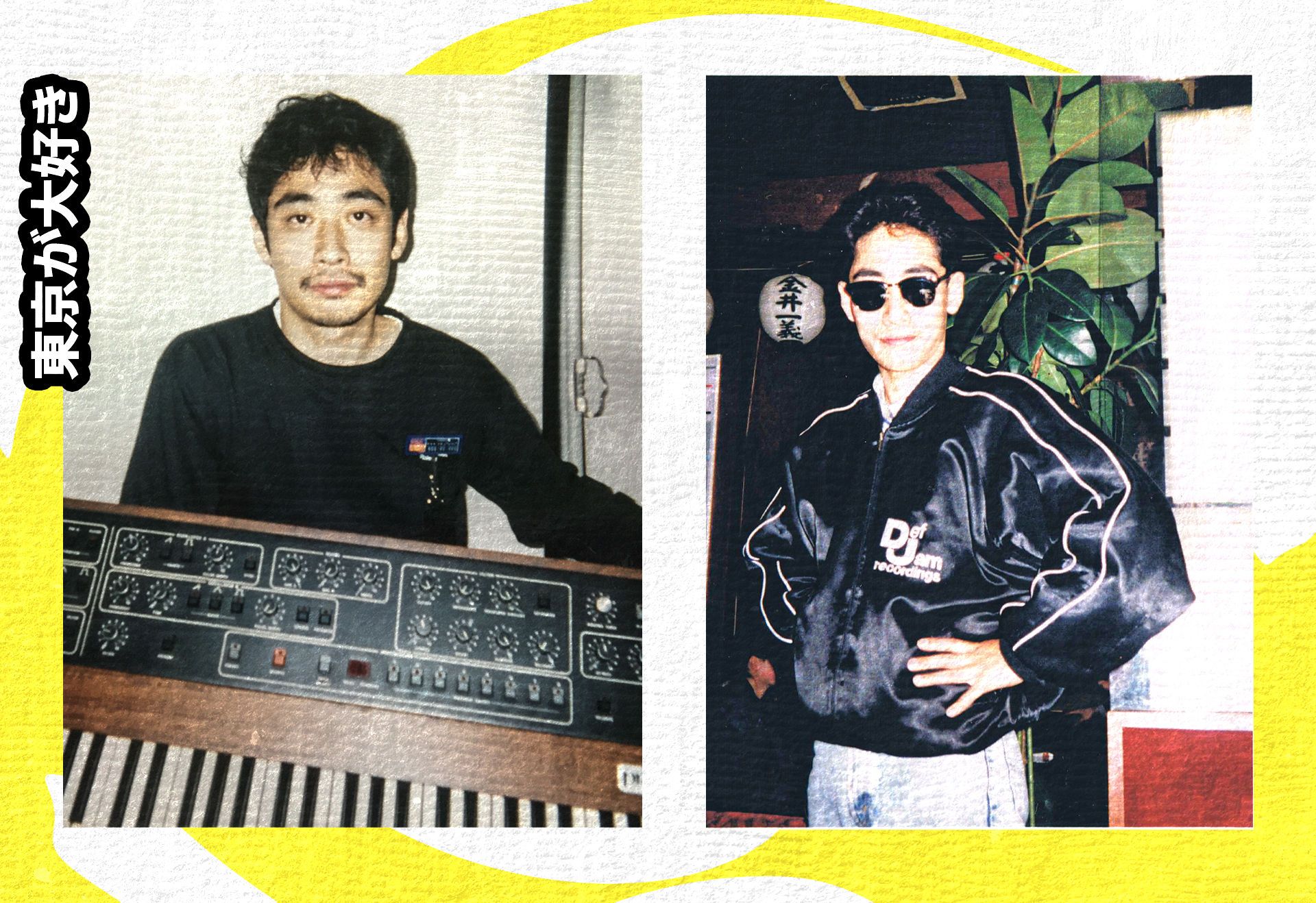

The driving force of Shinichiro Yokota and Soichi Terada

Tokyo’s Shinichiro Yokota is one of the great unsung heroes of house music, though thanks to a particular YouTube video and a new Sound Of Vast compilation, that’s starting to change for the better. DJ Mag meets Yokota and his musical mentor Soichi Terada in Japan’s capital, to talk about cars, overseas success, and their longstanding friendship

