Police are taking down more UK drill and rap videos than ever — for artists, what is the cost?

The Metropolitan Police is removing more rap videos from YouTube than ever before, with recent statistics showing a 1360% increase over the last three years, meaning thousands of aspiring artists have potentially been impacted. But little has been done to ascertain how effective the practice is at reducing serious youth violence. Here, Will Pritchard investigates what impact the takedowns are having on artists in the UK drill and rap scene

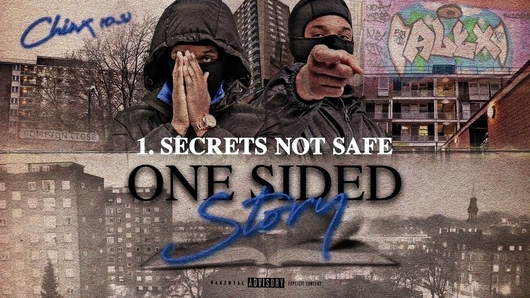

In November last year, North London rapper Chinx (OS) found himself at the centre of an unlikely storm. “It was a bit surreal,” he says. “I was in the gym and my manager’s called me and said BBC Four want to do an interview. They want to speak to you about ‘Secret’s Not Safe’ getting reinstated. I had no clue what was going on.”

For months, the academics, legal professionals, journalists, and former politicians that make up Meta’s Oversight Board — the group tasked with ruling on the social media giant’s most contentious content moderation decisions — had been debating whether Instagram should have complied with a Met Police request to remove clips of Chinx’ blistering debut single, ‘Secret’s Not Safe’.

Now, Chinx was finding out about it in between reps. The Board’s ruling that “not every piece of content that law enforcement would prefer to have taken down should be taken down”, and that the Met Police’s “intensive focus” on drill music “raises serious concerns of potential over-policing of certain communities”, was clear and potent.

For Chinx, it was bittersweet. “At least it’s been noticed,” he says, “but it was still out of my power.” And besides, the slow churn of bureaucracy was months behind the pacy day-to-day of the drill scene — a sound born and raised at the lightspeed of the internet. His breakout moment had passed.

What the ruling had provided, though, was a touch of sunlight on an otherwise opaque policing process. Chinx is just one of potentially thousands of aspiring artists impacted by the Met’s policy of having rap videos removed from YouTube and other social media platforms. His story offers a rare glimpse into the impact that these video takedowns can have on individuals.

Historically, the force has only agreed to partial disclosures when information is requested about the practice — simply sharing the number of referrals made to YouTube, and how many video takedowns resulted. Figuring out which tracks, channels, or individual artists have been targeted has been a case of educated guesswork.

“I just have to find ways to work around it. It’s not fair, but I can’t blame anyone. It’s something I’ve just gotta swallow.” — Chinx (OS)

Last year, according to data released following a Freedom of Information request, the Met’s Project Alpha unit made 1,825 requests to remove rap videos from YouTube, resulting in 1,636 being taken down. The previous year, the London-based force referred 510 music videos to be removed, with YouTube complying in 97% of cases. In 2020, the figure was just 125 — indicating a 1360% increase in referrals over three years.

To date, no other genre has been targeted in the same way. The figures illustrate a significant acceleration in a practice that otherwise receives little public scrutiny or, apparently, much reflection from the Met on its effectiveness as a tactic to reduce serious youth violence.

Despite running since 2019, backed by millions in funding from the Home Office, there has been no public consultation exercise on the surveillance work that Project Alpha officers undertake. A Data Protection Impact Assessment released following a separate Freedom of Information request simply says a consultation “has not been possible.”

When approached for comment on this, a Met spokesperson said: “The officers leading on Project Alpha have plans for community engagement and feedback opportunities in the near future, to continue the conversation around how this violent crime reduction tool is used.”

In 2022, it was revealed that the Met had greatly exaggerated its claims that any consultation had been undertaken before the launch of Project Alpha. Artists affected by Alpha’s tactics are more clear on the impact felt: takedowns disrupt campaigns, costing them money, and cutting their careers off at the ankles.

