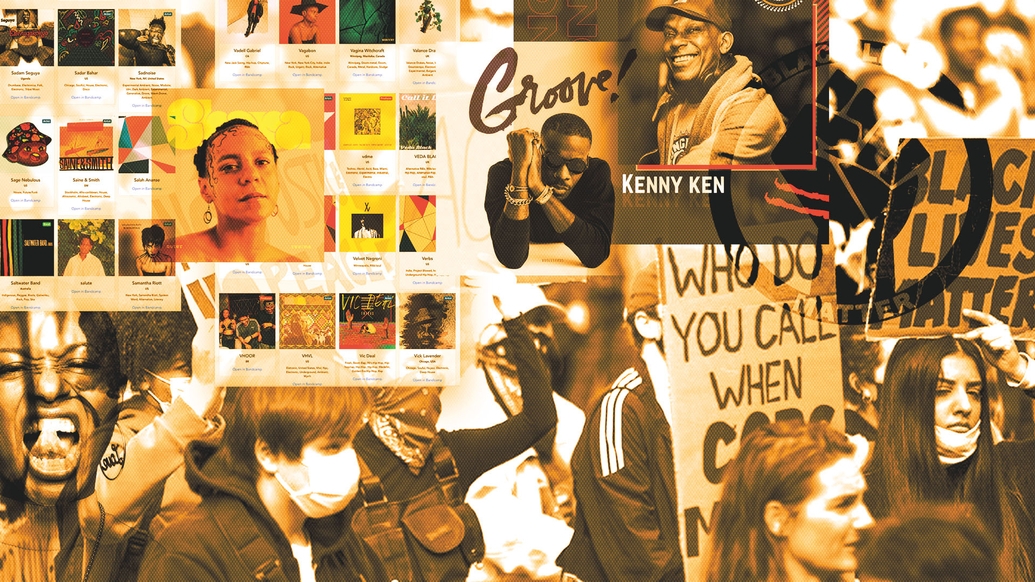

Dance Music Is Black Music: six months on

After the murder of George Floyd in America reignited the Black Lives Matter movement worldwide, questions started to be asked about the lack of diversity in the music industry. DJ Mag produced a special edition of the magazine, Dance Music Is Black Music, which focused specifically on fighting racism within the electronic music scene. Black artists and groups from across the musical spectrum spoke about issues from Black ownership to underrepresentation to mental health. Here, we revisit some of the people we featured in that July issue to see what has changed half a year later.

The Manchester-based DJ spoke candidly with Anz about her experiences in the industry in our July issue. How has she fared since?

The ‘Dance Music Is Black Music’ issue was groundbreaking. It’s still rippling through my circle, coming back through my social media. The way DJ Mag put together that issue — in an open, honest and transparent way, and right at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests — made it very relevant. It’s made a difference and the issue is a keeper, for me.

I had a lot of interesting and positive conversations right after it was published. I’ve always been speaking about racism within the industry, but people generally haven’t been listening. When people read what I had to say in that issue, the moment seemed to present them an opportunity to really listen. I didn’t have a single negative reaction to my interview, thankfully.

I think the momentum around Black Lives Matter has kept up, but I’m like, ‘When all of this is over, when the chatter dies down again, that’s when I’ll know what the actual effect has been’. I’ve seen dance music editorial and radio programming improve in recent months, which is encouraging, but I also want to see line-ups become more inclusive and businesses hiring more Black people.

When it comes to my criticisms of how I’ve been written out of some of Manchester’s dance music history, I don’t think anyone’s going to be literally rewriting the books. But I have had productive conversations with The Haçienda. Later in the summer, they asked me to be part of two major streams they hosted online, and I’m going to be part of their radio station and do other pieces of work with them soon. That’s been a relief.

I would like to think that, in some way, they are redressing the balance and realising that I am as much a part of their history as anybody else. And to be frank, if they’d taken the criticism badly, I wouldn’t be working for anyone, because I didn’t hold back in saying they were part of the problem. But I am very happy and grateful that my criticisms have had the positive effect that I wanted them to have, and that The Haçienda have got the ears and sense of reason and justice to move forward with me in such a positive way.

I am starting to speak publicly now on different platforms, not just as a DJ but as someone deep within the culture. Moving into the field of education has been uplifting and enlightening. I did a session with Manchester Metropolitan University in November in collaboration with FutureDJs, alongside Dave Haslam and Suddi Raval. There was a film screening of Lapsed Clubber, a panel discussion, and a session on the 808 drum machine that included music making and feedback. It’s important to look at our national institutions when it comes to tackling racism in the UK, and being able to speak to students is important.

I’ve also become a patron of the Night Time Industries Association (NTIA), and I’m working on an initiative to deal with changing the culture of sexual harassment within the industry. We want to educate people on how best to offer safe, fun spaces for everyone — from the DJs to the bar staff, the cleaners to the ravers.