This October, Amsterdam-based, Japanese record label Sound of Vast releases ‘Ultimate Yokota 1991-2019’, a compilation album of previously unreleased music by Tokyo house producer Shinichiro Yokota, spanning three decades of his career. Early tracks, like ’91’s ‘Night Drive’, pair ebullient piano work with pared-down rave sensibilities. True to its title, ‘Night Drive’ conjures up images of cruising through bubble-era Tokyo and partying in legendary nightclubs like Juliana’s, where hedonistic, suited-up businessmen would drink champagne and then flag down taxis home with 10,000 Yen notes.

Some of the compilation’s more contemporary tracks, like 2019’s ‘Tokyo 018’, are collaborations with Yokota’s long-time musical partner Soichi Terada. Compared to Yokota’s early solo work, these collaborations sound more polished: a colourful patchwork of interweaving synth melodies and arpeggios, love notes to the capital; ‘Tokyo 018’ features a sample of a man exclaiming “Watashi wa Tokyo suki” (“I love Tokyo”).

Between these two tracks, spanning a period that has seen both Japan’s capital and its musical landscape undergo transformational changes, lies the story of Shinichiro Yokota in three interwoven chapters: a seemingly irreconcilable passion for both cars and electronic music, his life in Tokyo, and his friendship with Soichi Terada.

“I’m happy to meet you anywhere, as long as there’s a car park nearby,” Yokota tells us. We settle on a cheerful Mexican restaurant in the Nakameguro neighbourhood of Tokyo, and he arrives early in his car, having picked up Terada along the way. His car, one of two that he owns, is a sporty BMW that’s been customised to ride lower to the road. Its chassis barely passes the metal plate that sticks out from the parking space, a common mechanism designed to ‘trap’ cars until payment, the first hint that this vehicle is not meant for Tokyo’s narrow residential streets.

It’s impossible to talk about Yokota without talking about his love of cars, which permeates the world of his music. From photos of him in the driver’s seat on release artwork, to track titles like ‘Night Drive’, it’s clear that one passion informs the other. “When I wrote [1993 track] ‘West Gate’, I had meant to title it ‘Wastegate’, a device used for turbo-charging cars, but I got the spelling wrong and it ended up with a much less exciting name,” Yokota recalls with a laugh.

He drives everywhere, and he does it quickly, too. “How long did it take you to get back from Star Festival?” Terada asks Yokota, referring to a small electronic music festival in Kyoto where the two had performed the previous year. What time did we finish up, around six or seven in the evening, right? I think I was back at home and sipping on a beer by 11PM,” he answers, making light of the near-500km journey.

A cross-country drive might be one thing, but his cars are the reason that you probably haven’t seen Yokota perform live outside of Japan. He’s been running his own custom car parts company, Night Pager, since the early ’90s, specialising in tuning sports cars and modifying limiters for competition racers. It’s a demanding full-time job, but this has never been a problem for Yokota. He speaks passionately about it all, but it also presents a dilemma.

Now, he’s increasingly in-demand by clubs and festivals overseas, having been exposed to new audiences en masse through ‘Sounds From The Far East’: a 2015 compilation album of Terada and Yokota’s early work, compiled by long-time fan Hunee especially for Rush Hour. Whereas Terada has always primarily worked as a musician, and has been able to embrace the international opportunities that have come from his resurgent popularity at a relatively late age, Yokota has had to turn down offers to play at renowned institutions around the world.

He recalls having dinner with a man that was explaining keenly, through a translator, that Yokota should play at Panorama Bar, but given his work commitments, to no avail. He tells this story not with regret, but with a cheerful mixture of pride and surprise that he would be invited in the first place. “When you look at the DJs and producers from Japan that are touring abroad regularly, it’s a very short list,” Yokota says, name-checking the likes of DJ Nobu and Gonno.

