GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #13

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

Born in East Dulwich, London in 1943, Guy Stevens was crucial to the foundations of UK DJ culture – a black music enthusiast, he played US rhythm & blues, rock & roll, jazz, surf music, Phil Spector productions and Jamaican ska at the pivotal West End mod venue, The Scene - a prime hang-out for adherents of this hugely influential London-originated subculture.

His record collection was the stuff of legend, Stevens often sourcing directly from the US, helping trigger a long-running British obsession with imported American dance music.

Kicking off his Monday R&B sessions at The Scene in 1963, playing tracks on labels like Chess, Stax and the various Motown imprints, his audience would come to include members of The Who, The Small Faces, The Yardbirds, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles.

What Stevens was playing at The Scene would prove to be a big inspiration for Roger Eagle, who, also in ’63, would become DJ at Manchester’s hallowed R&B/soul club, The Twisted Wheel, where the Northern soul movement would later take shape.

As president of the Chuck Berry Appreciation Society, Stevens brought the rock & roll icon to the UK for his first tour in 1964, the same year he began to run the R&B label Sue, licensed by Island Records owner Chris Blackwell. Sue UK, at Stevens’ instigation, would begin to issue tracks not only from the New York parent company, but other American R&B labels – this would eventually lead to the termination of their deal later in the decade.

With swinging London beginning to embrace a new psychedelic direction, The Scene would close in 1966, whilst Stevens would broaden his horizons, becoming head of A&R at Island, whilst writing for Record Mirror.

He was key to the formation of the band Procol Harem. At a party, he’d commented to lyricist Keith Reid that a friend had turned ‘a whiter shade of pale’, prompting one of the defining songs of the era. Unfortunately for Stevens, Chris Blackwell declined to sign the band.

1968 was a testing year, with Stevens jailed for drug offences. Worse still, whilst incarcerated his precious record collection was stolen. On his release he returned to Island and set about working as a producer with rock bands including Free, Heavy Jelly, Mighty Baby, and most notably Mott The Hoople (who he named, having read the Willard Manus book of the same name whilst in prison).

Alcoholism curtailed his career, but he returned for one final hurrah, producing the legendary Clash album, ‘London Calling’ (1979). Stevens died in 1981, having overdosed on prescription drugs he was taking for his chronic alcohol dependency.

Streetwise Records was set up in 1982 by Boston-born record producer Arthur Baker, who’d started out as a soul DJ in the city during the ‘70s. His first taste of the cut-throat music industry came when the legendary remixer Tom Moulton acquired the tapes to a disco album Baker had been producing in Boston’s Intermedia Studios, but rather than re-record the tracks, as Baker had been led to believe, Moulton remixed them instead, releasing as his own ‘T.J.M’ album in 1979 without crediting its true producer.

Undeterred, he placed ‘Kind of Life (Kind of Love)’ with NYC’s West End label for a 1979 release under the North End moniker. Moving to New York in 1981, his breakthrough came via North End’s ‘Happy Days’, issued on Emergency.

Baker came to international attention when he produced and co-wrote Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force’s game-changing ‘Planet Rock’ for Tommy Boy in 1982. The track would usher in the electro era, with Baker central to its early evolution.

Setting up Streetwise that same year, further success came with the colossal ‘Walking On Sunshine’ by Rockers Revenge, an Eddy Grant cover that reached #1 on the US dance chart and #4 on the UK singles chart. Other 1982 highlights included ‘Nairobi & The Awesome Foursome’s ‘Funky Soul Makossa’, covering Manu Dibango’s afro-funk classic, and Baker & Cosmo Wyatt’s remix of British jazz-funk favourite ‘Ease Your Mind’ by Touchdown. He’d also take the leftovers of the ‘Planet Rock’ session to create ‘Play At Your Own Risk’, released on Tommy Boy by Planet Patrol.

In 1983, boy band New Edition topped the US R&B and UK singles chart with ‘Candy Girl’, whilst ‘I.O.U’ by British group Freeez returned Streetwise to the summit of the US club chart (also a UK #2). Baker would then co-write and produce New Order’s ‘Confusion’, released on Manchester’s Factory Records (UK), and on Streetwise (US). - the session also spawning ‘Thieves Like Us’, which appeared on Factory the following year. He’d also produce further Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force singles, ‘Looking For The Perfect Beat’ and ‘Renegades Of Funk’.

