Forget another summer of love — this is the summer of crisis for UK raving

With music venues shuttered across the nation, and no timeframe for reopening, the future looks bleak for UK clubbing. DJ Mag speaks to venue owners, promoters and ravers about their hopes and fears regarding government funding, illegal raves and the grassroots scene

Being in close proximity with people you don’t live with is a dangerous activity. Being in a confined space is a dangerous activity. Dancing close to other people is a dangerous activity. Therefore, right now, a large part of electronic music culture is classed by Public Health England as dangerous.

On Sunday 5th July, the government announced a £1.57 billion support package to help the UK’s arts, culture and heritage industries — including music venues, independent cinemas, museums, galleries, theatres, etc. — “weather the impact of coronavirus”. Despite this undoubtedly being a step in the right direction, it still left a lot of unanswered questions.

It still isn't clear, for example, how much would go to support grassroots music venues — unlike the £2.2 million package announced specifically for them by the Scottish Government in July. And if £1.57 billion can sustain the sector throughout the rest of the pandemic. When you consider that West End theatre productions are used to generating £760 million in ticket sales alone each year, and France have pledged €7 billion to protect the arts in their country, industry figures are left wondering if this will be enough.

Only a tiny minority of businesses in this sector have communicative disease insurance cover, meaning that we’re facing the reality of hundreds of venues disappearing. Even worse than that, there’s no indication when social distancing will end and they can make money again. Even with support, hundreds of thousands of jobs are still at risk. Something that would be catastrophic for what was described as one of the UK’s biggest social, cultural, and economic successes of the past decade in an open letter to the Secretary of State, Priti Patel, by the Music Venues Trust (MVT) — a charity that work to protect grassroots music venues.

Mark Davyd, MVT founder and CEO, is facing the most challenging week of his career when he first speaks to DJ Mag in mid-July. “We’ve got 93% of the sector at some risk of being closed down, with only 7% that are fully safe, and that’s because they own their own buildings,” he says. “How much risk is greatly dependent on the philanthropy of their landlords.”

Rent has become a huge burden on independent venues now because (save from selling merch and collecting donations) they have no income at all. “How many are going to close will be largely down to the landlords. It’s not any way to run a huge sector like ours,” Davyd says.

The week before the government announced the support package, the MVT wrote their open letter to the government outlining exactly what they need to have a fighting chance of not losing the sector completely — a £50 million financial support package available immediately, and a reduction on VAT for future ticket sales.

If we lose these venues, it will have ripple effects for decades. “I call this the kebab effect, because it’s easier to understand,” Davyd explains. “I’ve eaten a lot of kebabs, but I’ve never left my house at 11:30pm to go and get a kebab — I always do that because I’m out in the night-time economy. This sector supports hundreds if not thousands of businesses [pubs, bars, restaurants, transport, takeaways, agents, programmers, riggers, and so on] based around them.”

Grassroots music venues produce all the talent — talent that generates £5.2 billion for the Chancellor of the Exchequer every year. Knocking out the first rung on the ladder means there’s no route into the industry. “We’re only asking for the amount [£50m] that any one of our major stars pays in tax per year. We need it very, very fast now, because businesses are going to start closing in the next few days, frankly.” DJ Mag catches up with Davyd again the day after the government’s announcement and he is optimistic. “We’re very happy with the way that the discussions have gone with the government,” he says, adding that he is in a good mood. “We are happy based on the Prime Minister’s statement and the Chancellor’s statement, both of which reference music venues, that the intention is that we will get the support we’ve been asking for.

“There are some complications — the devil is always in the detail — but I think we are starting from the position that it’s clear what the fund is intending to do, and we are hoping to work with the DCMS (Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport), Arts Council and the government to make sure we achieve that. We’re pretty confident that it’s achievable and there is the funding to do that. This is quite a dramatic change to the way that music venues have been treated in the past.”