“I feel very grateful to even be in that company, and I would be happy to perform abroad one day, but for now I’m going to focus on playing in Japan. And it also makes it more special for the people who come to visit Japan from abroad, people who come to see me play at my gigs here.”

Terada, who must be vying with DJ Nobu for the prize of 'most air-miles earned', listens quietly. His expression makes it clear that he would love for Yokota to have the experience of playing overseas, as he has done, and he suddenly becomes more animated. “But what if there was a huge earthquake in Japan, and society was brought to a halt, chaos everywhere?”

Terada ventures, his eyes lighting up. “And the country was in ruins, and there were mobs of gangs roaming the streets, like in Mad Max. Then you’d be able to take a year off!” Yokota laughs at the notion, but his priorities are clear, at least for now. Earlier, he had remarked, “I don’t listen to music when I’m driving. I listen to the sound of the engine.”

As Terada’s production abilities developed, he struck upon a style of his own, and it was at this point that Yokota met him and set about the curiously postmodern task of copying a copy without an original. “I would drive to Terada-San’s apartment and watch him make music late into the night...” he says. “I would... stay up, repeating what I had watched him do, even if I had to be up for work in just a few hours.”

The neighbourhood we are eating in, Nakameguro, is relatively newfound in its popularity among young, fashionable Tokyoites. It’s an area symptomatic of the sort of understated gentrification that affects the capital, which might usher in jarring infrastructural developments like a colossal, Kengo Kuma-designed Starbucks roastery, seemingly overnight, but rarely brings stories of forced displacement or the fracturing of communities. It is not uncommon for people from the city to comfortably remain in one neighbourhood for their whole life.

For Yokota, that neighbourhood is Ota, a ward in southern Tokyo that is also home to Haneda airport. Yokota has lived in Ota all his life, and Terada, similarly, a short drive’s distance away. The two first met through a mutual friend in their late teens, and they quickly bonded over music. At the time, Yokota would mostly go out to hip-hop events; he discovered house music through Terada, who had himself been inspired by the likes of Larry Levan and Victor Rosado in New York, and who had first set out wanting to replicate the Paradise Garage sound.

