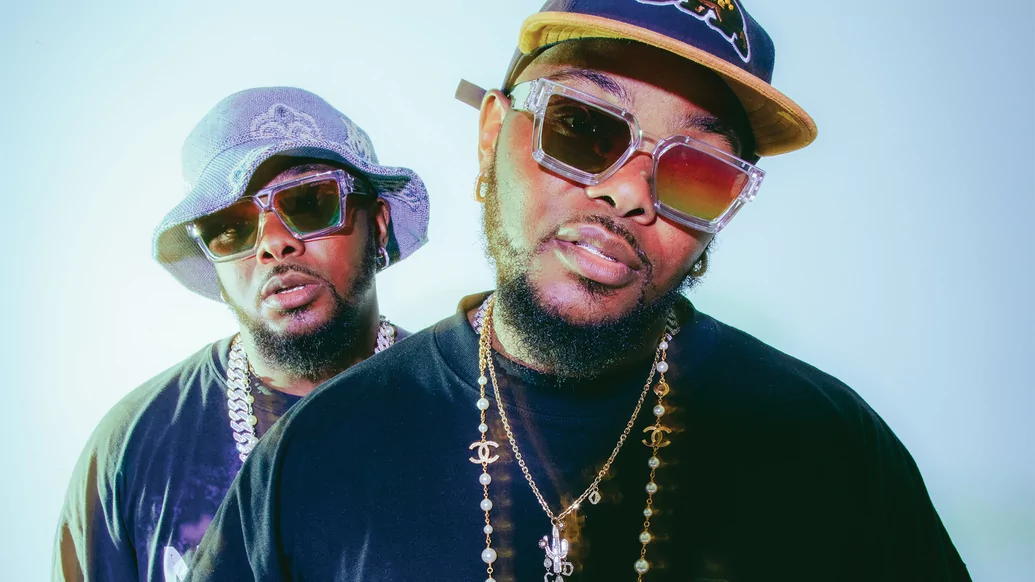

Major League Djz: amapiano’s global ambassadors

Major League Djz are taking the sound of amapiano into spaces that others cannot reach. The South African twins may not have been the first to start pioneering the genre, but they have picked up the mantle and run with it. DJ Mag’s Ria Hylton meets them at their temporary base in West London to talk about their history and effectively becoming amapiano’s global ambassadors

No one does house like South Africa, and in South Africa amapiano reigns supreme. To be sure, you’re unlikely to find SA deep house heads at an amapiano night, but there’s no denying the emotional connection that a sound barely into its teens has brought to the dancefloor, birthing cultural transition not seen since kwaito. Further afield, the genre has spawned collabs with Afrobeats superstars on the continent’s west coast and hip-hop heavyweights in the US, connecting SA to fellow Africans and Africa to the diaspora in new and spiritual ways.

And no one is pushing the sound more than Major League Djz. Best described as amapiano’s global ambassadors, Banele and Bandile Mbere have managed to convey the material conditions of the culture — how things look and feel, as well as sound — to new audiences around the world. During the pandemic, their Balcony Mix series brought renewed attention to the sound, and ever since they’ve been touring the globe, inspiring others with their cross-genre collabs. Having sold out London’s Brixton Academy in 2021 and rocked Coachella last year — the first amapiano act to do so — the brothers returned to Europe this summer with a sold-out residency at London’s HERE at Outernet, three nights at Ibiza’s Circoloco and festival slots across Europe, including Afronation, Tomorrowland and Kappa Futur. A genre born in the townships has gone global, and now all eyes are on Major League Djz.

Except, when DJ Mag arrives at their air bnb in Putney, South West London, the twins are nowhere to be found. Co-collaborator LuudaDeeJay opens the door, makes a quick call and relays that they’re 20 minutes away, so we nestle into a plush cream sofa and wait. Their assistant calls not too long after with an update. By the time we get our final ETA, DJ Mag is sitting in the duo’s temporary studio for an exclusive listen in on their tech-driven tracks, and when they finally arrive, we learn that they were in fact at the barber’s. The detached five-bedroom house we step into is not dissimilar to the apartments shown in their Balcony Mix series, a spacious dwelling with high-ceilings and smooth marble-like surfaces. Banele wanders into the kitchen to greet us, motions to a glass table and sits. We follow suit. Bandile slips in not long after, takes the chair opposite and smiles.

