DJing & the Data Wars: How cloud DJing will transform the industry forever

Data is the new currency and DJing is about to get rich. The endless stream of data generated from cloud DJing will go on to affect labels, artists, producers, agents, manufacturers and fans. We explore the implications of this new data war and what happens when the DJ booth suddenly goes online

It’s the year 2025. You’re having dinner with a friend, and your phone vibrates with a notification — Charlotte De Witte is playing your record, right now, in a club in Tokyo. Through the app, you are presented with choices of what you can do next: watch your track being played live, favourite the moment to watch later on-demand, or follow De Witte’s DJ set to get notifications of the full tracklist, and save it to your own producer profile. Another notification pops up – because you registered with your local Performing Rights Organisation, De Witte’s play of your track has earned you royalties, which have been paid to you in real-time.

All the technology for this situation to be realised, right now, already exists. What doesn’t exist is the infrastructure or business model to make it a reality. We’re going to explore how the new data frontline might play out, the implications it may have for the DJing community, and what happens next.

To understand how we got here, we need to look at developments in DJ technology over the past 18 months. While streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music have been dominating consumer listening habits for almost a decade, the requirement for digital DJs to own tracks (to load on your USB, or play through your DJ software) has meant that downloads are the norm. That also means that, once a track has been downloaded, there’s very little data available to labels and artists as to how that track is being used.

Services like Pioneer DJ’s KUVO and Shazam may give you a very top-level idea of who’s playing what, but with only sporadic pockets of data from users on both platforms, it’s not enough to really inform concrete decision-making or strategy around a release.

Data around streaming, however – be it on YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music or any other platform – has gone on to not only inform countless release strategies, but also shape the way music is being made. The Guardian’s Sam Wolfson argued that “the intros of songs have become shorter to stop listeners skipping a track with a slow build-up. Albums have got longer, often clocking in at more than 20 tracks, simply because listening to a 20-track album generates twice as much revenue as listening to a 10-track one.”

But what happens when this data makes its way into dance music, and specifically, DJ booths? What if you could find out what track was being played in what city, in what club, at what time, and by whom, in real-time? What would be the implications for DJs, labels, producers and club-goers? Let’s explore the answers.

"It could lead to a drop in the fundamental skills of DJing, a lack of cultural awareness around DJing’s core values and a lack of experimentation"

Playlist Power

It’s no secret that getting into some of Spotify’s curated playlists is the holy grail for a lot of consumer-facing labels. So how would that cross over into DJing? It’s certainly not harmful to make it into the Beatport Top 10, nor is it to find your track in a high-profile DJ’s Resident Advisor chart. But their influence, when it comes to reach at least, isn’t on the same scale as being picked for a popular Spotify playlist.

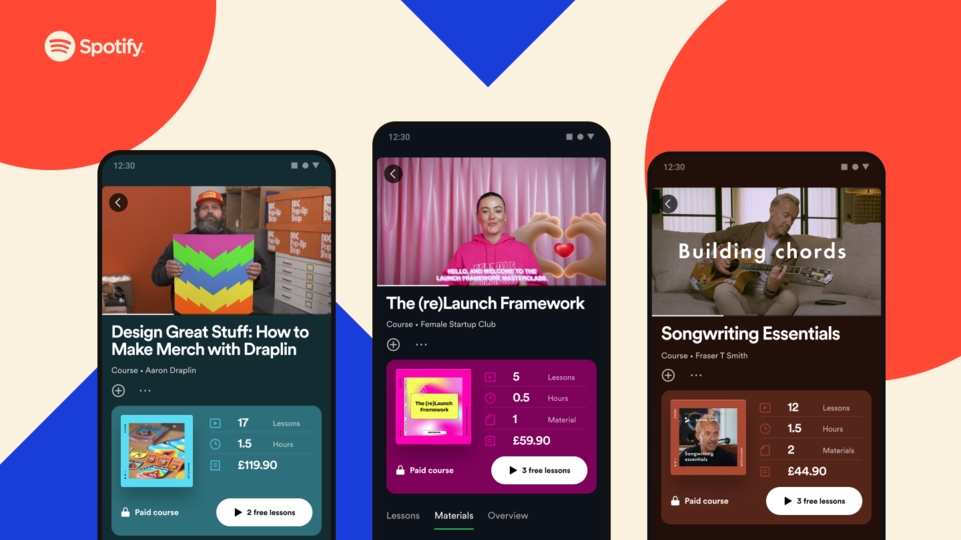

As it stands, DJs are still required to use physical media to play music in clubs. But over the past year, SoundCloud and Beatport, via their new LINK streaming service, have started allowing DJs to stream their catalogues directly into DJ software and hardware.

