GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #2

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

With a whole string of influential residencies during the ‘70s and ‘80s, Colin Curtis was a central figure in the development of 3 distinct movements (Northern soul, jazz-funk and house) - I can’t think of another DJ who’s replicated this feat. Curtis is perhaps the closest DJ the UK has, in terms of legacy and the outright respect he garnered from this contemporaries, to New York’s seminal disco selector David Mancuso. He continues to DJ at soul events in the UK, and is a presenter on Manchester’s New Sunset Radio.

Having started out in the late ‘60s, by the early ‘70s he’d begun to make his mark as part of the line-up at the Golden Torch, which hosted the leading Northern soul all-nighter of the time in his home city of Stoke-On-Trent. When The Torch closed in 1973 he struck up his legendary 5 year DJ partnership with Ian Levine at the Blackpool Mecca, which remained an essential port of call on the Northern circuit following the launch of Wigan Casino later that year. Many people would head to the Mecca, which closed at 2am, before moving on to the Casino, which opened for it’s all-nighters at the same time.

It was Levine and Curtis who brought about Northern soul’s infamous schism by playing contemporary ‘70s releases alongside ‘60s rarities. Many ‘soulies’ would have happily seen them burned at the stake for such heresy, but others embraced this progressive direction. Curtis would eventually step away from the Northern scene, quitting the Mecca in ‘78 to launch the region’s leading jazz-funk night of the late ‘70s at Rafters in Manchester, where he would strike up another memorable partnership with DJ John Grant.

During the next 5 years he would be a fixture at jazz-funk all-dayers throughout the North and Midlands, and very much a pioneer of the movement, unearthing rare jazz cuts with a similar zeal to how he rooted out Northern soul singles. It’s no surprise that Curtis would provide major inspiration to numerous jazz enthusiasts, not least a young Gilles Peterson back in the ‘80s.

In 1983 Curtis found his spiritual home at Manchester’s Berlin, hosting midweek sessions alongside another renowned jazz aficionado Hewan Clarke. The jazz-dance scene flourished here at a time when the new New York electro sound had become the dominant musical force on the specialist black music scene elsewhere in the North and Midlands – an approach Curtis would later adopt, alongside DJ Jonathan, at Nottingham’s Rock City.

His last key residency was The Playpen in Manchester during the mid-‘80s, again with Hewan Clarke. Including imports on the then new Chicago labels Trax and DJ International, he helped pioneer the fledgling UK house scene at its very roots, and directly influenced what was to happen a few years down the line at The Haçienda, destined to become the new era’s cathedral of rave.

During the 1980s Morgan Khan was viewed as a ‘dance music mogul’, a true instigator who enriched British culture via his unyielding efforts, driven by ‘an ego’, as Blues & Soul once put it, ‘bordering on the manic’ – Khan was (and remains) a force of nature.

In true one nation under a groove style, Khan’s label, Streetwave, which started putting out records in 1982, was inclusive, bringing black, white and Asian, straight and gay together under the banner of musical appreciation. My path would cross with Morgan’s in a major way a few years down the line when I approached him with some demos I’d recorded with a couple of Manchester musicians. This would result in the 1984 release of the ‘Street Sounds UK Electro’ compilation.

Streetwave was the inspiration for a whole host of independent British dance labels that would emerge later in the decade. Khan had started out with unbridled optimism intending to create a dance music dynasty in the unlikely location of London’s West Acton. His battle cry was; “Britain has for far too long been an importer of ‘dance’ music, turn the page man, ‘cos we’ve started a new chapter.”

This ‘new chapter’, however, wouldn’t quite work out the way Khan had envisaged - the big hit single he needed to ignite things failing to materialise. It was, however, through albums not singles that he finally struck gold, licensing the most popular imports that specialist DJs were playing and putting them onto compilations, most notably the ‘Street Sounds’ and the ‘Street Sounds Electro’ series. Khan’s stroke of genius was in making upfront dance music affordable – offering a whole LP for little more than the price of just one 12” import. The ‘Electro’ series perfectly chimed with the first wave of British breakdancers, the cassettes becoming ghetto-blaster classics as kids took to the lino in shopping centres throughout the land - the Bronx exploding on the streets of Blighty. ‘Street Sounds Electro’ also has the distinction of being the UK’s first series of mixed albums (most of these mixes credited to London’s Mastermind).

The label would score a remarkable 57 chart entries in just over 5 years (1983-1988), but this didn’t stop it from going into insolvency. This was said to be a result of losses incurred by Khan’s ill-fated club music magazine, Street Scene, which lasted just 6 months. Yet, just as people thought he was finished, Khan re-emerged for his ‘80s swansong, acquiring the UK licenses for Chicago’s most influential house music labels, DJ International and Trax.