Two weeks earlier the duo played a sweltering set at DJ Mag’s HQ, taking a packed Thursday early evening crowd through a mix filled with classic R&B vocals, house remixes and, towards the end of the live stream, the ‘Wetsalang’ dance challenge. The video, one of our best-performing streams, hit over a quarter of a million views as we went to press. “The response on the dancefloor was amazing,” Bandile replies when we ask how the HQ went for them. “The energy in sets like that, I like them because everyone’s so concentrated and they really want to feel the sound. Playing exclusive music helps you understand what people want. They give you a reaction and you can understand what you need to add to a song, if you can release the song, things like that. It’s always a nice environment to play exclusive music in that setting.”

“Kwaito showed what the youth was going through... ’Hood kids on the street, rapping to house music, that’s what kwaito was. That’s why it got so big, rapping about politics, fun, girls and guys, about how you’re living — your state of mind at that moment just after apartheid.” — Bandile

Amapiano’s deep house origins, intricate percussion patterns, jazzy keys and soulful vocals evoke all sorts of emotions on the dancefloor. Deep and expansive, it summons a playful energy, calling on skankface and whistle-like expressions among its faithful dancers. When early pioneers like MDU aka TRP slowed down their productions and introduced the log drum, giving tracks that warm melodic bassline, a new SA house sub-genre was born. “The log drum, oh my god,” Bandile moans, leaning back in his seat. “MDU aka TRP actually came with the log drum.”

Since the early ’10s the sound has been constantly on the move. From sgija (pronounced skee-ga), a percussion-heavy sub-genre, and Pretoria’s bacardi, best known for its hard drums, piercing hi-hats and whistles, to private school, closely associated with Kabza De Small, Josiah De Disciple and the kwaito sound most associated with acts like Ama Roto and Too Short, this sound is far from slowing down. Banele mentions the quantum sound coming out of Pretoria, a sub-genre with a darker, sustained bassline, as something to watch. When played loud, it gives off the impression of a slightly distorted speaker playing close to the ear. “This thing will mess up your speakers,” he grins, playing us a track.

Major League Djz are, in many ways, hip-hop to the core, but that braggadocious energy behind the decks looks different up close. Most of our time together is spent discussing the effort they make trying to bring parts of the industry on board. “There’s a lot of convincing and cultivating to do,” Bandile shares. “With amapiano, a lot of it is still in the Afrobeats space, so a lot of Afrobeats promoters are booking amapiano DJs and they don’t understand dance shows,” Banele adds. “The sound, the positioning of the DJ booth, they don’t get it yet. I prefer DJing at dance shows because people just want to dance.”

But they’re playing superclubs and getting billed alongside superstar underground talent, like recent DJ Mag North America cover star Chris Lake, we reply. “Right, but I don’t think any other amapiano DJs can play in those spaces,” Banele counters. “We’re speaking to a lot of different spaces and we’re not playing the same stuff that we’re playing at Outernet to a SA crowd, to a diasporic crowd to what we play in Ibiza. It’s still about building confidence, for the promoter and for the consumers.”

With Ibiza more specifically, it’s been a tricky time. They debuted on the White Isle last season and are slowly making inroads, but it’s still, if they’re honest, a bit of a slog. “I think we are accommodating the crowd more,” Bandile adds. “We are adding more tech sounds in our sets and making a type of sound that connects more, we call it pianotech. Before we weren’t adding it as much, but now it’s really connecting. And you can see the numbers going up.” His eyes sparkle. What was the DC-10 dancefloor like last week, we ask? “Ah, we built it up nicely. There were maybe eight people [at the start] and it ended with like 400.” He even mentions the new fans recruited at the barber shop an hour earlier, simply by playing mixes for the whole shop to hear. “I was just watching everyone, nodding their heads, just observing and thinking, ‘Yeah, this thing is quite special’.”

“One of the most notable things about Major League is their vision, their foresight and business acumen — they’ve really pushed things forward and been serious about building a brand,” amapiano DJ Charisse C tells DJ Mag over the phone. As someone who’s been pushing amapiano through her No Signal radio shows, guest mixes on NTS, BBC Radio 1 and BBC Radio 1Xtra, and collaborations with SA-based artists, Charisse is well-placed to speak on their rise. “I see them as vessels, they’re significant conduits,” she continues. “Their storytelling, their documentation of culture and them being DJs, doing DJ Mag, selling out Brixton Academy, playing Ibiza — that’s very much the trajectory of an electronic dance music DJ. They’ve broken that door.”

