Meet the people creating the Code of Conduct to end sexual harassment in dance music

Sexual harassment is a widespread problem that remains prevalent in our supposedly progressive dance music scene. A number of new initiatives have proposed a solution: a Code Of Conduct to combat abusive behaviour on the dancefloor and in the workplace. DJ Mag spoke to key figures from the project and a number of other companies taking steps towards positive change...

Words: CHANDLER SHORTLIDGE

Pics: HEATHER STEN, SARAH KOURY, BARRON, CLAIBORNE & MICHEAL BREYER

In the year since the #MeToo movement, those who were previously unaware have, at last, been waking up to the horrifying pervasiveness of sexual harassment. It primarily affects women, and is almost always perpetrated by men. It happens more often in public than in private, but is often more violent behind closed doors. It can have damaging effects on victims, who sometimes suffer from anxiety and depression long after the incident is over. And sometimes victims feel forced to alter their lives to avoid further harassment: moving cities, changing jobs, or in the case of some women in electronic music, never setting foot on the dancefloor again.

“I don’t go on dancefloors anymore, because every time I have, I don’t just get touched, I get grabbed,” female:pressure member and synthwave artist Meg Wilhoite (Death Of Codes) says.

Three-quarters of young people in the UK say they’ve witnessed sexual harassment on a night out, according to a 2017 YouGov poll. And half of women polled told the BBC they’d been sexually harassed at work, with a majority never reporting it.

The problem of reporting is even more acute among men: 79 per cent of male victims kept workplace harassment to themselves. And while reasons for not reporting vary between victims, Wilhoite’s own experience (she was harassed by another employee while working at a medium-sized publishing house) offers some clarity. “The process with HR was really awful, and involved telling the guy who harassed me,” she says. “I was so worried about retaliation. Telling the guy was basically putting a target on my back, and I’m never ever going to feel comfortable around this person again.”

When she initially told her boss about it, Wilhoite says she wasn’t seeking to report, “because that’s just what happens when you’re a woman, you get sexually harassed”. But her concerns were overruled by company policy. “HR is there to cover the company’s arse, so they don’t really care about me.” It was a painful process, one Wilhoite understandably isn’t eager to repeat and one nobody should be forced to endure. But sexual harassers rely on women remaining silent. It’s how terrorisers such as Harvey Weinstein managed to abuse dozens of women over dozens of years, and why the men who hurt women, such as those women DJ Mag interviewed in February of this year for the Taking Liberties piece, continually get away with their actions. And just days after Jackmaster admitted to “abusive” and “inappropriate” behaviour towards a female staff member at Love Saves The Day festival, DJ Rebekah tweeted about the continued pervasiveness of sexual assault in the industry at the hands of DJs and promoters.

“I wish a news media would finally report on the cases of sexual assault and rape that has been going on to girls for decades by DJs and promoters,” she wrote. “Yes it’s happened and still happening. And as a female [I] would like to create a safer environment for young women in the scene.”

Carly Wilford

IMMATURITY

This issue was central to the 2018 International Music Summit (IMS) in Ibiza, and the summit’s Sexual Harassment In DJ Culture panel, where industry leaders and artists such as Honey Dijon, B.Traits and SISTER Collective’s Carly Wilford debated the challenges associated with putting an end to harassment in the workplace and on the dancefloor. Panelists discussed the “immaturity” of the industry, which still operates largely without ethical oversight. A sexual harassment Code Of Conduct was suggested, one that could be written right into contracts and would, as B.Traits pointed out, “break down what’s acceptable” behaviour and what’s not. As another panellist noted, this was exactly the idea behind the sexual harassment Code Of Conduct crafted by the We Have Voice Collective.

