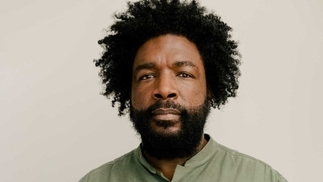

Akala: "As artists our job is to critique"

Akala's Natives: Race And Class In The Ruins Of Empire is a fiercely honest appraisal of growing up poor and mixed race in broken Britain. This heartfelt polemic fights every excuse of racial ignorance and serves as a two-fingered salute of threatening intellect. DJ Mag catch up with the MC, writer, poet and political commentator...

MC Akala, the stone cold power-fisted slayer of Charlie Sloth’s Fire In The Booth freestyle session, can also take down any quasi-righteous, over-privileged member of the establishment on Question Time or Newsnight. DJ Mag’s OFF THE FLOOR worked on setting up this interview with him for a year, after seeing him outshine everyone at Grinagog Festival, and selling out Brixton Academy, smashing Shepherd’s Bush Empire, and taking over Saturday night on the BBC talking about Homer (not the yellow cartoon character). We finally caught up in his exceptionally well-shelved, Grenfell-shadowed music studio. Wearing camouflage sweats and dreads up from spectacular cheekbones, he swizzels, boylike, on the grand producer’s chair: less of a headmaster, more the brightest, most charmingly argumentative kid in the class of 2018.

“The whole of society tells you being smart is for posh people,” Akala says. “I wanted to be an astronaut, I was a geek. And I got encouragement to pursue geekdom, even from my uncles, the ones who robbed banks. I knew I wasn’t born into a meritocracy, my parents taught me that — to suck it up, work harder.”

And he has. His masterpiece, Natives: Race And Class In The Ruins Of Empire has just stormed the Sunday Times Bestseller list, and it’s partly why this interview has taken a while to set up. The book comes as a fabulous two-fingered salute of threatening intelligence. There’s never been a more honest appraisal of growing up poor and mixed race in broken Britain. This heartfelt polemic fights every excuse of racial ignorance, and is no road to riches autobiography. But superficially, having the elder sister of Ms. Dynamite must have helped, on the surface, just a little bit?

“Eighteen months before ‘Boom’ came out, she was living in a hostel, that’s how fast it happened, the transformation,” Akala – real name Kingslee James Daley – says. “She helped me start a record label, so there’s no doubt my sister helped change the possibilities for the family. She became really successful after I’d left school, she was on pirate radio in our local area. I’d become a bit of a naughty boy, we were on the periphery of being rude boys — two of us were into criminal activity, but me and Niomi were making music since we were seven or eight-years-old. The first time I went to the studio I was four, dropped a dubplate for my uncle in my little baby voice, and the first song I recorded, I was probably 14 or 15, so we always wanted to be musicians. Kids think they can become millionaires from music, and they don’t know how new that is.”

But it wasn’t just the family connections of having a stepfather working at Hackney Empire, and a phenomenal mother. Akala played football for West Ham as a teen: “Being good at football is major kudos at school.” And being 6ft at 12 does something for your confidence. Born Kingslee James Daley, he praises having a two-tone education — an Afro-Caribbean weekend school gave him ballast lost in the racism of having mainstream teachers making assumptions, putting him into the Special Educational Needs category early on.

He tells of dossing about in college: “I’m not so judgemental of people who have done bad things in their past, because imagine, one of those times when I was carrying a knife as a kid, or my best friend stole his dad’s gun from under the mattress, if we’d have got arrested and gone to prison, how differently the rest of my life would have gone: Feltham for three years, maybe you have to protect yourself there, you stab up two kids in Feltham, your whole life trajectory, you become an entirely different person. So I don’t believe in my own moral purity: I was very lucky, and part of my luck in life has hopefully allowed me to grow into being a better person. That doesn’t mean I’m inherently a good person: the danger, if we believe in our own inherent goodness, is we believe there are inherently bad people. If only the world was so simple.”

"Humans are fragile and can do fucked up shit. I have a right to criticise my government without being imprisoned or tortured, to me that is free speech"

Labelling gets us all in trouble. Akala tells stories of himself and doctor mates getting pulled for driving nice cars as critical anecdotes, and explores the systems of profiteering policing, and shoddy media that prays on poverty and fuels systemic racism. His book stands up to educational bigotry, and outlines how the state benefits from purposeful denial and oppression of post-Windrush power. “Obviously I enjoy not being in the financial situation I was in growing up, but does that mean I need to have £10 million quid? No!”

