How Soul II Soul’s ‘Fairplay’ carved a new path for Black British soundsystem culture

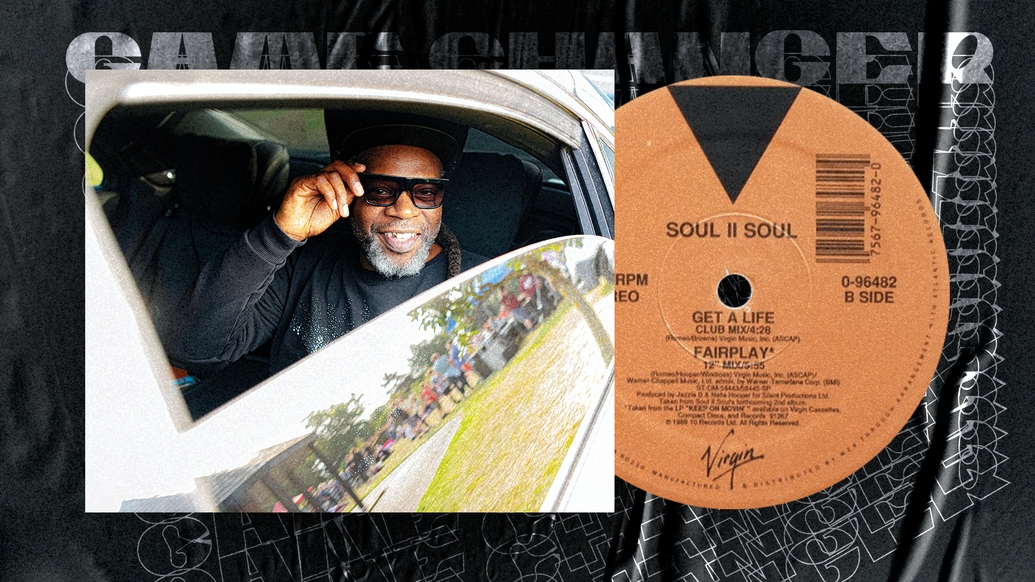

Soul II Soul helped give Black British music and UK club sounds a truly unique identity. Collective founder Jazzie B talks about their ground-breaking debut, ‘Fairplay’, and traces his journey from London soundsystem culture to global star with Ben Osborne

When, after a series of near misses, Jazzie B and DJ Mag finally connect, Jazzie’s in a taxi heading for a video shoot.

“I’m not good with calendars,” he laughs about our missed connections. But in reality, he’s just relentlessly busy. Amid DJ sets, live gigs, radio shows and book launches, his 1990 Grammy-winning track with Soul II Soul, ‘Back To Life’, has just been nominated for another Grammy, this time for a remix by Booker T. He has a schedule worthy of any up-and-coming pop star, which is pretty impressive, given the track we’re here to talk about, 1989's 'Fairplay', is over 30 years old.

The second youngest of a family of 10, Jazzie (aka Trevor Beresford Romeo OBE) was born into soundsystems. “I was tiny,” he recalls of early experiences,“and fascinated by the whole thing; the sights and smells of the valve amps. I built a transistor radio and remember hearing ‘Bennie And The Jets’ for the first time on it, and going to Alexandra Palace and hearing DJ Emperor Rosko.

“But my first proper involvement was the Queen’s Jubilee [1977]. It was just outside my door — it was a massive street party, and I got paid for it as well,” he flashes a trademark grin. “I told everybody I got paid six quid — but actually got £12! That’s where the vision began. From there, it became Jah Rico (Soul II Soul’s original name), after I hooked up with Daddae (Phillip Harvey) in school.”

Having formed a soundsystem, he began using his family’s community networks, giving Jah Rico a national platform.

“All my things, when I started, were in the community — the gigs were in community centres, and the church was a big influence. The congregation moved around, so when they had trips, they used to have a party at the end of the trips. And the trips would take us anywhere from Bristol to Chapeltown in Leeds.”

