GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #18

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

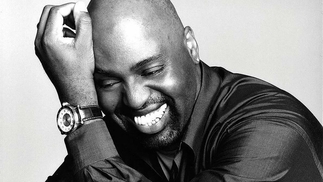

Bronx-born Frankie Knuckles (Francis Nicholls) was an honorary Chicagoan bestowed with the title ‘Godfather Of House’.

Having started out playing soul, funk and disco in the mid-’70s filling in for Larry Levan, his childhood friend, at New York’s gay bathhouse/nightspot, the Continental Baths, in 1977 he moved to Chicago to take up residency at The Warehouse – a position initially offered to Levan, who declined, instead embarking on his own journey to DJ eminence as the guiding force behind NYC’s game-changing Paradise Garage.

By the early ’80s the music Knuckles played at The Warehouse had gained its own category in Chicago’s Imports Etc. record store, racked under the shortened heading ‘house’, unwittingly planting the seeds for the birth of a dance music movement that continues to fill floors worldwide – the irony being that house music was never played at The Warehouse (Knuckles moved to The Power Plant in 1982, whilst The Warehouse, renamed The Music Box, hired DJ Ron Hardy, setting in motion a whole new phase for Chicago, which would serve to ensure Knuckles’ legend).

Whilst house remained largely marginalised in the US, it exploded into mainstream consciousness in the UK, Europe and other parts of the world, where Knuckles’ DJ appearances were in great demand.

Famously describing house as ‘disco’s revenge’ in 1990, he belatedly hit back at those who had declared disco ‘dead’ in 1979, following on from Chicago’s infamous Comiskey Park baseball stadium record burning frenzy whipped up by shock jock Steve Dahl under the banner of ‘Disco Demolition Night’.

Also known for his recordings, production and remixes, his most successful was ‘The Whistle Song’ (1991), a top 20 UK hit. The track he’s best remembered for wasn’t one of his own, but Jamie Principle’s ‘Your Love’. Having championed the original demo, Knuckles took the artist credit when issued on seminal Chicago label Trax, by way of Frankie Knuckles Presents - Principle’s name not appearing at all. ‘Your Love’ would take on a whole new lease of life when a spin-off mash-up that married the track with a Candi Staton acappella called ‘You Got The Love’ went huge in the underground clubs, and, via an official 1991 release by The Source & Candi Staton, would climb all the way into the UK top 5.

Two decades on, the city of Chicago honoured him, naming a section of South Jefferson Street, where The Warehouse once stood, Frankie Knuckles Way - a decision backed by the then Illinois state senator, Barack Obama.

In 2014, 59-year-old Knuckles died in Chicago of diabetes-related complications – his final appearance at London’s Ministry Of Sound just two days earlier.

Founded at the perfect moment to unleash a torrent of Jamaican music, Trojan was an unrivalled force when it came to reggae in the UK.

Formed by Island Records in summer 1967, it initially focussed on the output of producer, Arthur ‘Duke’ Reid. Reid used a Croydon-built Trojan truck to cart his sound system around Jamaica – his music consequentially referred to as the ‘Trojan Sound’.

The label was one of several reggae imprints born of an Island/B&C Records partnership, its first release Reid’s ‘Judge Sympathy’. In summer ’68 Lee Gopthal who had worked with Island boss Chris Blackwell on mail order sales, took the helm. Gopthal instigated a new strategy, licensing the output of producers like Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Leslie Kong and Edward ‘Bunny’ Lee, to complement Duke Reid’s. He positioned Trojan as the parent label, with other reggae labels from the B&C/Island deal becoming subsidiaries.

Ska had been a staple with the Mods since Jamaican-born DJs Count Suckle and Duke Vin introduced the music into London’s nightlife in the early ‘60s. The first Jamaican artist to have a UK hit was Millie Small, who scored a 1964 #2 with ‘My Boy Lollipop’. However, this was in isolation - it wasn’t until 1967 that JA music began to properly infiltrate the mainstream with chart entries from Prince Buster, The Skatalites, Desmond Dekker & The Aces and The Ethiopians, as well as the homegrown Pyramids. Dekker soon became reggae’s best-known artist, his 1969 single, ‘Israelites’, the UK’s first Jamaican #1.

Although there was a wait for the hits, Trojan was an instant cult success, picked up on early by the burgeoning working-class skinhead sub-culture - an offshoot of Mod. The Downtown label provided Trojan’s chart breakthrough courtesy of Tony Tribe, a British-based Jamaican who scraped into the top 50 in summer ’69 with the Neil Diamond song ‘Red Red Wine’.

The floodgates opened in late ’69 when Jimmy Cliff’s ‘Wonderful World, Beautiful People’, reached #4 and ‘Long Shot Kick The Bucket’ by The Pioneers just missed the top 20. A string of hits followed for artists including Cliff, The Pioneers, The Maytals, Nicky Thomas, Horace Faith, Desmond Dekker, Bob & Marcia, Greyhound, John Holt and Ken Boothe. Dave & Ansel Collins gifted Trojan its first #1 (via the Technique label) with 1970’s colossal ‘Double Barrel’, whilst the label itself eventually reached the summit with Ken Boothe’s ‘Everything I Own’ (1974). The eight-volume ‘Tighten Up’ compilation series further enhanced Trojan’s kudos.