DENON DJ’s recently announced SC6000 PRIME player has streaming at its heart, with both WiFi and ethernet internet available for streaming tracks from various platforms like TiDAL, Beatport’s LINK and SoundCloud, without physical media required.

Artists have been curating playlist charts for years on Beatport, but with LINK, you’ll be able to access the playlists directly inside your DJing tools. Not only that, but the playlists often reflect an actual set that DJ has recently played, or a vibe or part of the night, like this ‘Warm Up’ playlist from LOUISAHHH! or this ‘Techno Set Starters’ playlist, curated by Beatport. Playlists can also be curated by labels, or even events like Tomorrowland or ADE. Beatport told us that soon users will be able to create and share their own LINK playlists.

Getting into these playlists won’t be the same as breaking into a curated Spotify playlist with millions of subscribers, but it can certainly help. Beatport have yet to reveal what the royalty payments will be for a single stream on LINK, but as we’ve discussed at length in our recent feature on royalties and DJing, a single play at a major festival could be worth £50, and with cloud DJing potentially offering more accurate data for PROs, producers in these playlists could see their royalties increase significantly.

Being able to essentially reach inside your favourite DJ’s record collection, without purchasing or downloading any files, is one thing, but the files are also pre-analysed for bpm and key, meaning you can immediately start testing out some tracks that you’re sure will work together. The implications of such a service could lead to an interactive music discovery service, where not only does machine learning monitor our tastes, but also our DJing style, and suggest tracks appropriately.

It could also lead to a drop in the fundamental skills of DJing, a lack of cultural awareness around DJing’s core values and a lack of experimentation. Without genre-crossing experimentation, this could result in a musically and culturally homogenised generation of press-play DJs.

When it comes to artificial intelligence and machine learning recommending tracks for you to play next, based on your history and the history of other DJs, Beatport have yet to reveal anything on the same scale as Spotify. But with the same feature already present in rekordbox dj – based on your local, offline library – and other DJing software via Related Tracks, it’s by no means a stretch to suggest Beatport LINK could offer something similar in the future. Companies like Echo Nest provide this service already, so a collab here is all it would take.

Eventually, if and when cloud DJing is more widely adopted, we’re not only likely to see recommendations based on what other DJs played next, but potentially where your favourite DJs set their cue and loop points, and at what average point other DJs began mixing out of the track, once DJ mixers become connected to the internet too. DENON DJ’s new X1850 mixer features a “5-port LAN hub” and while no features have been announced around monitoring how the mixer is being used, with the faders and knobs active for MIDI mapping, it’s certainly a possible future feature.

"Knowing exactly where a track is blowing up and gaining local DJ support is invaluable"

So extremely Online

Speaking of hardware, given DENON’s recent announcement, it’s not a stretch to suggest the next Pioneer DJ CDJ and DJM will feature some kind of online connectivity. Despite the obvious streaming capabilities from LINK and other services, the always-on nature of the future CDJ could also offer Pioneer DJ, DENON DJ and any other future player manufacturer to gather data on how their kit is being used.

What’s the most common loop length? What percentage of people are using quantise and Master Tempo? And at what point, for what tracks, do they turn it off? What effect is most popular on the DJM? What percentage of people are using crossfader versus channel faders? GDPR issues aside (quite a large leap here, we accept), the potential data available to manufacturers is going to be a gamechanger for future design and firmware updates.

While playlists and music curation and discovery will be a gamechanger for beginner and hobbyist DJs and data collection from the hardware itself will benefit manufacturers, there are wider implications for this new stream of data for the industry as a whole.

