Congo Natty: junglistic soldier

On his upcoming 25-track opus ‘Ancestorz’ — which he describes as his life's work — long-serving jungle soldier Congo Natty unites many voices from across the diaspora, joining dots through the history of Black music and celebrating the new jungle generation. In a series of in-depth interviews for DJ Mag, he talks to Dave Jenkins about love, revolution, unity, and reclaiming his place in the history books

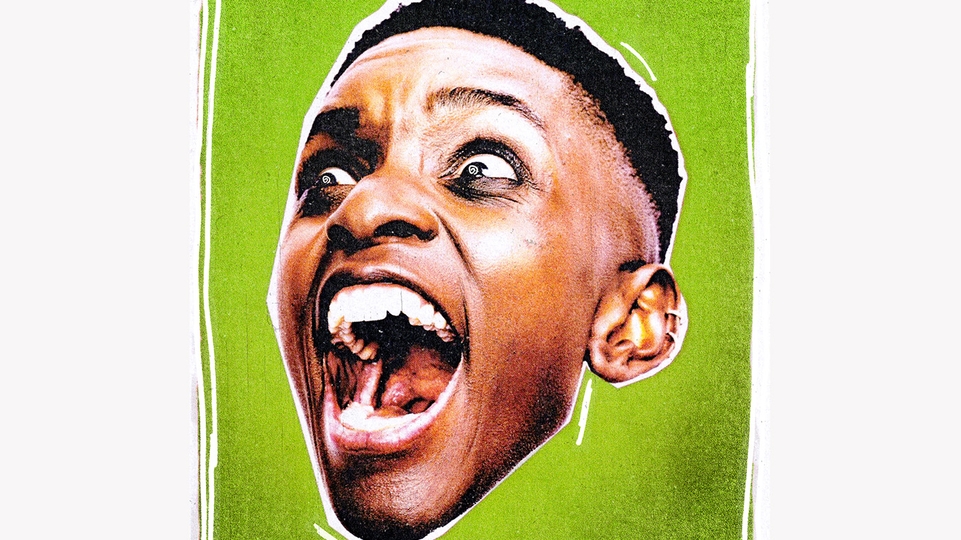

“This isn’t an interview, brother, this is an outerview!” Congo Natty declares. He draws on his spliff, holding DJ Mag’s gaze with intensity. Even through the filter of a video screen and a cloud of smoke, there’s a sense he’s looking directly into your soul. He speaks with equal levels of earnestness, humour and fierce passion and never seems in a hurry. A pioneer and originator, he’s been in the trenches far too long to rush to do anything insincere.

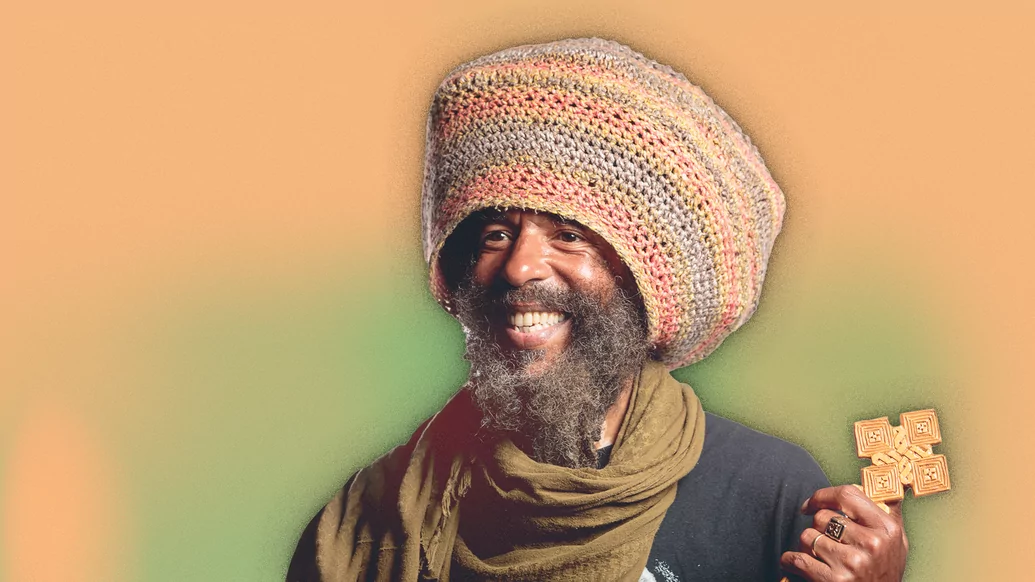

We speak on a number of occasions. Each interchange is several hours deep as we discuss everything from his Rastafarian faith to the many locations that are dear to his heart: his Tottenham upbringing, his time living in Haile Selassie’s promised land of Shashamene, Ethiopia, his time recording in Japan, Jamaica and Zanzibar, his Welsh maternal roots in Llandrindod Wells and his family home in Ramsgate. At points he’s animated, at others he’s stoic. At all times he’s fully engaged.