Later in July, leading figures from the electronic music industry launched the #LetUsDance campaign, issuing an urgent plea for direct support from the UK Government for the dance music sector. Just a week after the campaign began, Whitehall confirmed that electronic music would be recognised within the arts, announcing a £500m Culture Recovery Fund for the sector.

Michael Kill, CEO of Night Time Industries Association (NTIA), welcomed the move. “We are extremely pleased that the Government and DCMS have released the guidance and eligibility criteria for the Cultural Recovery Fund and have included Electronic Music and many other subgenres," , he said in a statement following the news.

“This is a positive step forward, but we must maintain pressure on government to gain clarity on the roadmap for businesses that are still unable to open, and fight for further support."

When you speak to people on the underground circuit, though, the uncertainty is palpable as many questions remain unanswered, and the return of live music performances was delayed by UK Government. “As promoters, our job relies entirely on gathering people together, and with organised mass gatherings currently off the cards we are facing a very uncertain future,” Aidan Doherty, founder and resident of London-based party Warm Up, tells us. “Promoters have suffered a complete wipe out of income.

“I’m really concerned that a lot of the smaller venues that we use and love won’t make it out the other side,” he says. “It’s going to be interesting to see how the whole scene can pull together. At the moment some artist fees, agent fees, the rider requests, and all that are just astonishing. Maybe this is the chance we all need to look at how imbalanced some of these relationships have become.”

Stuart Forsyth, promotions and events manager at MiNT Warehouse, has also found himself wondering how the scene as a whole will respond to this crisis. The Leeds-based institution has renovated their main room during this time, but they don’t know how long it will remain empty. “I’ve been happily surprised and at the same time disappointed by some of the agents and artists throughout lockdown,” he says.

“We’ve had some huge DJs who have come to us offering to play gigs for rock bottom prices to help us get back on our feet, and Darius Syrossian offering to play his rescheduled gig for free. But then others that we’ve given tens of thousands of pounds and private jets to over the years are still expecting to get full whack. It’s a shame, but I feel like a lot of these artists and agents have made so much money they have become totally out of touch with reality.

“It’s no secret DJ fees have been spiralling out of control the last five years, it’s hard to make any profit these days, it’s depressing that for so many of them it’s all about money. There will be many artists you won’t see at MiNT in the future as they don’t care about us making a fair share of the profit. The industry needs resetting, otherwise there will be no future for clubs like us.”

Over at The Cause in Tottenham, Stuart Glen and his team have procured an additional 5,000-square-foot room in a warehouse space attached to the club. Called The Theatre, it was crowdfunded by giving people the option to buy a ticket to, or a round of drinks at, the future launch night. The rapid development of the area surrounding the club has been slowed down, so despite fending off multiple near closures it’s looking like they might have a couple more years left in their current location.

“Obviously everyone is shitting themselves, and I am as well,” he tells us over the phone. He can only speculate as to what measures will have to be in place whenever they can get back to business as usual. “I think it might involve getting a test somewhere nearby, or on premises. Then test and trace [taking everyone’s details on entry and keeping them for 30 days in case of an outbreak], the deep cleaning of venues, and temperature checks.”

Broadwick Venues operate a huge property portfolio which includes London venues Printworks and The Drumsheds, along with the likes of Depot Mayfield in Manchester. Their business model involves facilitating 5-10,000 people converging to dance — a risky operation following a pandemic.

“It’s been a nightmare basically,” Simeon Aldred, one of the directors of Broadwick Venues, tells DJ Mag. “Right at the start of this we heard other promoters saying, ‘It’ll be okay, we’ll still be able to do this show in July or August’. But over the next two-week period it became very clear that this would be a six or nine, or 12 or 24-month problem.

“Every show had sold out, so we’re taking 20 sell-out shows and trying to decide what we’ll do with them,” Aldred continues. “We went from disbelief, and dealing with the emotional issues of it all, to knowing what was real. Now we have a number of plans and scenarios we’re working to.”