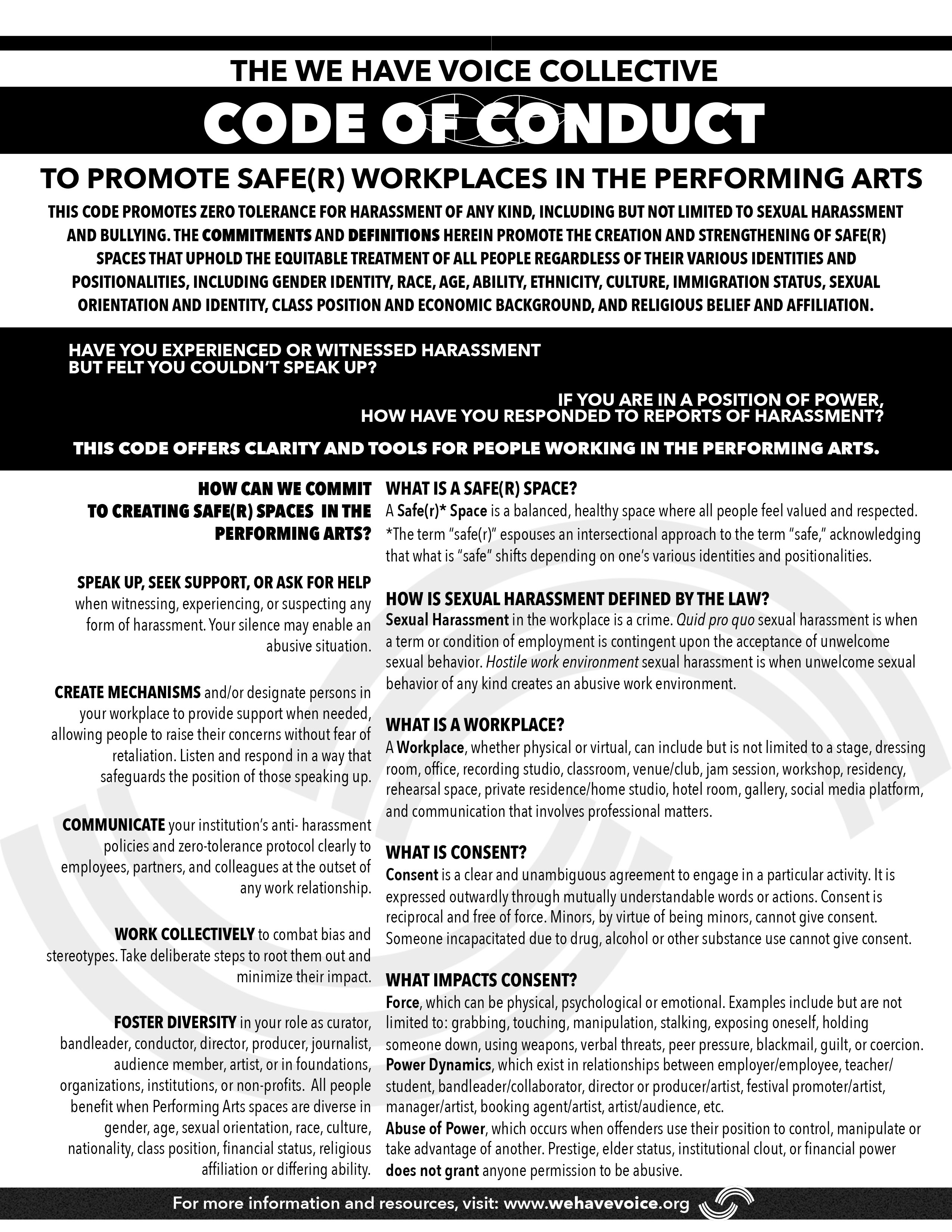

Made up of 14 female and non-binary musicians, performers, scholars and thinkers from different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds who work primarily in jazz, We Have Voice made headlines earlier this year when it released its Code Of Conduct in the wake of that industry’s #MeToo movement. But its creators say the Code isn’t explicitly for the jazz industry, or even music. “The creation of the Code Of Conduct is to provide a standard list of ways to hold those accountable in the performing arts, venues, arts education programmes, festivals and universities,” We Have Voice (WHV) member Tia Fuller says.

Despite its short length, crafting the one-page Code was a strenuous, months-long process that involved: “exchanging thousands of emails, getting together on dozens of Google Hangouts and, where possible, a few in-person meetings to produce the final document,” Tamar Sella says. Rather than a list of “dos and don’ts,” the collective wanted the Code to offer clear definitions with easy-to-understand language around sexual harassment topics in the performing arts workplace, “so that we can find clarity and speak to one another using thoughtful, informed, and respectful language about our lived realities,” Sella continues.

The Code provides concise answers to questions such as “what is a safe(r) space?”, “what is consent?”, and “how is sexual harassment defined by the law?” It offers clear advice on how to “create safe(r) spaces in the performing arts,” with instructional language on topics such as fostering diversity and seeking support if harassment is witnessed. It also advises workplaces to communicate anti-harassment policies to new employees early on. Once the Code was finalised, they asked lawyers and other professionals working in the jazz community outside of their collective for feedback, some of which was incorporated into the one-page document. “It was important that the Code be a dynamic one-page document that could be included in riders and hung on walls of venues,” Sella says.

