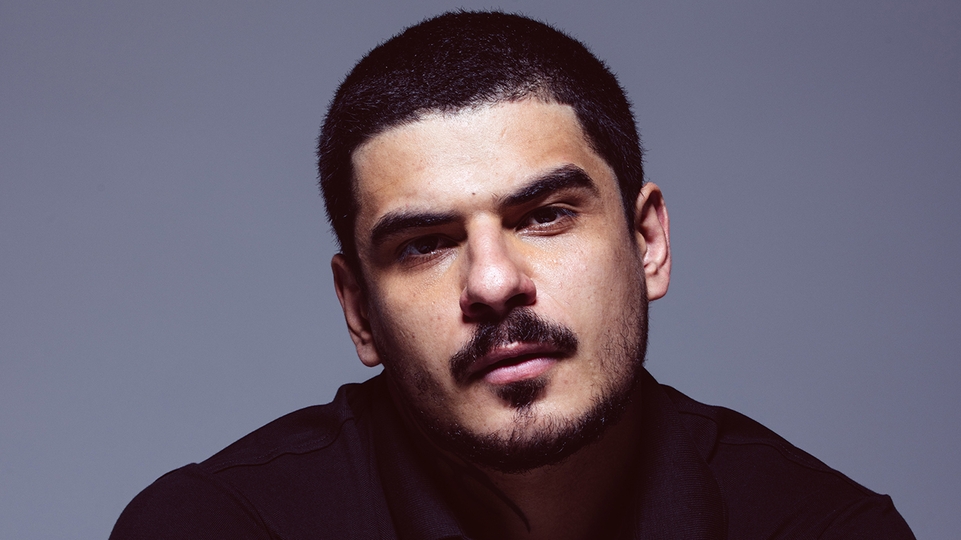

Vintage Culture: changing the game

Vintage Culture has come a long way from a small town in Brazil to playing stadiums, topping dance charts and partying with football royalty. After suffering near-burnout from constant touring, he’s recharged and full of vitality, with a deeper sound he loves with all his heart, hundreds of tunes ready to go, Ibiza and Las Vegas residencies scheduled, and a set lined up at DJ Mag's Miami Pool Party

Lukas Ruiz grew up in Mundo Novo, a tiny municipality with under 20,000 inhabitants, right on Brazil’s border with Paraguay. His mum had always told him it was a dangerous place. She very rarely let him out to play, too terrified he might get enlisted by local drug gangs or caught up in the gunfire of a cross-border deal gone wrong. He never saw any of the dangers himself. “It was always hidden from view,” he says, “but one day I lived it in my own skin. It was a game-changer.”

He was a young man at law school in Maringá, a big, shiny metropolis a few hours away. One weekend, he had returned home for a party at a friend’s house. “I was hanging out with a girl, just a friend,” he says swinging back on his office chair at home in Brazil, where he lives with his sister and mother. “This drug dealer thought I was trying to get with his chick. He might have been drunk, or high on drugs, I don’t know. But he got angry.” Lukas pauses and leans in close to the Zoom camera, cocks two fingers and points them between his teeth. “He put a gun in my mouth and said, ‘you’re gonna die’. That was quite an important episode in my life.”

It was a moment he will never forget, not just for the instant terror it brought, but also because it vindicated his mum’s “overprotectiveness” for all those years of his early childhood. “With the gun between my teeth, I thought, ‘OK, I’m doing law school, so one day I might have to protect a guy like this from going to jail. Well, I’m not doing it anymore.’” He told his mum he was quitting, and doing music full-time. By that point, he was already making beats. He had done since as far back as he could remember. “There was nothing else to do. My mum was super protective ’cause we lived in such a dangerous place.”

Mundo Novo is a town with just a couple of hotels, isolated in the middle of miles and miles of the farmland that Lukas’ late father worked on every day. Even searching today, Google results yield nothing but a couple of photos of a roundabout and two old news stories: one about a homeless man dubbed the ‘Canibal de Mundo Novo’ — you can do your own translation — and another about the shooting of a young man. “I wasn’t allowed out, and basically had to just stay in my room and find something to enjoy and pass the time,” remembers Lukas. “So I discovered music.”