Among all the significant milestones however, courting different crowds, the duo explain, remains very much a trust-building exercise. A slow conversion. As is convincing promoters and underground DJs that their sound can work in different places. “Some dance DJs get it and they’re like, ‘Yeah, this is the next big thing’,” Bandile explains, “but a lot of people are still not there yet, so it’s a lot of convincing to do to get into the space you actually want to be.” And so, as big as they are, Major League Djz have always been careful to meet new audiences halfway. Whether it’s playing classic house vocals over exclusives, arranging amapiano remixes of well-loved songs, or incorporating techier sounds in their productions, they’re keen to do whatever it takes to connect them with new listeners.

If that wasn’t struggle enough, they also face resistance at home, with many in the scene wary of the global spotlight they’ve brought to the sound. “I think they’re still trying to protect it too much and not allowing it to grow. I think they’re scared to let it go, because maybe they won’t have control of it anymore,” Banele explains. “We like to keep things to ourselves; even with kwaito, it never transcended.” Fears of the sound being watered down, cut and pasted and/or being overrun by fairweather producers are understandable, but what Major League Djz fear most is not being able to bring the genre into new territory.

It’s an observation Charisse C also notes. “I think for a lot of South African artists, it’s very easy to become comfortable with being the king of your ’hood, making music for your ’hood and not thinking about how things can go beyond that. They’ve really raised the bar for what’s possible.” There’s another delicate balance they strike — nurturing new talent so the genre continues to evolve, while honouring its roots and the communities that have taken it this far. In its early days, amapanio travelled mainly by word of mouth, in WhatsApp groups and through mixes uploaded by producers wanting to showcase their latest batch of work, rarely making it out of certain locales. “It needs to grow bigger than that,” Bandile explains. “We don’t do radio edits — we need to formalise things more so the sound can get into those different spaces.”

“I think for a lot of South African artists, it’s very easy to become comfortable with being the king of your ’hood, making music for your ’hood and not thinking about how things can go beyond that. They’ve really raised the bar for what’s possible.” — Charisse C

The reality is, Major League Djz feel the pressure to push amapiano for the whole community worldwide. This sound has crossover potential and if anyone’s going to break it, it’s them. But they can’t go it alone, which is why they’re keen to bring as much talent along with them. “When you’re in the position of the person who has to break a sound, you have to figure out how to meet audiences where they’re at too, while still holding on to your integrity,” Charisse explains. “Because they’ve kicked down a lot of the doors, I imagine they’ve been in that place, having to contend with that conflict. I don’t know if this is true for them, I’ve never asked them, but I don’t know if there’s a pressure that comes with being in that position.”

Banele and Bandile were born into political royalty. Their father, Aggrey Mbere, was forced into exile by the white-ruling apartheid regime in the ’60s for his work in liberation movement the African National Congress (ANC), then classed as a terrorist organisation but now the governing party in South Africa. After a few years in the US, he settled in Boston, got his PhD in education at Harvard, and continued to agitate for the anti-apartheid cause. Aggrey met their mother, Musa, at his best friend and South African jazz legend Hugh Masekela’s wedding, and in 1991 the twins were born. Word has it Aggrey invited Nelson Mandela to Boston after he was released from prison, and on the leader’s election in 1994, the family returned home. Aggrey was made South Africa’s ambassador to Rwanda in 2001, but died two years later, just as the twins were about to enter their teens.

At age 15 the twins threw their first party in Johannesburg North, a suburb of the country’s most populous city, making their first real mark in the industry. The roads surrounding the event that night were gridlocked, filled with cars borrowed from the parents of underaged teens, as well as peers who failed to get in. “That party was crazy,” Bandile remembers. “It changed our lives.” It made their names too. Up-and-coming artists began reaching out for their support on album launches and soon they were organising concert after-parties for the likes of Fat Joe, Rihanna, 50 Cent and Jay-Z. But when did they start DJing? “When the DJs didn’t show up,” replies Bandile. “When they started coming late, like we were for you today,” Banele teases, deadpan.

