Carl Cox is still searching for his perfect techno sound

After more than three decades of DJing all over the world, Carl Cox remains one of dance music’s most beloved figures. With a new album on the way, and a fresh emphasis on live performance, Bruce Tantum speaks with the king about his incredible journey so far, and his determination to keep challenging himself

When his bespectacled face pops up in a Zoom call, Carl Cox is sitting within a well-appointed studio space, in front of all manner of modular synths and effects gizmos, in-wall monitors and a slightly humongous computer screen. At least, it appears as though that’s where he’s sitting. It turns out that he’s actually at his home in Hove, on the south coast of England, just west of Brighton; the studio we see is actually a short drive from his other home in Melbourne, Australia.

“It looks pretty good, right?” he asks, his boisterous laugh coming early and often over the course of a long conversation. “But yeah, this is superimposed.” He bobs his head around to prove the point, pixels dancing around his shaved head. It turns out the studio is situated on a farm that once grew apples for cider, and is set up in what used to be the cidery’s cool room, where the finished product would be stored to prevent spoilage. “I really wanted something that was cool and inviting, with good sound,” he says. “And the sound is incredible. I love it — I’ll get my hands on things, straight away, and just do something.”

“Just do something” could be Carl Cox’s motto. He’s been doing lots of something, actually, ever since he was a kid in the ’70s and a budding young DJ on the rise in the ’80s. Decades later, he hasn’t slowed down an iota, it seems. He’s just returned to his Hove abode from a busy period of travel and touring a few days ago — but he’s not home to rest, exactly. “When I landed, I did a show for my record label, Awesome Soundwave [aka ASW], and then there was a Carl Cox Invites event in Madrid at a club called Fabrik, which was crazy,” he says. “And then I’m back to my house for one day, then we’re gonna jump back on the plane again over to the French Riviera to Cannes, for an event for Prada.”

Does this man, the one who’s referred to by some as the King of Techno and by others as the Three-Deck Wizard, ever stop? To hear the veteran DJ, producer, and industry insider tell it, the answer is and always has been an emphatic “no”. Almost to prove the point, at 59 years old, he’s got a new album, ‘Electronic Generations,’ coming out in September, along with a new emphasis on live performance, a new summer residency in Ibiza, a label to run and, it seems, about a dozen other things. And somehow, on top of all that, he found time to pen an autobiography, Oh Yes, Oh Yes!, published late last summer. But for Cox, it has ever been thus.

Growing up in South London, Cox had a relatively normal childhood — riding bikes, kicking a football around, dropping a fishing line into whatever bodies of water Sutton had to offer, school discos. But there was, perhaps, a bit more music than in most happy childhoods. His father was a consummate host, he says, “always playing music for his friends, who’d come around and listen to the records he really enjoyed. My mom was always supporting my dad, based on the parties we had at home. It was always a happy home, with the music as a backdrop to our life.” When his father wasn’t hosting a listening session, Cox would take matters into his own hands, putting on headphones and scanning the radio airwaves for the funk and soul he was falling in love with.

“I’d find something like the O’Jays’ ‘I Love Music,’” he says, “and be like, ‘right, yeah, there we go.’ Or ‘Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone’ by the Temptations — wow, what a record. And I’d go find those records. Anything that came out of Tamla or Motown Records, I followed it. Anything that came out on Stax Records, followed that. Atlantic, followed it — the list goes on. I wasn’t collecting baseball cards — I was collecting records.”

Cox had already been experimenting with mixing tunes, recording off the radio onto a cheap reel-to-reel recorder, using a Realistic mixer to try to segue the songs to get a continuous-play mix. But eventually, he convinced his mother to help him upgrade his gear. “My mum used to get mail-order catalogs from Freeman’s,” he recalls, “where you could browse underpants or kitchen utensils or suit jackets. You could even get yourself some chandeliers — or a disco unit. Wow, a disco unit! It was an all-in-one unit: amplifier, mixing console, and two very cheap turntables, belt-driven. It was like £572, which was a lot of money at that particular time. But my mum said, ‘I'll get it for you. And it’ll be two pounds, 75 pence a week, for about a million years, to pay for it.’ Which I thought was a great deal! So she ordered it, and it turned up: two big speakers, got the console, everything. And that was the beginning of my career right there.”

The unit itself was no great shakes — they were belt-driven turntables, for instance, and the belts would constantly pop off of the platters. But it was good enough for Cox to begin to master the mechanics of beatmatching, even though the decks had no pitch control. “I would have two copies of the same record, like this record called ‘Inherit The Wind’ by Wilton Felder — his saxophone on that record is so beautiful,” he says. “I thought, ‘right, let me put two of that same record on at exactly the same time. Which one is going to end first?’”