Christina Wheeler

Christina Wheeler

CODE WORDS

Posting the Code Of Conduct on dancefloors everywhere is something the members of female:pressure support. And at least one member of the female, transgender and non-binary electronic musician network says they’ve already seen it happen, though with a Code Of Conduct written locally, not by WHV. “I’ve been to venues where they have Codes Of Conduct posted,” multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Christina Wheeler says, citing Berlin’s ://about blank and Ableton’s Loop Summit as examples. “But this is definitely not always the case, and I would not presume that the smaller, progressive community I’m in in Berlin is necessarily manifesting in other parts of the world or the larger community in general.”

Wheeler also says that in venues that do have a Code posted, patrons are advised to seek out staff members with a specific code-word if someone is being harassed. “I’ve been to a venue where they said, ‘if you’re having an issue, go to one of the bartenders and tell them this word’, because for someone who’s in this situation, they may be frightened that someone’s really going to do some harm.” Panellists at IMS also brought this up, noting that when specially trained staff responded to code-words, they usually do so in a discreet manner that keeps people safe and doesn’t affect the dancefloor’s vibe — a win for both clubbers and club owners. Beyond code-words, the female:pressure members DJ Mag spoke to believe posting a Code Of Conduct on dancefloors everywhere will provide a level of guidance that has been previously missing from the wider conversation.

“I feel like Codes Of Conduct are important, because they’re a signal that says grabbing someone on the dancefloor or using your power over someone to make them do things for you is wrong, and that is still a thing we have to say,” Meg Wilhoite says. “We can’t just assume that everyone acknowledges that that’s wrong. I think there are lots of people out there — especially men — who think this is still okay. Like, ‘if I’m in a position of power, it’s my right.’ This is why you have to have this conversation.”

Female:pressure emphasise that everyone should have the right to be able to go to a nightclub — or anywhere, for that matter — without being harassed. And so they support implementing the Code beyond dancefloors and into industry-wide workspaces. “The WHV Code is general enough that any space or company could use it because they define everything,” Wilhoite says. “There’s really nothing you can add other than how will you then deal with a violation? This is essentially my company’s Code Of Conduct, but more explicit, better.”

“But as far as I’m concerned, everyone is responsible for their behaviour no matter what condition they’re in, and everyone deserves to be in a space where they’re safe” - CHRISTINA WHEELER

RESPONSIBILITY

As many who make a living in the industry know, the dancefloor is also often a place of work. And proponents of Code-adoption point to the blurred lines that sometimes come with conducting business in an often- hedonistic clubbing environment.

“A lot of business is done in clubs when people have been drinking,” Carly Wilford says. “Our scene has grown so quickly and the lines between work and partying are very blurred, and sometimes people forget that — when they’re playing, they’re actually working,” she continues. With this in mind, the WHV Code Of Conduct clearly defines what a workplace is, describing it in essence as anywhere work is being done, “physical or virtual”. Proponents argue that adopting the Code industry-wide would add a much-needed measure of personal responsibility and professionalism to the scene, pushing back against “traditional” ideas about what’s allowed when work and play commingle.

“One thing that becomes challenging when it comes to spaces where people are in dance music environments, is there’s this traditional idea that, oh, it’s a hedonistic environment, so people are messed up because they do things when they’re wasted, it’s part of [it],” female:pressure’s Christina Wheeler says. “But as far as I’m concerned, everyone is responsible for their behaviour no matter what condition they’re in, and everyone deserves to be in a space where they’re safe.” Keeping people safe requires a greater measure of self- policing than currently exists. And advocates for the Code believe adopting one would serve as a personal-responsibility instruction manual of sorts, listing in black and white what’s okay and what’s not. “There are a bunch of people in our midst who don’t know how to act like decent human beings,” Wilhoite says. “We need to write instructions about how to be a decent human being. This is how you do it. You don’t control people. You don’t touch people who don’t want to be touched. These are things that should be a given if you’re a decent, responsible adult. Unfortunately there are a lot of people out there who are not.”