We’re happy to report that Major League Djz are bang on time for their London gig the following evening. The queue into HERE at Outernet still weaves round the corner as midnight, the time of their set, approaches. The guys have sold out all four Saturdays at the superclub, attracting heads from the amapiano, Afro-house and Afrobeats scenes, and when they take over from DJEFF the main floor is heaving. They rustle up tracks like Uncle Waffles’ ‘Tanzania’, Mellow & Sleazy’s ‘Chipi ke Chipi’ and the current hit ‘Mnike’, while skankfaced dancers dip and flick their hips as the night deepens. Bandile brings a certain swagger to the front of the decks halfway through, amping up the crowd before leading us in a dance reminiscent of Soca’s ‘Follow The Leader’.

We meet UK amapiano promoter Rose Bere on the mezzanine level and get chatting — what does she make of the night so far? “They’re playing all the hits,” she grins, before dipping back into the dance with her crew of ravers. Bere, who’s been promoting club nights for over a decade and got turned onto amapiano a few years before the pandemic, has a simple explanation for why the brothers have blown up in the amapiano space so quickly. “It’s definitely their selections and the energy that they give when they’re on stage,” she explains over the phone a few days later. “They’re trying to get into these new spaces, so they’re playing what people know. For now they’re playing for those that don’t listen too much to [ama]piano.”

As someone who’s put on nights in Ibiza herself, as well as Piano Love events in the UK, the promoter’s intimately aware of the labours ahead for Major League Djz, and the gruelling task of translating a sound for different audiences. “I love DJs that give us the exclusives, give us new tracks and take it back as well. They were taking it back [on Saturday], giving us some 2019, 2020. It’s just about building that trust with the audience.” The constant evolution of the sound is promising, which bodes well for the scene as a whole, she says, referencing gqom as a contrast. “We’re definitely having this discussion about how gqom came out and then disappeared. It was being moved to the side because other sounds were coming out as well. I do appreciate that people like Charisse C will still go to the club and play it, but obviously it didn’t evolve like amapiano has. They are making it broader, so they’ve been able to touch different spaces — I definitely think they’re on the right path.”

Benele and Bandile got behind the decks aged 17. Hip-hop DJ Dr Peppa showed them the ropes and soon they were warming up their own events, as well as filling gaps in line-ups when booked acts failed to show. They spun tracks by The Fugees, Lauryn Hill, LL Cool J and other classic rap acts, and slowly grew their name. But it was only in the mid-’10s when DJs tired of playing US hip-hop started releasing homegrown music, that SA hip-hop began to blow up, and the twins spotted their moment — an opportunity to craft a deeply SA sound that would work beyond its borders, building on what kwaito had achieved a generation before. “Kwaito showed what the youth was going through,” Bandile explains. “’Hood kids on the street, rapping to house music, that’s what kwaito was. That’s why it got so big, rapping about politics, fun, girls and guys, about how you’re living — your state of mind at that moment just after apartheid.”

Amapiano is directly linked to kwaito, he adds. “You see this dancing trend in amapiano? It started in kwaito and the guy who started it was King Arthur,” he offers as an example. “Every song he came out with had a dance — he was the king of kwaito.” Raised on the sounds of TKZee, Arthur Mafokate, and Trompies, the brothers were intimately aware of the cultural and political impact of the sound on their generation and laid down plans to restore a genre they felt still had much life left in it. “In South Africa, they painted kwaito as a dead genre,” continues Bandile. “With Ricky Rick, Casper and Okmalumkoolkat we tried to rebrand it as the authentic sound of our country, just with a hip-hop twist. We called it new age kwaito and we mixed the English vernacular with our home languages, to make it more cosmopolitan.”

“At that time we weren’t saying amapiano — I was clueless about amapiano, but we just wanted to try out different sounds. We were making amapiano without realising.” — Bandile

They threw down chuggy productions, pushed a hip-hop aesthetic through their music videos, and brought on top-tier rap talent to front the whole thing. This new sound they coined ‘new age kwaito’ would have an international appeal and put them on a bigger map as cultural ambassadors. Their first release, ‘The Bizness’, landed in 2014, followed by ‘Slyza Tsotsi’ and ‘Zulu Girls’ in 2015. Around the same time they were promoting South African artists through their Major League Gardens day festivals, a key moment in the Jo’Burg events calendar. Afrobeats stars like Davido were billed alongside long-term collaborators Rick and Nyovest, as well as house DJs Shimza, Euphonik, Black Motion, and of course Black Coffee. But their dreams of reviving a much-loved house genre, as well as their renown in SA for putting on parties wasn’t big enough. So they dreamed bigger.

