GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #8

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

The role of DJ has historically been male dominated. Whilst sexism is still unfortunately a factor within the industry, the environment is markedly less discriminatory than it once was. It certainly took a special kind of gumption for a female DJ to succeed in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when Anita Sarko took her place amongst New York’s nightlife elite.

Growing up in Detroit in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Sarko came from a pop music loving family - she was always the one to take records to parties. She started out on college radio in 1976, whilst studying music recording at Georgia State University, but it was in the clubs of Manhattan where she really cut loose.

In 1979 she took her place in the VIP room at the Mudd Club, a pivotal venue on the postpunk downtown arts scene, becoming known for her eclectic/don’t give a fuck selections. Her playlist was made up of new wave, no wave, punk, reggae, African, funk and rap, with a definite leaning towards UK recordings, considered exotic/esoteric in NY back then. Sarko would also dig out forgotten curios and was even known to drop in classical and spoken word. She was unashamedly contentious, reacting against audience expectations – she couldn’t care less whether people danced or not. In this respect Sarko was something of an anti-DJ playing to a contrarian audience.

The Mudd closed in 1983, its thunder stolen by Danceteria, another arts-geared venue, opening in 1979, but moving premises in ’82. Sarko became resident at Danceteria in ’83, giving many of NYC’s rising stars a platform, Madonna, the Beastie Boys and performance artist Karen Finley included, via the No Entiendes nights. She also brought in big local and international names like New Order, The Smiths, Run-DMC, LL Cool J and Philip Glass. Elsewhere her weekly sessions at Lotus Blossom Chinese Restaurant, then Club MK, introduced karaoke to America.

In 1985 Studio 54 co-founders Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager invited her to work at their new superclub The Palladium, where the New York Times dubbed her ‘queen of the discotheque deejays’. In the 1990s she DJ’d at fashion shows in New York, Europe and Japan, plus private parties for stars including Prince, Whitney Houston and Cher, whilst contributing music reviews and opinion pieces to magazines like Paper, Egg, Playboy and Interview.

In October 2015, following a successful yet draining struggle with cancer, Sarko sadly took her own life, worried about a future without creatively satisfying work to sustain her. Her early career is celebrated in Tim Lawrence’s recently published ‘Life And Death On The New York Dance Floor 1980-1983’.

