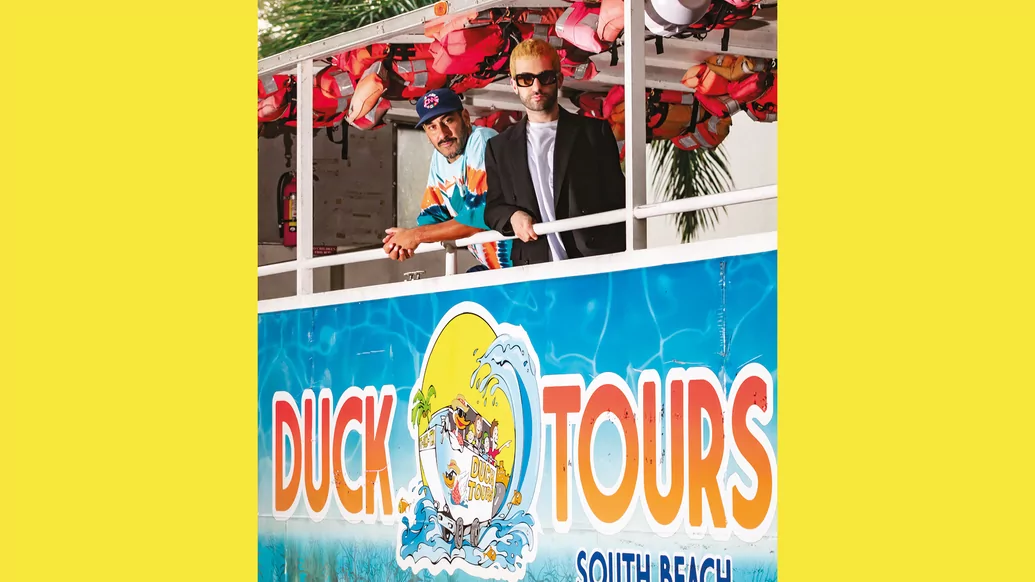

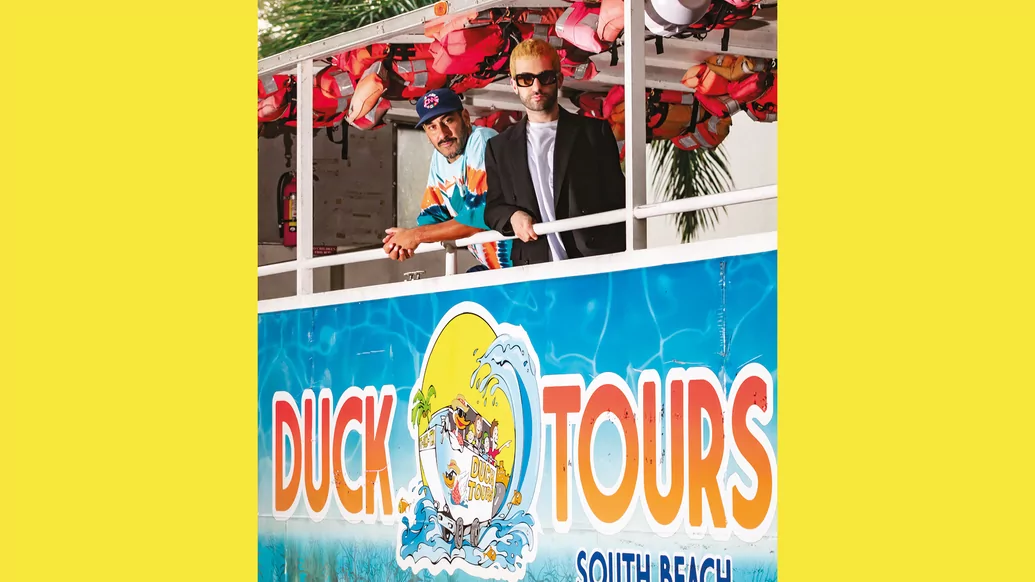

Duck Sauce: Return of the quack

Avian accomplices Armand Van Helden and A-Trak are Duck Sauce — the fun-loving duo behind house mega-hit ‘Barbra Streisand’, as well as countless underground club smashes under their own names. Ahead of their appearance at our Miami pool party and a slew of new material, we take a duck bus tour with them in the city, and get a glimpse into their weird and wonderful world