Sure enough, one turntable was ever-so-slightly faster than the other, and one of the copies ended before the other. “So if a record was, say, 121bpm — I would do a count on my watch to get the bpm — I would put that record on the slower deck, and a 120bpm one on the faster deck. Therefore, in some sort of genius way, I figured that they could then stay the same tempo. I learned a lot like that in my bedroom, for at least five years — literally just learning, understanding, practicing, mixing music before I even went out to do it.”

"There were other DJs that learned three-turntable mixing, but I was the only one who did it all of the time. People booked me because they wanted to see what it was all about"

Cox began taking on mobile gigs; in the 1980s, he graduated to club DJing. “A club called Xenon’s, another called Aladdin’s, a place called Scamps, some others — none of them are there anymore,” he recalls. He’d open for DJs like London clubbing pioneer Trevor Fung. (“I remember doing an interview once, a long time ago,” Fung once noted on the DJ History website, “and they said, ‘Who do you think is your up-and-coming DJ?’ and I always said, ‘Carl Cox.’”)

At first, Cox was selecting largely from his funk and soul collection, with hip-hop added to the mix as the decade progressed. But soon, a new sound began to emerge. “When electronic music started to be made in America — the music coming out of Chicago, Detroit, and New York City, a lot of stuff like early Trax Records — I was like, ‘electronic music, here we are,’” Cox says. “But I used to clear dancefloors, playing that music. I’d put on ‘Time To Jack’ by Chip E., and it would be like, whoosh!"

But by the time of the UK’s ecstasy-fueled Second Summer Of Love in 1988, those dancefloors had caught on — and then some. "They wanted more and more and more, and I wanted more and more and more," he adds

By that time, there were dozens, probably hundreds, of DJs spinning the new sound of house in the UK. Thanks to his years of beatmatching practice, Cox had a head start on many of them — but just like the dancers, the DJs soon caught on. He needed something that could make him stand out. “I felt that I needed to have something which people could only wonder about,” he says. “I felt that if I could pull off DJing with an extra turntable, it’d be awesome.”

Easier said than done, though — first up, he didn’t yet have the money to buy a third Technics 1200. He finally was able to borrow one, but there was another roadblock: Other than in the highest-end clubs, most mixers at the time had only two phono channels, plus an auxiliary channel and a tape channel.

“Eventually I figured out that I could take a smaller mixer and use that to create an input loud enough for the auxiliary to be used as a third channel. So even that was a bit of a process.” There were other practical matters to figure out as well. “Like, where do you even put a third turntable?” he asks, laughing. “Most places had barely enough room for the mixer and two turntables. It would end up that one would be at the front, or one would be over at the side.” But the payoff was immense.

“Once I worked out what I was doing, it was like remixing other people’s music, live,” he says, still seemingly surprised at the discovery. “That gave me a completely different energy than any other DJs at the time. There were other DJs that learned three-turntable mixing, but I was the only one who did it all of the time. People booked me because they wanted to see what it was all about. Like, is he a one-trick pony? Was this just a lucky break? No. I was using all three turntables, just going for it — and I was very comfortable when I started to be called the Three-Deck Wizard. That is the very thing that catapulted me into becoming the main slot DJ.”

By the early ’90s, Cox was playing raves, some of them massive, around the UK — but even then, and even with his three-deck technique, Cox felt as though he needed something that would let him stand out from the pack. His solution: Mix the breaks-heavy sound of UK rave music of the time with the straight-up wallop of techno. “Rave music would be the breakbeat, techno would be the 4/4 stomp, and I’d go in between those elements of rave and techno music, which nobody was really doing at the time,” he explains. “Like, if Jeff Mills was playing a set, it’d be techno. If DJ Seduction was playing a set, it’d be breakbeat. You wouldn’t get anyone playing both, but that’s what I did, and it helped me to stand out from everyone else. You’d be dancing away to the Prodigy, and then on the other side of that, it would be Caspar Pound or somebody, smashing the kick drum on the 4/4. And the only way you could do that, and really do it well, was by three-turntable mixing.”

Just as with DJing, Cox had been working on honing his production skills long before he’d actually released anything. He started out by laying down tracks on a cheap Tascam multitrack recorder, bouncing the tracks around and coming up with ideas. “But it was quite loose — I’d be counting ‘one, two, three, four’, trying to keep everything in time as I’m recording,” he recalls. “It was really good learning for me, and I wanted to learn more, but going into a recording studio was really expensive. So I used to sit in on sessions with friends of mine who were engineers working on certain tracks for people.”