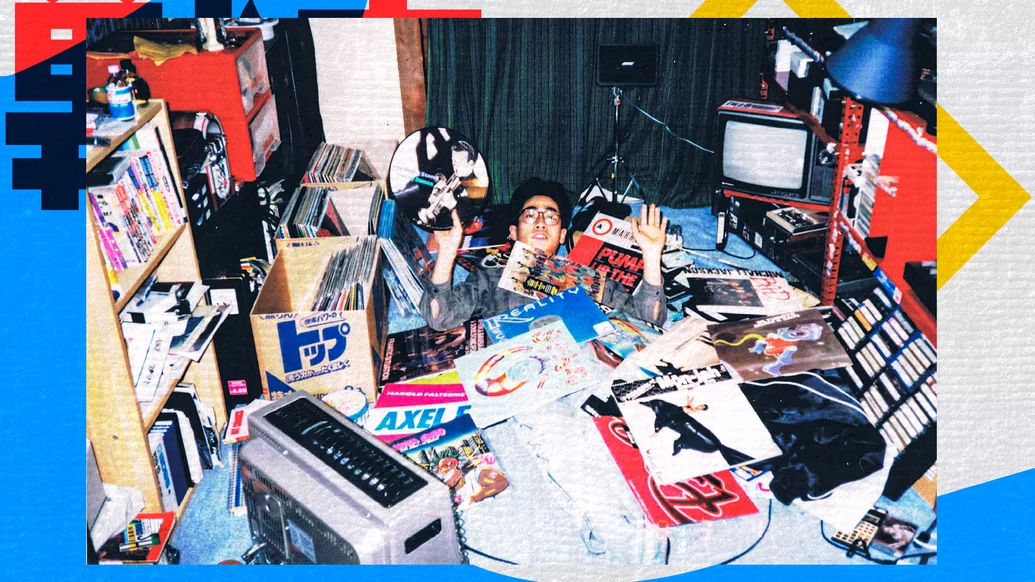

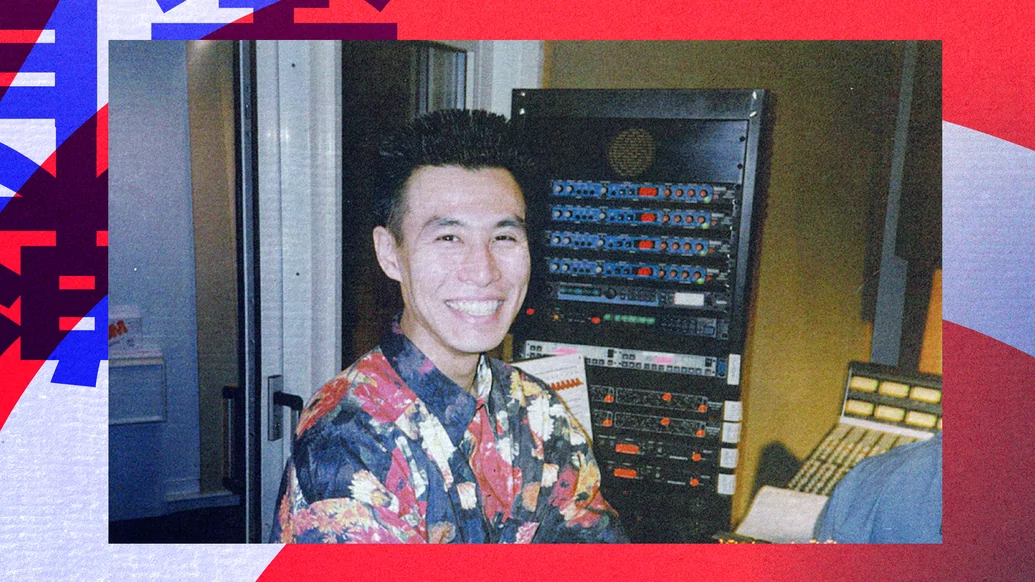

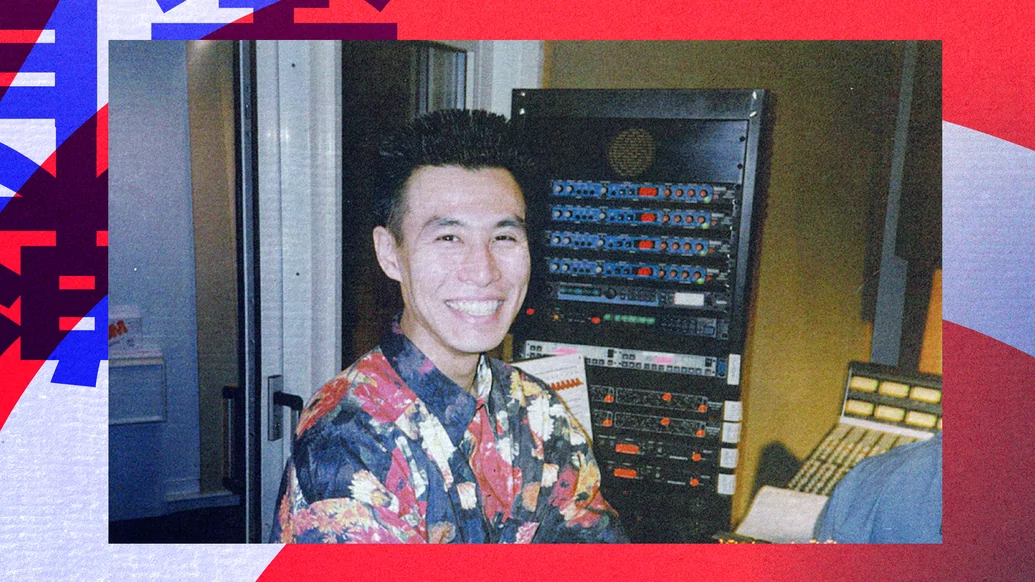

As Terada’s production abilities developed, he struck upon a style of his own, and it was at this point that Yokota met him and set about the curiously postmodern task of copying a copy without an original. “I would drive to Terada-San’s apartment and watch him make music late into the night. I was inspired by how skilful he was, and there was so much for me to learn,” he says. “I would get back home in the early hours of the morning and I’d still stay up, repeating what I had watched him do, even if I had to be up for work in just a few hours.”