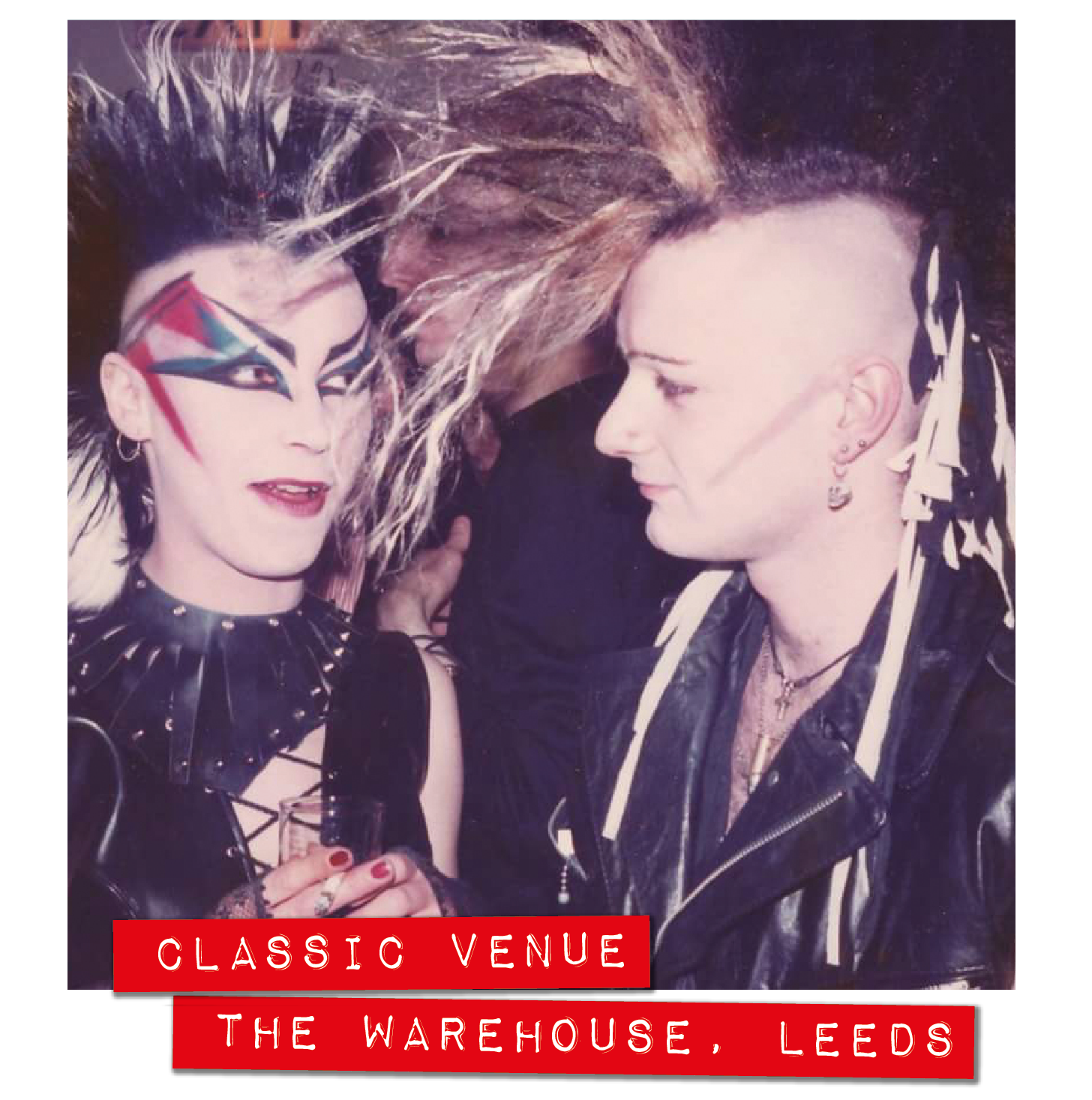

In 1979, Wyoming raised Mike Wiand opened The Warehouse in Leeds with wife Denise. Sound and lighting in UK clubs was then largely basic - DJs revered for their microphone skills, mixing yet to catch on. Inspired by Marbella’s jet-set haunt Regine’s, which boasted a fine sound system/impressive lightshow, The Warehouse bucked this trend, their choice of DJ emphasizing this.

London’s Embassy club, a celebrity hang-out with aspirations of becoming Britain’s Studio 54, had brought over Greg James, an Argentinian born American, and friend of Studio 54 DJ Richie Kaczor, for a 6 month residency in 1978. Vaunted as the UK’s first mixing DJ, James was enticed to The Warehouse by Wiand, initially helping set up the sound system, installed by Yorkshire firm JC Sound Hire.

Continuously mixing the latest NYC disco releases, James provided The Warehouse with a unique attraction. Priding itself on superior sound reproduction, with the emphasis firmly on the DJ, it was the forerunner for a new breed of forward thinking British clubs including Wigan Pier, Camden Palace, Manchester’s Legend and Birmingham’s Powerhouse.

After a year James returned south, later opening the record store Spin Offs. Brooklyn’s Dan ‘Pooch’ Pucciarelli took up the mixing baton, frequently flying over to play The Warehouse throughout the early ‘80s, but it was arguably the Monday DJs, initially Marc Almond and Kris Neat, later Marten Read, who made the biggest impact on the club.

Monday’s Roxy/Bowie sessions incorporated new British electronic releases by the Human League, Ultravox, Tubeway Army, and other Kraftwerk devotees. This futurist direction flourished with the onset of the ‘80s, The Warehouse one of its prime arenas - a magnet for goths and new romantics.