It’s hot in Miami as the Duck Tours vehicle leaves its Lincoln Road ‘duck stop’ with a smattering of tourists onboard. “For your safety, please keep your hands and elbows this side of the white railing...” drawls Sam the tour guide, a middle-aged black man with the patter of a holiday camp entertainer.

As the cumbersome but functional bus/boat pulls onto Washington Avenue, Sam gets everyone to go “Quack, quack, quack”, starts asking where people are from, and pointing out grandiose Art Deco buildings. Nonchalantly lounging at the back of the bus are two multi-awardwinning DJ/producers, who give their names to DJ Mag as Charlie Chaz and Rappin Ralph. “Those are our names for now, but we’ll get some better ones,” quips Charlie, aka Armand Van Helden, multi-platinum house music genius and all-round good egg.

DJ Mag is hanging with Armand and A-Trak, who together are Duck Sauce, the multi-million-selling DJ act best known for wonderfully camp disco-house ditty ‘Barbra Streisand’. After a hiatus of a few years, the duo are returning with a raft of new tunes and a whole bunch of shows lined up — including the DJ Mag pool party at the Surfcomber in South Beach on Wednesdy 18th March during Miami Music Week. Duck Sauce are quack!

The individual achievements of both of these DJ/ producers are considerable. A-Trak, famously, at 15 was the youngest-ever winner of the DMC Championships, who went on to be Kanye West’s tour DJ, start his own Fool’s Gold label, and rock the EDM festival circuit continuously. Armand, meanwhile, is the genre-busting house music legend that is widely regarded as a pioneer of speed garage, has scored several global No.1s, and now lives in Miami in an airy apartment overlooking the sea.

Armand lives here full-time now, having spent a few years being a ‘snowbird’ (someone who travels to warmer climes for winter) between New York and Miami. When hanging with Armand at his apartment the previous day, your DJ Mag hack was warned about the comedy banter between him and A-Trak when they get together. “It’s like improv,” Armand had said.

“We’re goofballs. When the two of us are together, something happens, we just fall into our little world. I think that’s why people hear a spark when we make records together, because we’re having fun, and that emotion gets imprinted in the music” — Rappin Ralph, aka A-Trak

But nothing could’ve prepared us for just how surreal their duck-tastic goofball exchanges were going to be onboard the Duck Tour, one of the most bizarre interviews your seasoned DJ Mag writer has ever conduckted...

A short way into the Duck Tour, we ask what the guys think of it so far. “We feel at home,” smirks Armand, leaning back satisfied in his seat. Is their plumage still intact? “We groom each other with our beaks,” says Rappin Ralph, aka A-Trak. “Before we made any music, we groomed each other.”

As we drive up Washington, Sam the tour guide starts talking about Cuban-American singer Gloria Estefan, and when she auditioned for a wedding band. “The wedding band later became what band?” he asks the tourists over the mic. “Miami Sound Machine!” shouts Armand, his wealth of musical knowledge coming into play.

We’re soon heading onto the MacArthur Causeway bridge that connects South Beach to downtown Miami, and Sam points out the exclusive and private Star Island where multimillionaires like David and Victoria Beckham and actor Nick Nolte have big houses. DJ Mag asks if the guys have their own Duck Island. “We own a duck island in The [Florida] Keys,” claims Armand, “but it’s very, very secret. There are beautifully-arched bridges on it, and canals...”

