Space Afrika: borderless creativity

On their new album, ‘Honest Labour’, Berlin and Manchester-based duo Space Afrika sculpt an experimental electronic sound driven by a desire to break free of genre lines, subtly informed by memories of being young, Black and working class in northern England. Speaking to DJ Mag, the pair discuss the importance of developing artistically on one’s own terms, the influence of Channel U on their ethos, and the beauty of creating undefinable music

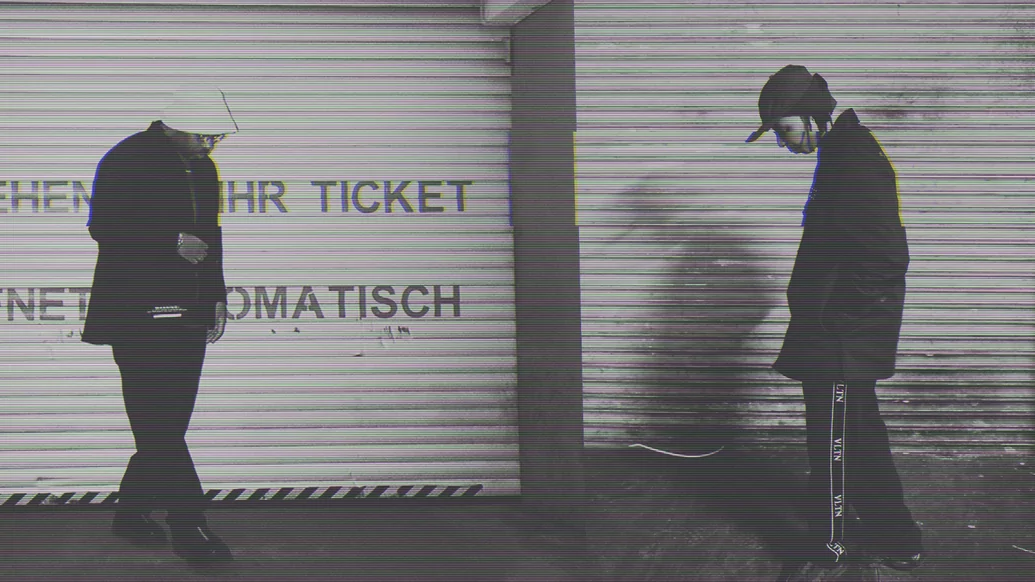

When Space Afrika’s Josh Reidy describes their sound as “borderless”, he means more than the 900-or-so miles separating the city he now calls home, Berlin, from his Manchester birthplace, where his studio partner Josh Inyang lives. Like the pair’s productions, you need to listen carefully to understand exactly where they’re coming from — a futuristic place where spatial atmospheres, heavy low-ends, abstract noises and unique rhythms combine to create entirely new sounds.

Space Afrika’s evolution through the UK’s electronic landscape during the second half of the last decade has been patient. They’ve had select releases on labels like Where To Now?, Sferic and Noorden imprint LL.M., and have played irregular live shows, inviting audiences to escape into their otherworldly soundscapes. Throughout, they’ve occupied a sonic realm entirely of their own: lost in the darkened mist of techno, affected by jungle’s melancholic euphoria; underpinned by the reverberative depth of dub, with layers of ambient floating above. It takes little time to realise they don’t adhere to any easy labels.

“That's beautiful actually, I’m really happy that finally we’re at a point where the tunes aren’t easy to describe,” says Inyang, when we mention difficulty characterising Space Afrika’s work. “For me and Josh, like any artists that strive to continually improve themselves, if your music can be defined, maybe you’re not doing enough with it? Unless that’s what you want. We operate in the experimental underground, right? So to an extent, when you are lifting borders, or when it is impossible to pin-point, that's a good thing.”

Space Afrika’s early output was referred to as dub techno by some critics, but the genre merely provided a jumping- off point for new directions. The likes of Basic Channel, Quantic, Deepchord, Rob Modell, Kassem Mosse and HBL Studios can be heard in certain moments, but rather than emulating those artists, Inyang and Reidy take their lead from the way those producers mapped out uncharted musical territories. It’s an ethos that has expanded to focus on how artists operate and develop identities on their own terms. First and foremost, it’s about ownership.