The more people who act with decency, female:pressure founder Susanne Kirchmayr (Electric Indigo) believes, “then the other ones around are likely to behave well as well,” she says. This also means saying something if you see something, either in the workplace or on a night out. “Part of the Code Of Conduct that’s important is, say you’re a guy and you’re around other guys who are harassing another woman, saying, ‘this is not okay, you gotta stop this,’” Christina Wheeler says. Because the rules are so clearly stated, self- policing will, in theory, become easier. So will reporting and prosecution.

“It means there’s a trail,” Wilford says. “If something happens to you, it means legally you can report it. There’s something to come back on. At the moment, it’s very much ‘he said, she said’. There’s no formal way to insure this behaviour is stamped out.” This was very much behind the thinking of the We Have Voice Collective when they wrote the document. Linda Oh calls the Code an “added pillar of support,” saying it has encouraged her to speak out in situations where in the past she would have remained silent, perhaps brushing off inappropriate behaviour as “something you just have to put up with”.

“This code is a reminder for me that I’m not alone,” she says. “There is a reason we have to have it in place, and speaking out is helping to change the overall culture of discrimination.”

Electric Indigo

INSPIRING

At the time of writing, the We Have Voice Code Of Conduct has been adopted by 46 (non-electronic music) institutions, including festivals, venues, educational institutions, labels and media outlets. Members of the collective say the response has so far been positive, at least anecdotally. “A colleague of mine wrote to me saying how much she appreciated the Code and that it was much needed in her field, being in the technical side of the arts,” Linda Oh says. “The institution she works for has adopted the Code, and many of the staff advocated for it to be posted in the walls of bathrooms where victims of harassment often go to seek refuge, which I thought was a fantastic idea.”

In electronic music, some larger companies already have a Code Of Conduct in place, outlining policies regarding sexual harassment, discrimination, and diversity hiring and retainment. Or like Berlin-based music technology company Native Instruments, all of the above. Regarding sexual harassment, its Code states in-part that, “All employees are... obliged to refrain from harassment, in particular sexual harassment,” which it partially defines as “any behaviour that may, even if only potentially, be viewed as undesirable by the person concerned”. The company also says that while it feels its Code Of Conduct is “very strong,” and more importantly “ingrained in Native’s DNA rather than just lip service,” it would embrace a Code Of Conduct that was distributed industry-wide.

“Having a clear position formulated in a united statement that everyone can commit to is helpful,” Native Instruments’ Head Of People Laura Moreno says. “It has at least symbolic value, [which] probably helps keep a vital discussion alive, and ideally inspires people to act consciously.”

While Native Instruments is similar in its sexual harassment policies to the We Have Voice Code Of Conduct, the tech company covers more ground in its language regarding diversity. It holds an Equal Opportunity hiring policy, and Moreno says the company strongly believes in a “diverse perspective and skill base”. The company also regularly hosts diversity recruitment and awareness initiatives, such as Female In Tech events, and “monthly diversity lunches” hosted by speakers from inside and outside the company to exchange ideas on the issue.

Those policies and initiatives have resulted in employment of over 40 nationalities from every continent at Native Instruments in 2018, an increase of 43 per cent from 2016. “We’re employing all age ranges, including one retiree, and also disabled people,” Moreno says. “Typical to our industry, our female ratio is rather low,” she concedes: women only represented around 17 per cent of the technology workforce in 2017 in the UK, and statistics in other western countries are comparable. Still, Moreno says Native Instruments was able to increase the female ratio from 17 per cent to 22 per cent in the past year. And “20 per cent of our leaders are female,” she says.

Increased diversity has real-world consequences on sexual harassment and discrimination, according to an article published by Pew Research Center, a non-partisan American fact-tank. Called Women in majority-male workplaces report higher rates of gender discrimination, the article detailed a 2017 study, which found that “women employed in majority- male workplaces are more likely to say their gender has made it harder for them to get ahead at work, they are less likely to say women are treated fairly in personnel matters, and they report experiencing gender discrimination at significantly higher rates”.

Data like that is hard to ignore, and raises important questions about the power of diversity policies on ending workplace harassment, to include adding diversity recruitment and retainment language to any potential industry-wide Code Of Conduct. Though Wheeler says it’s important to remember that while pushing for diversity is crucial, “tokenism is not integration”.

“Diversity is not just men and women,” she says. “If you’re going to talk about diversity, you have to talk intersectionality.”

