A day in the life of Alok

DJ Mag spends some time with the Brazilian DJ sensation while he’s over in London for a show at Ministry Of Sound, and learns about his journey from hardships to huge success — and how being in a plane crash changed his perspective on life for the better

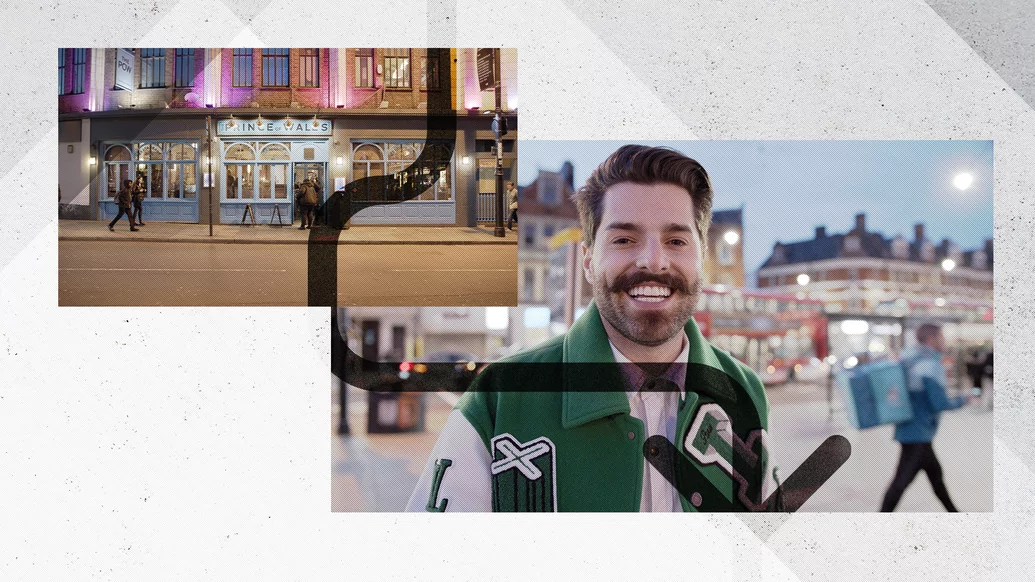

Purple and pink hues stretch across the London skyline as the first stars tattoo themselves above the landscape. Outside the Ritzy cinema in Brixton, South London, young skateboarders perform tricks, skating atop handrails and skidding across surfaces while being filmed on a VHS camera. Brazilian DJ and record producer Alok is trying to perform a skate trick. He attempts it once, twice, and on the final try, just about manages to land it. Grinning, he hands the board back to the young person and walks away. “It’s called ‘The Impossible’,” he says. “The first time I heard of it, I knew I wanted to master it, so I did, but now, I don’t have much time to skateboard.”

This is Alok, the 30-year-old DJ and producer who hails from Brazil: a laser-focused, energetic individual who sets his sights on achieving his goals and ensuring that he never falls short. He always likes to be in control of his schedule: his days are meticulous and precise, nothing out of place, every cog in the machine moving towards the result he wants to achieve. It’s how he released 42 songs last year and has garnered 27 million Instagram followers, why he’s able to perform night after night on a sold-out world tour and run a record label, and manages to find time to do his charity work. Add to that having two toddlers and a social life, and it may appear Alok barely has any time. Yet, he is a humble, caring individual whose focus is always on the present. It may sound tiring being Alok, but he wouldn’t change anything.

“I can never complain about this,” he says, sitting in The Prince Of Wales, a pub in Brixton. “I’m not someone that had everything. I never had stuff.” Twelve years ago, while studying in London, Alok used to work at this very same pub. He would commute an hour from university to work here, finish a shift and take a two-hour night bus home to deep north-east London. He moved to the UK when he was 18 to study English and become a DJ in one of the world’s foremost cultural capitals. Handing out his CV to multiple places, he was rejected from many clubs and was unable to even secure a job because several places said he didn’t speak English well.

Tonight, though, Alok is performing at the one club he used to diligently ask to play at when he was 18. Now, he has sold out the 1,600-capacity Ministry Of Sound in less than 24 hours and boasts regular festival headliner slots at the likes of Tomorrowland, as well as being voted No.4 in DJ Mag’s Top 100 DJs poll, the highest position ever occupied by a Brazilian. “It was so hard in London,” he says. “I looked around me [in Brazil], at all the artists, like my parents, and there were financial problems. I said, ‘I don’t want this for me’. My dad said, ‘If I had your talents, I would be flying’. In that moment, I realised I needed to give it one more chance. Then, things just started to happen.”