The hits dried-up in the mid-‘70s, but Trojan, via re-releases of its formidable back-catalogue remains a touchstone for reggae enthusiasts and a key incubator of bass culture.

Situated in New Jersey’s Newark, the legacy of Club Zanzibar and its ‘Jersey Sound’ are often obscured behind the big New York clubs of the 1980s, however its influence in the formation of house cannot be ignored.

In the mid-‘70s, Miles Berger bought an old Holiday Inn and transformed it into the Lincoln Motel, setting up a small club inside called Abe’s. The DJs in the early phase were Gerald T, who’d previously played in the Holiday Inn bar/nightclub, and Hippie Torrales (probably best-known for the 1988 house classic, Turntable Orchestra’s ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’, which he co-wrote and produced).

Gerald T guided Berger initially, convincing him to get Richard Long to install one of his, now legendary, sound systems and move to the large ballroom upstairs; styling it on that of the Paradise Garage, whilst taking its lighting cues from Studio 54.

Zanzibar opened in September 1979, with Joe Robinson of Sugar Hill Records, also based in New Jersey, bringing a test-pressing of ‘Rapper’s Delight’ for Gerald T to play for the first time in a club.

Party promoter Al Murphy moved the club further towards the Garage, with a more casual dress code, replacing Torrales with Larry Patterson, previously DJ at local gay club, Le Jock, on Fridays, whilst New York Better Days legend Tee Scott took over Saturdays (Gerald T would remain in the second room until 1989). Patterson subsequently brought the likes of David Morales, Larry Levan and François Kevorkian to play the club too.

Zanzibar also hosted live acts, often linking up with the Paradise Garage to bring over UK acts whilst US artists like Loleatta Holloway, Chaka Khan, Sylvester, Roy Ayers, D-Train and Grace Jones performed at the club.

In 1982 Tony Humphries, the son of an expatriate Columbian salsa musician, who had just started working with Shep Pettibone on NYC’s seminal radio station 98.7 Kiss FM, extending tracks for their Mastermix series, talked himself into a Wednesday night slot.

Humphries built a reputation for his remixes, 1982’s ‘The Smurf’ by Tyrone Brunson and ‘Last Night A DJ Saved My Life’ by Indeep and Visual’s 1983 proto-house favourite ‘The Music Got Me’ setting the standard.

As the ‘80s unfurled the soulful side of house resonated at Zanzibar, which was tagged the ‘Jersey Sound’. Humphries made his UK debut at Shoom, London’s hallowed acid-house party, in 1990, and later took up a residency at Ministry of Sound, whilst becoming an Ibiza regular.

As Humphries spread the ‘Jersey Sound’ overseas, Zanzibar moved more and more towards hip-hop, renaming itself Brick City. The venue was eventually demolished in 2007.

‘White Lines (Don’t Don’t Do It)’, with its cocaine theme, was such an unusual record when it first appeared in 1983; way different and leftfield even by electro standards. The overall sound provided a totally new aural experience - it was rap, it was electro, it had funky brass sounds, but it was also laced with a flavour of ‘50s doo-wop.

Having issued 1979’s ‘Superappin' on Enjoy Records (a previous record, ‘We Rap More Mellow’, was credited to The Younger Generation), Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five would rise to prominence on Sugar Hill, releasing their first single, ‘Freedom’ in 1980. The 1981 cut-up masterpiece ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’, introduced turntablism to vinyl, but Flash’s deck skills were absent on 1982’s global hit, the socially-conscious rap classic ‘The Message’, with MCs Melle Mel and Duke Bootee alternating over an infectious downtempo electro groove. However, an ensuing royalties dispute led to Flash filing a lawsuit against the label, with the crew breaking-up as a consequence.

Although Flash had no part in the record, ‘White Lines’ is confusingly credited to Grandmaster & Melle Mel – the Grandmaster name in dispute at the time.

Written by Melle Mel and the force behind Sugar Hill Records, Sylvia Robinson, this was undoubtedly one of the most distinctive releases of the ‘80s, somewhat disturbingly playful with regards to its subject matter – the track punctuated with double-meanings via cocaine-user slang like freeze, rock and, instead of bass, freebase.

Although big on the UK’s electro underground, ‘White Lines’ would be a slow grower with the general club populace, many DJs finding it initially hard to get their heads around this unique record. This is highlighted by its extraordinary UK chart history. Released here in November ’83, it spent just 3 weeks in the lower regions, peaking at #60 (purely as the result of specialist support), before eventually returning two months later, when it climbed all the way to #7, amassing an incredible 38 consecutive weeks on the chart. Its chart life would span late ‘83 and the bulk of ‘84, before making its final appearance in January ’85. Whilst an instantly recognisable UK classic, it never fared as well back home, failing to place on the US chart, although it went top 10 dance.

The record proved to be somewhat ill-fated. The backing track was a re-recording of Liquid Liquid’s ‘Cavern’, who weren’t credited as writers, prompting a legal battle that resulted in the demise of both Sugar Hill and the influential No Wave label, 99, for whom Liquid Liquid recorded.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Knuckles' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here