“All these years jungle has been the tortoise,” he considers. “We’ve held our position while others have been the hare, rushing around from here to there. This story could have been told 30 years ago, but no one wanted to print it...”

There are lots of stories to be told. The overview of this outerview, and the main story relevant to Congo right now in 2022, is that he’s about to drop his most ambitious and accomplished album to date. ‘Ancestorz’ is a body of work that includes many voices, tales and talents from across myriad generations, continents and disciplines. A jungle journey for the ages featuring collaborations with artists ranging from new-gen jungle sensation Nia Archives to jazz sax maverick Shabaka Hutchings, UK hip-hop premiership Klashnekoff to dancehall royalty Courtney Melody, via his own daughters Kaya Fyah and Princess Lydia; no other album in this artform has ever attempted to dig as deep or travel as far to unite the diaspora, join detailed dots through the history of Black music and celebrate and authenticate the new jungle generation. Without hyperbole, ‘Ancestorz’ is his life’s work. “This began when I was in my Welsh mum’s belly!” he smiles, before explaining how he’s never likely to make another album again.

“Only when my children have had the opportunity to do the same,” he considers. “Now is the time for the new generation and we cannot make the same mistakes again! You can try and stop Congo but you can’t stop our children...”

This is the underview of the outerview: For Congo, if the story of ‘Ancestorz’ is to be told correctly, it must also include stories of suffrage and unpaid dues. “Jungle has not been treated fairly at all!” he exclaims. “We’ve been underrated all this time. We have a community that is rife in depression, anxiety, loneliness and addiction. We have veterans and pioneers out there, man who carved this music into what it is with their bare hands, working to pay bills and break even when they’re in poor health and should be healing and celebrated. Working themselves into early graves. It’s a travesty!”

Inter, outer, over, under; fundamentally this is a story of consciousness, how music in the 20th century had incredible moments of unifying energy and how jungle is part of that lineage, but has never been celebrated in the same way as other cultural movements. “We need to pay attention to the timeline,” he says on more than one occasion. “John Coltrane changed the world in one LP. He took jazz up there with a higher consciousness so the youngers could come up there to. Reggae has a timeline. Hip-hop has a timeline. Jungle has earned its place to be investigated, and in the same way too.”

Investigations are happening as you read these words; more documentaries are being made and more books are being written about the unique UK movement than ever before, and the current appreciation of jungle, its roots, its new generation and its renaissance hasn’t been this strong since the early ‘90s. Congo’s musical CV is a great place to investigate the roots. Now in his fifth decade as an active musician, his work maps out some of the most important parameters of the movement and takes us back to the earliest seedlings.

“All these years jungle has been the tortoise. We’ve held our position while others have been the hare, rushing around from here to there. This story could have been told 30 years ago, but no one wanted to print it...”

Prior to changing his name to Mikail Tafari in 1994 in accordance with his faith, Congo was born Michael West in 1965. A child of Windrush, his grandfather moved his father’s family from Trench Town, Kingston. “Little did he know,” ponders Congo wryly, “that Tottenham was going to be a crack hotspot and gangland ends which his grandchildren would grow into...”

Home to other luminaries and pioneers such as the Demon Boyz, Terry T, Paul Ibiza, Kemet Records’ Mark X and 3rd Party Records’ James Stephens, Tottenham’s Broadwater Farm estate was a pressure cooker throughout the 1980s; Riots, racial tension, right-wing government, high levels of unemployment, police brutality. “Jungle. That’s what we called the place,” he recalls. “As a youthdem, that’s where you’re going because the bigger mandem and the rudeboys are there. Everyone is over the Farm. That was our spot.

