DiY Sound System: why free parties were vital for the UK's '90s rave scene

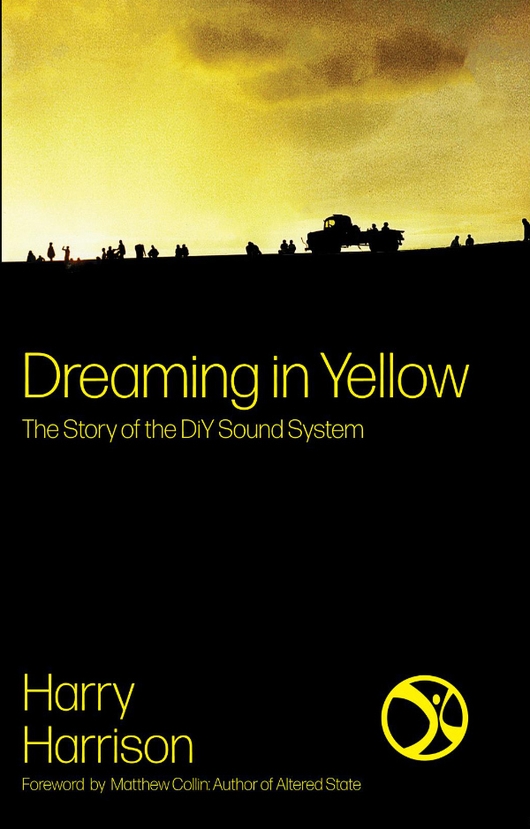

In the summer of 1989, DiY collective — one of the first house sound systems in the UK — emerged onto the rave scene. In this excerpt taken from founding member Harry Harrison's book, Dreaming in Yellow, he discusses DiY's role within that movement, and the importance of free parties during the '90s rave scene

Much has been written and debated over the years about just why the concept of a ‘free’ party was so important. Much more than simply the absence of an entrance cost, the ‘free’ prefix alluded to the whole history of alternative philosophies, a summary of events stretching back to pre-history where the constraints of a modern, regulated society did not apply. Resuscitated in the age of hippydom, ‘free festivals’ indicated liberation, temporary elusion from the binds of convention and commercialism. A ‘free party’ became so much more than simply a rave without a ticket price, it lay outside the legal reach of the police or the local authorities, it allowed individuals to trade for no profit and permitted them to interact in a radical collectivist way, wandering through fields at dawn with time to really talk. In the many debates over what constituted the first real free party, some have suggested conventional club nights or events for which no payment was demanded but I think that this is perhaps to miss the point; such an event may be free of charge but still fits within the infrastructure of four walls, security, licensing laws or a two o’clock finish.

However one defines a free party, we were definitely now doing them regularly and had all the ingredients necessary to continue, which we did with relish. For the remainder of the summer of 1991, we were aware of free festivals happening across the south of England but decided we preferred to party in Derbyshire; we few, we happy few, we band of brothers and sisters. On reflection, Moreton Lighthouse had spiralled so out of control and freaked so many people out that big festivals began to feel more like growing collective madness where there was a strong possibility of either getting mugged or arrested, where vehicles and sound systems might get trashed or impounded and, worst of all, the party might not happen. Over the next few months, free festivals occurred in Bala (Happy Daze), Cornwall (White Goddess), Hampshire (Torpedo Town) and big free parties mushroomed across London, mostly featuring Spiral Tribe and Bedlam, the two best known of the emerging techno free party rigs. DiY, however, were locked into our own growing scene, it just felt incredibly special and fresh, getting away with parties every weekend and relieved not to have to book another Luton van and head south with all our kit into unknown madness. Driving through police roadblocks had undeniably been fun but I’d rather not have to do it every weekend. That was until we took a call from Dangerous Dave, informing us that the Free Party People had discovered a choice site near Wedmore in Somerset and would we like to bring Black Box and DJ’s down over the bank holiday weekend? Well, yes, of course we would.