The first official record credited to Cox was 1991’s ‘I Want You (Forever)’, released on Paul Oakenfold’s Perfecto label — but before that, he’d flexed his fledgling production muscles with a breakbeat track called ‘Let’s Do It’, originally released as an uncredited white label in 1989. “There was a record by Landlord [aka Canadian producer Nick Fiorucci] called ‘I Like It’,” he says, “and another record by another unit called Success-n-Effect, and I manipulated the beats through a Numark mixer which had a four-second sampler on it. I laid it down into my Tascam and recorded it. And it was a massive hit!”

But it was ‘I Want You (Forever)’, a near-perfect rave-meets-pop number, along with its early-’90s-time-capsule video, that turned Carl into a star, one that beamed far beyond the raves. “To be honest, it put me in a different category of who I am as an artist and a DJ, even though I’d never really pursued that.” At the time, though, he was somewhat indifferent to his newfound success. “I just kind of went, ‘Okay.’ I didn’t go out and do live PAs; I just went back to the DJing again.”

Eventually, though, he did perform live, at least for a time, under the Carl Cox Concept moniker. “But the setup of a live set, the cost of the extra people you’d need and everything, was too much for a lot of promoters,” he says. “And for me, it was double the amount of work for the same amount of money. Also, playing live was always like flying by the seat of your pants. You know, we were using floppy disks at the time, and the machines didn’t have much memory. Things would crash — like, if I plug one more thing in, will everything fall over? So after about six or eight months of playing live, I’m like, ‘Right, I’m not doing that anymore!’ And when I got back to DJing, my popularity went from here to there,” he adds, raising his right hand from shoulder height to as high as he can possibly reach.

One measure of his success was by record sales. “When I put out my compilation album with React Records in the UK [‘Carl Cox – F.A.C.T.’, released in 1995], we were only expecting to sell 12,000 to 15,000 units total,” he says, “but in its first week of release, we sold 25,000 units.”

That first F.A.C.T. compilation — the acronym stands for ‘Future Alliance of Communication and Tecknology’, by the way — went on to sell over 500,000 units, a near impossible number for a DJ comp even in those peak-CD-sales days. “It’s the biggest compilation album of dance music that I’ve ever sold,” he says. “And it wasn’t commercial. What it was, was everything to do with my experience of who I was as a DJ.”

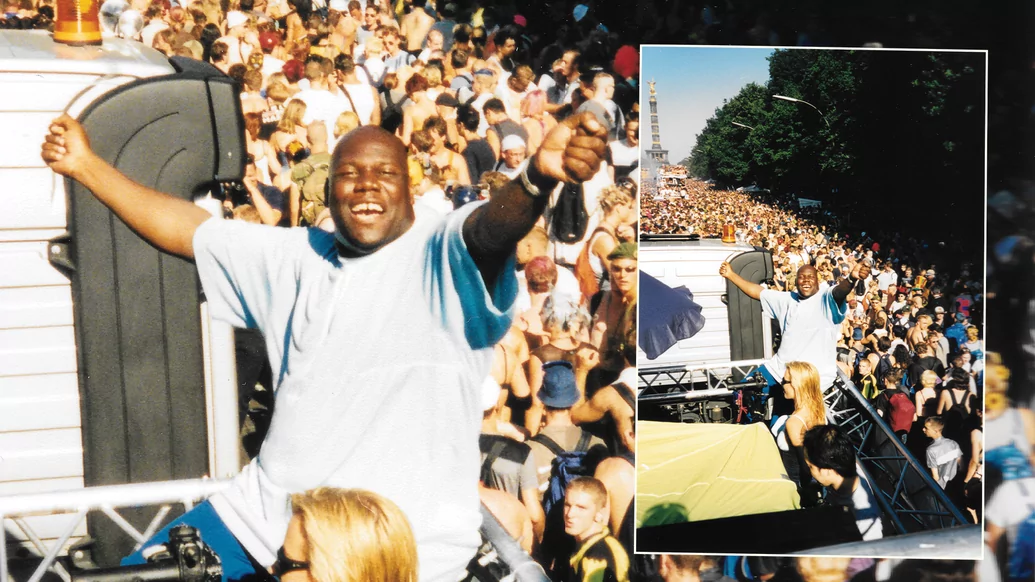

The gigs were getting bigger, too. In 1997, for instance, Cox made his debut at Berlin’s Love Parade in front of 1.5 million people. “France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and the rest of the world were calling, and the demand for me was definitely nonstop,” he says. By the time 1997’s ‘F.A.C.T. 2’ came out in the US via the Moonshine label, followed by the debut Moonshine Over America bus tour — that year’s lineup also featured Tall Paul, Keoki, Cirrus, John Kelly, and Omar Santana — the United States was his as well.