“We’re famous for our Mediterranean-style arched bridges,” continues A-Trak. “And jazzercise classes.” “Our Duck Island is two miles wide, in the shape of a duck,” adds Armand. “It was shaped like that by Mother Nature, and by house music — a lot of kick drums over the Millennium. Vibrations. When the kick drums stopped, it was in the shape of a rubber duck.”

Having Fun

A decade ago, Duck Sauce premiered ‘Barbra Streisand’ at Miami’s fabled Winter Music Conference (WMC). It went on to become a worldwide hit. DJ Mag wants to know if Babs’ people ever got in touch with them about the track. “We have never met Mother Barbra,” affirms A-Trak. “Yet.”

“But we got good confirmation — from his side and my side — that she loved the song,” adds Armand. They start talking about Barbra Streisand’s allegedly cloned triplet dogs. “That’s why we honoured her, she respects the animal kingdom,” says Armand.

The guys say they don’t know what they’re going to debut this year at WMC, out of the plethora of new tunes they’ve made recently. “We make a bunch of tracks, and we never know which ones are gonna resonate,” says A-Trak. “The flock chooses.”

As the bus/boat ducks into the water, Armand exclaims: “This is what all cars should be able to do.” He starts talking about how Duck Sauce are going to be dropping new tracks “every moon cycle”, and that apparently ducks turn into mean beasts when there’s a full moon in the sky. “Their teeth come out,” says A-Trak. “They don’t turn into werewolves,” adds Armand. “It’s worse than that.”

It’s pretty clear by now that the duo, while not exactly ducking any ‘serious’ questions (or otherwise), are chiefly going to be refracting their answers through the prism of imaginary ducks. Some of their phrases are perhaps masked metaphor; most of it is seducktive psychobabble that’s either smart stoner humour without the great fogs of weed smoke, or utter gibberish. Or both.

What’s evident is that none of this banter is scripted or rehearsed — they’re completely freestyling. Quite obviously great friends, when the two of them are together they fall into an alternate reality that’s all it’s quacked up to be, and more. Their sense of having a laugh, mucking about and not taking themselves too seriously clearly extends to their modus operandi when making tunes in the studio.

Luckily, we interview them separately as well. “The whole thing is fun,” concurs Armand the day before the Duck Tour ride. “A-Trak’s fucking hilarious first of all, and our whole thing is just having fun in the studio really. Making the initial parts of a track is super-fun — the first few hours are always the best. That’s when we’re excited or happy or laughing, or ‘That's cool’, or ‘We love this groove’. I wish music was that simple, but it isn’t.”

A-Trak is on record as saying that he rolled around the floor of the studio laughing for 15 minutes after they made ‘Barbra Streisand’, with its camp Boney M sample and spoken word Babs homage. Have any of the new Duck Sauce tracks had him similarly rolling around? “Yeah — ha ha!” he affirms when we interview him later.

“We’re goofballs. When the two of us are together, something happens, we just fall into our little world. I think that’s why people hear a spark when we make records together, because we’re having fun, and that emotion gets imprinted in the music. It informs our choices. We’ll pick samples that make us laugh.”

Sample Fiends

Armand likes to tell the story of when the friends hit the studio together for their first collab. “I remember he was sitting on my couch and I was on my chair, and I turned to him and was like, ‘So what are we doing?’ He’s like ‘Disco house’, and I go ‘OK’. I turn right back to my computer and start looking at my disco samples and my old drums — literally, that was it.”

“I always thought the filter disco French house sound from the ’90s was cool,” says A-Trak. “To me, it spoke to my hip-hop ear. It’s samples, it’s tracks made on the same samplers as the hip-hop records that I love. And Armand had the record collection. I didn’t necessarily know which records to sample, but I knew he’d know.”

Armand is a real sample fiend, sometimes spending seven or eight hours a day skipping through tracks during “vinyl digs”, almost giving himself carpal tunnel syndrome. He tells DJ Mag about a little adjustment he made to his deck’s tone arm, involving a tiny elastic band and “a toothpick kinda thing” to rest his hand on during these record-skipping sessions so that he didn’t get some form of repetitive strain injury.