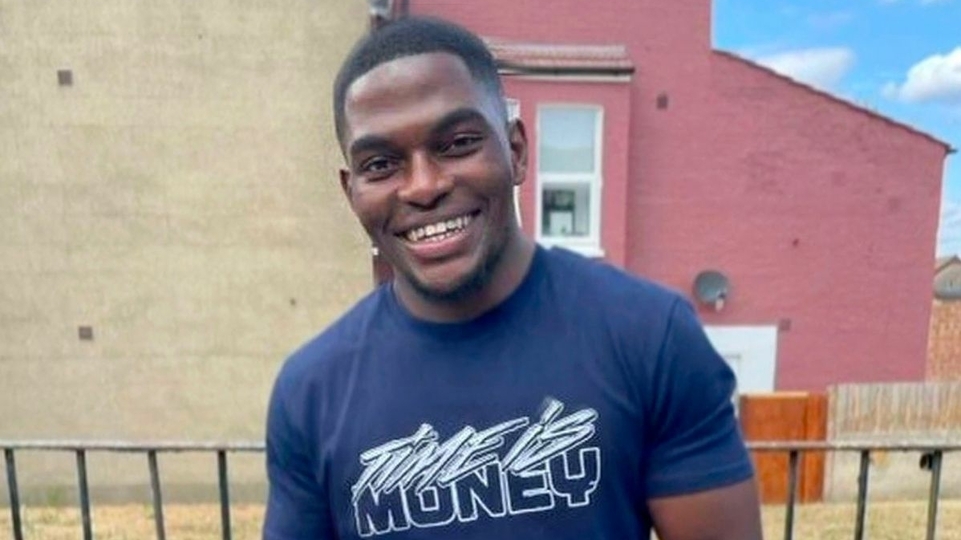

In the baking summer of 2020, as the country dipped in and out of COVID-19 lockdowns, Tottenham rapper Abra Cadabra was on the cusp of a step up in his career. ‘On Deck’, his latest single, had been adopted as a rumbling street soundtrack — its gut-punch bassline and ghostly vocals thickened the air in London’s parks, leaked out of idling cars, and boasted a chorus that had spawned catchphrases and Instagram captions.

“They said they’d taken [Abra Cadabra's] track down because it was slagging off other rappers. I was thinking, ‘How much control do the police actually have when it comes to this kind of stuff?’ Well, a lot, it turns out. I felt very naive to think that that wasn't the case.” — Laura Moat

It was skidding up the charts too, thanks in large part to streams racked up on YouTube. Laura Moat, who was leading digital efforts at the distributor Abra was with at the time, recalls video views of ‘On Deck’ accounting for nearly double the number of chart-qualifying streams than usual.

Midweek, the team went to bed with the track tipping over into the Top 30. ‘On Deck’ was on course for Abra’s highest chart position to date, and set to break a new milestone for the wider drill scene: landing a hit without having to smooth off any rough edges for the mainstream. But by the next day the video was gone, with nothing but an error message from YouTube in its place.

Moat made some calls, ringing around contacts at the streaming site while fielding panicked messages from Abra’s manager. “They said they’d taken the track down because it was slagging off other rappers,” Moat says. Eventually she discovered that the takedown request originated with the Met. “I was thinking, ‘How much control do the police actually have when it comes to this kind of stuff?’ Well, a lot, it turns out. I felt very naive to think that that wasn't the case.”

The label team tried to appeal the decision, but to no avail. “It was just, ‘Computer says no,’” says Moat. YouTube’s policy at the time of having to wait 30 days between appeals meant that the chart campaign stalled, then bumped to a halt. “I think it completely fucked it,” says Moat. “I think we missed the one opportunity to break him into the mainstream. He was pretty devastated.” It would be another two years before Abra Cadabra managed to crack the Top 30, when a Headie One and Bandokay collab, ‘Can’t Be Us’, edged in at number 27.

One of the officers central to the Met’s monitoring of drill rappers at the time was a man named Michael Railton. He left the force in 2022 for a job at Ofcom, and to establish his own private consultancy offering training to expert witnesses called to give evidence about slang and rap music in court.

It’s not known whether he was involved in the decision to refer ‘On Deck’ to YouTube, but while working within Project Alpha Railton helped shape the unit’s approach to having music videos removed, as well as attempting to influence streaming services and radio stations to take similar actions. He describes the aim of the video takedowns tactic as “to turn down the temperature”, and bristles at the way his work has been covered by the press. “We weren’t doing it for stats,” he says.

Railton is insistent that the aim was always to curb spikes in youth violence, and acknowledges the complexities associated with the issue. He says that when drill music includes direct references to people, places, or violent events it is being “maliciously manipulated” to “trigger trauma and trigger shame”. He says that he’s able to draw a clear distinction between expressions that follow the conventions of the genre and those centred on provocation (some would argue that provocation is, itself, a convention of the genre).

“I still boil it down to: hate is hate, bullying is bullying,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if you rap it, sing it, put it on a poster, put it on a billboard, post it on social media. Hate is hate. That’s the issue.” When asked for examples of rappers who’ve been able to use their talents for good, Railton declines to “give anyone a soundbite of ‘endorsed by me,’” before mentioning two grime MCs, Chip and Bugzy Malone. He disagrees that there’s a risk of Project Alpha officers allowing their own personal tastes to influence their decisions.