They seem more confident than the independent promoters you speak to. But with a number of “venue models” — from owning freeholds to long leases to joint business ventures with the owners of the properties they use — they have more breathing space.

A lot of small venues will not survive even with the state intervention. However, it is likely that small venues will open before big ones, and festivals and big-name bookings could be financially unobtainable. This means that community-driven clubbing and DIY parties will flourish, leaving more room for fresh talent to step in and shake things up. This could act as a hard reset of the scene; a shift of values moving away from the superstar DJ, the VIP areas, the guestlist culture, the orgy of Instagram curation in a sanitised, homogeneous corporate clubbing environment — the aspects of the clubbing ecosystem revolving around money and status rather than community or musical innovation.

You can see this happening already: DIY parties and small-scale unlicensed events have been steadily rising since 2017, but now they’re popping off all over the country in woods, fields, under motorway bridges — anywhere.

The council in Nottingham sanctioned a 40-cap ‘socially distanced rave’ in a wooded area at the beginning of June. Put on to draw attention to issues faced by promoters now, the crew, called Nitty, did a good job getting a lot of media attention. But since then there’s been talk of so-called ‘drive-through raves’, and socially-distanced events with people sat on chairs on the dancefloor. These are gimmicky and largely irrelevant as a long-term solution, as socially distanced events are a gross contradiction of the values that the whole sociological phenomenon of raving is underpinned by. So, it’s no wonder that this was swiftly replaced with a sharp uptick in DIY, unlicensed affairs.

It’s no secret that unlicensed partying has exploded. Of course, the large majority of these parties receive no exposure in the mainstream press, because they are organised by experienced people. But others, advertised on Instagram, Snapchat and WhatsApp, by a less experienced contingent of promoters, have seen some trouble — notably at two raves in Manchester which reportedly saw three people stabbed, one 20-year-old die from a suspected drug overdose, and an investigation into the rape of an 18-year-old woman.

We spoke to someone that attended one of the Manchester parties which, according to the Greater Manchester Police, were put on by gangs rather than an established free party crew. “When I was in the taxi on the way to one of the parties, my mate that was at another rave in Salford, text me to say, ‘There’s been a stabbing, I’m getting off. I’ve just seen a body on the floor and it’s ‘anging’,” said the source, who asked to remain anonymous.

“When we got to a different rave in Droylesdon — it took us ages to get there, walking down a massive bridge and a hill — there was a sea of people, about 2,000. There were big, juiced-up guys wearing skin-tight t-shirts trying to tax [charge] people a tenner to get in.”

They left after half an hour due to the sketchy atmosphere. The following week, the Greater Manchester Police announced they’d be cracking down on the events and later arrested two people. But with the police facing their worst ever annual budget cuts, following a crippling decade of Tory-led austerity, it’s unlikely they’ll have the resources.

An organiser of a long-standing illegal rave in London is watching from the sidelines. “A lot of people feel uncomfortable going out to a rave during this lockdown, maybe they live with a vulnerable person, or feel it’s not morally right to get out partying just yet,” he tells us, anonymously. “I respect that. Other people are obviously hungry to let their hair down and re-connect with like-minded individuals, they feel safe to be around others, and again I fully respect that.” His crew have decided not to put events on for now.

“The raves in Manchester clearly weren’t responsibly run, and whoever organised those went too far, too soon,” he continues. “It’s a real shame because there was a complete lack of respect for the UK’s incredible underground rave history and the current scene. There are plenty of crews who run things very smoothly and safely, and to be honest, you’ll never hear about those in the press for that exact reason.”

“There’s evidence a rift has opened up,” Fiona Measham, founder of The Loop and long-standing researcher into clubbing culture recently told the Guardian. “Some older ravers, DJs, and promoters are advising people to respect social distancing and not attend illegal raves, but, with echoes of the early 1990s rave scene, some younger people think they should have the right to party and the government is trying to curtail their freedoms.”