The excursions effectively gave him a tour network with a readymade audience. In some places, such as Bristol, the audiences contained actual family members. But there were community connections in all.

“These people were like our family. We’d come down from Leeds and go to Manchester, Leicester, Sheffield, Nottingham, coming all the way back down. In all those places, all working-class, we had all the different communities — all within our church.”

While the upheavals of the late ’70s — including power cuts and the winter of discontent — were ravaging Britain, Jazzie was learning his craft by partying.

“It was all fun,” he recalls. “Cutting our teeth against the backdrop of a three-day week and Thatcher coming in — and all that disruption. It was brilliant. Happy days. Maybe the most influential propeller was the punk era. That attitude changed the basic landscape of London at the time. That gave us opportunity.

“We were moving out of the class system,” he continues. “A bit like America — a bit of a free-for-all. Thatcher had given carte blanche to entrepreneurs — and there were lots of geezers back then knocking things out. You know what I mean? It gave us opportunities to weave through the nooks and crannies...”

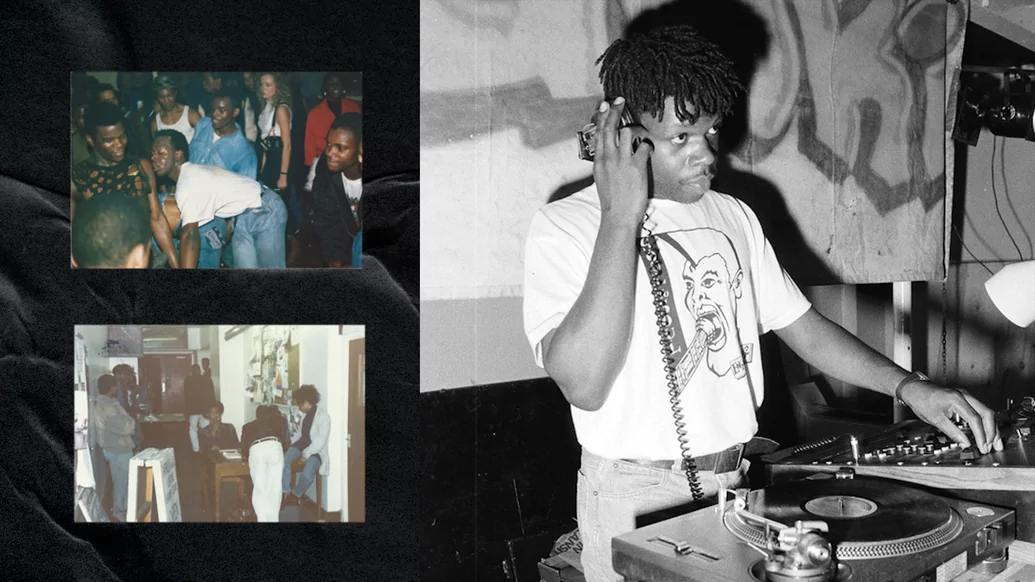

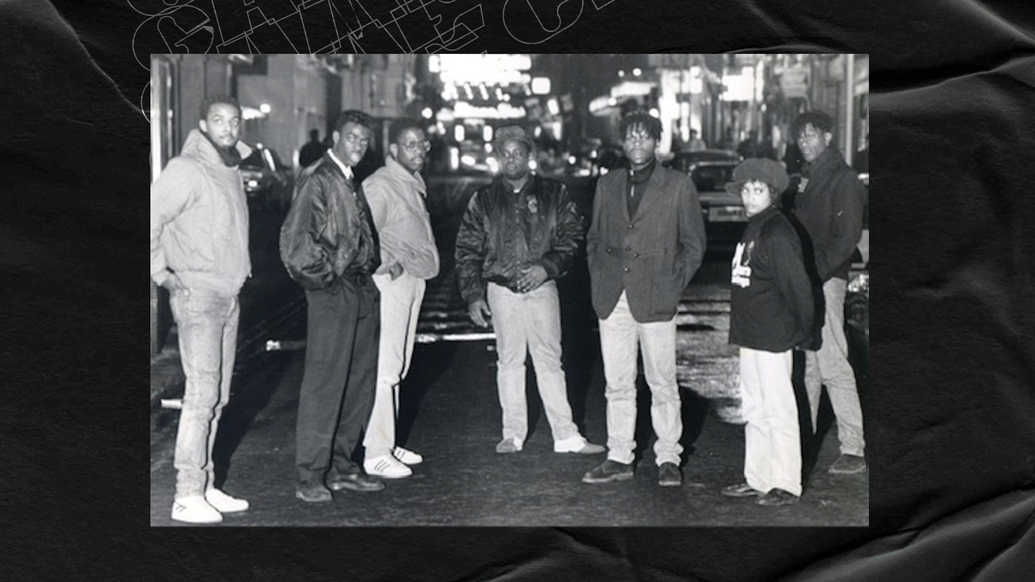

