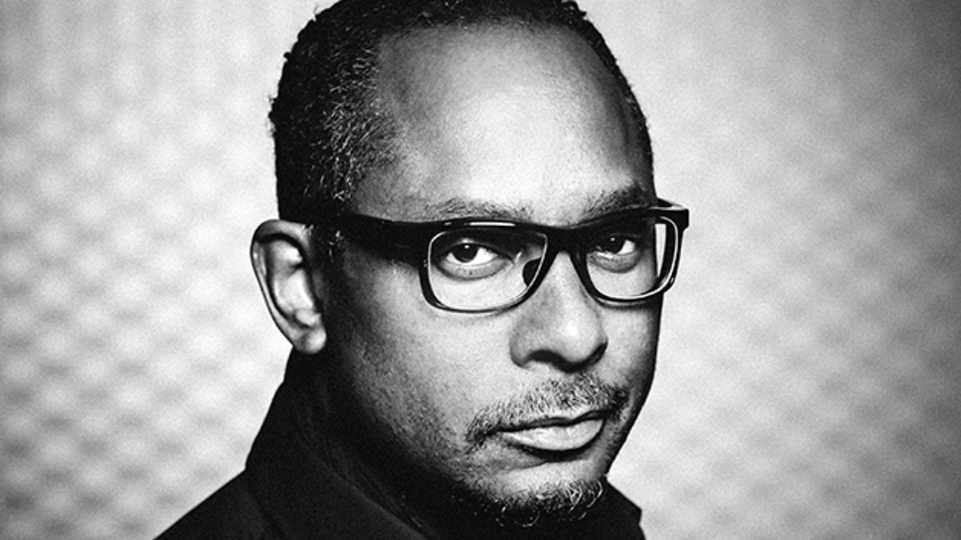

DJ MAG MEETS DERRICK MAY AHEAD OF HIS HACIENDA SHOW

We talk unreleased tunes & future plans with the Detroit legend...

Derrick May needs little introduction. As one of The Belleville Three, alongside Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson, he was instrumental in the birth of Detroit techno, and pushing the limits of early dance music. His reputation as an originator is simply unassailable.

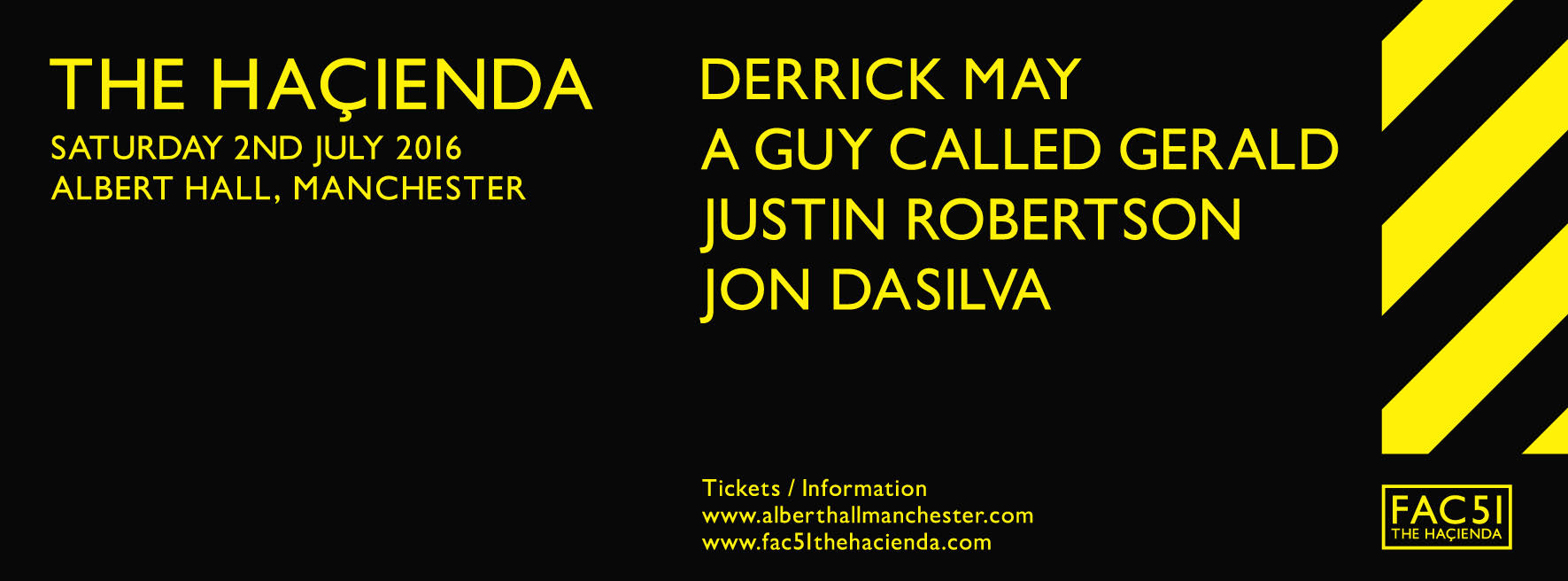

This weekend, he plays The Albert Hall in Manchester at FAC51 The Haçienda, with A Guy Called Gerald, Justin Robertson and Jon Dasilva also on deck. Before taking to the stage, he caught up with DJ Mag to discuss his history of making music, mentoring Carl Craig and how perfectionism can be a gift as much as a burden.

