GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #6

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

James Hamilton isn’t a name that springs to mind for most people with regards to UK club culture. There’s been an almost total disconnect, commencing even prior to his death in 1996, which has greatly shrouded his legacy.

He started to DJ in his early 20s, playing rhythm & blues in 1963 at Esmerelda’s Barn, a nightclub in London’s Knightsbridge, infamously owned by the Kray Twins.

The following year he headed over to New York to work for Seltaeb, the US company who’d acquired the merchandising rights for The Beatles, becoming a talent scout for their newly formed music division. The combination of his far-back accent, imposing physicality, and deep passion for black music marked him out as a British eccentric who could wax lyrical about records with the best of them.

Having DJ’d at Mitty’s General Store in Water Mill, NY, rubbing shoulders with the likes of James Brown, Sam Cooke and Diana Ross, Hamilton returned to the UK and held a residency at The Scene, the fabled London nightspot, from the summer of ‘65 until its ’66 closure. By this point he’d adopted the DJ name Doctor Soul, and would compile an album with this title for Sue Records. He would subsequently set up as a mobile DJ, and begin writing US reviews for Record Mirror.

However, it was during the following decade, from June 1975 onwards, that he really found his vocation, taking over Record Mirror’s weekly ‘Disco’ column and creating an essential port of call for any self-respecting British DJ.

Perhaps more than anything, he was a champion of New York style mixing, playing music continuously, rather than interjecting between records via the microphone, as was the British way. Hamilton worked on the first UK mix album, 1978’s ‘Instant Replays’, a DJ promo from CBS Records (full album embedded above).

Pushing this new direction in the face of general indifference, he began to make some headway when he started to painstakingly BPM his records, publishing the information in his column. It would be another decade before mixing fully gained the upper hand over the microphone, but it was undoubtedly Hamilton who pushed this process along from its earliest stages.

From the late ‘70s to the early ‘90s he would put together a series of end of year mixes for London’s Capital Radio (the latter with his friend Les Adams). He would also enjoy a long residency at Mayfair club Gullivers.

His record collection, which was said to include over 250,000 items, some with personal notes written on the sleeves, was auctioned off and is now scattered here there and everywhere, dissipated, just as his influence has been.