So the premise of the book is what exactly? “This sense that we [in Britain] are special and better than everyone else is rooted in the legacy of empire. I wanted to see how that shaped me. I’m not going to lie and say this book is going to resonate with all young working class black boys, but the human experience should relate. I don’t watch Lord Of The Rings and think I can’t relate to Gandalf because I’m not an old white guy. If you come to my music shows, you see I have a disparate audience, it reflects London. Art should transcend.”

The misfortune is, Natives may not reach kids living the first hand experience of discrimination, so that they may learn from Akala’s game of survival. It’s the same play he’s used to get into schools, creating his financial autonomy using Shakespeare as an exemplar of hip-hop in workshops. His comprehension of street apartheid leads him to floor-destroying debates, which lay out a truth that has taken him to lecture at Oxford Union at the famous university. He’s setting up his own production company, which builds on playwrighting, graphic novels, and recording five albums, two EPs and three mixtapes. Is he going to get into politics next?

“I am in politics,” he says. “As an artist our job is to critique, and as someone who does educational stuff with young people. It’s such a dirty, snaky game — I don’t know, if I were to get into number 10, the world wouldn’t suddenly become this wonderful utopia where I’d make all the right decisions, and there’d never be any wars, and everything would be fixed. No one person has that power, and so I’ve always wanted young people to do better in school, while I recognise that the education system is designed to reproduce a lot of the inequalities that already exist. You press the right buttons long enough and hard enough, and bakers and postmen and milkmen can end up putting people in gas chambers. They didn’t suddenly become worse people in the 1930s, the right buttons were pushed. Humans are fragile and can do fucked up shit. I have a right to criticise my government without being imprisoned or tortured, to me that is free speech.”

Do you get people saying you’re too mainstream?

“If I’m on YouTube, no one believes that I’m endorsing Google as an organisation, but if I go on the BBC, it’s like, ‘Oooowah, you’re on the BBC’. Your silence won’t save you, but I’m not reckless, and I try to be calculating. That’s the game. It’s risk versus rewards. I believe states do lie to their people, the Windrush scandal being an example of this, if they said: ‘We’re just going to deport all these old black people’, people would have been aware of it from the beginning, so they find all these loopholes, not calling it what it is, but when you look at this country’s history of immigration policy, it’s been going on since 1948.”

Who stands for WOKE for you right now?

“I was really impressed with Stormzy at a peak moment of his career taking the prime minister to task. The backlash was interesting: ‘Shouldn’t he be grateful?’ You’re supposed to be grateful, because the Daily Mail says he should be grateful because he’s from Ghana. ‘You’re not British, shut your mouth...’ I listen back to reggae music now and I can’t believe that Bob Marley was a pop star.”

And that’s the problem with the rhetoric of our times, that it is so judgemental, it’s them and us, it’s you’re with us, or you’re without. You don’t go into drugs in your book.

“I do think the criminalisation of drugs serves very specific social outcomes. We all know rich kids take drugs and are never going to be choke-slammed on the floor, they’re never going to have their house raided, or be battered by the police, so drugs being illegal can be a great form of social control and a way of controlling people, whether that’s kids selling drugs in east Glasgow, or kids selling crack in east London. The state shouldn’t be able to tell people what they can and can’t put in their body. There’s 40 million weed users, and not a single overdose yet. The whole argument falls apart. I think legalisation and regulation would be the way to go, but my problem, as a British Jamaican, is that the Americans bullied Jamaica into burning down the farms as part of the War On Drugs, essentially ruining its own ganja industry. So now places like California or Israel are far ahead of us, whereas we have the ultimate brand. If there was any one country positioned to sell weed to the world, it was Jamaica, so I feel sad, as it’s an industry that could pull lots of Jamaicans out of poverty.”

On his success, he likes the shelter of not always being recognised, but says: “Criticism and praise are difficult if you let them get to you too much. There’s a Chinese philosophy book, The Tao Of The I Ching — it’s the closest thing I have to a Bible, and one of the things it talks about is not being affected by good or bad. I’m not Buddha, but I try to be unaffected by loss or gain.”

Finally, some words on your process of writing?

“I have two different processes. If I’m writing something that’s like a poem, and I want it to read like a poem, I will put it on the page, to see how it looks, but all four of my Fire In The Booths, not a single word of that ever went on paper. I have the beat on, and I’m writing to the beat, so when you’re in that process, you’re excited, and you don’t want to note down the whole line, note down the last word only. The rhythm really helps, and the beat. And a lot of word association. Takes a while, but if you look at the way I write, you’ll see that there is continuity, I don’t just jump from subject to subject, and that helps.”

If you want to join MC AKALA on one subject, join him in Natives: Race And Class In The Ruins Of Empire — out now on Two Roads.