“It was the beginnings of it all. Man brocking into yard. Capturing it for two weeks. Make sure it’s clean. Change locks, print flyers. That’s how we started. We had nowhere to play. We couldn’t get into no clubs. Black youth in Tottenham? You couldn’t get into clubs! ‘Sorry lads, blazers tonight’.”

Congo and his friends built their first soundsystem around this time. The Ital Sound would herald every conscious record they could get their hands on as both reggae and hip-hop provided new benchmarks for Black youths, showing them a route out of the economic and concrete jungle. It wasn’t long before he was mapping his own route. After a brief experiment under aliases such as Micron and Micski he settled for Rebel MC and swiftly experienced chart success as an early UK MC. Collaborating with Double Trouble (a duo comprising UK garage pioneer Karl ‘Tuff Enuff’ Brown and Michael Menson, who was sadly killed in 1997), ‘Street Tuff’ heralded Rebel’s arrival, leading to a hit that scored No. 3 in the UK Top 40 and charted highly across Europe.

Explorations of identity and environment were key lyrical signatures from the very beginning for Rebel MC, as tracks like ‘Cockney Rhythm’ captured him relishing in the UK melting pot. His 1990 debut album ‘Rebel Music’ followed, a fizzy collage of acid house, UK hip-hop, pop and soundsystem culture held together with breaks, reggae samples and social observations.

“The underground sound. The Jamaican sound. The fusion,” he lists. “It was so crucial. This fusion between London youths and their Jamaican heritage, putting on their own dances, pressing their own tunes. Their own ecosystem and culture. Wailers did that for us. Reggae did that for us. It was the first music that came along and said, ‘I’m going to be the boss, we’re not searching for a boss, we’re the boss, seen?’”

1991-92 saw Rebel dropping two more albums. ‘Black Meaning Good’ hit hard with its messages about police brutality and institutional racism. A rising tempo, political samples and more hooks and beats sampled from reggae, it was heavily political. By his third album ‘Word, Sound & Power’, Rebel was effectively planting proto-jungle seeds as fast-paced cuts like ‘Humanity’, ‘Rich Ah Getting Richer’ and ‘Jahovia’ pepper the album with up-tempo breaks, surging, urgent conscious messages and political observations. “But Rebel wasn’t getting a good time!” Congo exclaims. “The press had made up their mind. They weren’t getting I or seeing I! People had made assumptions. Congo could not exist alongside Rebel. I had to burn Rebel in the fire.”

A string of aliases rose from Rebel’s ashes, starting with the hardcore-focused X Project before he unleashed the iconic Conquering Lion alias with seminal cuts like ‘Inahsound’, ‘Lion Of Judah’ and ‘Code Red’. One of jungle’s earliest anthems, the latter is still drawn for to this day. Rebel sowed the seeds, Conquering Lion was part of one of the earliest harvests.

“It was a mystical harvest of unity,” he smiles warmly. “We were creating artistry, bringing in the vocal elements and voices. Jungle was being played in a reggae dance. We could play a jungle track in a reggae christening! All of a sudden jungle is being played by reggae man, hip-hop man. Unity.”

Unity remains at the core of jungle’s true code. As Congo describes, jungle music was like the real jungle: “No one animal rules. We work together. This was formed to smash down bullshit and cliques and monopolies and egos. It was a revolution.” But the revolution was stopped in its tracks. In late 1994/early 1995, as the first jungle crossover hits had really made an impact on the mainstream (notably M-Beat’s ‘Sweet Love’ and ‘Incredible’ and Shy FX and UK Apache’s ‘Original Nuttah’) and it became a youth phenomenon beyond London, jungle was already being declared dead. “Everything got twisted!” spits Congo. “The media saying ‘jungle is dead. It’s crackheads. It’s violence. It’s this, it’s that.’ Man put a block on it!

“All the shops tried to refuse jungle,” continues Congo, who famously linked exclusively with Nicky Blackmarket to sell Congo Natty releases. During the mid-‘90s, if you wanted records by any of Congo’s multiple aliases (Blackstar, Lion Of Judah, Tribe Of Issachar) then you could only get them from Nicky in his Soho store. “I pushed everything through one shop. No one could tell me nothing, no one could get no dubplates from me. No tunes from me. You have to go through Nicky. Seen? Why did it work that way? Because Nicky showed the most love to jungle.”

Love is a key word. Congo states that “jungle is love” at various points during every conversation. It means purity of intention; no ego, community-minded, creation for the sake of creation, making music because you believe in it and treating it as a discipline. Living and breathing it like a samurai; that’s the true spirit of junglism.

