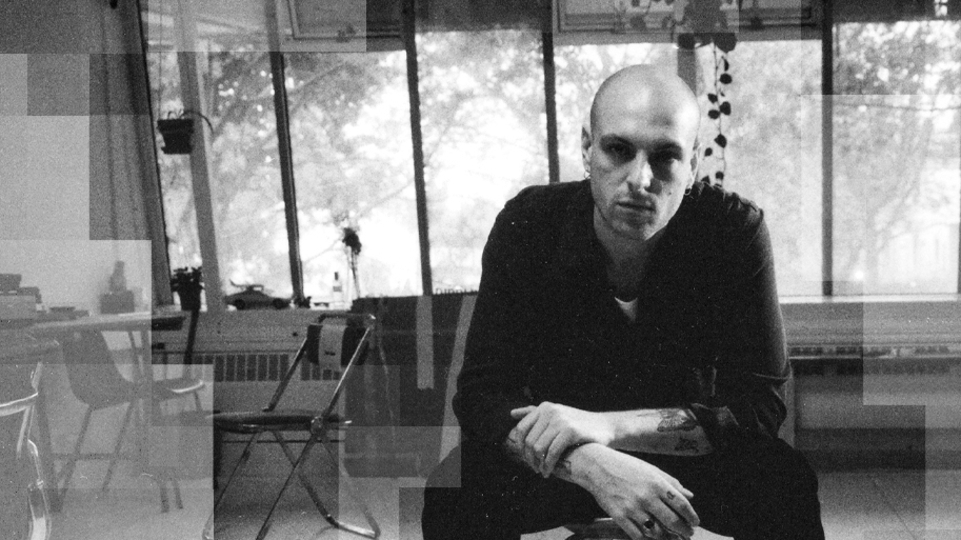

On Cue: Leon Vynehall

Leon Vynehall sculpts a mix of experimental sounds, smoky house and peak-time techno for the On Cue series, and speaks to Ray Philp about finding his place in the landscape of electronic music, and his most ambitious release to date, ‘Rare, Forever’

One balmy evening 18 months ago, Leon Vynehall went to a Kano gig and realised he was stuck. Watching the grime pioneer perform at a sold-out Royal Albert Hall, Vynehall was awestruck by the sight of an artist “speaking his truth”; it was a symbolic capstone for a scene historically sidelined by the press and sometimes persecuted by the London Metropolitan Police.

With the exception of 1Xtra’s Grime Symphony in 2015, the 150-year-old venue hadn’t seen a show like it — sousaphone players duelled with classic grime riffs and, as Vynehall puts it, people were going berserk. The show left Vynehall full of admiration for Kano — and full of doubts about himself. “Even now I get goosebumps thinking about it, it really moved me,” he says. “I felt honoured to be there, to hear him say those things. And I just thought to myself, ‘What am I trying to say?’”

Vynehall felt adrift, and probably depleted. In the year prior he’d released ‘Nothing Is Still’, a widely acclaimed debut album on Ninja Tune, accompanied by music videos and a novella co-written with Max Sztyber. The ‘DJ-Kicks’ mix that followed a few months later convincingly captured Vynehall’s expansive DJing, with tracks from Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Haruomi Hosono, UK street soul group The Bygraves, and experimental US composer Ellen Fullman. Coming from a DJ and producer whose work has frequently gestured to his interests outside of dance music, this year-long stretch of public activity saw Vynehall at the height of his creative powers. But by the time he’d turned 30, a birthday he celebrated in Los Angeles’ bohemian paradise, Laurel Canyon — surrounded by trees and hillsides, he stayed with friends “in a house I could only imagine being in one of David Hockney’s paintings” — his thinking went more or less like, ‘What now?’

His new album, ‘Rare, Forever’, is inspired by that absence of inspiration, and what it takes to find it again. When he got back into the studio, “My first thought was, ‘I’m going to reject the idea of story’,” he says, a condition he’d imposed on ‘Nothing Is Still’. “I was like, this time I don’t want to do that — I’m going to turn on a machine, pick up an instrument, or find something and follow that idea through the fog.”

He also became interested in abstract painting around this time. “I was in love with this idea of letting the work tell you what to do in a more abstract way — like a painter would do one brushstroke, or dip a colour, and then think, ‘Where am I going to go from here?’ without actually having a plan.”

The appeal of ‘Rare, Forever’ partly rests on its familiarity. Songs like ‘Worm (& Closer & Closer)’ and ‘Alichea Vella Amor’ are flush with the mellow warmth that runs through all his records; a lived-in feel that you’d also find on, say, Mark Farina’s ‘Mushroom Jazz’ series, where soul, hip-hop, house, and acid jazz rub along easily. But if that warmth was only the sum of a tasteful record collection, his music wouldn’t strike such a consistently powerful chord.

Take 2014’s ‘Inside The Deku Tree’, a reference to ‘The Legend Of Zelda’, which sometimes gave you a glimpse into a world of private emotion made richer for its seclusion. This feeling was fleeting at first, but as his music matured beyond the 12-inch format, Vynehall found ways to express themes like memory and intimacy with greater depth. If what we hear in Vynehall’s music are echoes of his past, they somehow seemed like echoes of ours, too.