This split in norms and values between clubbing tribes became more pronounced two months into lockdown, when people started getting itchy feet. Pete, a 20-year-old student living in London isn’t concerned about the pandemic in the slightest. He went to an illegal rave a month into lockdown, we asked him about the atmosphere. “People were excited to party because they’d been locked up, you know?” he says.

Vinny, a 29-year-old music producer, usually goes out at every opportunity he gets. But not for now, he’s too anxious. “It could put some people at risk; it’s still transmittable,” he says. While Charlie, a 31-year-old American expat, also attended an illegal rave in London a few weeks ago. “There was a forbidden fruit aspect,” he recalls. “The energy was like when someone gets out of jail.”

Warm Up promoter Aidan Doherty also touches on this during our interview. “I’ve noticed, sadly, how divided the scene has become in some respects,” he says. “There’s an almost 50/50 split of people who want to get back to living and doing what they love, and the other half who feel that it’s way too early to even consider this.” He adds, “People are more emotional than ever right now, which is resulting in cases of public disorder, and more and more rebellious behaviour.”

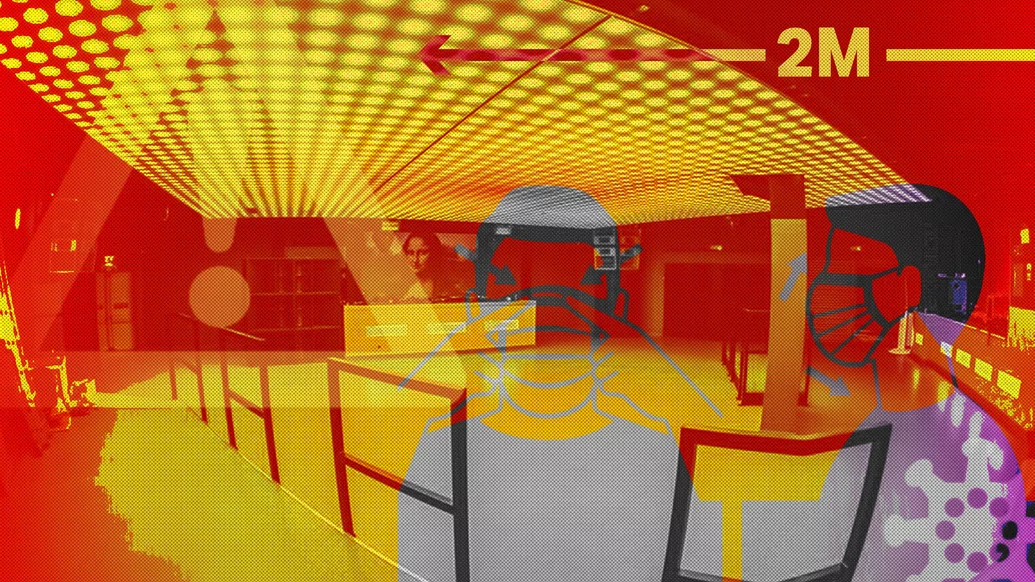

Our scene has reached a critical point. The government has acted, but damage and loss to people, their livelihoods, and the wider culture could still be catastrophic. There could be some shifts of norms and values that could benefit our scene, but that’s only going to happen if there’s anything left. London club Hangar18 shared their capacity planning based on government guidelines in June. The diagram showed their capacity dropped from 370 to 26, an impact the club described as “a nail in the coffin for us”. Even now the government guidelines have changed, moving the two-metre rule down to one metre+, and allowing socially distant outdoor music events to take place, we’re still some distance off clubs being able to safely, and viably, open.

At the moment, we are becoming increasingly divided, which is the polar opposite of what our culture is all about. There are going to be hundreds of illegal parties this summer, but the talk of another ‘summer of love’ is bullshit — this is the summer of crisis. “The ethos of the club scene that we helped to create was not about dividing people: it was about uniting people,” Danny Rampling told me during an interview in 2018. Those words should be ringing in everyone’s ears as we navigate one of the biggest challenges to that vision in the past 30 years.

#SaveOurScene