With disco losing its footing as the decade concluded, The Warehouse evolved a more eclectic Monday night inspired music policy. As the ‘80s unfurled, new resident, Ian Dewhirst (previously Northern Soul’s DJ Frank), adopted an open-minded approach, juxtaposing the latest alternative/ indie releases alongside New York’s cutting-edge electro-funk (The Warehouse would even obtain the UK license for the Shannon hit ‘Let The Music Play’).

It was Dewhirst who, having dug out some old Northern classics when blue-eyed soulsters, The Q Tips, were performing live, saw Marc Almond, working that night in the club’s cloakroom, rushing over to the booth to ask what was playing. It was ‘Tainted Love’ by Gloria Jones, a track that Almond’s band, Soft Cell, would swiftly cover, giving them a global hit in the process.

Wiand would eventually sell the venue just as the rave era began to take hold. The Warehouse, very much a Leeds clubbing institution, remains open to this day.

Founded in 1976 by Mel Cheren and Ed Kushins, who’d previously worked together at Scepter Records, New York’s West End became one of the quintessential underground dance labels of the late ‘70s/early ‘80s.

Cheren played a telling role in the evolution of club culture. Towards the end of his time at Scepter pressing the first 12” DJ promo - the 1975 Tom Moulton mixed single ‘(Call Me Your) Anything Man’ by Bobby Moore - whilst in ’77 he helped set up NY’s legendary Paradise Garage, owned by his partner, Michael Brody.

West End’s first single was the jazzy ‘Sessomatto’, by Sesso Matto. A cult release, taken from an Italian film soundtrack, it would find favour on the nascent hip-hop scene for its break, becoming a favourite of cut and scratch innovator Grandmaster Flash and DJ Marley Marl, who remembered it as the first record he attempted to sample.

Key late ‘70s releases included Karen Young’s ‘Hot Shot’ and ‘(Everybody) Get Dancing’ by The Bombers, but the label really hit its stride in the new decade, Loose Joints’ mutant groove ‘Is It All Over My Face?’ setting the tone. Taana Gardner’s ‘Heartbeat’, was a slow burner with a low BPM, initially difficult for club DJs to programme, but thanks to remixer Larry Levan’s persistent plays at the Paradise Garage, plus the support of the city’s roller disco DJs, Danny Krivit included, for whom it was a firm skater favourite, the track ignited in New York.

In 1982, Levan’s would co-write/produce one of the most influential records of the era – the granite hard electronic masterwork ‘Don’t Make Me Wait’ by the Peech Boys, with its fierce claps soon to be much copied, changing the goalposts entirely - dance music morphing into new directions as a consequence.

West End would enjoy a whole array of cutting-edge club hits during the next few years, including ‘Time’ by Stone, Raw Silk’s ‘Do It To The Music’, ‘You Can’t Have Your Cake And Eat It Too’ by B.T (Brenda Taylor), Shirley Lites ‘Heat You Up (Melt You Down)’ and ‘Another Man’ by Barbara Mason.

With AIDS cutting down many of those close to him, Brody included, Cheren began to lose heart, leaving the label in the mid-‘80s following a dispute with Kushins. After winning back control in 2000 he reactivated its back-catalogue, exposing West End to a new generation of DJs.

Mel Cheren died in 2007 - 'The Godfather of Disco', a 2006 documentary based on his autobiography, ‘My Life and the Paradise Garage: Keep On Dancin’ (2000), serving to highlight his integral role in club culture.