Lastly, I’ve been thinking about applying for a culture grant. I curated an exhibition in 2018 for The Lowry in Manchester, and I’d like to tour that exhibition around the UK. Every theme that was discussed in it — sexism, racism, gender inequality and pay gap, mental health, the Black experience — is even more relevant in 2020, so I’d like to explore that more in 2021.

One of the founders of the Radio Silence movement, Kay-Lee Golding, tells us how effective their work has been so far to increase Black representation on UK radio

Earlier this year, two great radio producers, Pulama Kaufman and Sara Hebil-Motie, and I started a movement called Radio Silence. During the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement there were many national UK radio stations posting videos of on-air moments talking about the movement or participating in ‘Blackout Tuesday’ (where social media accounts posted a black square in an effort to give space to the BLM conversation). But to the three of us, this was not a good enough response. It is not enough to treat Black people like a ‘trend’ and to ignore what’s happening in their own buildings. So the Radio Silence movement was created to ask the radio industry: How are we going to do better?

The initial Radio Silence research presented a range of statistics that drew attention to the lack of diversity within the UK radio industry. This included highlighting the appallingly low percentage of staff from minority ethnic groups at the three major broadcasters: Ofcom’s 2019 Diversity & Equal Opportunities in Radio report shows just 9% at the BBC, 8% at Global, and 3% at Bauer. The statistics make it clear that there is a huge disparity in the UK radio industry and that real, tangible steps towards change need to be taken.

Since releasing the research, we have also started a podcast called Radio Silence because we feel that an impactful way to make change is to give minorities in the radio industry a platform to let their stories be heard! The first season focused on Black creatives in the industry. Some incredible voices featured on season one, including Kiss FM’s Tyler West, Capital XTRA’s Remel London, Jazz FM’s Tony Minvielle and BBC Radio 1Xtra’s Shahlaa Tahira to name but a few. On the podcast, the guests discuss their experiences and why representation is so important.

During Black History Month, we saw some amazing content being released across the industry. On episode one of the Radio Silence podcast, Tyler West told us how it felt being able to do a takeover with his dad on Kiss FM, talking about the Black experience. “Never before would I have imagined on a national radio station, me being able to sit there as a boy from South London on a little council estate, being about to sit and talk to thousands of people about the trials and tribulations that me and my dad and every other Black person has had to go through,” Tyler said.

Content like this is so important because it allows listeners to understand the Black experience better and empathise with why we are all fighting so hard for change. During this shift in content programming it is also important to be honest and ask ourselves, without the Black Lives Matter movement, and many other movements for equality, would shows like that have taken place? Maybe not. But the change is starting to be felt and progress is being made.

Each guest also addressed how they think we can make a change in the industry. “If stations want to target and make money from certain demographics, please make sure you’re putting money in the pockets of these demographics as well,” said Remel London, bringing attention to the need to hire producers and presenters who represent the listener demographic. The podcast also featured Steve Parkinson, who is the managing director at Bauer Media. Bauer Media owns a range of stations including Kiss FM, Magic FM, Jazz FM, and Absolute Radio. Since the movement started, Bauer has made significant changes to ensure they have a safe and diverse workplace. For example, they have hired a Head of Organisational Development and Diversity & Inclusion Manager, whose role is to make sure Bauer Media is diverse and inclusive. Parkinson told us that the Radio Silence movement inspired Bauer to sign the Equality in Audio Pact (by Broccoli Content) and said, “It was the best thing we’ve done this year.” We urge other radio stations to do the same!

Radio Silence is not the only movement taking a stand against the lack of diversity in the radio industry. The aforementioned Equality in Audio Pact from Broccoli Content is also doing the same. Their pact lists five actions that will help ensure more diversity and promote equal opportunities in audio companies. Since the initial article multiple companies have signed up to the pact, including BBC Radio, Spotify UK, Bauer Media UK, Prison Radio Association, Mixcloud and many more. We are overjoyed that so much change has taken place in so little time. We know we have a long way to go, but we are all moving closer to the goal of a truly diverse and inclusive radio industry, one conversation at a time.

The BJA formed in the summer to amplify the Black influence in jungle/drum & bass. Akua Ofei explains how it has thrived over the subsequent months

Since the Black Junglist Alliance started in June, opportunities for change have come thick and fast. Editors and designers have now joined, a new A&R department has been created to pick through the flood of submissions to Black Junglist Alliance TV — working alongside our social media team — and, most rewardingly, the BJA has been able to facilitate the signing of a new artist to RAM Records.

Years before Roshan Chauhan’s searing Letter To RA (and the rest of the UK music press), and Marc Mac’s take on the gentrification of jungle, a desire for change in the dance music community has been a recurring theme. Against a feeling that history is repeating when you glance at the state of the current government — where the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, boldly ignores the sprawling graveyard of venues and growing number of ‘plague raves’ — this feels like a good time to reflect on the 30 years of foundation that has been built since the emergence of jungle d&b. The mission is simple: an online library of accurate music history, where the entwined roots of the scene can be understood, and where genres that came after jungle can trace their lineage. It’s a collective history of all the achievements that have been made in one place; fact-checked and accessible. In the cut for any music debate. People will know the history of Sting, Junior Tomlin, Paul Ibiza or DJ Ink, and can learn from them all.