“What makes a revolution? A circle. So when the circle fulfils, it completes that revolution. For us, that is our children. You know a junglist by the fruits they bear. Nanci & Phoebe completed the circle. Nia Archives completed the circle”

In the contemporary context of ‘Ancestorz’ he applied this mindset to make what he calls “pure music”. A blessing from lockdown, the last two years have provided a unique moment in time for Congo to dive far, far deeper into the creative process than the normal industry practices typically allow. Due to jungle’s treatment over the years, no matter how much of a pioneer he has been, and how much he’s contributed to UK culture, his life has been forever on the road and in the trenches, rolling from gig to gig. Under no other circumstances could he have had the space to weave a 25-track album together so tightly, with so many cameos and samples from artists around the world — São Paulo’s Monkey Jhayam rapping in Portuguese, Joe Fareast rapping in Japanese, spoken words and stories from every continent of indigenous people from India to Native America. The last two years gave him time to tell the story he was scratching the surface of on his 2013 album ‘Jungle Revolution’ and has effectively wanted to tell since the days of ‘Black Meaning Good’.

Zoom out for the context of jungle over the last 30 years, and this sense of love, diligence and persistence is found purely in the fact that Congo has insisted on his craft, despite hardships or lack of support from the media, venues and the wider, much more commercial drum & bass scene which jungle gave root to. Congo is not a fan of the commercial side of drum & bass and describes it as “compromised, distorted and dumbed down”. The irony that an unauthorised edit of his most famous song has become a highly sought-after unreleased track in recent d&b years is not lost on him. The 1996 Tribe Of Issachar release with Peter Bouncer ‘I’m A Junglist’ was written as a direct shot at those who decried the scene and fair-weather junglists. “When jungle went through sufferation, where were all the junglists?” asks Congo. “Why do you think that song come out in ’96?”

Weak, strong, right, wrong; fundamentally this is a story about a junglistic man who has fought for the artform since day one and risen above enough wicked plans to see a whole new generation empowered by the music. The significance of this is vital to Congo and something he’s been encouraging since he signed the Brixton duo Nanci & Phoebe to his label back in 2012 with the evergreen track ‘Notorious’. “What makes a revolution? A circle,” considers Congo. “So when the circle fulfils, it completes that revolution. For us, that is our children. You know a junglist by the fruits they bear. Nanci & Phoebe completed the circle. Nia Archives completed the circle.”

It’s no surprise all of Congo’s children have all completed the circle. As well as his aforementioned daughters Kaya and Lydia, he also has two sons: Congo Dubz, who DJs with him regularly, and hip-hop/drill producer Yoz Beatz, who’s produced for prominent rappers like Pop Smoke, Fivio Foreign and Fredo. “Children of jungle!” Congo smiles, before explaining how Kaya and Nicky Blackmarket’s daughter Millz are echoing their own fathers’ histories and linking up to collaborate. The circles continue to revolve.

Now, having written the album he’s always wanted to write, and still not committing to tours and gigs like he was pre-Covid, Congo has two new ambitious missions: to inspire and help establish a new culture within jungle that’s based around supporting both the new generation and those who are affected by mental health and financial issues, but still play the best performances of their lives multiple times a week. “Soldiers are soldiers, they go into the battlefield and the crowd don’t know that!” he exclaims. “They don’t need to know that because for that moment you’re a billionaire. Everything is criss. You can be who you want to be. You’re in that moment. But that moment is over when you return to your yard.”

A new label, Rekovery Records, is the first part of this new revolution for Congo. He explains how the label is dedicated to music and frequencies that heal, soothing souls in a currently savage world that’s rife with some of the most greedy, self-serving capitalist tactics humankind has seen in generations.

“It’s vital that we put each other first and set that example,” he says as we sign out. “Youths have been shown the opposite. Put in the least, get the most. Push over your bredrin to get first place. Everyone’s got to be first, but jungle was never a first-place music. It’s a circle. Vibration. No ego. And for this to continue we need to do as much as we can for the youth and make our platform their platform and let them know that you can have love in your heart. You don’t have to be a shark. Just love. Reggae is love. Jungle is love.”

The jungle revolution continues. And this time, thanks to pioneers and originators like Congo Natty, it’s free to flourish and the story will be told properly and fully.