Nearly 30 years ago, the first domino fell. Brazilian DJ Ekanta was living in an abandoned hospital in the Netherlands, working as a cleaner at a psy-trance club. Introduced to the genre and DJing by her husband, DJ Swarup, they took their knowledge back to their home country, where they became renowned for being pioneers of psy-trance in Brazil and creators of a music festival in Bahia, Universo Paralello. They also passed on their knowledge to their sons and fraternal twins, Bhaskar and Alok.

The twins would learn several different instruments in their early childhood, before learning to DJ at 10, starting their careers at 12, and learning to remix tunes, eventually creating their first project, Logica. “My parents never wanted me to DJ,” Alok says. “They wanted me to study, go to university, because they always said it was very hard to live through art. But I saw in them a kind of inspiration. Once we started producing, it was just natural.”

Embarking on a solo career at the age of 18, Alok ventured to London, hoping to find success there. After a year of hardship and being shut out from clubs, he moved back to Brazil, where everything started falling into place. “I think it’s really how much I changed my perspective about what I wanted and where I wanted to go,” he says in the car, zipping around London. “I was always very much inside a box. The way we judge the world, the way we think the world would judge us. As soon as I stopped with these judgements that gave me a prison, I started to be free.”

With this newfound attitude, Alok went into producing regularly. He became obsessed with a newfound genre called Brazilian bass, which emerged in the early 2010s as a deviation from mainstream deep house. Fusing elements of tech-house with minimalistic influences from bass house, Brazilian bass is notable for its distinguishable deep, punchy basslines. Alok’s 2016 smash hit ‘Hear Me Now’, featuring the Brazilian-American recording artist Zeeba, took the genre global. The music video for the song has over 422 million views on YouTube alone.

He quickly became one of Brazil’s biggest musicians, arguably its biggest pop star, and became friends with the likes of footballer Neymar Jr., performing at his world-renowned birthday parties. Collaborations with the likes of Armin van Buuren, Timmy Trumpet and Steve Aoki followed, while he was booked to perform at major festivals like Lollapalooza, Coachella, and Tomorrowland, and sold out shows regularly around the world. He garnered fans everywhere, from Israel to Romania to Chile, India and New Zealand. His star was on the rise. Fans, too, flocked to his music, finding it aspirational.

"Now, I believe success is very subjective. We cannot put it into a formula. Now, I want to donate more to help people”

“His music touches my soul,” Daniel from Russia says, a few minutes after meeting Alok in the DJ Mag offices. “I always listen to it when I’m in a bad mood, as he rescues me.” Leticia echoes him, stating, “Every time we listen to his music, good memories come in my head, whether it’s traveling with friends or on the beach, it’s always like we’re having good moments.”

As Alok dealt with this newfound success and fame, his world came to a sudden halt in 2018. A private plane he had chartered at Serrinha airport in Juiz de Fora, Brazil on Sunday 20th May crashed after takeoff. Nine people on board, including the pilot and co-pilot, were thankfully not injured. It was claimed that as the end of the runway approached, the plane failed to take off, leading to the craft falling into a ravine; footage taken by vehicles out on the road showed the plane at a precarious angle.

“I knew I was going to die. I was sure of it,” he says, stopping to take out his phone to show everyone in the car pictures and videos of the incident. “The plane stopping was a miracle. I had it in my mind that if I died that day, at least I knew if I hadn’t achieved all my aims, I was doing it the right way. At that moment, I realised how tomorrow doesn’t exist. Every day, I am just so grateful for being here. I now celebrate my reincarnation on 20th May every year.”

A year later, Alok married his partner, Romana Novais, and had two children within 18 months of one another. He also dived deeper into his charity work, which he had started when he was 24, but is shy to inform audiences of in interviews. “I was very depressed with life then,” he admits. “I was always asking what happened after death, and what was the meaning of life? People told me that success in life was to get money and fame. I felt so empty, so confused and depressed.”