Amapiano was in good health in the late ’10s, when Major League Djz started to listen to the homegrown sound more closely. “Amapiano is kwaito,” Bandile proclaims halfway through the interview. “There was a song we did, ‘Sgetit’ with Cassper and Kwesta. If you listen to it, it’s kwaito but it’s also amapiano. At that time we weren’t saying amapiano — I was clueless about amapiano, but we just wanted to try out different sounds. We were making amapiano without realising.” Artists like KWiish SA, whose ‘Iskhathi’ track probably broke the sound for a whole new group of people, were early on their radar, but Scorpion Kings’ debut album was a big game changer for the scene. A collaborative project between producers Kabza De Small and DJ Maphorisa, the record took amapiano into new territory, mainstreaming the sound and inspiring a new generation of artists. Over a decade on from hosting their first party, the twins had finally found a calling worthy of their ambition — they would spread the gospel of amapiano.

By the time the pandemic hit, the brothers had already switched their sonic palette and already released the amapiano-leaning ‘Ase Trap’ EP. As far as they were concerned, they were firmly in the amapiano space — the only problem was, it wasn’t clear whether fans were aware of the pivot. “We wanted to switch from kwaito to amapiano,” Bandile explains. “We were thinking: how do we get people used to us playing another sound? So we said we’d do mixes, but then decided to put visuals to them, so we could show people the culture, what is really happening with the sound.” They launched the Balcony Mix series on YouTube, which got its name from the balcony apartments they performed on, and streamed sets every Friday throughout lockdown. An audience of millions looked on as the Djz spun unreleased tracks from sunny rooftops across Jo’Burg, often with other amapiano acts in tow.

The sound was known outside of SA, but at that point had no chosen champions. Major League Djz put a face to it all, presenting a visual culture to connect to a wider audience. And in a remarkably short space of time they turned the world onto a sound. In July 2020 they dropped 31-track album ‘Pianochella’ and later ‘Le Plane E’Landile’ (which takes its name from street slang describing how Covid came to South Africa). It was their first true amapiano track to hit the big time, so big that we even hear reverberations of it in the crowd at Outernet, the way an audience at a UKG gig might chant “Oggy oggy oggy”.

When the world started to open up again, Major League Djz wasted no time getting international gigs. They hit the States and were among the first SA amapiano artists to secure gigs in Europe. Soon they were getting billings in Ibiza, and even collaborated with Nando’s on an EP with up-and-coming artists. By late 2021 they were playing Balcony Mixes in far-flung locations like Diplo’s Malibu estate, and had landed a record deal with Atlantic Records. They dropped the ‘Outside’ album that same year too, and sold out Brixton Academy, to the surprise of many close to the scene. It was another breakthrough moment in the genre’s ascent.

But with all that under their belt, the overwhelming feeling is that there’s still much to do. With all eyes on Major League Djz and a genre not wanting for quality productions, Banele is sure that amapiano has a healthy future — but only “if you take care of it,” he caveats. “We gotta let it grow and go into different spaces.” So what does success look like? He shares a list, almost as if from memory, of aims including a song in the top 10 of the Billboard charts, Ibiza residencies like Black Coffee, headline shows at stadium-sized venues and bookings at all the major festivals. “Once we have that, then I’ll feel like we’re in a good space.”

It’s approaching late afternoon when we manage to squeeze in a few family-related questions. The story of their father is pretty well-known, but what about their mother? What did she do? Banele has already left the scene, signalling perhaps that our time is up, but Bandile is still at the kitchen table. He looks us dead in the eyes and smiles. “She went to school in America, she met my father there.” It turns out their mother works in the Department of Social Development, as chief director in early childhood development, and has done so for over two decades.

Major League Djz are, at heart, re-interpreting a sound for all manner of listeners in the hope that they can bring as many artists as possible into new arenas. It might take a while, but they’ve never been more sure about amapiano’s crossover potential or their role as messengers. We’re reminded of something said early on in our conversation, by Banele. “I don’t think amapiano has a market yet, not one that is full of us in it. It shouldn’t be just one DJ, it should be four, five of us.” Bandile sums up their task not long after. “Black Coffee said, ‘Don’t focus on home too much, focus on growing the sound abroad’. That’s our mission.”

With thanks to LuuDaDeejay, Charisse C, Rose Bere and DaMs.