It was his father’s collection that turned him on. “Older music, like sounds from the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s” and bands like Depeche Mode, New Order and Pink Floyd. “My dad loved Eurodance and rock ’n’ roll,” he says. “I was always super curious about how it was made, right from the start.”

There was no internet in Lukas’ house back then. “We weren’t, like, super, super poor,” he says, choosing his words carefully. His father worked as a farmer, and his mother had a small clothes shop. “But we were very... normal. No internet, no computers, no cell phones at all.”

One day, when he was around 12 years old, Lukas decided to head off to what he calls “a land house”: a bigger property owned by a higher income family. “I offered to work for them in exchange for access to the internet, some software and time to learn how to produce.”

Spotting his son’s interest, Lukas’ father brought him home a computer. “I loaded it up with software and for years I just did that to pass the time.” Eventually, it was time for college. Lukas agrees he “had a brain” and worked well at school, so was able to choose law. “To be honest, I was doing it for my father,” he says. “It was his dream that I became something like a lawyer, because if you talked about doing music at that time, my father, my family, they would never have gone for it, so I thought, ‘OK, you have to embrace your family’s advice,’ so I did it for them. But I was not in love with it at all.”

The course took him to the much more urban environment of Maringá, away from his parents, and free to do what he pleased. He was technically enrolled in the school for a year, but admits “I basically didn’t go to school”. Instead, he still spent all his hours making music.

“I was like, ‘what synths did The Pet Shop Boys use? What VST can be like that?’ The internet was my school.” By now, making music was by choice — he had caught the production bug and never wanted to stop. He got better and better, and one day uploaded his own rolling melodic house remix of Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick In The Wall’.

“I don’t really know why I chose that one to upload, because I did a lot of remixes of New Order, Men At Work, all the ’80s acts,” he says of the bootleg, which now has just shy of 20 million views on YouTube. “It was when SoundCloud was booming, and all the local DJs in Brazil were using it to find their music. Some of them played it, then some international people played it, and a few months later, people started trying to get me to play at their party.”

But that track was the only one Lukas was really happy with at the time. “I thought, ‘OK, I have to work on more until I have enough for a decent set’.” This was around 2014, and once he’d built up a modest catalogue, he started to play a few local parties once a month. He was still technically in school and was being supported financially by his mother. “I said to mum, ‘There’s no profession that I’ll get this kind of money’. It wasn’t much, but even a doctor didn’t get this kind of money in Brazil.” This, coupled with the gun incident at the party, is what led Lukas to do music full-time.

He began to play more and more, agencies came calling, and his profile grew in Brazil. “I did everything I could to deliver,” he says. “Me and my friends, we kind of created a movement in Brazil. Because at that time, 2013, 2014, it was the EDM boom, but people were starting to say they didn’t like it anymore. So we started playing slower sounds with a Brazilian signature they call Brazilian bass. I don’t like the name, but that’s what it was called, and it still is. It was a fusion of deep house and strong basslines.”

Around this time, the cost of the dollar against the Brazilian real soared. Superstars like Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike, David Guetta and Tiësto all hit the peak of their powers and started commanding higher and higher booking fees, which made them impossible to book in Latin America. “Brazil is totally different from the outside world,” Lukas reckons. “We have our own ecosystem and Brazilians were after another kind of music, so me, ALOK and Victor Ruiz, we were working on this different genre. People fell in love with it. It took over. Everyone started looking inside the country instead of outside, so we started to sell a lot of tickets to our events.”

But these spirited young entrepreneurs wanted more. They looked across the Atlantic at the success of much more established peers like Avicii and Hardwell. “We started to work as a company, we had our own video team, our own creatives. People didn’t do that here. We were the first. We also did merch, T-shirts and hats. We went on to play big festivals all over South America.”

Twenty-eighteen and 2019 proved to be Lukas’ biggest years to date. He made the cover of the Brazilian edition of Rolling Stone and was nominated as one of the most influential ‘30 under 30’ people in Forbes. He was in his stride, rolling out big tunes and playing even bigger sets. Then the pandemic hit.

“Because I was touring a lot, I actually thought, ‘thank God’,” he says, reliving the relief. “‘Now I have some time to stop and think.’ I had thoughts about life, about the sounds I was making and what I wanted to do, and I started to change the sort of music I was making.”