Jazzie and Daddae took the opportunity to go beyond soundsystem boundaries and develop a new eclectic approach. “We had technically started out as a reggae soundsystem,” he recalls. “But we made the choice to make it about the dancers. What we represented was a soundsystem that was inclusive rather than exclusive. Facing our audience really changed everything. And we were into electro and hip-hop, alongside all the other great music that was coming out of the ’70s.”

Bringing new genres into their sets, and mixing in wider styles, began to make Jazzie and Daddae stand out. “Soul music didn’t really have an influential presence outside of what we were doing,” says Jazzie.

Another important adaptation was making the soundsystem full-time. “A lot of the soundsystems in the 1970s were part-time — a hobby. But we decided to take it on as a full-time venture, having had the different experiences and contacts that we had.”

Combining such elements as rare groove, breakbeat and house, they changed their name to Soul II Soul to reflect their eclectic approach. “We included electro and the soul music of the time — and because of sampling, we were playing all those rare records, from James [Brown] all the way through to whoever, and breaking songs and stuff like that,” Jazzie says. “The mixture of the music started to become a unique selling point — and the fact we had a ‘sonical’ soundsystem that sounded really good, meant that we could really illuminate even the really shitty pressed records. So we took the philosophy of a reggae soundsystem and built a new form of music and attitude — which you couldn’t really label.”