For labels, they’ll no longer be tied to promo downloads and manual feedback from the wider DJ community. Knowing what DJs are playing your releases in real time, and in what part of the world, or tracking what your roster of artists are playing will inform everything from remix packages, collaborations and targeted ads. For A&Rs, it’ll be easy to discover new artists via most-played in certain regions, or spot DJ habits like where they’re looping and where they’re mixing out to inform your feedback on works-in-progress or future studio time.

For agents too, while analytics from social media might tell you where the artist’s fans are based, knowing exactly where a track is blowing up and gaining local DJ support is invaluable for booking a DJ’s next tour, especially if the DJ isn’t as established or the markets are still emerging. And why not book the local DJ who’s been supporting your tracks since the start as the warm-up?

Community

Of all the 1984-style, dystopian connotations this article might conjure up, one of the main positives that will emerge from our data-driven DJ domain is the community that will develop around it. As we mentioned previously, the idea of an app on your phone pinging you when a DJ you admire plays your track might be a gimmicky cause for another round of drinks, but the real-world benefit comes when it’s not so much a famous artist, but a local, grassroots DJ supporting your music. The implications are huge from booking swaps, remix swaps, remote studio collaborations to even just DMing to say thanks, creating an instant connection that wasn’t possible before.

Creating an independent community based around organically supporting each other’s music is extremely powerful, at a time when producers can feel like they’re screaming into the void and are lost in the noise. Of course, this community already exists to an extent and countless collabs, partnerships and friendships having been built via online connections, either dropping a DM or a Facebook message. But the global scope of the data delivered by cloud DJing, as well as the automated nature of it, will flag so many more opportunities for emerging artists and labels.

A new app called Seeqnc teases what this potential future community might look like. The app ‘listens’ to your set through your phone, identifies what’s being played and shares it with the artist, if they’re also using the app. Without a global audience it’s off to a slow start, but the premise is there and the interface isn’t a million miles away from what you’d imagine an automated service would eventually look like. Try it out here if you’re curious.

Open at the Source

There are a number of potential, and large, stumbling blocks that might make this utopian-slash-dystopian world a reality. Currently, services like Soundcharts that scour the internet to find out where and how your music is being used, rely on open APIs to get their data. They combine social media accounts, streams, views and so on to give the user a picture of their online presence via open APIs from Spotify, Google, etc. But for things like radio play, of which data is not publicly available, they pay for it.

Dmitry Pastukhov, Junior Brand Manager at Soundcharts told us, “If you can go and manually look up the data yourself, it's going to be accessible through [an] API. If not, someone sells it out there.” It will be up to Beatport and Pioneer DJ to decide if it’s more valuable for them to hold on to the data to shape their business decisions, or to charge their users to access it, probably through a subscription tier. Or a bit of both.

There’s also the extremely obvious problem of privacy, not only from a GDPR perspective — track ID culture is one of the most divisive topics in electronic music, with DJs having covered up the tracks they’re playing ever since they played them. Whichever mantra you subscribe to, there’s no doubt that the idea of broadcasting exactly what track you’re playing, and where you’re playing it from, is going to rile up a huge portion of DJs. Consent will be a huge part of how these services are rolled out.

And of course, not everyone uses digital formats — while music recognition technology can also identify the track and location of a vinyl record, the data is strictly private for PROs, so wouldn’t apply to a global database. For now.

Where do we go from here?

While the vast majority of this article is hypothetical, there are already glimpses of this data-driven future starting to appear across the DJing industry, not just via DENON DJ’s new SC6000 player but apps like Seeqnc we mentioned before. None of it is a wild stretch of the imagination, more it’ll rely on cooperation of DJ manufacturers, with DJs themselves opting in, before any of the affects can be expected.

Given manufacturers’ track record for cooperation — and the often chasmic differing viewpoints across the DJ community — that might be too big a stretch to see these concepts fast-tracked. It’s possible too, that there are no positives in any of these developments, and that creativity could be hampered, track choice could be amalgamated, charts and playlists could be gamed, data could be manipulated.

A counter-culture could also form; anti-digital, anti-data, anti-cloud and pro-privacy, where fundamental mixing skills and diverse selection are cherished further. Whichever side of the fence you sit on, it will be fascinating to see how it plays out.