“A lot of these disco samples don't sound good to begin with, so we have a lot of trickery that we’ve crafted, through sampling, to cheat, and we’ve found all kinds of things,” Armand says. “I’m not going to give up any of those secrets, but we find ways to make the disco sample sound way better than it is. That’s work, it takes work to do that, you know? Basically, it’s mixing and making things sound good — it’s going to war with the song. These are the worst days, but the first few hours of creation are just the most joyous things ever.”

“More than half of our samples aren’t disco, but have the spirit of disco,” A-Trak adds. “Disco is euphoric, disco is pure joy — so that’s the spirit of Duck Sauce. Pure joy, and ear-worms — just looking for these little loops that have an ear-worm. If we find a sample and it gives us that little tingle, we know it’s gonna have the Duck Sauce feel. Half the time it’s not disco, it might be an ’80s rock record, or new wave — we sample a lot of new wave.”

The ultimate ear-worm was ‘Barbra Streisand’, wasn’t it? “We had no idea it’d be an actual chart record,” says A-Trak. “We thought it was a B side. We knew it was funny, but literally I remember playing it to my friends and prefacing, ‘Hey, do you wanna hear this really silly thing that Armand and I did?’ Then I’d test it out at shows and everybody would be singing along.”

“Yeah, it was such a surprise for everybody when that song became a big hit,” adds Armand. “For me to be involved with a song that an eight-year-old kid wants to sing blew my mind. Man, life’s a funny thing, because life wants to show you some weird shit. I did not know from my roots — growing up listening to Pal Joey and Bobby Konders and Kenny Dope and Todd Terry — that I’d make a song for Disneyland, you know what I’m saying? I mean, fate is a crazy, crazy thing, but the thing about it is, I’m all good with it, you know?”

Hip-Hop To House

To much of the new generation of EDM fans, Duck Sauce are just two guys goofing around. But both have considerable storied pasts that are worth delving into a little. They haven’t been elevated by fluke. Armand’s parents were music lovers who’d play everything from Bootsy Collins to Fleetwood Mac on the family record player. As an eight-year-old, Armand liked Chic and Kiss (“that’s a good way to define me really”), and was an impressionable 12 when pivotal electro cut ’Planet Rock’ came out. “That was it, I found my path, it was hip-hop and I stayed hip-hop for a really long time.”

When introduced to house music in the late ’80s, he didn’t like it. “I hated it at first, I was like, ‘The beat never changes’. So I went back to my hip-hop.” He soon did get into house, though, via tracks such as the Jungle Brothers’ ‘I’ll House You’ and other hip-house bridge records. “I realised it was urban music really, you know,” he says. “City music, and predominantly black folks, and I was like, ‘Wow, I really like this’, but had to experience it — my friend playing it for me wasn’t enough. This music is very much an experience. Listening to house music at home — even now — is cool, but it’s church music. It’s in a social setting, it’s in an environment with other people — and loud, you know. It’s very communal, so when I experienced it in that proper setting, I really liked it.”

Armand had been making beats at home from 13, but in the late ’80s started making his own house music — completely self-taught with no mentor, studiously reading manuals to figure everything out. He was pretty much the only person in his home city of Boston making house at the time, and when rave hit, he started DJing at local club The Loft — still playing house music.

One day, pals who were driving to New York suggested he accompany them and drop off some of his tracks to a few record labels. “So I went to three labels — Nu Groove, Nervous and Strictly Rhythm,” he recalls. He tells how Strictly co-founder Gladys Pizarro signed some of his music to Nervous, “and it literally changed my life. I was literally ecstatic.”