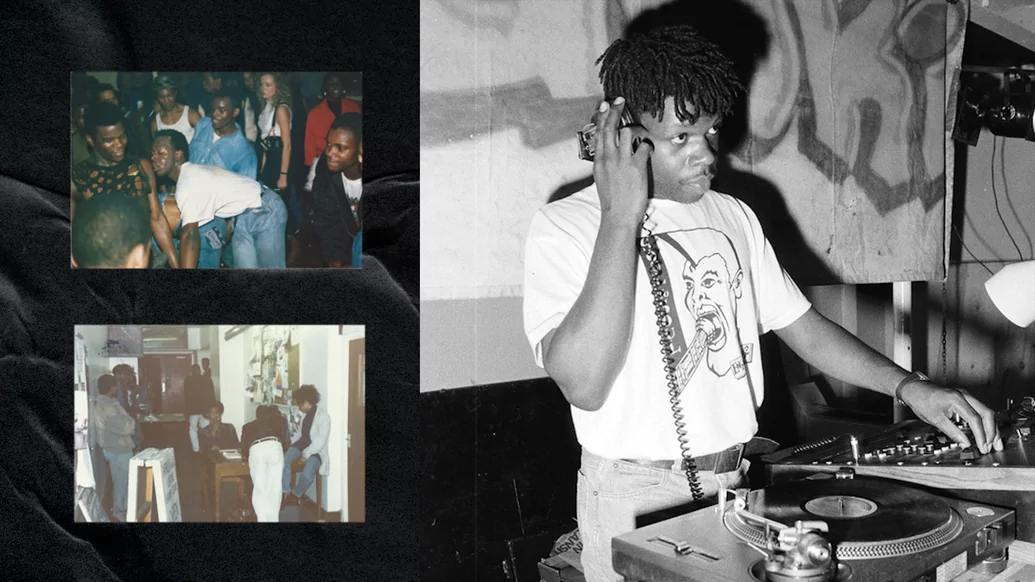

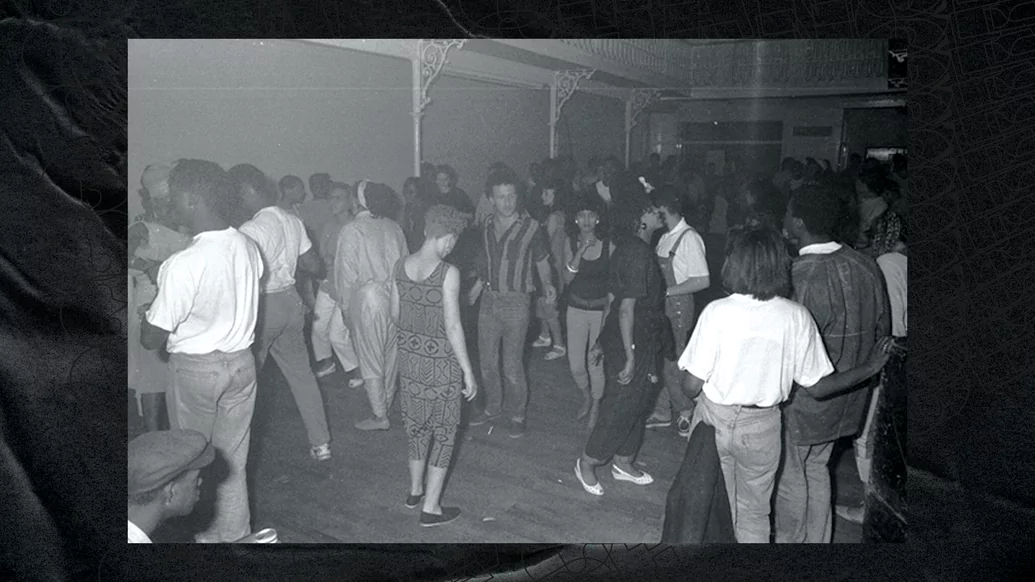

Meanwhile, they stayed focused on their crowd. “It allowed it to build,” says Jazzie of the increasingly eclectic audience. “We were in North London playing at community centres. We were current in Camden and Hackney, and places like that. So you can look at that and see you’ve got an undercurrent going on. But it really happened when we started doing the universities. It started pulling in people that were also really into art.

“A lot of disco music was being played and it was anything that was a bit more interesting than the norm,” he continues. “You could expect to hear Sylvester through to Darryl Pandy. A lot of Chicago stuff, a lot of Trax and Fingers Inc... that was the mould. It was leftfield and unique. And the type of people that were coming was a cross-section. A lot of that could only have taken place in London.

“We had technically started out as a reggae soundsystem, but we made the choice to make it about the dancers. What we represented was a soundsystem that was inclusive rather than exclusive"

This eclecticism informed Jazzie’s DJing. “My style wouldn’t traditionally be in a soundsystem. There are other eclectic DJs out there, but my uniqueness was always the sonics, which gives you a way of playing — with attitude.”

In other ways, Soul II Soul stayed immersed in soundsystem culture, including the practice of pressing dubplates. “Technically, the soundsystem is something you build yourself from scratch. So the whole thing is a DIY culture. And traditionally, you make your own dubplates or ‘specials’.”

The ‘specials’ made soundsystems stand out, and were jealously guarded. But, as with so many things, Soul II Soul flipped this tradition on its head. “Basically we wanted to be the biggest soundsystem in the world. And we figured the way to do that would be to have every other soundsystem playing our records. So I did something that you wouldn’t do in the soundsystem world. I released one of our dubplates, which was ‘Fairplay’. And that makes the rest history. When you listened to the groove of ‘Fairplay’, originally, in the warehouse parties and blues and those jams with the Wild Bunch [Nellee Hooper’s Bristol outfit], that would have been part of our exclusive repertoire.

