Moonchild Sanelly's limitless universe

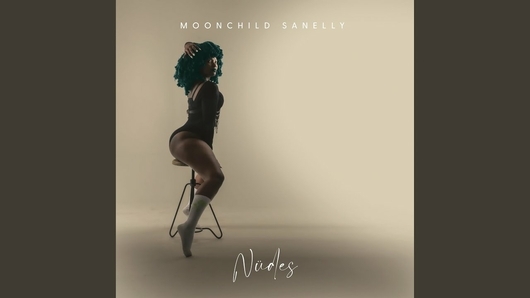

Delivering explosive, quick-witted lyricism over beats that blend kwaito, amapiano and gqom with grime, punk and pop, South Africa's Moonchild Sanelly has become a global sensation. Here, she speaks to Makua Adimora about freedom of expression and her new album, 'Phases'

“I always describe myself as ‘Snow White turns 21 and then the seven dwarfs become her strippers’,” Moonchild Sanelly says matter-of-factly, when speaking to DJ Mag from her home in South Africa. It’s the first of many cheeky one-liners she candidly drops during our half-hour-long conversation. Only days before she flies to Europe for a short tour, she’s casually dressed in a simple grey tee — a decidedly off-duty look for an artist you’re far more likely to catch in a latex leotard and thigh-high gogo boots.

We’ve been speaking extensively about her sonic influences and lessons she’s picked up from pop greats Beyoncé and Tina Turner — crowd control being the most critical. “Seeing her just exuding that power and making people do what you want them to do — that means you can literally affect the world in whatever way you want to,” the singer/rapper says of Turner’s exuberant stage presence.

Much like the Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Moonchild Sanelly exudes an aura of fierce assertiveness, a trait she maintains both on and off the stage. “So, it’s how you use that power,” Sanelly continues, with a shrug. She’s quite the character: speaking a mile-a-minute and offering impish smirks and hearty laughs to accentuate her sharp-tongued commentary. We point at her signature azure blue mop of braids and she immediately tells us she’s named it the “moon mop”. “People think they’re making a joke and say, ‘Oh, a mop?’” she snarks, eyes rolled. “I’m like, it’s so crazy that your eyes are dumber than your brain, because your brain can see the creativity, but your eyes think it’s a joke. I can’t help you there.”

Born Sanelisiwe Twisha, Sanelly grew up in the coastal city of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, amongst an intensely musical family. With a jazz singer for a mother, a hip-hop producer brother and kwaito dancers for cousins, she was automatically exposed to a vast palette of sounds that have influenced her artistry today. From a young age, her mother ensured she was allowed to explore her creative side as freely as possible, whether that was signing her up for dance competitions or buying her materials to encourage her passion for fashion. “I was allowed to express myself, because I was expressive and I was put in the spaces where I could express myself,” Sanelly recalls. “When I was chopping [up] things, I was bought fabric to start making things, instead of being in trouble for chopping [up] sheets. [I was] being recognised for the different talents that I had.”

Naturally, Sanelly developed a keen interest in fashion and went on to study it at the Linea Fashion Design Academy in Durban, but she just couldn’t shake her love for music. After her classes, she’d often make a beeline to the nearest open-mic space. “I don’t necessarily remember a specific moment of saying ‘I’m doing this for life’. I just remember looking for it, to do it,” she admits. It wasn’t long before she had fully immersed herself in the local Durban scene — where the now world-conquering dance music genre, gqom, was born — earning her stripes by writing for reggae bands and freestyling against other rappers.

Sanelly’s eccentric rap style immediately set her apart from the rest. A commanding yet cutesy facetiousness and distinctive drawl have become her trademark; playful, schoolyard-style taunts with emphasis on rolled r’s and nasal accentuations that pay homage to her Xhosa background. Her lyrics were notably elementary, but her delivery packed a punch: on ‘Jiva Juluka’, she passionately incites a mosh from a noticeably passive crowd, while ‘Boys and Girls’ finds her offering coy rhymes about her sexual fluidity.

"I just don’t care what you think, because I am happy with being myself and you’ll adjust [to me] because I’m not gonna adjust to you, however uncomfortable it makes you — and generally, it does make one uncomfortable.”

Such puckish confidence is often reflected in Sanelly’s music, a hyper-vivid blend of kwaito, hip-hop and jazz that she has described as “future ghetto punk”. Over airy amapiano synths and punishing gqom basslines, the 34-year-old approaches music with a brash buoyancy, offering biting critique on various ‘controversial’ topics, from sex positivity to relationships and fake preachers. Proudly labelled as South African dance music’s enfant terrible, she credits her mother as the source of her unapologetically brazen streak. Raised by a single mother with a defiant vein of her own, Sanelly saw first-hand the importance of freedom of self-expression — something she was never denied as a child.

“[Growing up] with that kind of mentality, it’s like your norm,” Sanelly says of her upbringing. “And then when you come into the world, every time they ask you, ‘Oh my God, where do you find the courage?’ I’m like, the courage to be myself? It’s not courageous to be myself. I just don’t care what you think, because I am happy with being myself and you’ll adjust [to me] because I’m not gonna adjust to you, however uncomfortable it makes you — and generally, it does make one uncomfortable.”

Sanelly has since established her place on the music scene, gaining notoriety as one of the most expansive and experimental voices in SA dance music. Collaborating with house legends like DJ Maphorisa, and gqom pioneers DJ Lag and Rudeboyz, she became a superstar on home turf, while simultaneously widening her international reach. And although she faced resistance in the South African industry due to her self-assured nature and controversial lyrics, her unshakeable determination for success guided her down a path of fulfilled manifestation.