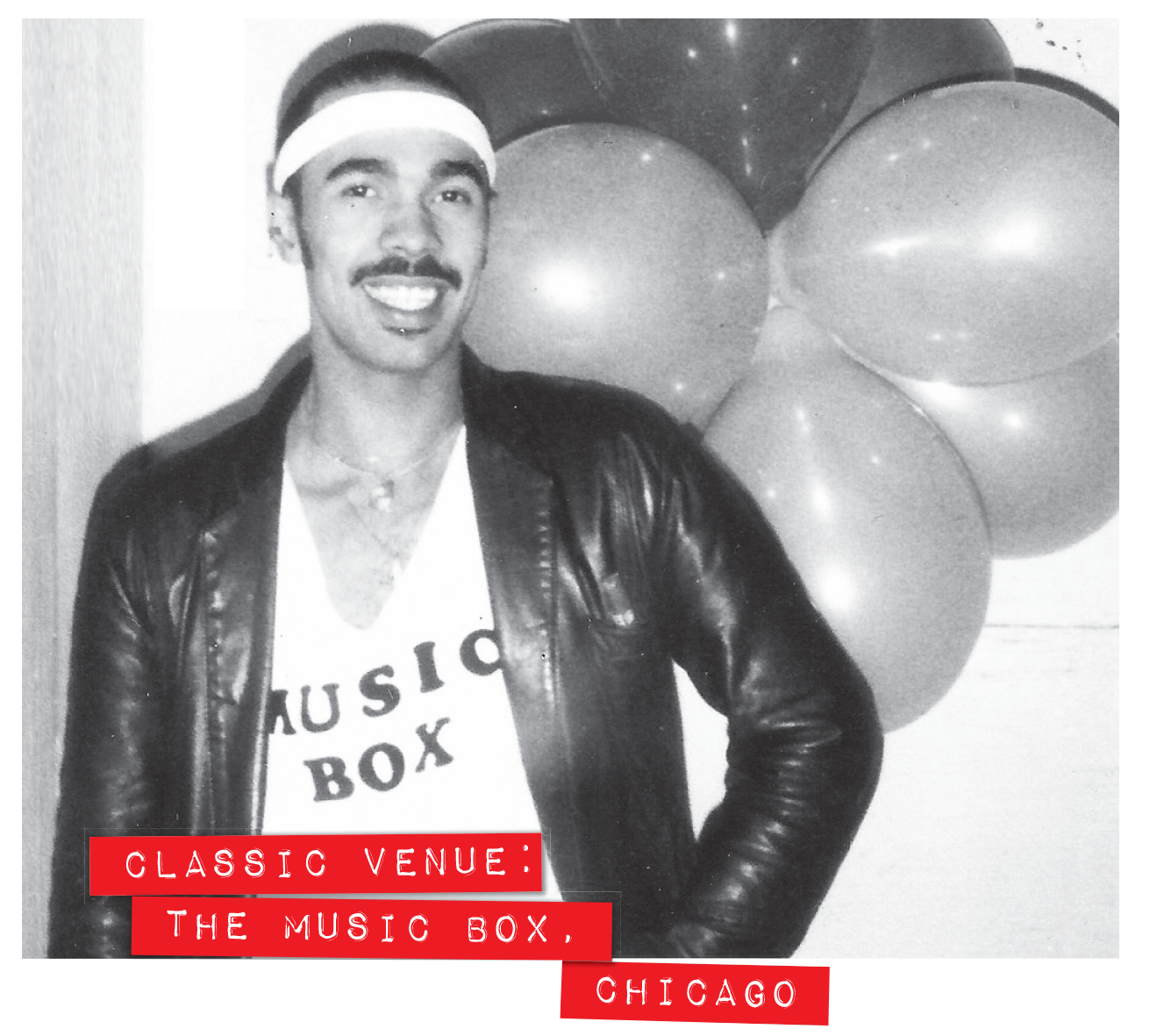

Often obscured beneath the daunting shadow of house music’s birthplace, The Warehouse, the legacy of Chicago’s Music Box (also spelt Muzic Box) is easily missed, not least given The Warehouse (1977-83) and Music Box (1983-87) were in fact the same venue. This all resulted from Frankie Knuckles ending his historic association with The Warehouse to open a rival club, the Power Plant, paving the way for the emergence of a new Chicago force, DJ Ron Hardy.