With Baker’s remix/production skills increasingly in demand from established artists like Bruce Springsteen, Diana Ross, Hall & Oates and Bob Dylan, the label was wound down in the mid-‘80s. He would subsequently collaborate with the Criminal Element Orchestra, whilst releasing his own Arthur Baker & The Backbeat Disciples album ‘Merge’ (A&M 1989).

Moving to London in the ‘90s, Baker set up a number of bars and restaurants. Continuing to produce into the new millennium, he can still be found on DJ line-ups around the globe.

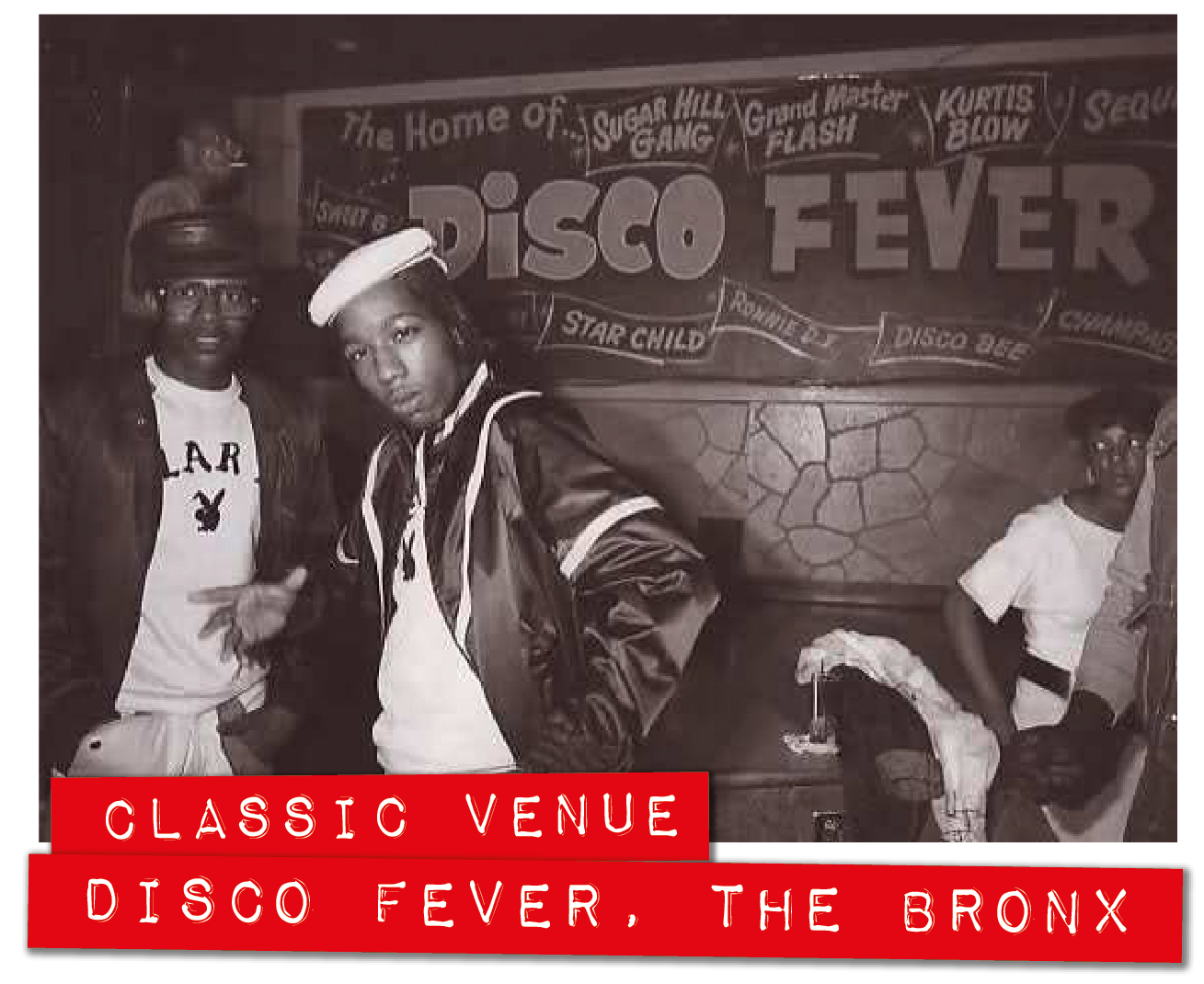

Having emerged undisturbed from the Bronx block parties of the 1970s, hip-hop was ready to explode throughout New York as the decade came to a close. At that crucial moment, Disco Fever became a central hub for the movement.