If you’re an artist who wishes social media wasn’t another part of the job and you’d rather focus on making music, why not use the BJA as a channel to amplify your music or feature your achievements? Archives like the Youth Culture Archive and Museum of Youth Culture exist to tell the story of human history and among the many threads of music history, jungle is one.

As we move into 2021, the Black Junglist Alliance will continue to grow our community offline. Scenes don’t live on the internet, they develop through interaction, sharing past times — like record shopping every Thursday. While we can’t bring those times back, we can evolve a sense of community and our Alliance Sessions [on YouTube] serve that purpose. It’s for anyone allied to the jungle sound to make use of, and exists as a place to meet where artists can drop in for a set, test tunes and discover new stuff.

“All the people I met felt like my family — extremely welcoming and good vibes all around,” DJ/producer MYKOOL explains. “[Playing Alliance Sessions] was a very wholesome experience as well as being professional. I love what they are doing and feel so happy to be a part of it. I’m excited for what’s to come!”

Since the beginning of the BJA we have been overwhelmed with messages of help and assistance. We’re focused on developing training and mentoring opportunities with TileYard, and an original merch line will be available soon.

Philosophies will always diverge on how best to go about it and who has the right to attempt a portal such as this — especially when it concerns the hurdles and lived experience of an artist, producer, DJ or MC who has sustained a career for 30+ years. But anyone who wants their chapter written is welcome to do so in their own words. “I like what Black Junglist Alliance are doing,” veteran DJ and reigning soundclash champion Kenny Ken says. “I had a good time on the day doing my mix for them, and I’m looking forward to helping young talent come through into the future of the jungle drum & bass scene.”

NIKS, the co-founder of Black Bandcamp, talks about the success of the project to highlight underground Black electronic music

After our conversation was published in the ‘Dance Music Is Black Music’ issue, the response to Black Bandcamp has been amazing. We had lots of people reach out to us to say they were excited about the project. We have to work reactively across time-zones, which means we’re always busy, but because we’re very community-driven and have people in different continents, it’s been really productive and awesome.

Although we’re a separate entity from Bandcamp, we are in regular contact with Bandcamp’s developers and marketing leads. In the summer, Bandcamp created an invisible hashtag on their website, which generated statistics that showed the impact we were making. On one of the summertime Bandcamp Fridays, over 60% of all the “journeys” to Black artist pages came through Black Bandcamp. They were also pushing us on their socials, but that’s cooled off a bit — I don’t want Black Bandcamp to feel like a sub-entity of their business, we do our own thing.

Things have been going well, but I do have concerns moving forward. When it comes to artists creating music specifically for “Bandcamp Days”, where the artist gets the full sum paid for their release, it’s a tricky situation. Bandcamp is definitely one of the lesser evils when it comes to digital streaming, but it’s still a corporation, and creating music to suit a business plan is weird. We’re in a state of hyper content creation where some artists feel obliged to create music at a volume or pace they otherwise might not have. Then again, Bandcamp are still saying, “Hey you can take all the money directly” — you can’t knock them for it.

Bandcamp had planned to stop the Bandcamp Days in the summer, but they’ve continued throughout 2020 in some part because of our contribution. They’re aware of the impact we’ve had on their business and PR. That’s benefited a community of people who wouldn’t have made much, if any, money from their music this year When it comes to the pandemic, Black Bandcamp started after the pandemic took hold, and it’s only online — we weren’t doing a physical initiative like a club night, so we haven’t had to suddenly move all our operations online to adapt. That’s massively helped with our momentum because we’re not splitting our audience across platforms; it’s all in one place.

I’ve luckily stayed in work during the pandemic, so I’m happy to fund much of Black Bandcamp myself. I know that, during a crisis, asking the public for money is an option when it comes to community-driven projects, but I wouldn’t feel comfortable asking people for money to fund Black Bandcamp right now, to be honest. The pandemic has highlighted just how many serious, life-or-death situations need immediate attention, and we’re definitely not one of those. For now, funding it ourselves is a stretch but doable.

What I’ve been thinking about a lot is how Black Bandcamp can grow while staying community-driven and non-hierarchical. Right now, we are ‘the platform’ for hosting underground Black electronic music online, but I don’t want the wider industry to rely on us to be the one and only, you know? I don’t want us to just be a link you share on Twitter on Bandcamp Days to show that you care about inclusivity, even if you mean it from the goodness of your heart. I want there to be other, similar platforms because I worry about Black Bandcamp being framed as a gatekeeper.

I am thinking of ways to continually decentralise our operations so that we don’t end up running it entirely from an Anglophone, Western perspective. There must be another Black Bandcamp-style project out there, in New Zealand or Japan or Kenya, coming from a different perspective within the diaspora. I’d love to collaborate with them and grow the scope of the genres we cover beyond the electronic ones we currently feature. That’s my aim for 2021.