“We’d be cutting up beats and vocals over it,” Jazzie adds. “We used to play Martin Luther King’s speech over it. Then Rose Windross would voice over the top. If you listen to the lyrics, she’s explaining what happens on a Sunday night [at the Africa Centre]. But if you take the composition, the anorak music people will tell you it’s not even a structured song. It’s just a groove.”

Central to ‘Fairplay’s genesis was the decision to start a night in central London.

“Africa Centre came about because we got fed up with the warehouse scene and how drug and gangified it had got,” Jazzie says. “So we flipped the script. The venue was chosen specifically because of the sprung dancefloor, the balcony gallery and the fact it was in Covent Garden. But the flex was that it was on a Sunday. We figured the hoodlums and that lot would be recuperating on Sunday. It filtered out all the shitty people and gave room to the people who were into what we were doing.

“It was those people that made it famous. It wasn’t a big venue, it didn’t last very long, but I’m never going to say it was a myth; because the dream continues,” he grins. “We had a very weird door policy — we sort of reversed everything. And you can see the rub, because people like [future collaborator] Simon Law came out of that. Simon would have got in because he looked weird — we were all about that.

As the music morphed into place at the Africa Centre, Jazzie made use of his day job as a studio sound engineer.

“We started to record in Addis Ababa studio, in Harrow Road,” he recalls. “But we worked in lots of different studios, like Lilly Yard — then the album was recorded at Britannia Row, Pink Floyd’s place. People involved included Nellee, Simon Law, Rose Windross, Caron (Wheeler), Doreen Waddle — so many different people.”

The equipment they used included old analogue gear and new technology that was just becoming affordable. “We used SSL G series, loads of experimental things, and it was in the days of tape. You can draw a line back to when the Falklands War happened. That made the technology available. I fell into the category where the electronics became affordable. Because we were all geeks, technology played a massive role in our evolution, and the development of our sound. I guess that’s why, when you listen to those songs today, they still sound pretty fresh.”

Having recorded the tracks, they needed a label. But again, their approach challenged the rules of rock ’n’ roll.

“Whereas guitar bands were cutting demos and waiting for record companies, we were making the music and playing it to a readymade audience. So we were doing pretty good on our own circuit, and picking up traction on the underground across the world.

“I’d got a residency in New York and was playing across most of Europe. That’s how the whole thing developed. We had our audience to dictate where our sound was going and where we formed our ideas. Outside of that, the public got involved once we’d signed a deal with Ten Records.”

With their tracks already recorded and an existing audience, they could more or less choose their label — and signing to Virgin subsidiary Ten was a no-brainer. “It was just a matter of who we chose, and we chose Virgin. As a kid I’d bought a collection of records on Virgin called ‘The Front Line Collection’. In those days, the record companies often dictated what was going on — but we are such an unusual set-up that they didn’t know what to expect... in fact it was probably best they didn’t understand. But when it hit, it just blew up.”

Despite the label not “understanding”, ‘Fairplay’ took off under its own momentum in the UK, and America soon followed.

“The thing about America is, it’s really regional,” says Jazzie. “So New York, LA, San Francisco, are more international territories. But you don’t get into cornflake country until you plug into their system — and it’s not until you get into the Midwest that you start picking up traction.

“And that’s what happened. It was timing. The music was different. The airwaves in the US were saturated with new jack swing. So it was Soul II Soul coming along with a different sound, and the industry trying to find something new. Great timing. The funniest thing is, England didn’t really get it. Journalists in England thought we were American. So we never really got recognised in the UK (at that stage). It was great for us circulating Black America, being Black and British. And in those days, it was very segregated... we went through all the wars.”

Famously, while the British music industry failed to recognise Soul II Soul with an award, in the US, they won two Grammys in 1990, for ‘Back To Life’ and ‘African Dance’. But Jazzie is far from holding any grudges. “It’s perfect for me, because it means I’ve got more longevity. It goes all the way around the atmosphere to come back here — and by the time it’s back here, we’re on the next spin. It’s been great really.”