He used pseudonyms such as Deep Creed, Circle Children and Armand & The Banana Splits for his first few releases, before reverting to his real name for the siren-fuelled, ravey bleep-house cut, ‘Witch Doktor’. He soon became a club remixer du jour, and took influence from a Masters At Work remix of Debbie Gibson that took one breath from the original. When commissioned to remix a Tori Amos song, ‘Professional Widow’, he grabbed a bar from the bass-playing in the parts, souped it up and used it to propel the track.

A fan of breakbeat hardcore since his rave days at The Loft, Armand had tried making some drum & bass tracks of his own in the mid-’90s, but didn’t think they were good enough to release. “I also had it in my head that no Americans made drum & bass, and the ones that did, nobody in the UK paid attention to, you get what I’m saying?” he says. “It was locked off 100%, so why make drum & bass? It’s gonna go nowhere.”

Instead, he used d&b techniques in his house remixes of acts like CJ Bolland (’Sugar Is Sweeter’) and the Sneaker Pimps (Spin Spin Sugar’), and unwittingly coined a new important scene in the UK — speed garage. Was he aware of this at the time? “Not really, because I didn’t live in the UK,” he says. “I just made them because I liked drum & bass. Really, I’m a house guy. ‘Spin Spin Sugar’ was my closest attempt to drum & bass with a house tempo, you know what I mean? It was about the sounds.”

Speed Garage

Time-stretched vocals, bassline sensibilities and a stop-the-beats ‘drop’ were kinda new in house music, and when UK act Double 99 sampled ‘Armand’s Drum N Bass Mix’ of ’Sugar Is Sweeter’ for ‘RIP Groove’ (“I thought that record was amazing,” says Armand) and a raft of skippy garage tracks with junglist tendencies followed in its wake — fuel for assorted South London after-hours sessions — a new genre of electronic music coalesced.

But Armand had already moved on. He was recruited for a Heavyweight DJ Title bout versus UK champ Fatboy Slim at Brixton Academy, involving a full-size boxing ring, the gowns and gloves and announcer and everything. “It was like a real boxing match, you know what I mean?” recalls Armand. “It was cool.” Despite battling an ultimate DJ showman at the peak of his powers, Armand more than held his own blow for blow, with your DJ Mag hack actually pronouncing him the victor after witnessing the equivalent fight up north at Tall Trees Yarm just before the London leg.

These DJ spectacles significantly raised Armand’s profile in the UK, and he soon scored a No.1 — globally — with the filtered disco feel-good vibes of ‘You Don’t Know Me’. The worldwide success of the single caused him to significantly slow down his productivity, after a particularly frenetic 1990s — following an epiphany in Ibiza. “I was like, ‘I’m good, I’m tired, I’m gonna slow things down, and I’ve never worked as hard as from that day,” he tells DJ Mag.

He calls his next two albums “a piece of shit” (‘Killing Puritans’) and “not good” (‘Gandhi Khan’), until ‘Hear My Name’, which was his nod to the electroclash sound of the early noughties (“Yeah, I loved what Felix [Da Housecat] and DJ Hell were doing”), and the euphoric ‘My My My’ put him back in the arena. Audaciously, ‘My My My’ had 75 seconds of drop, including about 20 seconds of complete silence before it slides back in. Although now well into his self-confessed “lazy phase”, Armand started digging the noisenik electro sound of Justice, MSTRKRFT et al., and the so-called fidget house sound of Crookers. It was at this point — 2007 — that he was introduced to A-Trak via P-Thugg from electrofunkers Chromeo. The other member of Chromeo, Dave 1, also happens to be A-Trak’s brother.

Scratch DJ

A dozen years younger than Armand, A-Trak — aka Alain Macklovitch — was big into hip-hop as a kid and soon got into scratching and trying to emulate the skillz of various scratch DJs in his early teens. “I got into DJing at a time when turntablism was really exploding, so there were all these new tricks to learn,” A-Trak says. “I worked very hard, practising very methodically.”

