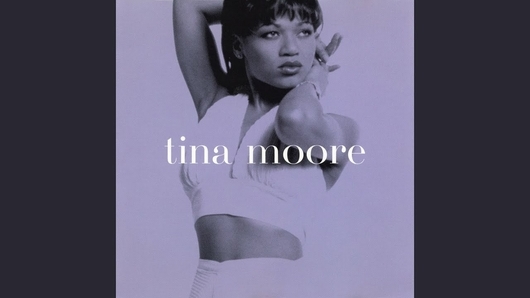

How Kelly G’s remix of Tina Moore’s ‘Never Gonna Let You Go’ laid the blueprint for 2-step garage

When Kelly Griffin was tasked with crafting a remix of American R&B singer Tina Moore, he decided to try something a bit different — and in the process, he laid the groundwork for the 2-step garage sound that swept London and then much of the rest of the UK in the late 1990s. DJ Mag’s Ben Cardew tracks down Kelly G in the US to hear the story of a true game changer

The complex, multi-inspirational ways in which music evolves means it is generally impossible to say what record was the starting point for a particular musical genre. And yet for 2-step, the gambolling offshoot of UK garage that rose to dominate the UK charts in the early 2000s, you could make a strong case for Kelly G’s Bump-N-Go Mix of Tina Moore’s 1995 single ‘Never Gonna Let You Go’ as being the spark that put the 2 in 2-step.

The song had the syncopated synth lines, the bass pressure, the sparkling vocal line, and the touches of R&B, house, US garage and hip-hop that would later crystallise into the 2-step sound. More importantly, it had the two-step bass drum rhythm that would characterise 2-step as distinct from UK garage. It was insanely catchy, too, with hooks piled alongside hooks and was everywhere in the UK in 1997, as 2-step started to emerge. “What was the first 2-step record? That Tina Moore record was the first US one,” Timmi Magic, of UK garage pioneers the Dreem Teem, told Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton in 2005 for the Red Bull Music Academy. “It was the first 2-step track that really got people going.”

The story behind Kelly G’s Bump-N-Go Mix and 2-step is a charming tale of inadvertent musical connections. But it is also an unlikely story, in many ways. 2-step was largely a British musical movement but Tina Moore is American, as is Kelly G himself. Almost three decades on, G — aka Kelly Griffin, a genial music executive from Chicago, now in his early 50s — says he wasn’t really aware of what 2-step and UK garage were, even as his remix was becoming a mainstay on garage compilations.

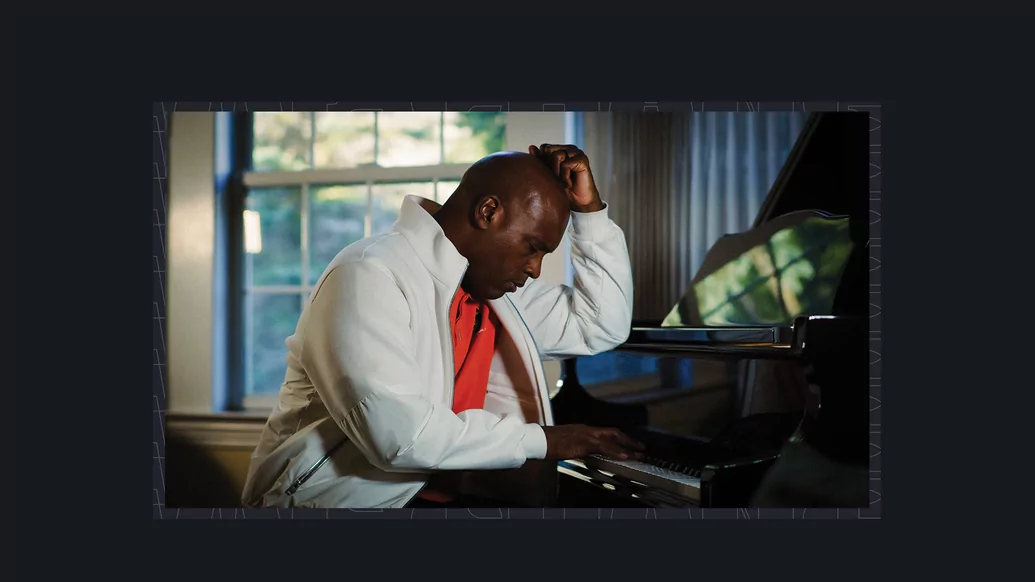

“I had no idea, to be honest with you,” he explains on a Zoom call from New York, where he works as head of content strategy for record label 300 Entertainment. “Jere McAllister [a Chicago house DJ, producer and keyboard player] called me and we were just talking. He said, ‘You know that mix you did is doing really well?’ I was like, ‘Really?’ This is pre-internet, pre-cellphones. So calling the UK was like, ‘I ain't calling over there! It’s gonna cost me a gazillion dollars’.”