To clear his mind, he went deep into the Amazon, spending countless hours on a bus and then a boat to meet indigenous tribes. He spent 10 days there, before a friend took him to Mozambique. His friend was working with 600 children there on various humanitarian projects. These trips inspired Alok. He encountered individuals who shaped his worldview, teaching him how to be happy, to appreciate his life. “I felt I was the biggest, most miserable person,” he says. “They were way more connected to God and nature and each other. I had everything, and I was complaining. From then on, I knew I couldn’t change the world, but I could change one person’s world.”

Alok decided to start taking a portion of his earnings, donating it to those less privileged than him. In Mozambique alone, the number of children his friend helps went from 600 to 20,000 in six years, thanks to investment from Alok. He single-handedly ensured an elderly woman he met the first time he was in Mozambique, who tied her stomach tighter every day with a belt to subdue her hunger, would be fed every day. He paid for her cataract surgery, which enabled her to see again, and helped her family alleviate themselves from poverty. “I never want to go back again to that place of depression,” he says. “If you asked me seven years ago, ‘what is success?’ I’d say, ‘buy a Ferrari’. If you said ‘philanthropy’, I would say ‘shut up’. Now, I believe success is very subjective. We cannot put it into a formula. Now, I want to donate more to help people.”

One of the ways Alok did that was when he became a character on Garena Free Fire, a battle royale game. It was the most downloaded mobile game globally in 2019, mostly in emerging markets like Brazil and India. As of 2021, it had grossed more than $4bn worldwide, and Alok’s character was the most downloaded character of all time. Alok donated 100% of his profits to charities in India, Brazil, Mozambique, Madagascar and Malawi. He’s coy to reveal the exact dollar amount, but it’s somewhere in the millions.

While doing all of this charity work, Alok also had a relentless release schedule, with 42 of his singles coming out in 2021 alone. “I did that because we were in the pandemic,” he reveals. “I had to put it out. That’s not something that I’m going to keep doing. I was confused, my fans were confused, ‘why is he putting out so much music?’”

As he stares out the window contemplating this last thought, he turns back to say something that’s been on his mind. “People expect me to be only electronic,” he says. “I feel what brought me here is not necessarily what I am in your head. My creativity tells me to do something, even though that doesn’t fit with the formula. I am always challenging myself in every way, from my production to my next goals.”

Is there an EP or album in the works then? “Maybe,” Alok says shyly. “I have a very special project coming. It’s not for myself, it’s for a different reason. Last year, I was asking myself, ‘where is the future?’ We always had a mindset that the future would be all flying cars, where everything is neon. Then, I thought, ‘why can’t the future be indigenous in small boats in the middle of the Amazon?’ I’m gonna do something like that. It’s called ‘the future is ancestral’.”

With ambitious plans to record indigenous tribes throughout Brazil and get them onto an album, Alok aims that his work there will allow people to see the destruction of the Amazon. “We are saying that we have to protect the forest,” he says, “but we first have to listen to what the forest has to say, because we don’t understand it. The best way to translate what the forest is saying is through the indigenous songs, because you don’t have to understand the language to feel it.”

Alok’s excitement starts to quieten as the car zips through central London on the way back to his hotel. Silence hangs in the air. Alok is getting tired. He’s been awake since 7am, traversing through the city on a warm, busy Saturday with a packed itinerary. We’ve visited three different boroughs in West, East and South London, and only eaten once. He needs to rest. Ministry Of Sound beckons, a performance he’s been looking forward to for more than a decade, and he still hasn’t prepared his three-hour set yet.

As he exits the car to the hotel, he stops, as he’s noticed a group of people. He turns to greet them and hugs each one, taking the time to speak to them individually, before taking a group picture. They’re all fans who have been waiting outside his hotel for hours. Unable to make it to his show, they wanted to catch a sight of him nonetheless. Despite having been on the road for more than 12 hours, Alok is happy to speak to them, giving them more than just a few minutes of his time, and urging everyone else inside while he’s deep in conversation.

Finally, he walks back into the hotel and readies himself for the show at the Ministry Of Sound. Later that night, as the lights explode at the first bass drop, a smile stretches across his face, as he sees the crowd’s reception to his music. Twelve years ago, he couldn’t get in the door. Now, Alok is playing to a crowd of devout fans, eager to devour his music. This feels pre-destined, like a journey of hardship he had to embark on to land up here, where he was meant to be, back in the city where he faced his toughest test in life. “I’m grateful every day,” he says softly.