Railton does admit there weren’t clear methods to measure how effective the takedowns tactic has been in reducing real-world violence — or to consider any unintended negative consequences it was having. Yet he doesn’t think this has been a failing of the approach. “I don’t think it’s a failing at all,” he says. “When it’s coming from a place of public protection, of youth protection, and a reduction of youth violence, a failure is failure to try. If you don’t try, you are failing.”

He appears more hung up on the perception that Alpha’s work has garnered. “The only negative I saw is that it was labelled in a way that we were trying to demonise aspiring artists,” says Railton. “That was never my intention, and that is something that sits heavy for me. I genuinely cared, and I still genuinely care about all those kids I’ve interacted with, and with those I haven’t but whose art I’ve enjoyed.

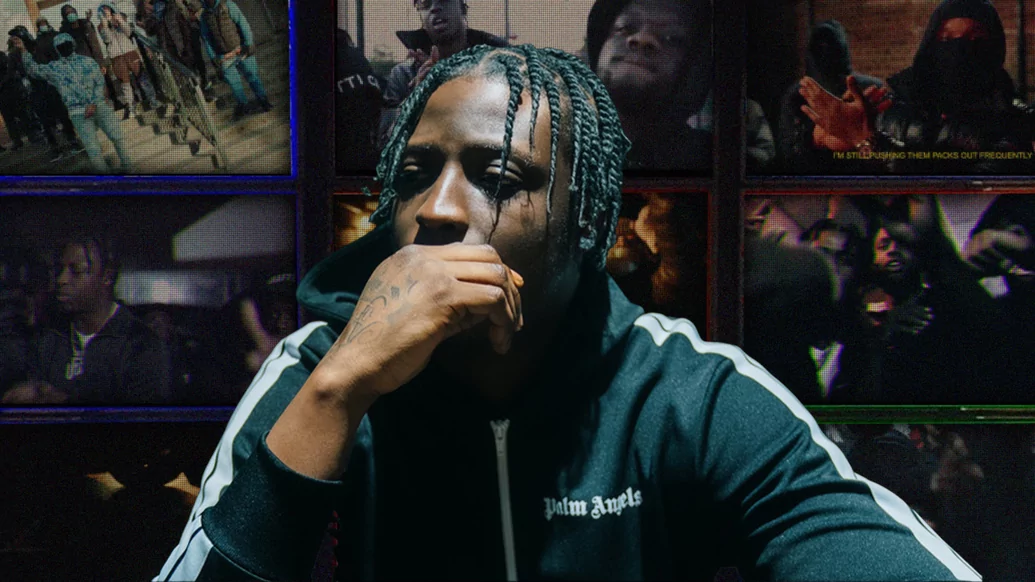

“It was never about, ‘Stop doing that,’” he goes on. “It was about, ‘Please just value your life over likes and streams.’” Of course, all the takedown tactic could really offer was ‘Stop doing that.’ In April of this year, studio engineer and host of the popular Plugged In freestyle series, Fumez the Engineer, told The Guardian that he had tried to open lines of communication with the police over the takedowns, in search of some compromise — but had received no response. Fumez says that takedowns leave him fielding questions that he has no answer to.

“Artists come back to me and say, ‘What happened? I put my time and effort and energy and money and everything into this stuff, what happened?’ And I don't have no answers for them,” he says, a hint of dejection hanging in his voice. A spokesperson for the Met said that the force “works only to identify and remove content which incites or encourages violence; it does not seek to suppress freedom of expression through any kind of music.”

Chinx first released ‘Secret’s Not Safe’ on the 6th of January last year, christening a YouTube channel of his own with the video. “It lasted about three days before it got removed,” he says, “but I wasn’t really too surprised.”

“One of the artists got told they were in imminent danger and they needed to evacuate the area, and the whole conversation had started with ‘We’ve seen a Plugged In with Fumez.’” — Fumez the Engineer

Since coming out of prison in October 2021, having served four of eight years for a firearms offence, he’d been focused on writing and recording as much music as possible. He set out to build a buzz, and knew that being provocative would help him achieve this initially. (A strange quirk of Project Alpha’s approach is that it can have a Streisand Effect: effectively drawing more attention to a track by censoring or removing it. One industry insider even suggests that having a YouTube video taken down can help drive fans to other streaming services, where royalty rates are marginally better.)