“I had no idea, to be honest with you, Jere McAllister [a Chicago house DJ, producer and keyboard player] called me and we were just talking. He said, ‘You know that mix you did is doing really well?’ I was like, ‘Really?’ This is pre-internet, pre-cellphones. So calling the UK was like, ‘I ain't calling over there! It’s gonna cost me a gazillion dollars’.” — Kelly G, aka Kelly Griffin

Another popular misunderstanding about Kelly G’s Bump-N-Go Mix was that it was released in 1997, just as 2-step was starting to emerge from the London underground. In fact, the mix was re-released in 1997; but it originally came out in 1995, when UK garage wasn’t much more than the niche music of a popular pub afterparty. Kelly G’s Bump-N-Go Mix was one of nine versions of the song on a double 12-inch, alongside mixes from Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley, Torin Edmond, Steve ‘Miggedy’ Maestro and Jere McAllister.

By this point, Griffin was working for Hurley, after impressing him with his mixes for Chicago radio station WGCI. “I studied Industrial Engineering and Management Science at Northwestern University,” Griffin explains. “On that campus, I DJed everywhere.” When Griffin left Northwestern he got a job developing Windows software at Kraft Foods; there he met someone in the mailroom who knew the programme director of “the number one station in Chicago”: WGCI. Two years later he left Kraft to take a full-time job at the station.

“I was working with [Chicago radio DJ] Steve Harvey on the morning show, and then Saturday nights I had a mix show that played house, hip-hop, R&B and everything,” Griffin explains. “And Steve Hurley had heard me on there and heard all the different radio remixes I was doing and asked me to join his team. Obviously we’re fans of Steve Hurley, Steve Hurley’s a god!”

It was as part of Hurley’s crew that the opportunity to remix Tina Moore, an R&B singer from Wisconsin, emerged. This was a big opportunity for Griffin; but it was also a puzzle: how on earth do you compete with a Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley house remix? The solution, for Griffin, was to try something different. “The biggest influence [on my remix] was, I can't compete with Steve Hurley, I need to do something different that would complement the entire package,” he explains.

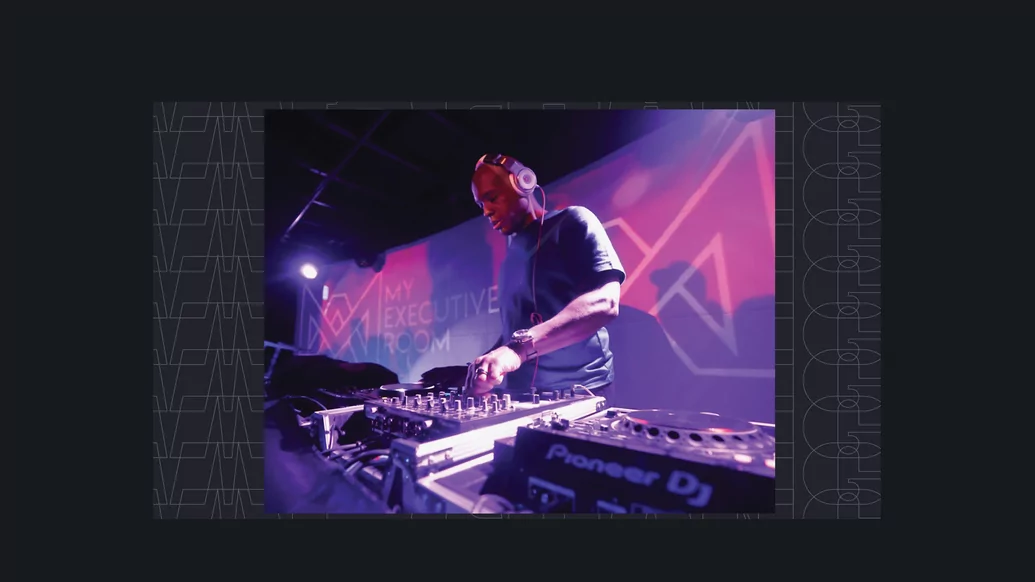

The most obvious difference in Griffin’s remix (which was split into two parts for release, the Bump-N-Go Mix and the Bump-N-Go dub) was the bass drum, which had a two-hit rhythm — the ‘bump’ in the remix’s title — rather than the standard four-to-the-floor of house music. Griffin also added his own backing vocal hook — the song’s iconic “ka-boom chickaboom never”. “It was a vocal processor I had, I used to use it for the radio stuff that I was doing,” Griffin explains. “I grew up on funk, house, but the funk part was Roger Troutman, Zapp, George Clinton, that vocoder, I was always a fan of that.”

That wasn’t the remix’s only hook, of course. Griffin also manipulated Moore’s vocal into a seminal wail that would later be sampled by Double 99 in another UK garage anthem, ‘RIP Groove’. “That's always been my thing,” Griffin says. “In my remixes I find some sort of phrase to repeat because in my head when I'm dancing, I want that. Something consistent that I walk off the dancefloor and I keep repeating in my head.”