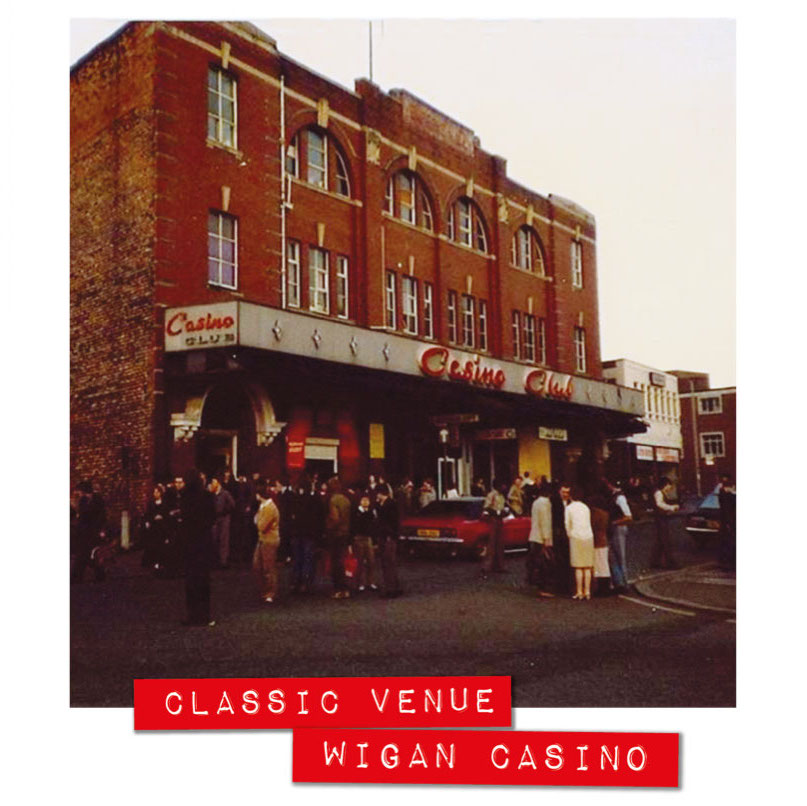

In March 1973, when police pressure caused the closure of the Golden Torch in Stoke-On-Trent due to amphetamine use on the premises, it left a vacuum on the nascent northern soul scene, which had evolved out of mod all-nighters at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s. The Torch took up the baton from the Wheel, but a new venue was needed to usher in the scene’s most celebrated era.

Six months later, The Casino, an old ballroom ideally situated, just off the M6 motorway in Wigan, would fill the void by hosting their own weekly all-nighters from 2am-8am every Saturday. Artists who appeared there included Jackie Wilson, Junior Walker & The All-Stars and Edwin Starr, but it was the DJs, most notably Richard Searling & Russ Winstanley, who were the club’s lifeblood, with the Wigan emphasis being more on uptempo ‘stompers’ to satisfy the frenetic dancers – northern soul’s infamous schism was due to Blackpool Mecca, another crucial venue, featuring contemporary disco tracks as part of their playlist, whilst Wigan kept strictly to the ‘60s soul rarities that had originally defined the movement.

The high water mark for the Casino was 1978, when it was named best club in the world by Billboard magazine, an honour previously bestowed upon New York’s Studio 54. The previous year Tony Palmer had focused on the Casino, for Granada’s TV documentary series This England, bringing cameras into the venue for the one and only time, much to the annoyance of many regulars who objected that the bright lights used for filming spoilt the atmosphere.

The Casino all-nighters traditionally ended with a trio of tracks known as the ‘3 before 8’ - ‘Time Will Pass You By’ by Tobi Legend, ‘Long After Tonight Is All Over’ by Jimmy Radcliffe, and ‘I'm On My Way’ by Dean Parrish. The final great Casino discovery, unearthed by notorious bootlegger Simon Soussan, was the ultra-rare ‘Do I Love You (Indeed I Do)’ by Frank Wilson, originally pressed on Motown’s subsidiary Soul label in 1965, but first played by Winstanley in 1978 as a ‘cover-up’ (artist name changed to Eddie Foster). Only 2 copies of the record are known to exist, one selling in 2009 for £25,000!

With the jazz-funk scene emerging in the late ‘70s, northern soul gradually declined, the Casino closing in 1981. I’d arrived in the town myself in 1980, to take up the residency at Wigan Pier, which had opened the previous year – it’s state-of-the-art American styled approach to sound and lighting in stark contrast to the rundown ballroom surroundings of the Casino - the old giving way to the new.

With one foot in the film industry of LA and the other in the disco scene of New York, Casablanca, founded in 1973, was an essential label of the ‘70s. Set up by the bold and brash former Buddah Records executive Neil Bogart, it would release music from a diverse roster including Donna Summer, Parliament, Kiss, Cameo and the Village People. Casablanca took its name from the 1942 movie classic, a favourite of Bogart’s – who shared his last name with lead actor Humphrey Bogart.

Big successes in 1975 followed a shaky start. After a disappointing run of album releases, rockers Kiss reached the US top 10 for the first time with their concert album, ‘Alive!’, before Donna Summer’s sensually charged single ‘Love To Love You Baby’ provided a major international breakthrough on becoming a global disco hit. An album of the same name featured an epic 17-minute version of ‘Love To Love You Baby’ – specially requested by Bogart – which filled the whole of side one. Its sexual energy led to it to being banned by radio stations on both sides of the Atlantic, but the single reached #2 stateside nonetheless.