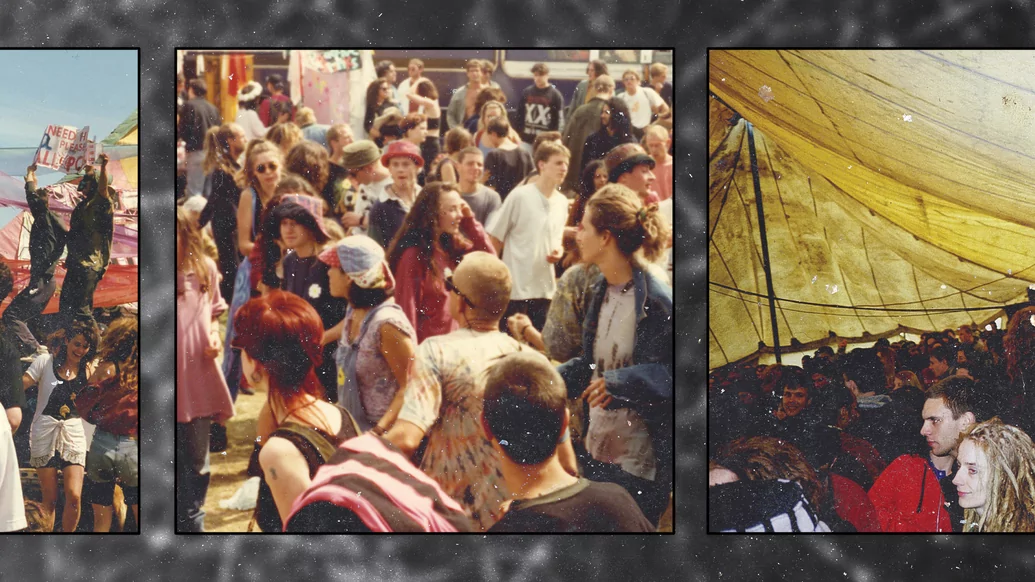

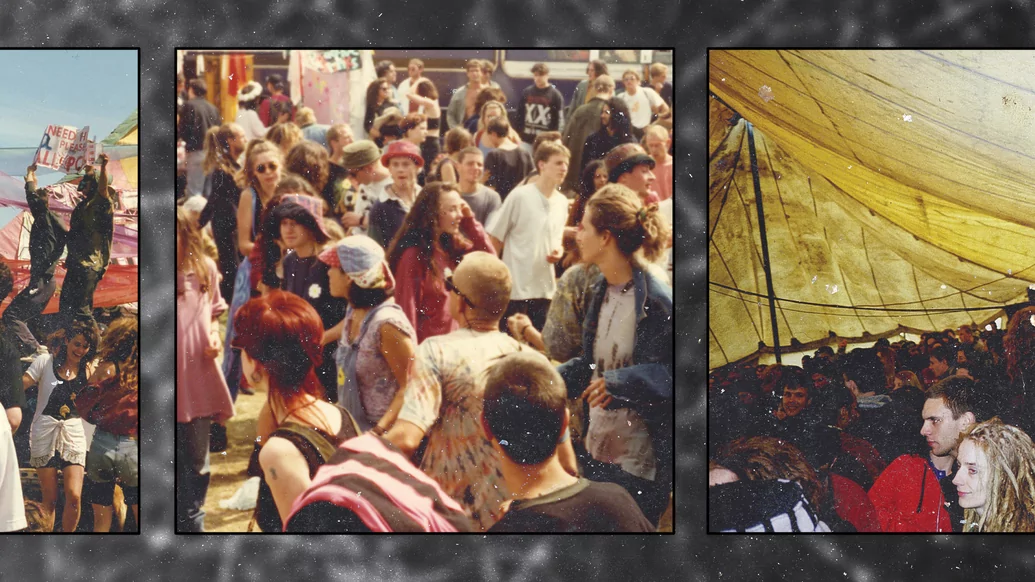

Held over the long weekend of the last Saturday in August, 1991, the Wedmore party was probably the most archetypal and classic free party we ever did. As ever, the FPP had done a fabulous job on the infrastructure. A perfect marquee was in place when my carload arrived on the Saturday evening, again with tank nettings, backdrops and endless banners flying in the glorious Somerset sun. A truly amazing lightshow was in place thanks to Dave and Moffball, Rob would bring more, there may even have been a laser. There was still a real innocence to free parties at that point, it all seemed so full of possibility and beauty and, as with all innovative scenes, it truly felt like this would go on forever. Who could not love this synthesis of house music, ecstasy and the timeless wonder of the English countryside. As I recall, Jack and Simon had arrived ready to DJ. I watched in awe as Dave wrestled a malfunctioning generator, in flames, to the floor before it kicked itself out of his grip and jumped insanely across the grass, for all the world like a petrol-driven bronco spitting fire, which explained clearly to me how he had earned the soubriquet ‘Dangerous’.