Hardy, who’d previously DJ’d in both Chicago and LA, had at first declined to take over The Warehouse, but the change of name swung it – he was starting with a fresh slate. As the Chi-town dust settled, Knuckles’ Power Plant on a Friday and Hardy’s Music Box on a Saturday became the biggest weekly club nights for the city’s burgeoning underground dance community.

Eccentric and volatile, Hardy was a true renegade who constantly pushed the boundaries with his experimental, often erratic sound manipulation, championing the acid house direction in the process. His time at the Music Box inspired a whole generation of upcoming producers; Marshall Jefferson, Adonis, Larry Heard, Chip E and DJ Pierre included. What made Ron Hardy so pivotal to Chicago’s house scene was the open, DIY philosophy he applied to presenting music in a club space. Hardy would be known to try out untested tracks handed to him on the night, regardless of who might have brought it up to the booth; something, it’s said, that Knuckles would never dream of doing.

Whilst, generally speaking, Knuckles played records from a more traditional soul and disco background to a predominantly gay crowd, Hardy, whilst retaining the emphasis on black music, played a more eclectic selection to a mixed crowd. Introducing new wave, Italo-disco, and even punk into a house and disco environment, Hardy’s intensified style inspired his young, absorbent audiences, whipping them into such a frenzy that the room would be described as ‘begging for mercy’.

In 1987, Chicago passed laws forcing after-hours clubs to close at the same time as bars, and the Music Box would go out of business as a result. Like his New York contemporary, Larry Levan, Hardy died in 1992, having struggled with heroin addiction for a number of years – he was 33. Unlike Levan, he never got to play in the UK, leading to him being described here as ‘the greatest DJ we never saw’. His legacy lived on however, via the re-edits underground – the reel-to-reel cut-ups he would play at the Music Box proving a key inspiration for the next generation of edit enthusiasts, Theo Parrish and DJ Harvey included. During the mid-00s a number of Hardy edits began to appear on vinyl, some authentic, others tributes by DJs imitating his style.

Whether he was working the EQs, playing a track backwards, pitching up the tempo, or leading his audience down the rabbit hole of a moebius-like loop, Hardy was a maverick – the Music Box offering him the ideal space in which to take risks, unleashing his unique brand of DJ anarchy, and deeply enriching the house music ethos – the Music Box yang to the Warehouse yin.

‘The Tears Of A Clown’ is a titan amongst tunes, first issued in 1967, and co-written by a teenage Stevie Wonder, it’s a once heard never forgotten experience. With lyrics inspired by ‘Pagliacci’, an opera by Italian Ruggero Leoncavallo from the late 1800s, it’s one of the best-known Motown recordings - what might be termed a classic amongst classics.

Yet this wasn’t even issued as a single in ’67, but hidden away as the closing track on an album called ‘Make It Happen’. The Miracles had already had 14 hits in the US chart by this point, the biggest being their first, 1960’s ‘Shop Around’, which peaked at #2, but the label slept on ‘The Tears Of A Clown’ - they obviously didn’t hear this as a hit single, whereas this would subsequently become the group’s biggest hit of all, 3 years down the line.

The key to its success wasn’t in its home country, but across the Atlantic, and acts as a perfect illustration of how UK club DJs have been breaking records in this country since the ‘60s, their obsession with black music bringing soul to the fore during this period; an initial trickle of hits in the early part of the decade, followed by the opening of the floodgates, especially with regards to Tamla Motown, the UK umbrella for the various Berry Gordy owned labels – Motown, V.I.P, Soul, Gordy, Tamla etc. This was topped off by the hugely successful ‘Motown Chartbusters’ compilation series, launched in 1967.

It’s against this background that ‘The Tears Of A Clown’, having been overlooked at source, was picked up on by some British DJs who looked beyond the 7” releases, curious that there might be some hidden gems on the LPs. In 1969, following a quartet of more modest UK hits, Tamla Motown finally got Smokey & The Miracles into the Top 10 with a 4 year old recording, ‘The Tracks Of My Tears’, but were unable to capitalize on this success because Robinson had decided to leave the group to concentrate on his role as vice-president of Motown, as well as raising a family.

His departure halted the momentum, but, the following year, the UK label released another track from the band’s back catalogue, not a former US hit this time, but a relatively obscure album track that had found favour in the clubs called ‘The Tears Of A Clown’.

It was an inspired move, the single topping the UK chart, a feat that would greatly impress the parent company in Detroit, who decided to unleash the track in the US after bringing it up to date sonically with re-recorded drums and bass. It would give the group their first US #1, resulting in Robinson re-joining The Miracles for 2 more years. ‘The Tears Of A Clown’ is now an acknowledged classic, known far and wide – yet it so nearly wasn’t!

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Curtis' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here

Check out the next Discotheque Archives here