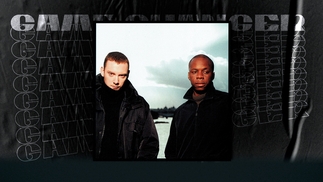

Game Changer: Black Box 'Ride On Time'

As Black Box re-release the original version of their 1989 mega-hit, DJ Mag talks to Daniele Davoli about the birth of Italo house, the dispute over Loleatta Holloway’s vocal and that lip-synced video...

IT’S often said that behind every hit, there’s a lawsuit. Black Box’s ‘Ride On Time’ is no exception. Loleatta Holoway slammed it for ripping off her vocal and was understandably outraged when her voice was then mimed on the video by Katrin Quinol: a non-singing French model.

Despite being the biggest selling song of 1989, topping the UK charts for six weeks, featuring in numerous ads and with nine million Spotify plays, ‘Ride On Time’’s achievements have always been overshadowed by Holloway’s indignation. But as he starts to explain the track’s history, DJ and Black Box founder Daniel Divoli shows genuine sympathy.

“Loleatta was right to complain,” he says.

Black Box’s story begins with the birth of Italo house in the late ’80s, while Balearic in uences were sweeping across UK club culture, and Italians were building their own scene in Rimini. “Ibiza had a strong Italian following in the mid-’80s,” says Daniele. “You’d find Spanish and Germans, but it was mostly Italians — gay people and fashion designers. But Ibiza was expensive, so Rimini offered Italian workers a similar vibe, and Ibiza got increasingly deserted by the Italians after ’87.”

A new sub genre began combining Italian sensibilities with the new music coming from Chicago and the UK. Daniele was among the DJs pioneering the scene, and he became resident at Bologna’s Starlight club.

A large commercial venue, it restricted what he played most nights, apart from at a weekly student club event. “On Thursdays I could play my own thing. The students would go mad, because it was they only place they could hear what they wanted.” Gradually his sound began to take over. “By 1988 every night became 80 percent house. It was more than a new sound, it was a culture. People were carrying whistles or whatever they could to make some noise on the dance oor.” Daniele began honing his sets to work the new scene. “People got excited about anything with a piano. There were records from the US and UK, but they weren’t quite as ‘happy’ as Italians liked it. We needed to give the crowd what they wanted. That’s what defined Italian house.”

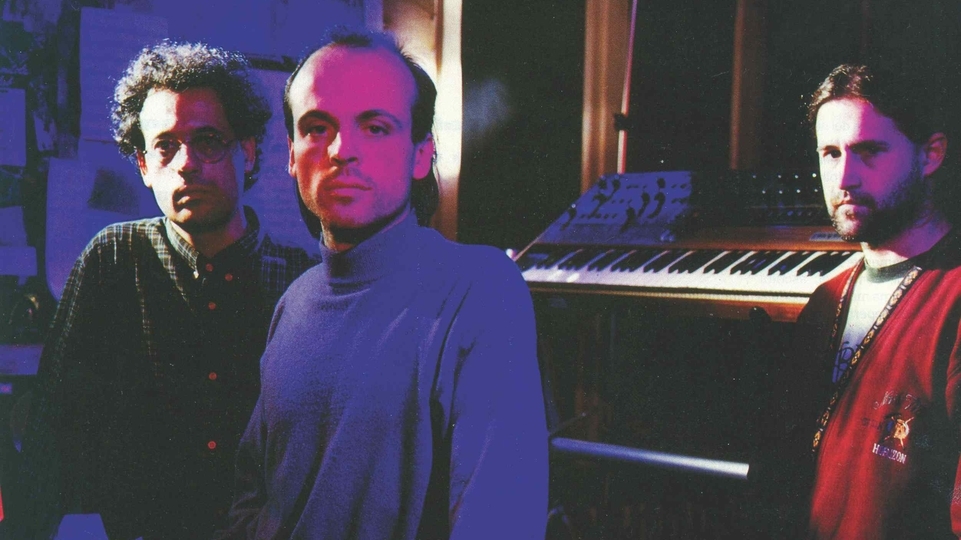

In 1987 Daniele was invited to a friend’s studio to record the early Italo house track ‘House Machine’, by DJ Lelewel. “It was inspired by ‘Pump Up The Volume’, but with a piano. It did well, so they asked for a follow up. I had the idea for ‘Numero Uno’, and I wanted piano. They called this musician, which is how I met [Black Box member] Mirko Limoni.” The studio wasn’t convinced by the track, and cancelled the session, but while leaving, Mirko offered to nish ‘Numero Uno’ at the home studio he’d set up with [third Black Box member] Valerio Semplici.