Meg Wilhoite

Meg Wilhoite

Intersectionality generally considers diversity in broader terms than male and female, black and white. Class, race, sexual orientation, age, disability and gender all come into play, and are interwoven, and intersectionality is woven into the WHV Code Of Conduct. “Without intersectionality as a foundational principle, the Code would be a different document,” Fay Victor says. “Intersectionality informed the use of the term ‘safe(r)’ in the title of the Code, as an acknowledgement that feeling ‘safe’ is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. I consider it to be one of the greatest principles about the Code.

CEO of online music store Beatport, Robb McDaniels, says the company supports adopting a Code Of Conduct like the one written by We Have Voice across the industry, including additional diversity recruitment and retainment language. The company already follows Equal Employment Opportunity guidelines written by its parent company, LiveStyle, which outlines an intersectional policy regarding hiring. And McDaniels says: “We are in the process of modifying that to more directly reflect Beatport’s culture and history,” and that a written version is coming soon.

While female:pressure sees adopting an industry-wide Code Of Conduct as vital to addressing issues of sexual harassment and diversity, Wheeler and other members stress that any document is only the first step. “Okay, you signed on,” Wheeler says. “What are you doing about it? How do we set up an environment where it can actually change what’s happening? This is why it’s so important to look at how it’s implemented, because it’s great to get as many people on board as possible, but talk is talk, actions are what counts,” she says.

Ensuring victims have somewhere to turn outside of their company where problems can be reported anonymously, if so desired, is crucial to the success of any Code, the members of female:pressure say. “The fact that reporting is so public — this is why women don’t report,” Meg Wilhoite says. “They’re not believed or their concerns are not handled with enough care.” Because of this, reporting may feel like an impossible choice for victims. “Especially an intern/boss situation,” Wilhoite says. “That boss could make it impossible for that person to ever work in that industry again.”

Wilhoite suggests implementation of an Ombuds, an independent public advocacy system implemented in universities, governments and businesses around the world, with roots tracing back to China’s Qin Dynasty in 221 BC. Because an Ombuds operates independently and has no formal decision-making authority or disciplinary responsibilities, its main concern is fairness and conflict resolution. Ombuds offices are often trained to deal with harassment victims, offering counselling, education and training to help mitigate further issues. “They’re completely neutral and confidential — that really helped me,” says Wilhoite, who dealt with Ombuds during her PhD studies. “They were trained and had good suggestions. I think the industry needs to create an Ombuds.”

Similarly, the Association For Electronic Music (AFEM) and DJ Mag set up a hotline last year for people to report sexual harassment in the dance music industry. It’s operated by workplace health organisation Health Assured, and is staffed by trained experts who will listen to and support anyone who calls in. (The number to call is 0800 030 5182.)

“AFEM condemns harassment of every kind,” AFEM Regional Manager Tristan Hunt says. “Everyone has the right to feel safe and respected in their workplace or social environment, and we have committed to adopt and make available a Code Of Conduct for the electronic music industry that will clearly state the standards of behaviour expected from fans and professionals at every level in our scene.”

CRITIQUE

Not everyone likes the idea of an industry-wide Code Of Conduct. At IMS, Honey Dijon called the suggestion “disheartening”, and said it feels like implementing a “corporate structure”. This is something Carly Wilford and members of female:pressure acknowledge.

“You don’t want people feeling like they can’t live or can’t move or function,” Wheeler says. “If you wanna hook up, that’s awesome. But for somebody that does not want to be approached, there’s gotta be some clarity in terms of what’s okay. But it’s really not complicated to treat people with decency.”

“You don’t want to take the soul out of the industry,” Wilford says. “But at the same time, with so much money being made, that’s sometimes questionable anyway.” The electronic music industry had an estimated value of $7.3 billion USD in 2017, and that number is expected to grow. While money isn’t the sum total of everything important in electronic music, in some ways, it does point to the health of the scene — one that is diverse, inclusive, vibrant and global. And if that trend is to continue, changes may be necessary.

“There’s so much in our scene that’s incredible,” Wilford says. “But at the same time, if we want to ensure this has longevity, we need to step up and align ourselves with every other business to make sure we’re here for the long haul.”

Ultimately, Wilford sees adopting a Code Of Conduct as part of the wider discussion of mental health in electronic music. And for the sake of its future, she thinks the scene needs to take better care of its own. “Let’s put solutions in place to make sure we never have to have this conversation again,” she says. “What we have to remember is that we are paving the way for the next generation. Do we want our kids to grow up in the current scene that we’ve created?”

To learn more about Code of Conduct, keep up to date with female:pressure and We Have Voice Collective online