Deena Abdelwahed: forging futurism from tradition

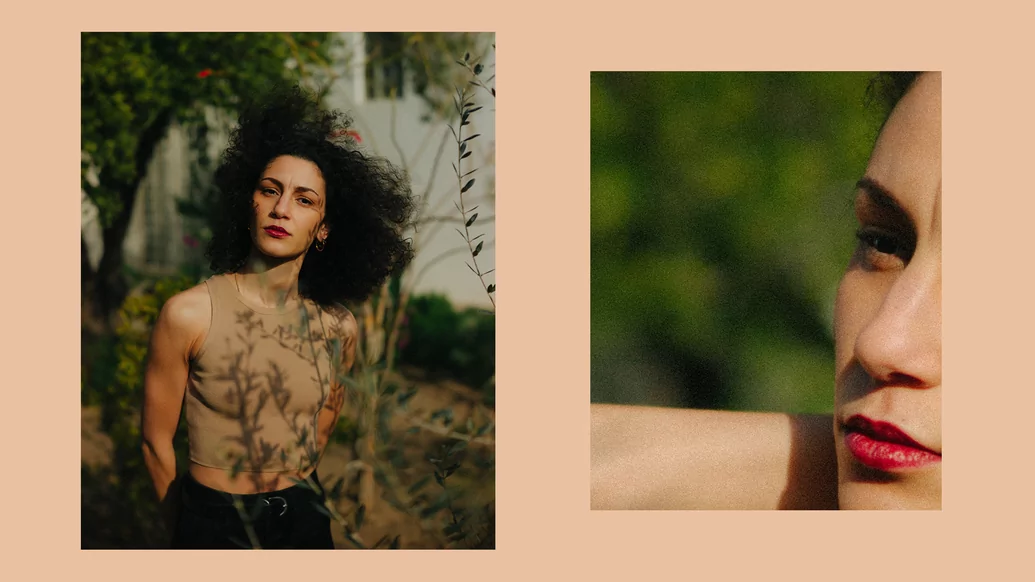

With her new album ‘Jbal Rrsas’, Deena Abdelwahed pioneers new forms of electronic music shaped by musical traditions from across the Arab world. Here, she speaks to Martin Guttridge-Hewitt about studying regional dance music styles, the nature of collaboration, and opening minds to new possibilities

“With my first album, I wanted to do what I did today with ‘Jbal Rrsas’. But I knew I wasn’t capable enough. I wasn’t confident enough. I had to study more. And, especially, I think back then people were not ready. It was not the same as now.” DJ Mag has been on the phone with Deena Abdelwahed for 20 minutes, and one thing is clear. The Paris-based electronic polymath, of Tunisian descent and Qatari upbringing, contrasts dense, intellectual musical output with straightforward answers and refreshing honesty — happy to discuss the limitations and accomplishments of her work.

Landing on French institution InFiné Music, the producer’s second long-form release, ‘Jbal Rrsas’, is a visceral, mutant body of work. Opening on the apocalyptic horns and tension of ‘The Key To The Exit’, it immerses you in a world of live-sounding drums and harmonies cast in the timbre of experimental rave, honours shared with synths plucked from industrial and bass cultures. Diverse yet coherent, it was made with a singular goal in mind.

“Dance music styles in the Arab world, that are still folkloric, percussive, where you only have the groove if you use samples from actual percussionists — how can I do that in a synthesised way, without it feeling experimental, artyfarty, avant-garde, whatever? How can we make it organic, close to the people? For me, that’s the biggest challenge,” says Abdelwahed, revealing ambitions to take foundations laid by her inaugural LP, ‘Khonnar’, where Arabic tones met UK and European electronic blueprints, and this time make “the skeleton”, the core musical structures, entirely “from the Arab world”.

“I was mainly focused on playing with the laws of Arabic music, rhythmically and melodically,” she replies when asked if the new album has overarching themes like 2018’s debut, which touched on subjects like identity and gender. “The idea was to make something that puts no region over another region. A specificity, rhythmically or melodically, from each country, put into each track. Mainly dance, traditional dance music, from that place. So I’m not using academic or classical music [from] these countries. I’m using my research based on their dance music.” This focus is understandable when we consider Abdelwahed’s journey so far.