Citing Gorillaz, Diplo and Beyoncé as major artistic influences, she has since gone on to collaborate with all three within the span of three years, most notably starring on ‘My Power’, from Beyoncé’s soundtrack album for the live action remake of The Lion King. “You’ll never hear me sound like Beyoncé, but there are a lot of things that I take from [her],” she explains. “First of all, relevance — the power of reinvention over and over and over and over again. The humility that comes with being able to celebrate someone new, even if you can literally hear yourself [in them] — just being able to celebrate them because you know you’re queen.”

Right from the jump, much of Moonchild Sanelly’s discography has exuded a global appeal, while staying true to her African roots. In 2015, she released her debut album, ‘Rabulapha!’, a hazy blend of electronic dance music genres. Adeptly weaving hip-hop, punk rock, house and dance-pop together, Sanelly fused these foreign influences with South African elements like gqom and kwaito to make for a deliciously authentic sound. “We are a currency on our own. Our originality is a currency; our story is a currency,” Sanelly stresses about the importance of paying homage to the motherland. “I’m an ambassador at this point.”

Despite this authenticity, at various points of our conversation, Sanelly also talks about taking a strategic approach with everything in her music — even things as little as incorporating Xhosa into her songs is often a targeted decision. “My accent is even thicker [abroad]; it’s more distinct because I know that it is currency,” she says with a cheeky laugh. “The accent that you laugh at here is the most celebrated and what’s paid for [out] there. So it’s just a matter of just understanding that you’re [innately] rich.”

“My latest phase is that I catch feelings and I cash feelings, because I’m not going to get hurt and waste it when I’ve got a whole diary and I need a beat."

It’s this same approach that laid the foundation for her forthcoming sophomore album, ‘Phases’, which was inspired by her toxic relationship with her ex-fiancé. Sanelly confesses she actually promised herself she’d only leave the relationship once the album was finished. “It’s crazy, I sent that voice note to Lauren [her manager]. I said, ‘Lauren, I know I’m in a fucked-up situation right now, but I don’t wanna cut the relationship because I don’t wanna write from reflection. I want to experience it and write, as I’ve been writing the album, I’m almost done and I don’t want now to make the storyline shaky. And this whole time I’ve been in a relationship. So let’s just finish the album, then I’ll finish the relationship and we’ll deal with the [aftermath] later.’ So I guess it’s just called, what? Immersing yourself in your art?”

As planned, when the record was done, she swiftly became single and free. Vulnerability is a term that isn’t typically associated with Moonchild Sanelly’s more buoyant sound. But on ‘Phases’, she deals with heartbreak in her own way: across the project’s 19 tracks, Sanelly is equal parts hurt and ready to hoe away. It almost sounds like she showed up to the recording session with the intention to express her raw feelings, but she just can’t shake that urge to party.

“It was that moment of, ‘You don’t know me, I’m gonna get over you for real real’,” she chuckles wildly when we put it to her. “I’m not gonna break up with you and then take you back because I’ll be crying over you. I’m gonna get over you while I’m with you. So that when I’m over you, I will not need no tissue because I’m just done, done. So I think I was already celebrating the fact that I already put it down, because I basically wrote down my exit plan.”

As such, themes of sexual positivity, female empowerment and freedom are pulsing through the project’s 64-minute runtime. ‘Strip Club’, featuring Ghetts, flips the male-led narrative, instead putting the woman in charge; ‘Over You’ finds strength and power in breaking up with a cheating ex; ‘Cute’, featuring Trillary Banks, is a straight-up empowerment anthem. Still the project finds moments where Sanelly breaks down those defensive walls. On ‘Favourite Regret’, she somberly reminisces about the good times of the relationship, while on pensive album closer, ‘Bird So Bad’, she pens her desire to escape from it all.

Wielding personal experiences as inspiration for content certainly comes with its downsides — not for Sanelly, though. As the rapper tells us, no topic — or person — is off limits. “My latest phase is that I catch feelings and I cash feelings, because I’m not going to get hurt and waste it when I’ve got a whole diary and I need a beat. It’s a product for me, those experiences for me are a product. So anyone in my life is a song, they just need to make an impact.”

While weaving between a host of genres — amapiano, pop, grime, house, R&B — ‘Phases’ noticeably pays homage to Sanelly’s gqom roots. An ever-evolving sound, South African dance music often sheds its skin over the years and morphs into a new iteration. Sanelly’s rise coincided with the popularisation of gqom — a gritty sound characterised by fragmented basslines and eerie synths — and she emerged as one of the most prominent faces in the genre. But when the markedly slower and more melodic sounds of Johannesburg’s amapiano rapidly took over South African airwaves, Sanelly found herself at the forefront of that, too. “I’m ready for the next one, I’ll have a hit in it,” she says of SA dance’s ephemeral nature. “I feel like in my space, I am literally in my own lane. So if I tap into any lane, I will never be behind. If there’s another genre that comes, I’ll have a hit in it too. Because guess what? I’m a storyteller, I’m not limited to whatever.”

For someone who’s been at the top of her game for over a decade, Sanelly still has the ambition of a wide-eyed rookie — perhaps, another lesson on relevance she’s picked up from Queen Bey. She lets us in on a secret film she’s been executively producing, a documentary about the legalisation of sex work in Southern Africa. Sanelly’s dedication to sexual liberation is her chosen legacy: “I’ll have a statue as a sex icon before they even talk about my music, before they even talk about anything else I do. I’ll be in the books for liberation, with regards to sexuality — and legally.”

But she doesn’t plan to stop there; her end goal is to be an inspiration to Black people globally. “Instead of telling the Black child to go and rewrite their dreams [to fit] what they could do, I literally am living proof. So I don’t have to tell you stories, you can study me, because I live it. I am that Black child, that does things.”