In those halcyon days we always seemed to have the gods, the old ones, behind us and soon another generator was found. Everything ready for the perfect rave except one thing. The Luton van, driven by Rick and containing our somewhat essential sound system, was nowhere to be seen.

People hugged endlessly; hugged friends, hugged strangers, hugged trees and sometimes tried to hug the police. With the benefit of age and hindsight, it may have been somewhat naïve and chemically artificial almost but by god, it felt good at the time

Again, being long before the days of mobile phones, we had no way of knowing what had happened, and so we waited. What had happened, and by now we really should have learnt to avoid Luton vans, was that Rick had taken a bend way too quickly somewhere on the A50 and turned the hire van over, it rolling some distance before coming to a halt on its side. In the back were not only a couple of tonnes of speaker cabs, amps and decks but also several human beings. I think in the end, mercifully only Phil and Rob were in the back and they emerged shaken and mostly unharmed. The really lucky thing is that our friend Tamsin and her young daughter Jelly had been planning to also sit in the rear box but cancelled at the last minute. Thank the Lord. Incredibly, the AA sent a tow truck which managed to pull the van back onto four wheels, they all climbed in again and Rick drove the van on to the party, arriving to a hero’s welcome. Now, that’s dedication to the cause. I also made a mental note that we really needed to get our own truck.

With the last element in place, the party commenced and rocked on until Sunday evening with no interference from the police. Perhaps the miracle of the PA truck had given everyone an extra spiritual lift and parties always seemed wilder in the sun, but this was a truly glorious night and day. People had climbed onto every available space, the speakers, buses, lighting platforms; anywhere to dance. And how we danced, devoid of ennui or the exhausted cynicism that inevitably affect movements like this eventually; danced like untamed pagans, which is pretty much what we were. This was also the zenith of what became known as ‘high tunes’, joyous, anthemic tracks that were just perfect for days like this. I have an abiding memory of Simon dropping ‘Everybody’s Free’ by Rozalla, with its huge opening strings, elegiac vocals and big, dirty rhythms at some point on Sunday morning and the place just erupted. At parties such as these we were collectively so high, in every way possible, and so blissfully, almost religiously rapturous, that I think once you experienced it, once you had undergone this almost holy communion, life could never be the same again. People hugged endlessly; hugged friends, hugged strangers, hugged trees and sometimes tried to hug the police. With the benefit of age and hindsight, it may have been somewhat naïve and chemically artificial almost but by god, it felt good at the time.

Our dancefloors were the ultimate in egalitarian democracy, a communal space where all are equal; where women could dance without inhibitions and without getting groped or propositioned by predatory men. Dancing created a space within which you could succumb to the music’s sensuality and rhythm and just do your thing, no matter how strange it might be considered by mainstream society. I had grown up endlessly going to gigs, usually to spend an hour or so watching some people, nearly always male, play instruments on stage while drinking warm lager from a plastic cup. At many of these gigs people, again mostly male, would mosh at the front, which is a euphemistic word for drunken pushing and fighting and inherently macho.

For us, gigs now just looked archaic and obsolete, the old bands like dinosaurs. Our parties would go on for a minimum of twelve hours, often days. ‘Seventy-two hour party people’, to quote a sympathetic journalist. There were no stars, no hero worship, the DJ’s were usually invisible and dancers faced in all directions. The parties were free, they drew eclectic and energised crowds that would never have mixed socially or geographically before, and beneath the stars we danced together in our church, our temple, a movable temple with no walls and no barriers. Life, it is said, is not a search for happiness but a search for belonging and so deeply did we feel this brave new belonging that three decades later people are still avidly discussing those parties and festivals and this sense of wonder at what we achieved provided the motivation to write this book. It was a compelling story, life-enhancing for the participants but utterly unseen by the media at the time.

Dreaming in Yellow by Harry Harrison is out now via Velocity Press. You can purchase the book direct from VP here.