It is difficult to say why, exactly, Griffin’s remix appealed so much to UK audiences. But we suspect that the song’s combination of Korg M1 synth — the same keyboard that was famously used by Stonebridge on his remix of Robin S’ ‘Show Me Love’ — and its slight air of grime appealed to a British audience who were coming to UK garage from the harsh, soulful sound of jungle. “My bread and butter was always hip-hop because I was on a radio station. So I played a lot of hip-hop. But I love house,” Griffin says. “Even my mixes today have that grime of hip-hop.”

Because Griffin’s mix was so different, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s crew weren’t entirely convinced, at first. “I’ll never forget when we had that session and we all sat down to play our mixes and mine was going [sings song] ‘Doom doom — per kak! — doom doom’. And everybody’s like, ‘Okay...’” Griffin says, his voice trailing off in palpable disappointment. They didn’t like it? “No, they all looked at me like crazy!” Griffin laughs.

“I can’t make a track for you and hope that you like it. To me, that’s not the method. The records that often blow up, that do really, really well, are records that were in the creator's mind a fluke. Or were just, ‘Hey...’.” — Kelly G

In the end, though, his remix passed. “They were like, ‘Okay, well, we'll submit it and see what happens’,” Griffin explains. “And the rest was history all of a sudden.” Well, not that sudden. It took about a year for word of the song’s success in the UK to filter back to Griffin and — as is often the way — it is not quite clear how the song first caught on. Producer Noodles told Joe Muggs in his book Bass, Mids, Tops that Unity, the London record shop where he worked, took 10 copies of the ‘Never Gonna Let You Go’ double 12-inch on Christmas Eve 1995. “We played it in the shop and everyone went mad,” he said. “That was the real beginning of the [2-step] vibe for most of us.” Other people swear London station Kiss FM was first to get behind the tune, while the support of DJs like The Dreem Teem and Tuff Jam was surely important.

Momentum behind the song grew rapidly, and in August 1997 UK label Delirious re-released ‘Never Gonna Let You Go’, with Kelly G’s BumpN-Go mix taking pole position, the release charting at No.7 in the UK. By this point, remix offers had started to flood in. “There was a bunch of people lined up at my door, wanting a Tina Moore-like remix,” Griffin says. “And I said, ‘Okay, but Tina Moore was Tina Moore, right? I can’t capture that magic in a bottle for your song’.”

More than anything, though, Griffin took advantage of his success to DJ internationally. Hurley, he says, took him under his wing, with the two collaborating on a 12-inch called ‘Go Down Moses' featuring Sharon Pass in 1998. “I would see Steve Hurley go out there [on tour] and young fans would ask him for his autograph and a photo with him. And in Chicago, he was just regular Steve Hurley. So that always fascinated me,” Griffin says. At the same time, Griffin maintained a parallel career in the music business. He stayed with WGCI until 1999, when he moved to BET. These days he works for 300 Entertainment, which was bought by Warner Music in 2021.

His US colleagues, Griffin says, have little idea that he produced one of the most iconic remixes of the last three decades. But the British are a different matter. “When I talk to some of our UK colleagues and somehow we come up with music, I’ll tell them, ‘I did this record with Tina Moore’. And they go [shocked and rather posh-sounding British accent]: ‘Oh my gosh! That was your record?!’

“I don't feel like I was ever able to bask in the success of it per se,” he adds. “Yes, I got work out of it. But it was just one of those things that was part of my repertoire that blew up. When I met Estelle,” he laughs, “Her being from the UK, when she found out, she was like [another British accent], ’Oh my god, you did that record!’ That to me never never gets old.”

Maybe, though, things are changing for dance music in the US, with Beyoncé and Drake both releasing house records in 2022. Does he think house music could be making a commercial comeback in its country of birth? He smiles. “I’ve got an inkling. And even the CEO of 300, who's from Baltimore, Kevin Liles, is getting that inkling as well,” he says. “I believe the pandemic will give birth to some more encouraging, uplifting, spiritual music. And it will come in the form of house music.”

Griffin will be well placed to make the most of the opportunity, should house music enjoy a mainstream moment. 300 is currently working on a project “documenting and preserving the house music culture from Chicago”, while Griffin continues to DJ and make music, with remix projects coming on Defected and Chicago producer Terry Hunter’s label Mirror Ball Records. He is also working on a record called ‘Power Of One’ with legendary soul singer Candi Staton, which he says will be “a monster”.

Come what may, Griffin’s place in dance music folklore is assured. More importantly, his remix of Tina Moore is proof of the good that can come from the two-way cultural flow between the US and UK, which has been helping music to evolve since The Beatles. (See also: Rosie Gaines’ ‘Closer Than Close’, another US record that blew up in the UK’s garage scene.) For Griffin, meanwhile, the lesson from his pioneering record’s strange success is “make music for you”. “Because at the end of the day, people feel something that's authentic,” he concludes. “I can’t make a track for you and hope that you like it. To me, that’s not the method. The records that often blow up, that do really, really well, are records that were in the creator's mind a fluke. Or were just, ‘Hey...’.”