He was befriended by a local Montréal DJ, Kid Koala, and looked up to crews like the Invisibl Scratch Picklz and The Executioners, “and that whole generation of battle DJs — Qbert, Mixmaster Mike, Roc Raida, Babu...” He reverentially lists a raft of DJ names. “That entire generation of incredible battle DJs all stopped battling at the same time — and I got into it the next year,” A-Trak continues. “All I wanted to do was follow in their footsteps, and humbly try to push it maybe a little further.”

At 15, A-Trak entered the DMC World DJ Championship — and promptly won the thing. “I don’t think it registered on a deeper level till later,” he admits. “I was happy when I was announced the winner, it was a very pure emotion. Were any of the older guys pissed off? Yeah, some of them were, but the DJs that I really looked up to embraced me, they welcomed me. I learned pretty quickly that you can be one of the greats, like Qbert or Jazzy Jeff, and still welcome the next generation with total generosity.”

He immersed himself in the battle scene and won other competitions too, and when he’d visit New York he’d hang with the late Roc Raida at his house. “That sort of gracious, open-armed welcome that I got from my heroes literally changed my life,” he says. “Seeing the people who were sort of haters, I just thought, ‘I never want to be that person’.”

Beyond the battle scene, he’d go to California, play shows with Peanut Butter Wolf and hang out with him there. “I got to witness how he was running Stones Throw Records — that influenced the do-it-yourself approach to a lot of my projects later in life,” he continues. “I’d go to New York and make the pilgrimage to Fat Beats, and got to meet some really dope underground rappers who worked there, and started collaborating with them. I went to the LA Fat Beats store and the Beat Junkies were working there. Through being world champion, I was able to meet a lot of people right away.”

In softly-spoken, eloquent terms, he reminisces about meeting Beastie Boys, Biz Markie and Beasties collaborator Money Mark, who showed him how to mess around with FX pedals, live looping and feedback delay. “That made me think differently about making music too,” he says. “Guys like Kid Koala and Money Mark opened my mind, so later on when I got into production, those seeds were already planted.”

When A-Trak gravitated towards club DJing, he had to figure out how to balance everything he’d learned. “I knew that, at a lot of clubs and venues, people could appreciate routines in small doses — but they wanted to dance,” he says. “So I had to learn how to rock a party set. I also had to figure out for myself how to toss in little tricks, how much to do it, and at what part of the night, how to use these tricks as parts of the mix as opposed to just a show-off section. It’s easy to just stop the music, turn on the spotlight and say, ‘Hey, I’m the best in the world at this, watch me!’, but it’s cooler to figure out how to make it serve the mix. That was years of experimenting.”

He hooked up with various DJ crews, started thinking about how to give his DJ skills a wider platform, and on a trip to London in 2004, he randomly met a certain Kanye West. Kanye was hanging incognito in the Deal Real record store off Carnaby Street with his friend, the singer John Legend, and the in-store session rapidly turned into a freestyle hip-hop jam when Mos Def walked in and the rappers started freestyling on the mic. A-Trak had performed a scratch routine incorporating Talib Kweli’s ‘Get By’ and a Kanye instrumental, and when he spoke to Kanye afterwards, the rapper — clearly impressed — invited A-Trak to be his tour DJ.

“He told me right away that what he liked was not only that I was really skilled, but he understood what I was doing,” says A-Trak. He starts remembering one of their early hangs, where Kanye said that he didn’t really understand what other scratch DJs were doing; he got lost, didn’t recognise the records they were using, and couldn’t relate. “‘But when you do it, you’re using records that people know and walking people through it. I get it more’. So we shared that goal of championing these amazing things about hip-hop that we care about, figuring out how to break through any barriers still left over from the past.”