In the decades since, his career has seemingly been on cruise control: Club dates, releases, festivals, compilations, more gigs, repeat. It would be enough to wear a mere mortal down. It’s quite possible that Cox suffers the drudgery, the angst, or the occasional bout of existential dread that the rest of us are prone to suffer, yet over two hours of conversation, he shows little sign of such burdens — the closest he gets is when the subject of the pandemic and subsequent forced hiatus from that constant gigging comes up.

"For 30 years, I had not stopped at all. It took a pandemic to stop me. I sat there and took a breath and took stock of what’s going on around us. But you know, the pandemic really shook up the industry, because it is all getting way too easy and blasé. People were like, ‘Yeah, I’m a DJ, give me millions’"

The final party that Cox played before lockdown was at Houston’s Stereo Live. “That particular night,” he recalls, “I turned the TV on, and Trump was saying ‘Right, we’re closing our borders. If you’re gonna leave, leave now.’ But I played that one last night. I was only supposed to play for three hours, but it ended up being seven. Nobody wanted to leave the club. Tequila, champagne, like it was going to be the last party on earth.” The next day, he returned to Australia, where he figured there would be a few weeks of laying low before he could get back at it.

“And then it’s like, oh, two more weeks,” he says. “And then, two more. Oh, okay. It wasn’t long after that, that I realized, well, we’re not going anywhere. For 30 years, I had not stopped at all. It took a pandemic to stop me. I sat there and took a breath and took stock of what’s going on around us. But you know, the pandemic really shook up the industry, because it is all getting way too easy and blasé. People were like, ‘Yeah, I’m a DJ, give me millions.’

“But I do care about the scene and care about the music, and that’s the reason why I started Cabin Fever,” he continues, referring to the live-streaming show he revved up soon after lockdown. “I wanted to basically give people the history of who I am. I didn't need to do a show to further my career, or to remain relevant. I think people know who I am. But in the meantime, for 52 weeks, this very studio you see behind me was turned into a live-streaming studio.”

There was a bonus: After years of playing digitally, it gave Cox the excuse to get the turntables out again and to reconnect with his love of vinyl. “There were records I’d completely forgotten about, but I was experiencing how they sounded when I first got them — like, wow, what a tune!”

Lockdown also afforded Cox some time to relax. He puttered around his garden and his kitchen; a video of him baking banana bread went viral. When the subject of that video comes up, he lets loose with yet another of his hearty guffaws. “The thing I know about banana bread,” he says, “is that having one piece of banana bread is alright. But having a loaf of banana bread isn’t alright at all! When I went and made that video, what was really good about it was that it got people to see me not as a robot DJ, but someone that actually does live at home. It had nothing to do with music, but the beautiful thing about that was it gave people another way to connect with me.”

“I will continue to DJ sometimes. But what pushes me further, far more than anything else right at the moment, is going live. I’m not here to prove myself in any way, shape, or form. I think I’ve done that many times. But this is the future for me”

It also gave him more time to indulge his other passion: motorsports. It’s a subject that seems to get him as excited as music does. And it’s not just talk — he claims to own “over 25 supercars and classic cars” and 65 motorbikes. “I have a Ferrari Roma,” he says, reeling off a few of his faves. “I have another McLaren 570S Spyder, which is just a beautiful car. I also have a Honda NSX. It was very cheap in the realm of supercars. Looks good, is good, going to be a future classic. I love my Porsches, so I have a Porsche 911 GT3 RS, a white one from 2016. I have a 2010 Porsche 911 Sport, very limited edition. I have a 1983 Porsche Carrera. You can imagine how old-school that one is! It actually feels like a Beetle, but it’s got beautiful lines. In my American muscle cars, I have a Pontiac GTO, 1965. There’s a 1968 Dodge Charger, which is very Dukes Of Hazzard. I have a Mustang Fastback from 1965, a black one, and I’ve got a GT350 Shelby Mustang.”