A period of “research” followed. “I always wanted to do something more progressive, more introspective. I love those sounds and I love tech-house. So I started to play longer sets, to work out what other music people liked, and what I loved.”

He knew it would be a hard sell. Brazilian crowds then were still very much tuned into “big drops” and, he adds, making a rattling sound with his mouth, “big percussion. So it was hard for them to understand a slower build-up, but they are getting there, and that is what I am trying to present now, this new version of me.”

One of the landmark moments in this stylistic shift came with his digital chart-topping remix of Maverick Sabre’s ‘Slow Down feat. Jorja Smith’. It has a fat, rolling bassline, but deeper drums, a tender and soulful vocal, and is smooth and seductive rather than energetic and explosive. “I started to get messages from producers I was a fan of, and I was like, ‘OK, this is it’.”

DJ Mag spoke to Lukas for the Top 100 poll last year, shortly after Brazilian football superstar Neymar had been encouraging his millions of fans to vote for Vintage Culture: “even though he doesn’t like electronic music so much, he was just out to support his fellow Brazilians”.

During the interview, Lukas said he had around 200 tracks ready to go. “Bro, I wasn’t lying,” he smiles. “The first year of lockdown, I released 24 tracks. I was producing all day, trying everything.” Before we speak, his European management team actually tells us they are trying hard to find ways to keep him out of the studio and to focus on the music he has already made.

One of his production sessions gave rise to ‘It Is What It Is’ featuring Elise LeGrow. It’s an immaculately produced vocal house tune perfect for deployment at big festivals in the sun. The stirring piano keys, slick bassline and effortless vocals all work perfectly. “I said to my friends, ‘This is a Defected song’.” He sent it off, but the label was not quite sold. “I sent it before I released the ‘Slow Down’ remix. When that came, Defected approached me again and said, ‘Let me hear that again’.”

They asked for a bunch of tweaks, which Lukas duly worked on. “They said to me, ‘You’ve only released with Spinnin Records, so give it some time.’ I did almost 100 different versions of ‘It Is What It Is’ until they loved it.”

As soon as Defected dropped the tune, it got worldwide radio and DJ support, and went high in the charts. Around the same time, his chunky remix of Louie Vega & The Martinez Brothers’ ‘Let It Go’ was released, and Vintage Culture had another hit. He had officially broken out of Brazil and was a name known around the world.

“I was doing stuff before that people were expecting from me,” he says now, looking back over this transitional period. “But I wasn’t really enjoying it. I wanted to change, but I didn’t want to be rude to my fans by switching from zero to 100 in a month. So I did it smoothly, and I am still doing it, and I am so happy about it.”

'I was doing stuff before that people were expecting from me, but I wasn’t really enjoying it. I wanted to change, but I didn’t want to be rude to my fans. So I did it smoothly, and I am still doing it, and I am so happy about it.'

He admits that his main aim is to create stuff that “I really love. I do this not to please anybody but myself. I want to put my soul into my music, which is what I was doing at first, but I had stopped doing it. Now, music is therapy. Even if I am making stuff not to play, just for fun, I love it. Like one day I was trying to do a track only with kicks, to make the kick a synth, to make the hi-hat the bassline. I don’t like to watch movies. I have never even been to the cinema. I don’t know how to drive. All of my life is around music.”

Lukas’ unhappiness at where he found himself, playing stuff he really didn’t want to play just to keep people happy, ran deep. Very deep, in fact. “When you get big, people put so much pressure on you,” he says quietly. “You have to deliver always, you have to be happy all the time. I like to play for a long time, but the people want more, and sometimes I don’t want to play more. So I was touring a lot, there were a lot of parties. I didn’t know about anxiety or depression. I was just not feeling anything at all. I didn’t want to play anymore. I just wanted to be alone in my studio or in my house producing or listening to music, but I knew that was not right.”

Fortunately, Lukas went to see a doctor and told him, “I am not loving what I used to love”. The doctor immediately recognised the classic signs of anxiety and the early signs of depression. “And we started treatment like three years ago, and now I feel better than I was in the beginning, because I know what I’m dealing with. I know my limits. It’s tricky, because it scares you, you know? To say I was not enjoying doing what I love was crazy. I was getting good money, I had a perfect life, why was I not happy? But now I know this is so normal for DJs. And I think we should talk more about it, because we can support each other.”