---

You're a proud ambassador for Detroit. Why do you think you're so identified with the city?

"When I started, I spoke with attitude, perspective, anger, frustration and passion for Detroit, so I became the unofficial representative of the electronic music scene in the city. I never wanted that kind of recognition, I just spoke my opinion. It was odd as when journalists asked us about how the music could play a role in Detroit, Kevin and Juan would always look to me to answer the question. My ability to be able to speak and carry myself well with an audience developed from there and became second nature."

You, Kevin and Juan all had studios on Gratiot Avenue in Detroit's Eastern Market where Transmat is still based. Were the early days of Detroit techno incredibly close?

"Yeah. It was known as ‘techno boulevard’. I bought a building on the block and I told Juan and Kevin. The electronic music scene was in full swing in those early days. Chicago was exploding. Other artists in Detroit were making music. Then I took over the Gratiot building with the label in 1988 and Juan also took a place. After that it just kind of exploded. I met Carl Craig the same year when he was just 18-years-old, as well as Jay Denham and Antony “Shake” Shakir. They all became part of the team and it took off."

In addition to Carl Craig, I saw a piece by Stacey Pullen where he talked about the support you gave him as well?

"It was the only way to create a legacy. You cannot continue, fight and create a cause without strength in numbers. Having these excited young minds around that want to learn and make music was really important. These were moments that would shape music. It was amazing to be an integral part of it and to make sure my guys survived it.

"Carl was extremely talented from the start. I put him in the environment to do it but he only needed to the provisions to create music he would go on to make. I watched him and gave him advice but what I also did was slow him down. I had to because I was afraid he was going to be exposed to the kinds of thing that would destroy him. I frustrated him by making him wait. But once he went, he took off and became who he is."

You never seem to like talking about your back catalogue. But what was it that drove you during that period?

"I had a lot to prove to Juan. He never doubted me but did decide when I would be ready, like I did with Carl. Juan was trying to decide that for me. I sort of disappeared for around nine months between the summer of 1986 until the spring of 1987. I'd only made one record and Juan assisted me on it. I was so frustrated because I didnt want him to help but he insisted that I wasn't ready. That was the time of ‘Let's Go’ by X-Ray. I was quite upset with that record because I didn’t think it was me.

"After that I remember Juan’s brother and I had an argument. It wasn’t a big deal. But I looked to Juan as the disagreement was with his brother, Aaron. At this point, they were like brothers to me. I had known them since I was 13-years-old. I don't have any siblings of my own. So these guys were my second family. What happened next would be the telling moment in my young life. When I asked Juan who’s side he was going to take, he told me, ‘Blood is thicker than water’. I was devastated, so picked up my bag and walked out. That moment fired up something up in me."

You've never really been one for talking about the influence of your work, why do you think that is?

"It just happened because of passion. I was alone, didn’t talk to anybody and didn’t have any money. I was just a kid making music and I didn’t care what anybody thought. When I finished making all this music, I think had around 200 songs, but I didn’t have any money to put anything out. I still refused to go back to Juan and ask for help though, as I was trying to prove a point.

"Then Anthony “Shake” Shakir brought Tom Barnett over to my flat. He was just a kid himself, but he had a job working as a security guard in a shop so had a little bit of money and an idea for a record, which became ‘Nude Photo’. He didn’t understand the concept of making electronic music, so just brought the concept for the song. At first it sounded like ‘Blue Monday’. I asked him to let me do something with it overnight. I took the inspiration of what he brought, and when he came back the next day he loved it. We had three hundred dollars to put the record out, with ‘The Dance’ and ‘Move It’ on the flip.

"Before that record was made I’d already produced ‘Strings Of Life’, but I had a hard time with it. In some ways I was scared of it as it was quite extreme. It's hard to get it into words, but I couldn't understand it at the time."

How do you look at your back catalogue now?

To look back on it now is strange. I avoided looking back for several years, deliberately refusing to think about it because I still have a lot further to go. I might do when I retire, but I never want to think that was my best. I want to believe that I can still learn and go further.

You have mentioned that you have bundles of unreleased material. Is it perfectionism that stops you putting it out?

"You're right on cue. I became my own worst enemy because I never thought it was good enough. I was my worst critic and spent a lot of energy being a mentor. I didn’t realise how much time goes to helping younger artists. I surrounded myself with all these young people in my studio and it became exhausting. It was impossible to be a mentor and also hold onto that creative part of yourself at the same time. So I fell back on my DJ skills the moment these artists took wings and were able to fly.

"That's why, as happy as I was for Carl’s success, I begged him not to get into the DJ thing as I knew it would become a distraction. He hasn't made music as he did since he started it. I hate the fact that all my guys are doing the DJ thing now. It distracted me and it's distracting them. I made a lot of people money, but I stopped doing it for myself and I regret that now."

Do you think you could return to making new music?

"Yes. I've been working on a lot of ideas. Things are very exciting, but I'm never going to be what I once was. I don't need to be. I want to graduate into another individual with a different expression."

---

You can see more information about FAC51 The Haçienda at The Albert Hall in Manchester below, and buy tickets here.