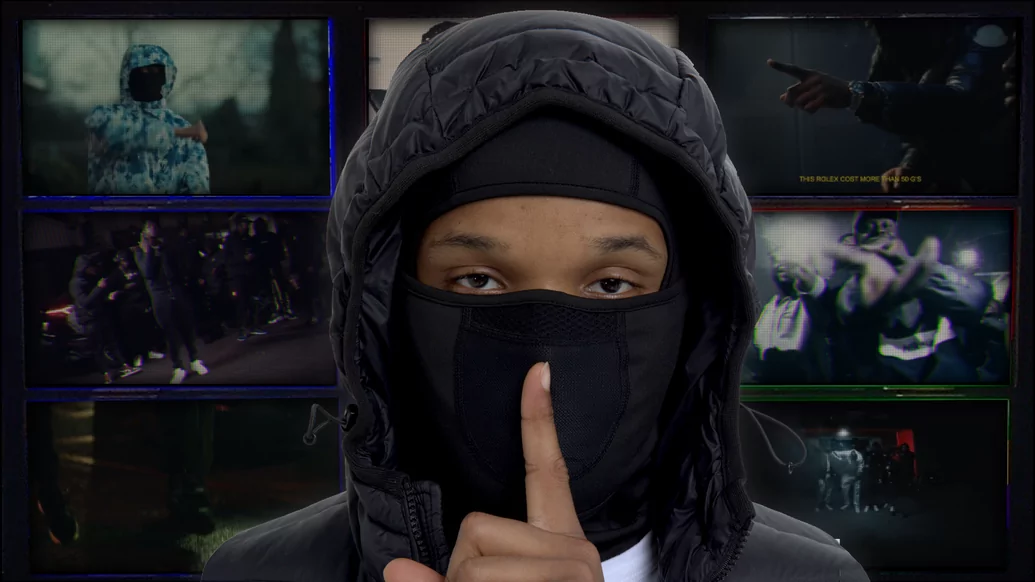

But Chinx also knew that pursuing a music career would involve walking a tightrope of licence conditions: undertaking work without informing his probation officer could land him back in jail. He kept his face concealed in his videos, but was soon fielding questions from the authorities. “Obviously I denied it at first, because I didn’t want them to think I’m not serious,” he says, “and the way it looked from that first song was that I’m just trying to cause a ruckus.”

As his career picked up pace, with a carefully executed rollout of new singles and freestyles, Chinx confirmed the police’s suspicions that it was him rapping behind the mask. “I told them, ‘Yeah, OK, that’s me and this is what I’m doing,’” he says, outlining his plans to make a serious go of his music. “And that’s when the new restrictions came in place.”

Since then, Chinx has been required to notify police and probation services within 24 hours of any new release, and to provide copies of his lyrics when doing so. A further condition prevents him from doing anything that “could reasonably be seen as inciting violence around gang hostility” — a catch-all that it falls to police to define, and could include anything from referencing specific events or individuals to making gun finger gestures in his videos.

This hasn’t stopped him releasing a debut mixtape — February’s gripping ‘One Sided Story’, which cemented his position as one of the drill scene’s most inventive new acts — and seeking out new collaborators. “I just have to find ways to work around it,” says Chinx. “It’s not fair, but I can’t blame anyone. If I hadn’t lived a certain life or hadn’t been involved in certain things, then I wouldn’t be treated in this way. It’s something I’ve just gotta swallow.”

The police’s fixation on drill shows little sign of abating. Fumez details occasions on which artists have been approached by officers about Plugged In sessions that were yet to be published. “One of the artists got told they were in imminent danger and they needed to evacuate the area, and the whole conversation had started with ‘We’ve seen a Plugged In with Fumez,’” he says. “But the video wasn’t even out. They just saw a picture on Instagram of us together.” He struggles to see what good the approach is doing. “They spend money on taking these videos off YouTube, but they don’t spend money on actually helping the youth to better their careers and whatever their hobbies are, or giving them more opportunities and work experiences.”

Set against the broader context of more than a decade of austerity — resulting in crumbling frontline services and a social safety net thinned to the point of splitting — removing rap videos from YouTube in an attempt to curb youth violence looks like yet another myopic policy that throws pennies at the symptoms of deeper-set problems. As Ian McQuaid, Moves A&R and author of Woosh, pointed out recently, “with the global impact UK drill has had, this could have been the closest thing we'd have to K-pop in terms of reach. The Korean government massively invested in its young talent, we... arrested ours.”

Despite his stoicism, the restrictions Chinx is forced to work under weigh heavily. With every taste of success the stakes only get higher: the risk of being sent back to prison for overstepping an invisible line drawn by someone else comes to carry a greater and greater cost. And he knows now that Project Alpha’s officers — with few scruples of their own — will be watching.