Donna Summer was crowned ‘the queen of disco’, taking up the mantle from Gloria Gaynor, and would subsequently stack up a whole heap of hits including the US #1s ‘MacArthur Park’, ‘Hot Stuff’, ‘Bad Girls’ and (with fellow diva Barbara Streisand) ‘No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)’. The producers behind these tracks, Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte, would revolutionize dance music in 1977 via their futuristic electronic masterpiece ‘I Feel Love’, Summer’s most enduring release - a #1 in the UK.

Whilst his band Funkadelic were signed to Westbound Records, George Clinton’s Parliament dropped anchor at Casablanca, their p-funk sound coming into wider consciousness via the platinum selling 1975 LP ‘Mothership Connection’, which built on the groundwork of their previous albums ‘Up For The Down Stroke’ and ‘Chocolate City’.

The Village People, the most popular gay recording artists of the disco era, would secure a major worldwide success in 1978 with ‘Y.M.C.A’, whilst Casablanca further emphasized its disco affiliation that year via the film. ‘Thank God It’s Friday’, an attempt to cash in on the success of the blockbuster disco movie ‘Saturday Night Fever’ (1977), with a soundtrack of mainly Casablanca artists. The critics slated it though, describing the movie as ‘perhaps the worst to have won some kind of Academy Award’ (for Summer’s hit ‘Last Dance’).

Bogart would remain at the helm of Casablanca until 1980. He died of cancer in 1982. The reactivated label is currently part of Universal Music.

During the hybrid early ‘80s there were so many innovative underground records released, with New York’s recording studios overflowing with invention and technological experimentation. The rulebook was literally being rewritten.

When D Train released the François Kevorkian mixed ‘You’re The One For Me’ in late ‘81, we knew things were moving in an exciting new direction (we’d subsequently learn that FK’s inspiration was the cult British track, ‘Love Money’ by T. W. Funk Masters). This pattern was confirmed via other releases, including Northend’s ‘Tee’s Happy’ (produced by the soon to be vaunted Arthur Baker), ‘Time’ by Stone, Electrik Funk’s ‘On A Journey (I Sing The Funk Electric)’ and the mighty ‘Don’t Make Me Wait’ by the Peech Boys, co-produced by Paradise Garage DJ Larry Levan and appearing on vinyl a month or so ahead of the record that would establish Shep Pettibone amongst NYC’s elite remixers - Sinnamon’s ‘Thanks To You’, issued on the Becket label and going on to top the US dance chart, despite only limited mainstream approval.

Producers/songwriters, Eric Matthew (aka Joseph Tucci) and Darryl Payne were a partnership that scored an impressive run of club successes together during ‘82 and ‘83, including tracks for Prelude artists Sharon Redd, France Joli and the aforementioned Electrik Funk. Separately, Matthew would produce club favourites for Toney Lee, Dr Jeckyll & Mr Hyde and Gary’s Gang, the group he co-founded in 1978, scoring major disco hits with ‘Keep On Dancin’, ‘Do It At The Disco’ and ‘Let’s Lovedance Tonight’.

Pettibone, a DJ on New York’s influential dance station Kiss FM, had come to attention via his radio ‘mastermixes’. Following on from the success of ‘Thanks To You’ he’d cement his reputation via the seminal ‘98.7 Kiss FM Mastermixes’ compilation on Prelude, containing new versions of some of the labels biggest tunes of the early ‘80s, all re-edited by Pettibone.

Most DJs on the specialist black music scene in the UK played the excellent vocal mix of ‘Thanks To You’, but, as was often the norm with me, I flipped it over, focusing on the long-building instrumental mix, which went straight into the ‘Fierce Reprise’, bridged by a powerful breakdown, revolving around the track’s essential Peech Boys inspired electronic claps - all in all, a 14-minute marathon of indispensable dancefloor energy, culminating in a climatic dub vocal section. Unfortunately the UK 12” didn’t include this truly epic version, so many non-import buying DJs in this country were completely unaware that such a mix existed. Needless to say, if you’re going to buy a vinyl copy make sure to source the US 12”.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Hamilton' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here

Check out the next Discotheque Archives here