Nearly 100 years ago, the founder of surrealism André Breton wrote a manifesto explaining that he wanted to set aside rational thinking and let the subconscious do the work. In taking a similar approach for ‘Rare, Forever’, Vynehall found that his inner self was all over the shop. “I sounded like a confused man,” he says, remembering the first time he’d listened back to the album when he thought he’d finished it.

“I was throwing the kitchen sink at it because I was trying to prove to an audience that I could do whatever I wanted. I thought that people just thought I was this dance music producer — which is not a bad thing in itself — but it’s not what I saw myself as,” he continues. “I remember silly things like getting email notifications from Spotify telling me that my music had been added to an ambient playlist, or a playlist for people when they’re studying. It weirdly bent me out of shape.”

You might hear this fraught state of mind on tracks like ‘Snakeskin ∞ Has-Been’, one of the few that survived the first draft. ‘Snakeskin ∞ Has-Been’ runs quickly through see-sawing glissandos, sticky vocal textures, and a needling breakdown. “It’s quite a violent song, actually,” he says, “it dips in and out and flutters around; it was how I was feeling at the time.” But as Vynehall pushed on he began to ease up, and the results made for some of his subtlest work.

‘Farewell! Magnus Gabbro’, where two oscillating organs grind out a hymnal drone, is an unexpected echo of Andy Stott. ‘Ecce! Ego!’, whose sax lines and symphonic strings curl and drift amid bruising synth leads, shows a greater willingness to set pretty ideas in an ugly frame. And his club music — from the kickless trance of ‘An Exhale’ to the tight UK funky syncopations of ‘Dumbo’ — seems sharper for no longer being the focus of what he does.

Vynehall has had other anxieties besides the creative process. Over the years he’s developed as a solo artist in the truest sense; aside from two remixes for Midland and The Juan Maclean early in his career, he has little clear affiliation with other artists. While Vynehall’s music has the sort of wide appeal that could draw comparisons with Four Tet or Floating Points, he isn’t someone at the tip of a larger scene or involved in high-profile collaborations. If you’re an artist looking to avoid confinement in the dreaded pigeon- hole, this might sound ideal — but it began to bother Vynehall.

“One of the things I had to wrestle with when I started making this album — and perhaps one of the things that put me into a mental tailspin — was thinking, ‘I don’t actually belong anywhere’. For a long time, I felt quite sad about that; like I had no place in the landscape of electronic music.”

This musical isolation he felt is connected to what Vynehall says can be a “crippling” imposter syndrome; he’s laughing when he describes himself as a “sad little bumblebee” without a hive, but the point might resonate with other artists who in the past year have struggled to be creative, or have seen their mental health suffer. To Vynehall, making music is “like a form of therapy”, he says. “It keeps me sane. I still don’t think I know who I am fully, but that’s the whole point of this record — it’s an ongoing process. I change. We all change.”

If his public persona has become a solitary creation — one that he no longer minds — his private one is full of company. Vynehall live-streamed a gig of his last December, titled A Little More Liquid, which was “really fun to put together”, he says. “There was a basement section where I played live, then I moved up a corridor and played ‘Farewell! Magnus Gabbro’ with Amy Langley, who plays cello and who I do all my string arrangements with; down a long hallway, I played ‘Alichea Vella Amor’ with a sax player called Michael Underwood.”

Other friends and collaborators Vynehall admires — Blue May, who mixed ‘Nothing Is Still’ and directed the Kano show, or Ben Baptie, who mixed ‘Rare, Forever’ — are people he appreciates for their commitment to high standards, which has helped elevate his. “Where my younger self may have wanted to create things, but done them in a haphazard way, I’ve since met and collaborated with more people, and specifically people who don’t take any bullshit, and they do things properly. Someone asked me the other day, ‘What are the things that have influenced you?’ And they were expecting me to reel off some artist names. But it’s not — it’s my friends.”

Tracklist:

Jan Jelinek 'Lady Gaga, you once said in an interview that you write music for the fashion industry. Is fashion as important to you as music?'

Lack ‘Version’

Leon Vynehall ‘Poem Excerpt From "In>Pin"’

Meara O'Reilly ‘III.’

Fluxion ‘Outerside’

DJ Minx ‘A Walk In The Park (Minx's On The Slide Mix)’

Cabin Trax ‘Rainy Dayz’

Blaze Presents James Toney Jr. Project ‘Lovely Ones (Shelter Deep Vocal Mix)’

SE62 ‘Fear’

DJ SWISHA & Kush Jones ‘GTB (DJ SWISHA Remix)’

Bored Lord ‘Ugly Laugh’

Samuel. L ‘Untitled B2’

Sockethead ‘West’

Pavilion ‘Green Spirit PM’

DJ Plead ‘Liquify’

Thanos Hana ‘Pointy Head’

TYGAPAW ‘Run 2 U’

Blawan ‘Immulsion (That Kind Of Kink Mix)’

M. Schaffhäuser ‘6 UHR MORGENS (JD Twitch Unreleased Edit)’

Stephan Mathieu ‘Variation Zwei’

Excerpt from BBC Documentary "6 Days In September" with John Hoyland

Loscil ‘Stave Peak’

Leon Vynehall ‘Alichea Vella Amor’

Meara O'Reilly ‘II.'