“My generation of battle DJs had sorta hit a wall — after 2000, 2001, less people were going to battles,” A-Trak continues. “I was still young when that happened — 18 or 19 — and when I met Kanye at 22, I already knew that I wanted to figure out how to break those walls and continue pushing this type of DJing that I care about.” Over the next three years, they formed a successful creative partnership during which they picked up assorted things from each other. A-Trak talks about learning a lot from Kanye’s artistic vision, “how to take something very pure, culturally and musically, and present it to the masses in a way that’s not diluted, but that more people can understand. Kanye did that in the way he sampled soul records.” He scratched on Kanye’s ‘Gold Digger’ and influenced the ‘Graduation’ album, in an almost indefinable way, by playing Kanye the music he was working on separately, and simply hanging in the studio — being in the room.

Fool’s Gold

A couple of years into his time with Kanye, he started his own record label — Fool’s Gold. A-Trak was dating and making music with sassy Chicago rapper Kid Sister at the time, and wanted his own outlet. Over the ensuing 13 years, despite some “forks in the road or actual obstacles”, Fool’s Gold has built itself up into one of the most influential — and successful — independent labels in the US.

“I’ve learned so much from running Fool’s Gold,” A-Trak says. “Some people tell you that not every artist can have a label, because when you have a label, you have to be available to your artists — it’s no longer just about you. Certain artists tune out completely when they’re in their creative phase, and so when they have a label, it becomes tricky because you have to wear two different hats — they might not be reachable when they’re coming up with some crazy new idea. For whatever reason, in my artistry I never completely tune out. I might work on something for a couple of hours, then work on something else for a couple of hours. I’m always reachable — my brain is half creative and half entrepreneur.”

After a year of Fool’s Gold, he told Kanye that he had to stop working with him. “Sometimes we’d go overseas and rehearse for long hours, and I started realising that I needed to be available to the Fool’s Gold team,” he recalls. He talks proudly about how the label keeps him close to so many creative artists. “We sign a lot of new artists, we champion a lot of new artists at our Fool’s Gold Day Out festival events, and have become a breeding ground for the new generation of cool hip-hop. There’s a real energy from being around those people. It’s literally the fountain of youth for me, it energises me. It keeps me grounded, keeps me excited, I can never be jaded about anything.”

Meeting

The two Duck Sauce dudes first met each other in 2006, “in a car on the way to a party in Ibiza,” according to A-Trak. “We started hanging out in New York, and figured out straight away that we were gonna be best friends. We had similar taste in music, similar sense of humour... we were both sorta in the house scene, but hip-hop guys at heart.

“I didn’t realise then that Armand has a very blissful, minimalist, Zen approach to his career,” A-Trak continues. “He’s not like a typical DJ who grinds in the studio every day — he’s chilling all the time. He’s got life figured out, he’s the coolest guy on the planet. He hangs out every day, he sunbathes, and then once or twice a year he’ll go make a track and it’ll be the best song of the year. So when I met him, ‘Bonkers’ with Dizzee Rascal was the biggest song in the world.”

A-Trak and Armand quickly became good buddies, and would hang listening to records and go out to clubs together. “This was when the electro wave was happening — MSTRKRFT; all the Ed Banger stuff like SebastiAn, Uffie, Justice; Crookers, Simian Mobile Disco, Soulwax... Erol [Alkan] was championing that stuff in the UK,” says A-Trak. “That was a scene that I embraced, and I started making my first couple of remixes going for that sound. And I was friends with some of the French guys — as soon as DJ Mehdi and I met, we became best friends right away. As I went from hip-hop into electronic music, this was the side of it that I wanted to tinker with. I listened to Switch and Sinden and fell in love with their swing and drum programming, and the way they would cut up rap vocals just felt more familiar to me.

“Armand was aware that this whole new thing was happening, and he loved it,” A-Trak continues. “A lot of the house heads from his generation were resistant to that change.”

