Solid Gold: How 'Music For The Jilted Generation' turned The Prodigy from rave outsiders to festival headliners

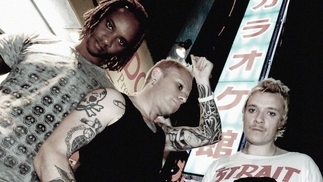

DJ Mag's new Solid Gold series revisits and examines the ongoing significance and influence of electronic albums throughout history. In our latest edition, DJ Mag regular Joe Roberts discusses how The Prodigy's second album, 'Music For The Jilted Generation', refined the Braintree trio as a voice of youth protest during a turbulent time in British history...

The rope bridge spans a wide ravine that fades into darkness as it drops. On one side, under skies choked by smoke being belched from distant factories, is an army of police. Pouring out of a riot van onto dry rocky land they're assembling behind a wall of shields, one officer waving his baton with violent intent. This menace is directed toward an idyllic scene that's separated only by the vast gulf between them. Here, sunlight fills the sky nurturing an expanse of green grass. In the distance, speaker stacks tower above a huge gathering of people. A lone figure stands in the foreground. At the beginning of the bridge is a long-haired raver wearing army boots, cut-off jeans and a black t-shirt. The middle finger of one hand is held up in defiance. His other holds a machete, moments away from severing the ropes that hold the only crossing in place.

At a time before digital downloads, when album artwork went further than simply a cover, this was the inlay that greeted those who bought The Prodigy's 'Music For The Jilted Generation'. Released in 1994, it was a year when huge protests had taken place against Section 63 of the Criminal Justice Act — a piece of legislation that gave police extra powers to break-up raves, and described the music played there with the famous phrase: “emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” One march ended with a giant free party in Trafalgar Square, the next violent clashes with the police around Hyde Park. Officials accused demonstrators of instigating the violence, but , one of the protestors' lone political defenders at the time, called police tactics "ill-conceived" after police charged at people who were attempting to leave, seriously injuring many including children. Against this tense political backdrop, the album's artwork was a bold statement — a literal fuck you to the forces of law and order who were happy to perpetrate criminality for their own ends.

This was a change of tone for a group whose first album, 1992's 'Experience', was built from soaring piano lines and the sampling of a cartoon cat. Opening with an eerie intro that featured the sound of a typewriter, the new script literally being written, a voice declared, “I've decided to take my work back underground, to stop it falling into the wrong hands.” First track 'Break & Enter' hammered home this point. A whirl of metallic breakbeats and smashing glass, social unrest was ingrained in the song's DNA, a repeating rave whoop now pained where once it had been ecstatic. Then came a vocal sampled from Baby D's piano classic 'Casanova', its refrain of “Bring you down to earth” signalling a flurry of dark beeps and synth lines that encapsulated both anger and grief, yet a determined sense to push forward regardless.

Speaking with Clash Magazine to mark the album's 20th anniversary, Liam Howlett, the master sampler and musician behind the music, stated that the now-famous picture was chosen before the Criminal Justice Bill was passed. Even if the album's mood wasn't intentionally reflective of the events surrounding the bill, the more personal reasons for The Prodigy's metamorphosis were still resonant.

"I remember standing on stage in Scotland, at a rave, and it just felt silly,” Howlett told Clash, adding that at one point the group had considered splitting up. “I was like: ‘What the fuck am I doing here? I’m not into this. It’s now so far from what it was.'” It's a sentiment that's many have echoed recently about the state of the current club scene.

The “Fuck them and their law” hook from 'Their Law', the album's second track, where Howlett defied expectation by teaming up with Brummie grebo rockers Pop Will Eat Itself, may have been as aimed at the conventions of the rave scene as it was the authorities shutting it down. Filled with grungy guitar lines and feedback, its acerbic, aggy energy coiled to less than 120bpm, it's about as far away from 'Experience' as it was possible to go. This uncoupling from the inanely happy sonics of hardcore they had begun with — keeping the breaks but adding a darker, gritter edge — also fuelled another iconic album track, 'Voodoo People'.

A reverence for live bands over the facelessness of techno helped steer The Prodigy to become festival headliners by the mid-'90s, including taking them to Glastonbury in 1994. It's a metamorphosis that happens before your eyes in the video to 'Poison', the album's last single. A slow acidic cut built around various funk breaks, a bare-chested Maxim Reality is recast as the group's lead singer with Liam playing drums, while Keith further develops the erratic dancing style that would eventually become his signature. Leeroy Thornhill, the band's long-limbed proto-shuffler who left in 2000, is already starting to look out of place in his baggy rave garb.

The album's first single 'One Love' was originally released as an anonymous white label called 'Earthbound 1' — a chance for the The Prodigy to test out that track's uplifting organ stabs and tribal chants without their name attached. Its success proved they could write an underground rave anthem if they wanted to. By the time of 'No Good (Start the Dance)', the album's top five hit, their need for underground approval was all but dead. Howlett's production genius beyond doubt, Kelly Charles' sampled lyrics, “You're no good for me, I don't need no body”, might as well have been written by him too, a producer shrugging off his past, a band pulling up the drawbridge and, for better or worse ('Baby's Got a Temper'), taking their own iconoclastic path. The video even features Howlett walking through an underground party, picking up a hammer in a back room to smash through a plaster wall. The barriers holding them back are a flimsy illusion — now they are free.

If there was a jilted generation in 1994, then there's another for whom this album still rings true today. Thanks to ever-tightening licensing laws and draconian legislation, councils are doing their best to shut down nightlife once again. The inevitable result is more free parties. After years of the corporatisation of clubbing, it's also finally getting its political bite back. Conversations about racism, sexism, homophobia and more have opened up not just political dialogue but also musical dialogue, with everything from EBM and industrial techno to jungle and gabber coming to the fore. For many, The Prodigy's marauding energy and no rules mindset were a gateway into this. With the world going to shit, it's time to restart the dance.