He says he often gets messages from fans who tell him “I was in a dark place but your music has saved me”. For that reason, Lukas says it’s important to fans as well as other DJs to talk about mental health. “We are all human. Fans think you are a perfect person because you’re in a different position to them, you have no problems, your life is great, so you have to smile and be happy all the time, but it isn’t like that. It’s not like the problems don’t exist because you have money or are famous, even if you are the king.” He plans to address this with, of course, a new song he is working on. “I wrote lyrics like ‘I’m not a hero’ as a message from me that we are all equals.”

Despite what he says, Lukas is very much a hero for a generation of young Brazilians. For him, that role was taken by genius Formula 1 driver Ayrton Senna. He died in a tragic crash in 1994, a year after Lukas was born, but remains a towering national icon in Brazil. When we speak, Lukas is wearing the great driver’s trademark blue cap, with his signature on one side and the Nacional sponsor on the front, while his laptop is adorned with a sticker of Senna’s famous yellow helmet.

“He died before I can remember, but later I discovered all about his past and what he did for the people. And that’s why I became a fan. Actually, as soon as I started to wear this hat, I became famous!” laughs Lukas. “His strength to chase against the odds, to never give up and always give his best, that inspired me so much. He was so focused on his goal and on winning. I am super focused too — 24 hours a day, my life is music.”

Senna’s legacy lives on through his foundation, which raises millions of dollars to provide schooling, among other things, to the millions of underprivileged kids in Brazil. And Lukas, too, has form in that regard, having raised $100,000 for his own COVID-19 relief fund in Brazil via his Só Track Boa brand. Its name is a slang term he used to use with his friends, which translates loosely as ‘good tracks only’, and is now a well-established party and record and fashion label.

“We started doing podcasts, then we started the label because that’s what we saw lots of DJs doing. Then one day, we asked my agency if we could have three or four of the DJs together for one party. That was for the first festival in 2016, and it was a huge success.”

Só Track Boa festival is now one of the biggest in Brazil. The most recent event, just before the pandemic, was in a stadium filled with 30,000 people, which is a crowd that even the most celebrated DJs in the world struggle to pull in Brazil.

What stands it apart is the production. His European management team tells me Lukas often spends a huge amount of his earnings on out-of-this-world pyrotechnic displays for his shows. He has also been known to have teams of up to 30 people at the shows, filming them all and making content for social media. “I think ALOK was the first to give that importance to the production,” he says, “but I do it because I want to give the fans the best time of their life. So it’s a mix between music connections, friendship and a new experience. I want people to know that when they come to see me, they get something different. I see that as an investment into the people to keep them coming back, you know?”

Lukas is keen to remember “his people” as well as his fans. He likes to grow alongside the team that has been there since day one. For example, just before Christmas, he played two eight-hour sets, one on 23rd December, and one on the 24th. The first was for a promoter he has been with since day one. Back then, around 10 years ago, only 200 people would come. For this one, there was a crowd of 10,000. “My team has basically been the same since the beginning,” he says, proudly. “I have had proposals from everyone, all over the world, but I like to maintain my roots, to stay with people that trust me, to have this empathy from the people who were there at the start.”

Unlike many DJs from older generations, Lukas happily embraces all aspects of his career. “The music is the most important thing, of course, but I love the business side too. I do work a lot on that,” he says, before going on to talk about monitoring the metrics of his releases, “total streams, chart positions, playlist reach, the number of playlists supporting Vintage Culture tracks.” For those interested, he has over 1.5 billion global streams to date, more than eight million followers on social media, has topped the Billboard Hot Dance and Spotify Dance Charts, and had three songs simultaneously in the Top 10 on Beatport, including the No.1 Main Chart Overall with that debut Defected Records single, ‘It Is What It Is’.

Despite all those measurements, he maintains there is still one standout way to measure success. “Playing an unreleased song to a crowd is the best. Real people, real feedback. If it doesn’t work, you’ll know immediately. Goosebumps never lie.”