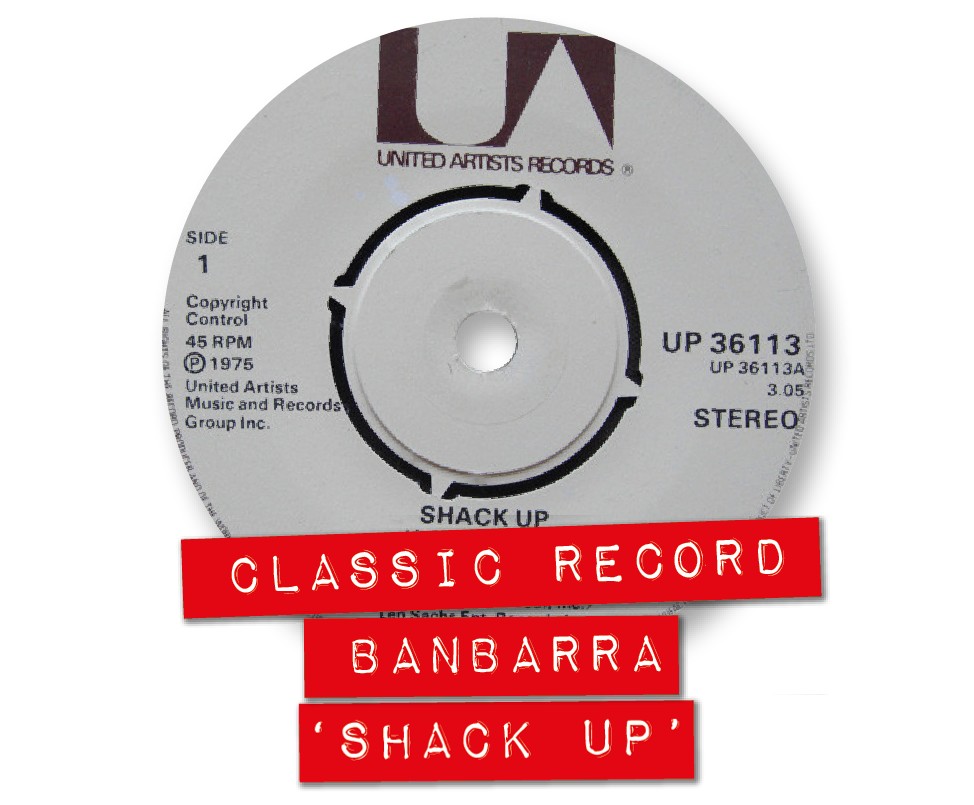

In 1975 a single by a new funk band out of Washington, D.C. appeared on the United Artists label. ‘Shack Up’, flipped with a guitar heavy instrumental ‘Part II’, addressed one of the burning issues of the day – that of co-habiting with a partner outside of marriage, or what was more commonly referred to as ‘living in sin’.

This all sounds pretty tame by today’s standards, but it’s not the subject matter that’s kept this record fresh for over 40 years, it’s the track’s seriously kick ass beats. At the time, it seemed that Banbarra were surely set for big things, but they’d vanish almost without trace, leaving nothing behind but a great get down groove, and wonderings of what might have been.

Appreciated more at the time in the UK clubs than on the US disco scene, the track’s killer break would subsequently find favour with an emerging wave of hip-hop DJs - its legend assured in 1986 when ‘Shack Up (Part II)’ appeared on Volume 5 of the hugely influential ‘Ultimate Breaks And Beats’ series. Over the years many acts, including Public Enemy, De La Soul, Beck, Happy Mondays and Prince have sampled the track.

It’d always puzzled me that there’d never been a follow-up to this remarkable 45. How could someone make such a brilliant record, then never release anything else? It didn’t add up, and I was fascinated to find out what had happened. I’d come to discover that Banbarra never actually existed as a band as such, but was, in essence, a studio project that disintegrated before it had barely started.

Martin Moscrop of Manchester’s A Certain Ratio - who’d covered ‘Shack Up’ in the early ’80s, exposing it to a new audience of indie kids, whilst achieving a highly creditable top 50 placing on the US Dance chart – hooked me up with the track’s publisher. What I’d discover would appear in Wax Poetics magazine as an article titled ‘Banbarra Unmasked’ in 2007.

The single, it transpired, had resulted in an album deal, however, in a case of the same old story, a shifty manager walked off with the cash, collapsing the whole project in the process. Various people connected directly and indirectly with ‘Shack Up’ went on to forge successful careers in the recording industry, but the drummer, John Cannon, the man behind one of the most legendary breaks funk has served up, would fail to gain a foothold, returning to the obscurity of his job with a power company, whilst singer Wesley Aydlett and bassist Steve Moody would also never be heard of again.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Ms. Sarko' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here

Check out the next Discotheque Archives here