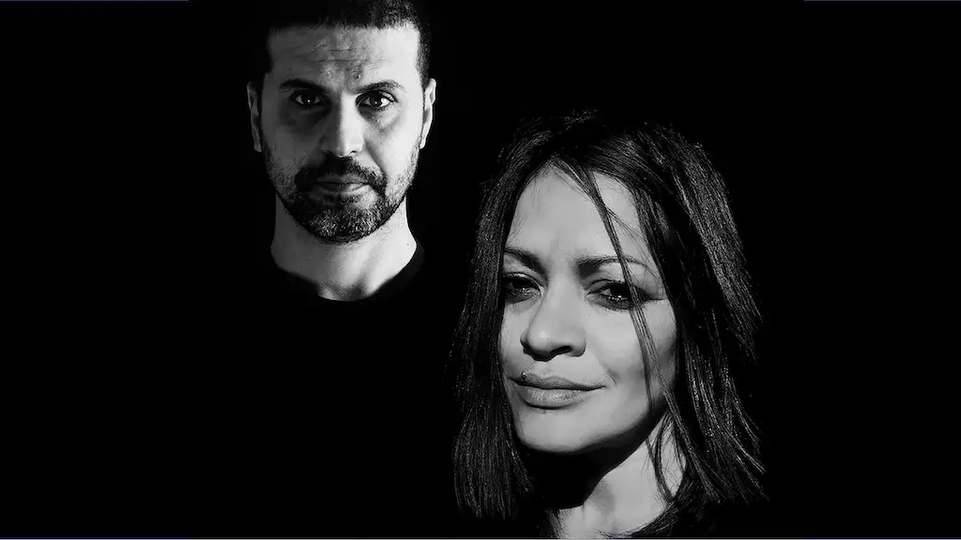

“What does it mean: collaborator? I think collaboration here was really just me doing a thing, then calling Khalil and saying, ‘Please, listen to it. Tell me, is it correct? Is it not correct?’”

Casting her mind back to moving from Doha to study at the Institut Supérieur de Beaux Arts de Tunis after turning 18, circa 2008, she is candid about the relocation. To her, music, dance and exhibitions were more “part of living culture, daily life” in the North African city, as opposed to the grand orchestrations commonplace where she grew up. In turn, practitioners were “more exposed to change... more open-minded”. Abdelwahed’s affinity with grassroots scenes and sounds is reflected even more vividly when she recounts b-boys and girls throwing down in Tunis branches of Maison des Jeunes et de la Culture, a French non-profit organisation running youth culture spaces, often in deprived areas.

This sowed seeds for her first great electronic music love, footwork. “For me it was something between the breakdancing I was watching, bass music I was hearing, and also the polyrhythms we have in dance music folklore traditions.” The idea of musical elements shared between disparate styles led to Abdelwahed’s first long-player, and the sounds therein. ‘Jbal Rrsas’ takes the next step. Explaining her belief that countries from Morocco to The Gulf region have yet to establish defined schools of electronic dance music production in the same way as her beloved bass developed — a term she applies to a family of genres including jungle and dubstep — in many ways the entire project could be considered an exercise in establishing a new electronic music language. One removed from the core canons established during the development of Western rave.

A huge endeavour, rough drafts of ideas for the record began to take form in 2019, and plenty of time during the pandemic was dedicated to conducting research into what makes up particular types of music, from rules of rhythm to hierarchies of instruments. The list of collaborators also speaks to a goal of achieving authenticity while forging something completely new. Namely, Tunisian composer and multi-instrumentalist Khalil Hentati, Iraqi-British musician and researcher, Khyam Allami, and Egyptian mastering engineer, Heba Kadry. Even the cover feeds into this, comprising an image of a mountain near Tunis (from which the album takes its title), taken by Abdelwahed and photographer-friend Yassine Meddeb, and rendered in subtly psychedelic hues courtesy of Niculin Barandun, who also creates visuals at live dates.

“What does it mean: collaborator? I think collaboration here was really just me doing a thing, then calling Khalil and saying, ‘Please, listen to it. Tell me, is it correct? Is it not correct?’ And they’d take the time to honestly come back to me and say ‘I don’t like this one’, or ‘It’s better if you put that there’,” Abdulwahed explains. Their work really began after Hentati approached Abdelwahed convinced “the world is now ready” to hear Arabic music made with electronic tools, previously considering this task too challenging for both musicians and audiences. “He asked if he could jump in with me, I was like, ‘Sure, please, help’, because he knows how it is. Me, I just know bass music... whatever is out today from Bristol, or whatever. He’s more broad.”

Recalling how she became involved with Allami, Abdelwahed explains they met around 2013, when he was living in Tunis for a couple of years. The pair quickly saw eye-to-eye, partied together, and a strong friendship developed. “He started to talk to me about the tools for tuning on Ableton or whatever DAW I’m using. He liked the first album, ‘Khonnar’, but said it was a pity I didn’t tune anything. I said I’d like to learn, but not just to say I touched the tuning. It needed a purpose, so he started to teach me.”

Results of these consultations can be heard in the captivating brew of region-specific genres on ‘Jbal Rrsas’. Crafted without the standard instruments that form their basis, Abdelwahed creates a modernist take on the original manifestations of styles like mezwed, a traditional North African pop based on scale rhythms you’d usually need three darbouka drummers for, Egyptian mahraganat, which Abdelwahed says “reminds me a bit of baile funk in Brazil”, and maqsoum, a rhyming derivative of baladi folk dance. “I’ve tackled, or opened up, some stuff I was super afraid of, that I thought the people would not like or understand,” Abdelwahed says, adding that live shows based on this new work have garnered memorable responses.

At The Hague’s Rewire festival, for instance, a Kuwaiti punter told her closing track ‘Pre Island’ was like khaliji — a sound specific to his country and neighbouring states like Bahrain. “He’s perplexed, and doesn’t know how to feel, can’t understand how the groove makes him dance like khaliji, which has organic percussion, but this isn’t sampled in the track,” she recalls. While much of our conversation has painted an evocative picture of who Abelwahed is, this is maybe the most apt comment: an artist determined to remix convention, forging futurism from tradition, looking for ears ready to listen and bodies ready to move.