He goes on to mention yet more Mustangs, and a 1964 Corvette Stingray (“It’s very fast and a little scary”), a Plymouth Road Runner, and a seemingly endless list of others, extolling the virtues of each one. That’s followed by a recitation of the race teams his organisation, Carl Cox Motorsports, has worked with, as well as the awesome speed of his very own drag car (“At the top end, it really looks like a bullet being shot out of a gun”). Clearly, the power of motor vehicles gives him as much pleasure as the power of music.

Even with his hefty discography, even with a new album on the way, Cox is first and foremost, in the minds of many, a DJ. There’s obviously good reason for that — he’s one of the best at what he does, after all — but over the years, rumours of his imminent retirement from the DJing arts have occasionally surfaced. Some of that scuttlebutt arose when Space Ibiza shut down, and he lost the longtime White Isle residency he had there; it came again during lockdown. Most recently, the rumours began to swirl again a few months ago when he unveiled what he’s calling his Hybrid Live set at this past March’s Ultra Music Festival, where he’s long hosted his own stage (first dubbed Carl Cox & Friends, and more lately Resistance).

The ‘hybrid’ of the name is a bit misleading — his Ultra set seemed to be almost entirely live, with various modular synths, a Roland TB-3 (based, of course, on the classic 303), a Roland TR-8S (“sounds a bit like a 909”), and more, all running through Ableton Push.

“It all keeps me really busy! But it’s given me a whole new feeling of energy,” Cox explains. “And DJing has gotten far too easy. You’ve a sync button, you’ve got a thing on there that can put it into key, and you can blend it beautifully, and it works. It’s art. But it can become a bit linear. I still want to bring my own funk and sexiness to techno music, and I want to be the one to create it, rather than just rely on a record that I’m playing. With Hybrid Live, I’m making music that we have no clue ahead of time of what it’s going to be. It’s happening in front of you as an experience. You walk away from it and go, ‘Wow, what was that?’ I don’t know what it is myself, but when it comes together, I’m excited again.

“To go back to DJing,” he asks, “is that taking a step backwards for me? Yes, I will continue to DJ sometimes. But what pushes me further, far more than anything else right at the moment, is going live. I’m not here to prove myself in any way, shape, or form. I think I’ve done that many times. But this is the future for me.”

A big part of that future, at least for the short term, involves the imminent release of a new Carl Cox LP — ‘Electronic Generations’ marks his fifth album of original work overall, and the first since 2011’s ‘All Roads Lead To The Dancefloor.’ “The tracks on the album, I didn’t make them for any specific purpose, and that attitude has become my power,” he says of the album’s creation. “For this album, I just got on the machines and absolutely hammered them. It’s kind of like going back to where rave was to begin with. It was this powerful thing which you felt and which you somehow understood — and this album is all about that pure, raw, unadulterated power.”

Leading up to the release of ‘Electronic Generations,’ a series of remixes will first be hitting the digital shelves — the first two, Norman Cook’s reimagined version of ‘Speed Trials On Acid’ and Nicole Moudaber’s propulsive take on ‘How It Makes You Feel,’ are already available. And for those with a yen for travel, he’ll be unveiling the album’s cuts via a live showcase at London’s Wembley Arena on September 17th.

There’s still a label to run, of course. Awesome Soundwaves, which Cox heads up with partner Christopher Coe, is another facet of Cox’s love of live electronic music. “I wanted a label which had nothing to do with DJ culture,” he says, putting the emphasis on “nothing”. “I won’t sign anything by you unless you can go out and perform it live. I’ve had enough of people ghost producing, or just making music in the studio. No — stand by your music! Start from the beginning, Go out and perform live music, create your fan base. We need to see the next Prodigy; we need to see the next Orbital; we need to see the next Underworld. I mean, there are enough DJs in the world now — but there are all these artists in their bedrooms, making music that’s mind-blowing, but they don’t know how to get booked. I can’t have that.”

And then there’s a new residency in Ibiza at DC10, which will feature sets — some DJ'd, others live — from a lineup that boasts Laurent Garnier, John Digweed, KiNK, Surgeon, and Victor Calderone, among a slew of other heavy hitters.

It’s going to be a busy summer — and, very likely, busy fall, winter, and spring as well. Cox is now well into his fourth decade of this schedule, and it must wear on him at times. Does he think he can keep it going for yet another decade? “I really don’t know,” he admits. “But if I look after myself — eating well, sleeping well, enjoying the moment — why not?

“I think I’m always gonna have my techno head on. Still making music, still trying to find that perfect sound, trying to find that ‘I Want You (Forever)’ moment. It could come tomorrow, or it could come later. Who knows? I don’t. But I’m certainly going to keep trying.”