It wasn’t until after two years or more of friendship that the idea of collaborating came up. “And I don’t do collabs, by the way,” says Armand, stating that the only collabs he’d done up to that point were with DJ Sneak and Junior Sanchez. “Why not? I don’t necessarily need another chef in the kitchen, you know what I’m saying? I just wasn’t used to it, but I was up for it. I didn’t know if I was going to be able to find a partner groove, but once we started to do it, I was like, ‘Oh, I get this now’. You know, you backseat some stuff and you’re adamant about some stuff, it’s kind of like how it works — both of us give and take.”

The first track they recorded together was ‘aNYway’, sampling long-lost NYC act Final Edition’s 1979 discofunk B side ‘I Can Do It (Anyway You Want)’. The rest of their initial burst is pretty well, err, duckumented. The Grammy-nominated ‘Barbra Streisand’ dropped in 2010, topping charts right across the world, and then came the wolf-sampling ‘Big Bad Wolf’, ‘Radio Stereo’ — a reworking of 1982 track ‘Radio’ by UK new wave act The Members — and ’NRG’, which sampled Melissa Manchester’s 1985 poppy non-hit, ‘Energy’. These were all rounded up on 2014’s ‘Quack’ album, complete with wacky skits in-between tracks, and were punctuated by some big EDM shows.

After Duck Sauce’s initial success, Armand was introduced to a side of electronic music that he didn’t know much about. “A-Trak showed me the world that I did not know existed, the festival circuit at that time, you know? Travelling with the likes of Justice and MSTRKRFT and Skrillex and David Guetta and doing these huge festivals. DJs putting on these massive shows was all new to me. I was a babe in the woods in that scene.”

He talks about playing massive EDM events on big stages with pyrotechnics and dancers, a sign of how times have changed from the small, sweaty 150-person clubs he was used to playing. “It’s still the same idea, it’s still based in house music, you know? It’s still based in the same concept. I know other people probably want to hate on all of that stuff, but I don’t. I just never thought I would be immersed in this. I get it, it’s big business, for sure, but really, when you’re there and you’re doing it, you see how much fun the people are having, you know what I’m saying?”

When touring, Armand revelled in the fact that most people in the EDM scene didn’t really know who he was or where he came from. “I was just like the second guy in Duck Sauce, y’know? They didn't know anything about speed garage or whatever, it’s not important and I didn’t care to even tell them. I loved it. I mean, it’s a great position to be in, you know? I was honoured. I didn’t need to tell people where I’d been, I didn’t need to demand that you respect me because I made ‘Witch Doktor’, you know what I’m saying? It’s not my personality anyway, but it’s definitely a position I never thought I’d be in.”

Armand was out of his comfort zone, but immediately felt at home in the EDM world. “The coolest thing about it all is that I realised that the rave scenes from my days, and the house music thing, it really is just the same energy, you know?” he says. “The energy hasn’t changed.”

Reunited

After making a big splash, the guys went their separate ways until about a year ago, when Armand called A-Trak up. “I just said, ‘Are you ready to wind up the duck again?’” Armand recalls. “It’s kind of what it is. I think we wound it up and you know, it did its march and then it stopped, and then that was that. I said, ‘It’s time to wind it back up again’.”

And here we are. The guys have a bunch of new tracks ready to drop, some big shows in the pipeline, and the two great friends are evidently enjoying themselves with their fun-time house music more than ever.

“House music will always win, it’s the genre that won’t die,” says Armand. “You can make house music till you can’t make it any more. It seems like as long as you make a club track that somewhat gets people boogieing, you can still be relevant. There’s no other form of music like that. Not one.”

After lots of laughs and wise-quacks, the Duck Tour completes its round trip and docks back at its duck stop just off South Beach’s Lincoln Avenue. The interview has gone swimmingly — like water off a duck’s back. DJ Mag has one last piercing question for the pair. How was the Duck Tour for Duck Sauce? “Ducktastic!” says Armand. “The best part was going in the water. When we’re in the water, we don’t have to waddle.”