“We’ve studied how people like ourselves, Black British artists, have been able to become pioneers of a particular sound, or push electronic music forward a certain way,” Reidy says of how Space Afrika has developed into a concept as much as a studio and live outfit. “That was the real learning, rather than being super- engaged in listening to hip-hop, then R&B, then dub. It was more asking: ‘How have these figures moved? What have they put in place? What sort of strategy have they had behind the scenes that has allowed them to be understood better?’”

“You know, paying attention to the basics, watching interviews with Massive Attack and Tricky,” Inyang adds.

One early influence on their approach is British satellite TV music station Channel U, which made household names from the fresh grassroots of grime until its closure in 2018. “Everything is indebted to Channel U,” he continues. “UK music is heavily indebted to Channel U, with the grime, electronic, experimental music that was brewing out of London, Birmingham and neighbouring cities at that time.

“Listening to stuff like Ruff Sqwad, Bomb Squad, Skepta, Boy Better Know — these artists are pioneers of that sound. It’s taken them over a decade to be recognised, but the way they’re influencing these R&B vocals we’ve all grown up on, reworking them into familiar songs with a completely new energy,” Inyang continues. “The readiness and understanding of how to get your sound across, how you have to have a certain confidence, that came from Channel U.”

Manchester also influenced their growth, specifically in relation to what they see as the city’s role as a smaller musical hub compared to London. For the duo, this status frees up artists to focus on their ideas, rather than feeling constrained by industry expectations. “There’s a kind of freedom to be creative in Manchester. There’s not really an overseer trying to control things,” says Reidy.

Plenty has changed since the duo’s formative days. There have been acclaimed full-length releases, such as their 2014 debut on Where To Now?, ‘Above The Concrete/ Below The Concrete’, and 2018’s ‘Somewhere Decent To Live’. Last year saw the release of ‘hybtwibt’, a landmark mixtape in support of Black Minds Matter and National Bailout. Their third album, ‘Honest Labour’, is now due. It’s a record partly informed by recollections of growing up with ears open; of experiences heard in mutated and disorienting forms, longing calls reflected in distant, re- configured vocal samples.

After Reidy moved to Berlin for work, “the only thing you can do is reflect and analyse, to go back to your memories,” he says. Have these reflections impacted their music? “A lot of the memories don’t come from the last few years. They come from 10 years ago, when we were still taking buses and hanging out in Black working class areas. That has started to come to the forefront, which is interesting. It’s not something I really considered before: looking back at certain sounds, which would have been from childhood or growing up as teenagers.”

When speaking about their new label home, DAIS, they respectfully refer to the move as a “graduation”. The goal of ‘Honest Labour’ is to push forward, too: beyond standard musical frameworks and genre lines, and to create agency for themselves. This is the latest waypoint in a grander voyage, destination unknown. “All of our releases are significant. We look back at every release like it’s the most important thing ever and, honestly, I think that’s a really special thing,” says Inyang.

“The ‘Honest Labour’ title is multifaceted, but if you want a direct link to how energy influenced the record, and always will influence Space Afrika, Manchester is a working class city,” he continues. “It’s an industrial city. We’re working class guys trying to build a space for ourselves, with that working class attitude of blood, sweat and tears until you get to your final product.”

“I think the main thing about this whole project is showing that some sounds cannot be defined, it is constantly evolving and moving,” Reidy says. “Our NTS Radio show gives some glimpses of the influences we have been listening to for a very long time. Now, it’s has arrived at a point where you can hear some of those more primitive sounds — sounds which have come before on some releases, and which are labelled as dub or dub techno — but it’s more sincere, bringing back ideas that basically started this musical journey. Now, it’s getting to a point where we can release more, cohesive work that’s not defined under one or two genre brackets.”

It all shows how matured and ambitious the Space Afrika project is — and how, really, this is only the beginning for them.