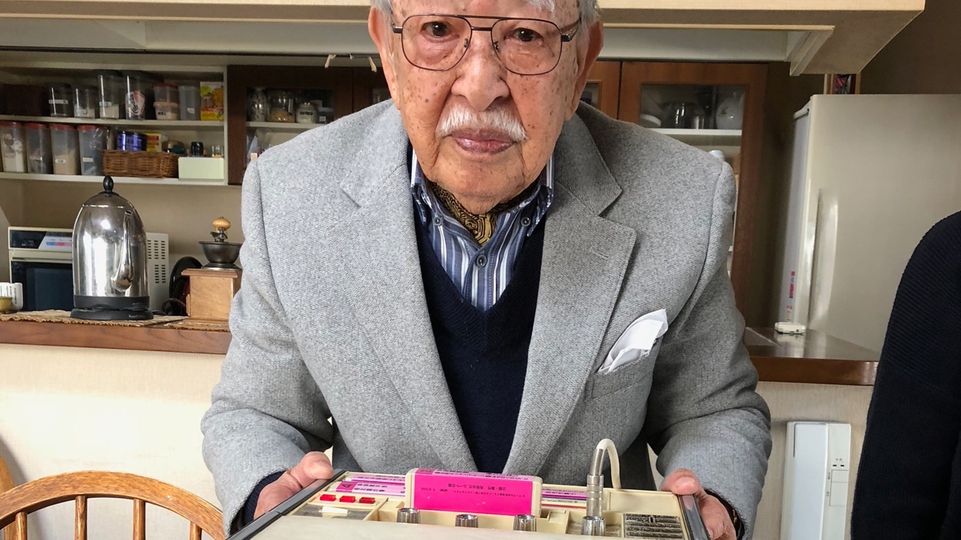

Today, still, Yokota draws on the same diligent approach in his other musical venture, a cover band for one of Japan’s most legendary electronic acts. Once a year, Yokota and his friends perform live in a tribute to Yellow Magic Orchestra, and they do so by faithfully sourcing the exact equipment that would have been used originally by the group.

“Each year, we try to mimic the evolution of YMO at the time,” he explains. “So if they had started to use new gear, we’ll update our setup accordingly.” If any budding music producer were to attempt the same exercise 20 years from now, but for Yokota’s own back catalogue, they would have a much easier time. Little has changed between his early-’90s work and the newer tracks on ‘Ultimate Yokota 1991–2019’, for which he still draws upon staples like his Rhodes piano, Korg M1 synthesiser, and Akai sampler.

These days he also uses digital software like Logic Pro, which adds a layer of sheen to his productions, but detracts little from the natural warmth Yokota continues to create through his grooves and melodies. Its warmth is mirrored in his character, as it is in Terada. Both men have a generosity of spirit that they extend to every person they meet, and this record, also, is born from such a gesture.

“I was getting messages from lots of DJs overseas that they wanted to play the tracks on my CDs and SoundCloud, but they only play records, so I put them all together in a vinyl release,” Yokota explains. Even the album art, depicting a yukata-clad, cyborg Yokota, was created in the same vein. “I get the impression that Japanese cyberpunk like the movie, Akira, is very popular abroad, so I thought people might like it.” Now, with Tokyo 2020 on the horizon, Yokota will turn his attention back to his hometown of Ota.

Like many of Tokyo’s other wards, Ota is expected to see an influx of international athletes and spectators during the Olympic period. As well as helping with plans to develop more lodgings to cope with the spike in visitor numbers, Yokota is working on kitting out local park, Furusatono-Hamabe, with audio facilities, and turning it into a cross-cultural party spot for tourists and locals. For all the talk of international tours and overseas travel, one gets the impression that Yokota would be just as proud to play a little closer to home.