Now back on a better path with his mental health, Lukas is loving life. Like, really loving life. Though he is friendly and engaged at the start of our interview, he begins to shuffle and shift about in his seat more and more over the course of 90 minutes. He looks tired, maybe from a late-night party, maybe from a late-night studio session. “I love to party,” he says, and his reputation backs that up. His manager says he is “the biggest rock star DJ I know”. Tiësto calls him “the man who never sleeps”, while Chris Lake was more direct on one of his recent Instagram posts: “You’re a madman!”

“I love after-parties,” Lukas explains. “I just love to play, so that’s the main thing. Like, in January, I did a 24-hour set. It was amazing. In all my sets, I don’t like to play for less than three hours. For me, there’s no point to playing less than that.”

Lukas reckons his love of playing long goes back to his childhood and the fact his mum never let him out. “One time, I snuck out to a rave and my mother turned up — she was beating me in front of my friends! So I never got influenced by any DJs. I didn’t become a DJ because I saw them playing. The fact I am like I am today, partying so much, I think I owe that to my mum.”

It’s even crazier to think what has happened given that when Lukas took his first booking, he had never even DJed. “I was like, ‘OK, I have this gig and I don’t know how to play’. So I had my laptop and was looking at these psy-trance guys from Israel. They were playing Ableton Live so I went on the internet, got a copy, and learned how to do it on that.” For five years, he used that setup.

“I had very raw skills. The crowd really didn’t care what I played with,” he says. “They are just there to have fun. But I was feeling people looking at me funny when I started touring and was still on my laptop. And also I was feeling that I wanted to achieve something more. I wanted to get away from my comfort zone and start to play with CDJs, so when the pandemic hit was the perfect time."

Whatever he is doing, it’s worked. This summer, Lukas will curate 16 of his own dates at Hï Ibiza, as well as hold down his first-ever residency in Las Vegas. On the White Isle, he promises to mix up plenty of his DJ friends from Brazil with the sort of DJs who inspire him today. “We will mix it up between house and progressive, and of course, there will be huge production!”

When we ask what it’s like for a boy from a small, dusty town in Brazil to be headlining in Las Vegas for high-end clientele, Lukas swings back in his chair once more. “This is so crazy — 10 years ago if you said that, I would not believe you. My main dream was an Ibiza residency, but I thought it would be many years away.” He catches himself, before continuing. “But bro, it’s important to remember where you came from, so I have a friend who I grew up with who comes to work with me. I need his energy. He is a DJ now, called Mecca, and doing so well. He will play with me at Hï Ibiza and he gives me that balance on tour. The energy on the road is crazy. You can get fucked up, so it’s important to my health to have people that know me as Lukas, not just Vintage Culture.”

Although his earnings as Vintage Culture show in some ways — he wears high-end designer clothes like Moncler, Amiri and Palm Angels — in other ways, Lukas very much keeps it real. For instance, he still uses the same VSTs and music-making setup that he did when he first started, rather than fetishising the expensive hardware many producers turn to. “I like studios, but I feel more comfortable doing music on the sofa or wherever the inspiration comes. All you really need are your ears and a decent laptop.”

To keep up with his often relentless schedule, Lukas these days thinks of himself as an athlete, as someone who needs to take care of himself. He goes for a run or does some sort of workout every day, and every week he goes to the doctor. “He does all sorts of checks on me, sports medicine stuff, and gives me the vitamins my body is missing.”

What he mostly craves, though, are those long DJ sets, those connections with people that he says “gives me life”. Just before we speak, he has been to a friend’s wedding, and yes, of course, he DJed: “for eight hours!”

He will soon head to Miami to play the DJ Mag Pool Party, and it will be something of a homecoming gig after he spent a few months living there during the pandemic. In the meantime, he has another wedding, this time one he will attend in a professional rather than personal capacity at the request of someone from Brazil’s high society. Incidentally, it won’t be his first time mixing with Brazilian celebrities because, in the past, he has danced in Ibiza with legendary retired striker turned notorious party animal, Ronaldo.

“I asked them, do you want a ‘Vintage Culture experience’ or do you want to hear the music I really love?” he says. “They said I can play what I want, which is just how I like it.”