Completing the track, they began looking for a label. The first to show interest was Severo Lombardoni’s Italo disco label, Discomagic. “They took it on and sold 1,500 vinyl copies, which back then was quite slow... but the label asked for more.”

Taking a few days off, Daniele went to New York and returned with a 12-inch acapella of ‘Love Sensation’. He’d bought it for vinyl mash-ups, but back in Italy he was introduced to samplers. “Mirko announced: ‘I’ve either got to buy a new car or a sampler’. So we got an S900 for the studio. Then I wanted one in the club, so I convinced them to buy one. “‘Ride On Time’ was originally programmed on the club sampler. I sampled a piano line and groove. But there was very little memory. It only fitted three vocal snippets. So I had to play them over and over.”

One night Mirko visited the club, and the next day asked about the track. “I had the floppy disc in my bag, so we loaded it and he said, ‘That’s it!’” Mirko added new piano chords to the chopped up vocal. “In a day we’d put together the chorus and groove.” After adding more vocal excerpts, Daniele took the track out for a road test. “It was heartbreaking. The floor had 1,000 people dancing, and it cleared it. I went back to the studio and told the guys, but they said: ‘It’s just the wrong club’.”

Their confidence was well founded, and shortly afterwards, two visiting British DJs gobbled up the early Italian pressings. “I spoke to Paul Oakenfold, and he said he and Danny Rampling heard Alfredo playing Italian stuff in Ibiza. So they went to Rimini.” Hunting for new Italo house records, they heard ‘Ride On Time’ in a record shop, and asked how many copies they had. After being told there were 20 in the shop and another 20 in stock, they asked if they could get more from the distributor. “I got to know later they absorbed all the copies that were around and brought them back to England.”

In the meantime, UK label Deconstruction had telephoned Discomagic to try and license ‘Numero Uno’. “It had already been signed to Beggars Banquet, so they asked us if we had anything else. We sent a white label of ‘Ride On Time’.” Deconstruction signed the track immediately, but soon found themselves competing against the imports ooding the UK’s specialist shops. “They released it without any press or promotion, and we got called to do Top Of The Pops when they hadn’t even given us a release date,” recalls Daniele.

Propelled by demand for the import, the UK release shot straight to No.1, but its success brought an unexpected problem. “We’d read that if you don’t sample more that two seconds it was alright. But Deconstruction said: ‘We’ve got to clear it’, and got in touch with [‘Love Sensation’’s original record label] Salsoul, who agreed a $5,000 fee. Then [songwriter] Dan Hartman contacted us and was a true gentleman, saying: ‘I don’t want to spoil your moment, give me a third’. We were like, ‘A third’s a big chunk’. But he said, ‘It’s fair, please take it’. Later we discovered he could’ve taken 100 percent.”

But Salsoul’s deal turned out to be trickier. “We were about to go on TOTP, when BMG called and said, ‘Salsoul say we don’t have clearance’.

We said, ‘But you cleared it?’ And BMG said, ‘Salsoul’s contracts had never been returned’.” BMG had paid the agreed $5,000 fee, but Salsoul now said it was only an advance. “The negotiations got nasty,” recalls Daniele. Faced with copyright issues, BMG asked Black Box to record a new vocal, and within a week they’d re-released a new version and withdrawn Holloway’s. The new release went on to outsell every other dance release that year. But this did little to dispel Holloway’s grievances and, although BMG and Salsoul eventually reached an agreement, she apparently knew nothing about it.

“She never saw a penny,” says Daniele regretfully. “The master was owned by Salsoul, so BMG had to pay Salsoul. It wasn’t for us to pay her.” With hindsight, he regrets Katrin miming to Loleatta’s vocal. “It was wrong. But in Italy, a lot of people used to sing on a record and labels would ask young people to become the image. I know ignorance is no excuse, but I learnt. We looked at American and English artists and realised they don’t do that.”

Following many attempts over the last three decades, Black Box have finally been granted the rights to re-release the original Holloway version, but sadly too late for Loleatta, who died in 2011.

“The new BMG bought the Salsoul catalogue, so we asked them if they’d give us clearance. We have always wanted to come clear with the original version. We’re also releasing a ‘Best Of’ album that includes some of the old material that’s been re-mastered, and a brand new track with Celestine, a vocalist we met a few years ago. It’s called ‘Everyone Will Follow’, and we hope everyone will follow... otherwise I’ll open a wine bar and you’ll never hear from me again,” he laughs.