On the inlay of ‘Ultimate Yokota 1991–2019’, there’s a message of support from Terada that ends, “...you who get this record will be reaffirming the beautiful sound that Shinichiro Yokota is creating. And Shinichiro Yokota, you ‘Did it Again’!” The line is a reference to ‘Do It Again’, a track originally released in ’92 as a B-side on a record titled ‘Far East Recording’, and released on Terada’s imprint of the same name. It is, simultaneously, the track that Yokota is best known for, and for which he has been the most overlooked.

Six years ago, the track was added to YouTube by ‘UtopiaSpb’, a generic-looking account that uploaded just under a dozen house and techno rips around the same time, and has been inactive ever since. While view counts for the other videos registered to the account all sit in the low-thousands, ‘Do It Again’ has surged into seven-digits, an example of the sort of algorithmic serendipity that has similarly played a significant role in resurfacing decades old Japanese ambient and jazz.

But there was a snag — the title incorrectly credits the track to Soichi Terada, not to Shinichiro Yokota. Terada himself left a comment on the link years ago, pointing out the inaccuracy. As someone who regularly performs the track in his own live sets, Terada was aware that people could easily mistake it for one of his own compositions, and was keen for Yokota to be properly credited. But the title was never edited, and the video continues to consistently churn through hundreds of thousands of new views every few months, propelled by the platform’s algorithms, but also the track’s innate quality.

Simple and catchy, ‘Do It Again’ features a trademark seven-note refrain that sits over a warm and gentle synth line, occasionally giving way to a melodic flourish of piano chords. Like all the best house music, it is universal in its appeal, the sort of track that would delight anyone and everyone, and it’s unsurprising that it continues to find new audiences.

Nonetheless, Yokota is amazed by this phenomenon. He acknowledges every numeric milestone with a post to his own social media. The day after we meet, he posts that the link has recently hit two million views. It’s the epitome of what Terada and Yokota do best, but the magic of the track is distinctly Yokota, in his choice of sample: a woman’s voice saying, “Hi, EZ-Q? It’s me, Sara Jane, I was wondering if you’d like to do it again?”

Taken from a Derek B track titled ‘Good Groove’, the original recording is husky and seductive, but Yokota pitch shifts and plays with it, imbuing the speaker with a mysterious essence that is as essential to the track as any of its other elements. His instinctive ear for the perfect sample harks back to his formative years listening to hip-hop, and ‘Ultimate Yokota 1991–2019’ is littered with proof of that. Tracks like ‘This Moment’, ‘Right Here! Right Now!’ and ‘I Know You Like It’ are all elevated through the deft touch with which Yokota employs vocal samples.

“I don’t understand English, so I never really know what they’re singing about,” he says. “I pick out samples based solely on the musical quality of the vocals.” The process isn’t entirely fool proof. A suggestion that there might be a double-entendre on ‘I Know You Like It’ has Terada and Yokota giggling in embarrassment, as they understand what it could potentially mean for the first time. “Just as well you weren’t singing it,” Terada quips.

The friendly exchange is just one of many between the pair during the course of the evening. Terada is Yokota’s senpai; his senior in age, and this is reflected in Yokota’s use of the honorific suffix “san”, which he attaches to Terada’s name. But in this case, it feels far removed from any sort of hierarchical distancing, and rather a natural extension of the mutual respect that underpins their relationship as friends and collaborators.

“I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Terada-san. He’s the only reason that I’ve been able to succeed with my music,” Yokota says, as Terada shakes his head, contesting the validity of the statement. “With this record I even copied Terada-san’s compilation, with the double vinyl, gatefold sleeve and liner notes in the middle, and it’s a dream come true to have been able to release this.”

Then, Yokota turns directly to Terada and tells him, “I’ve never known anyone who can make an audience smile like you do,” to which Terada can only smile. It’s clear that Yokota would be delighted even if his music was forever associated with his friend Terada. But as is increasingly the case, and which the release of ‘Ultimate Yokota 1991–2019’ will only reinforce, Yokota deserves to be acknowledged as one of Japan’s finest purveyors of house music in his own right.