Originally one of Albert Abbatiello’s many clubs, Disco Fever was something of a failure until the baton was handed to his son, Sal in 1976 – its new identity forming when DJ and bar manager Sweet Gee started hyping up the crowd over the microphone in a rap style.

Sal Abbatiello set about finding some local crews to book, inviting DJ Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, to perform there – this subsequently became a regular slot. By 1978, Disco Fever was open seven nights a week and became a focal point for hip-hop. Rap pioneer DJ Hollywood would be convinced to leave the Bronx’s other notable disco, Club 371, to take on a regular slot at Disco Fever, although many would cite the ill-fated Junebug as the club’s quintessential DJ – he was the subject of the 2010 documentary ‘White Lines And The Fever: The Death of DJ Junebug’.

Abbatiello brought in many more New York acts including, The Cold Crush Brothers, The Treacherous Three, Kurtis Blow, Kool Moe Dee, Disco Four, Crash Crew, Funky 4 + 1, The Sugar Hill Gang, The Sequence, Spoonie Gee, T-Ski Valley and Spyder Dee, plus early appearances from Run-DMC and LL Cool J.

With a community-orientated approach, Abbatiello only hired people who couldn’t get other work. He set up a local basketball league and hosted a number of fundraisers. Disco Fever filled the family void for many and the club was well respected. It was a place where rival gangs could enjoy music side by side – there was even a speakeasy-styled warning system installed in case the police showed whilst people were getting high in the back rooms. Major issues were avoided until 1979 when one of the club’s security staff was shot dead and a metal detector had to be brought in on the door.

Abbatiello launched Fever Records in the early ‘80s, issuing mainly hip-hop and Latin freestyle tracks between ’83-’98 by artists including Sweet G, ‘Love Bug’ Starski, Nayobe, M.C. Chill, The Cover Girls and Lisette Melendez.

The mid-‘80s hip-hop movie ‘Krush Groove’ was something of a double-edged sword, on the one hand helping immortalise Disco Fever, one of its locations, on the other bringing about its demise - the attention surrounding the shoot attracting the scrutiny of the local authorities, who would consequently shut the club down for not having all the proper licenses and permits.

‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ was written by Clifton Davis and originally recorded by The Jackson 5, however it’s the version by legendary disco diva Gloria Gaynor in 1974 that’s best remembered.

The Jackson 5 performed it as a reflective love song, with a 12-year-old Michael Jackson showing incredible maturity on lead vocal. It topped the US R&B chart, stopping just short at #2 pop. Hot on its heels was a second classic rendition, Isaac Hayes taking a more seductive approach in reaching #5 R&B and #22 pop.

Gaynor’s version, released on MGM in late ’74, was a completely different animal – a rousing dance floor anthem produced by Meco Monardo, Tony Bongiovi and Jay Ellis, which was one of the defining tracks of the early disco years.

Starting out as a singer with the Soul Satisfiers, Gaynor had seen scant success during the ‘60s and throughout the first half of the ‘70s, yet, following ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’, she’d be crowned the original Queen of disco (her successor, Donna Summer, 12 months away from her first hit).

Tom Moulton, remix pioneer and inventor of the 12” single (still to be invented at this point), provided a significant innovation by making side one of the album continuous - creating a seamless medley of the tracks ‘Honey Bee’, ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ and the Four Tops cover, ‘Reach Out, I’ll Be There’. It was a revelation, the first DJ mix on vinyl. Whilst side two took an orthodox approach, compiling five tracks that were all around the usual radio-friendly three minutes in length, Side one was ‘a 19 minute disco suite’ that established Moulton firmly at the vanguard of his field. ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ topped the US disco chart, whilst the side one triad weighed in at #2 a few months on, once the album was issued.

A top 10 hit on both sides of the Atlantic, ‘Never Can Say Goodbye, would return to the UK top 10 in 1987, covered by The Communards, whilst 1978’s ‘I Will Survive’ cemented Gaynor’s diva status, becoming a symbol for female emancipation, as well as the New York Times’ choice as the top gay anthem ever.

Gaynor’s popularity waned amidst the anti-disco backlash of the following years. She gradually turned to Christianity, distancing herself from her disco past, but was soon tempted back, recording a further gay anthem, ‘I Am What I Am’, in 1983.

Her career would enjoy a renaissance in the early ‘00s when two of her singles, ‘Just Keep Thinking About You’ and ‘I Never Knew’, topped the US dance chart.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Stevens' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here