scene for his next album, ‘Earthling’.

It was his first album recorded entirely digitally, created using guitar and sax samples and assorted chopped-up loops. The lead single ‘Little Wonder’ saw Bowie’s distinctive-sounding rhymes peppering Omni Trio-style Amen junglist breaks, while ‘Dead Man Walking’ was more rocktronic and Prodigy-esque. At Phoenix Festival in 1996 Bowie played a ‘secret’ gig in the dance tent under the name Tao Jones Index. Drum & bass don Goldie, who Bowie had befriended, was there to see it, and in turn Bowie was there to greet Goldie when the junglist came off stage after his own d&b set. Drum & bass suddenly had a mainstream stamp of approval.

SOULWAX

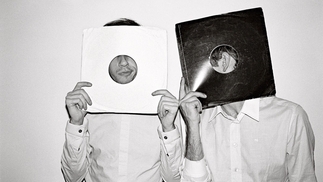

While ‘70s contemporaries like Rod Stewart and Elton John trod water, Bowie continued doing interesting things until a freakish incident where he got a lolly stick thrown by a fan at a gig, and then a fairly serious heart attack, led him to become a semi-recluse in New York. One thing he did do, however, was keep up-to-date with current trends via the internet, and he was one of the first to praise Soulwax’s 2ManyDJs project and their ‘Radio Soulwax’ mash-ups. Bowie was a regular poster on the Soulwax forum (although no-one believed it was him until years later), and when the Dewaele brothers came to craft the latest chapter of their Radio Soulwax project — 24 separate one-hour mixtapes — they just had to do one on Bowie.

As the Soulwax mix flits through ‘Fame’, ‘Sound & Vision’, ‘Golden Years’, ‘Fashion’, ‘DJ’, ‘Let’s Dance’ and so on, the superb accompanying film casts an androgynous woman as Bowie, drifting artfully through different scenes — an idea duplicated in Bowie’s latest video for ‘The Stars (Are Out Tonight)’, with actress Tilda Swinton.

“We felt like the whole spectrum of our record collection needed to be represented in those 24 hours,” David Dewaele from Soulwax tells DJ Mag, “and it just so happens that Bowie signifies an important part of it.” Chicago house, hardcore punk and ‘sad songs’ were other genres represented on the 24-hour Radio Soulwax app, but few artists are actually a genre of their own.

“The beauty of Bowie is that he transcends genres, so he is a hero of music and all art in general,” Soulwax say. “He has been such a driving force in popular — and underground — culture that it is very hard to gauge how influential he’s been,” David Dewaele continues. “In a way it's like asking how cellphones have influenced our lives. But if I think about it consciously, apart from the amazing and absolutely groundbreaking and touching music he has made over the years, it is also the way he went about his career, and the choices he made to push himself and his audience time and time again, that has been a very big influence on my brother and me.”

Bowie’s new album isn’t dubstep, or trap, although he does almost sample himself — by referencing his past — at various stages, including on the album artwork. Recorded with long-term producer Tony Visconti, although good, it’s not exactly reinventing the wheel this time around, but it just generally feels good to have Bowie — at 66 — back.

“Probably Kraftwerk influenced electronic music more than Bowie, but certainly Bowie was part of that transition,” Boy George concludes. “Bowie definitely wanted to be a star, but he also wanted to affect things. And I think that’s really the job of an artist — to try to shake up the status quo and give another point of view. You don’t want your stars to be pedestrian.”

“His obsession with Kraftwerk was filtered into a unique blend of electronic music and soul and rock and pop, and that Berlin trilogy has then itself influenced bands and genres subsequently,” say Soulwax. “This is the kind of stuff historians do for a living so I don't have any scientific evidence, and ‘influence’ is such an abstract concept to gauge, but my gut feeling is to say that Bowie has influenced electronic music in a big way.”

“Most important was the idea of filling your entire life with your art and music — without compromise,” says Tiga. “For the union of all the elements that so rarely sit together — quality music, art, money, even humour — nobody can touch him.”