The future of gaming in electronic music

The worlds of computer gaming and electronic music are merging like never before, with virtual raves, AI-generated musicians and concerts inside massive multiplayers like Fortnite becoming commonplace. DJ Mag investigates what this could mean for the future of clubbing and dance music

What if the next electronic music concert you went to was just... a game? Imagine for a moment: the concert would happen virtually on a cloud server, and instead of purchasing a ticket upfront, you would simply log into a website via your laptop or mobile phone to gain access to the concert for free. Upon logging in and choosing your avatar and username, you would suddenly be thrust into a fantastical, forest-like, computer-generated world, with a large virtual stage resembling a mountain sitting in the centre of your screen. The performer on the stage would resemble a DJ, but would actually be represented by a colourful, animated avatar.

There would be no way of telling whether there was even a real human behind the avatar, or if the image was just automatically computer-generated. But that wouldn’t necessarily matter because unlike at a bricks-and-mortar show, you could interact directly with the artist-character onstage, as well as with the millions of other fellow concert attendees watching with you, via a live chat forum on the side of the screen.

Every so often, the DJ would also launch collaborative mini-games that attendees would have to complete together in order for the show to go on — occasionally in exchange for rewards such as free, limited-edition merch or skins for your avatar. And of course, as the cherry on top, the music would sound great, and keep you dancing in your seat from the comfort of your bedroom for hours.

This might sound bizarre at best, dystopian at worst — but it’s already happened many times over, with some of the biggest artists and games in the world, as we explored earlier this year. In fact, the above is exactly what went down when Marshmello played two DJ sets for over 10 million viewers in Fortnite, when Minecraft staged not one but two electronic music festivals inside its game engine, and when Lindsey Stirling, donning a $40,000 motion-capture suit, performed as an avatar inside an interactive, virtual concert for over 400,000 attendees.

At their core, these electronic music concerts were all just games, marking a transformation in online music culture — and fans absolutely loved them.

COMPETITION

In its earnings report for the fourth quarter of 2018, Netflix declared that it “competes with (and loses to) Fortnite more than HBO”. The perhaps unexpected comparison between a video-streaming platform and a multiplayer game underscores how, in an always-on, oversaturated world governed by social media and advertising platforms, companies from seemingly disparate industries are really competing for the same two currencies: consumer attention, and cultural influence.

Musicians are certainly looped into this enormous pressure to put out a constant stream of content, instead of concentrating their energy around one album per year, as was the norm in the heyday of physical formats like vinyl records and CDs. One tactic that has helped some artists rise above the noise is tying their discography to another kind of narrative entertainment format, such as film or literature.

As Simon Reynolds recently wrote for Pitchfork, tying a project to a wider, non-musical narrative is “a way for artists to compete in an attention economy that is over-supplied while reflecting their enthusiasm for a vast array of ideas”. Hence why we’re seeing a sudden spike in musical biopics and documentaries, music-themed podcasts, and music-driven partnerships with games.

There’s a financial incentive for music companies to partner with gaming companies in particular as well. According to Newzoo, the digital gaming market generated $125.3bn in revenue in 2018 — already over $40bn more than what investment analysts project the recorded-music industry will make in 10 years’ time.

The relationship between the music and gaming industries has traditionally taken the form of record labels licensing catalogue on behalf of artists to be included in gaming soundtracks. Some of the most interesting examples of these licensing deals include Grand Theft Auto creating bespoke, in-game radio stations for select artists and labels; NBA 2K20 opting for a regularly-updated playlist as its soundtrack, instead of a static collection; and Rocket League working with indie electronic label Monstercat on exclusive compilations. But in all of these situations, labels are negotiating deals on behalf of artists. There is little to no direct engagement between artists and fans within the game itself, and the game developers ultimately own the user experience.

A major tipping point has emerged over the past few years, however, with the rise of esports. Looking to become pop-culture influencers in the mainstream, major esports tournaments are clamouring for musical talent to perform at their events — from Zedd at the Overwatch League finals, to TheFatRat at ESL One Hamburg. Top booking agencies now maintain internal master lists of artists who either are gamers themselves, or are interested in striking gaming partnerships in the future. And new major-label subsidiaries like Universal Music Group’s Enter Records and Sony Music’s Lost Rings are looking to bypass licensing deals and cultivate relationships with the gaming community directly, by signing artists who either love to game or make music that gamers love (read: lots of hard-hitting electronic and hip-hop music).

GAMIFICATION

The next decade will see another layer of a major transformation in the relationship between music and gaming — namely, applying game mechanics, commonly referred to as “gamification” to the way music is created, consumed and contextualised.

What exactly does it mean for something to be “gamified”? Industry experts point to numerous elements that distinguish games, especially multiplayer ones, from other forms of entertainment — including role-playing, coordinated action with other players, competitive scoring, and social features such as live text and video chat. This is a fundamentally different kind of fan engagement from what artists are used to encountering on streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music.

While these services do share some surface-level characteristics with popular games — tens of millions of active users, expansive geographic reach, multi-device functionality, multimedia features, etc. — the act of streaming music is actually quite an isolated, individualised and utilitarian experience from the listener’s perspective, with few social elements like live chat or comments enabled on the dominant platforms. Both artists and fans looking for a deeper connection are forced to cultivate it elsewhere.

In contrast, gaming-oriented livestreaming platforms like Twitch make fan interactions as direct, unfiltered and interactive as you can get online. “Twitch is so, so personal,” says CRAY, an electronic artist and gaming livestreamer, who streamed herself playing games for four to eight hours a day on average before embarking on her recent tour.

“I’m not being put on this pedestal of being ‘too famous’ or unreachable. You can ask me questions about how I made a song, or why I chose a certain lyric, or a certain game. I’m just on my computer in my bedroom, and so are you. I think that’s why my earlier gaming fans, who are now also my music fans, are some of the most dedicated ones I’ve ever had.”

Unsurprisingly, electronic music at large is at the forefront of hybrid music-game experiences, in part because the genre’s tools and sounds are almost completely computerised by definition. This lends the genre naturally to more experimentation, with new modes of music creation and distribution — especially those that incorporate machine learning to make tracks more responsive to user actions and storylines within a given game.

Adaptive music-making is an area of growing interest for some of the world’s top tech researchers. “Can we meaningfully allow for a given piece of music to morph and evolve with different impact on each hearing? Can this mutability engage artists’ imaginations in new ways?” Tod Machover and Charles Holbrow, of the MIT Media Lab’s Opera Of The Future group, proposed in an op-ed for NPR Music. “Can listeners — or even the entire environment — play important collaborative roles in building such a ‘living music’ culture?”

VIRTUAL BEINGS

London-based electronic artist Ash Koosha had exactly this kind of interactive and adaptive music experience in mind when he founded Auxuman — a self-described “new breed [of] virtual creative beings” named Yona, Mony, Gemini, Hexe and Zoya, who jointly released a debut album in September this year.

While Auxuman is not a game per se, Koosha says he was inspired directly by the concept of “non-player characters” (NPCs) — i.e. video-game characters that are controlled by the game’s artificial intelligence, rather than by human players themselves — in designing Auxuman’s five members and imagining fans’ future interactions with them. “In a nutshell, we’re giving NPCs talent, in a way that is fully digital and not controlled by humans,” says Koosha.

The team behind Auxuman — which consists of three full-time staff including Koosha, plus a network of freelancers — leveraged a technique known as neural voice cloning, which uses a set of deep-learning algorithms known as a neural network to synthesise a human’s voice based on pre-existing audio samples, to generate each member’s singing voice. Natural language processing techniques also helped generate song lyrics, based on each member’s personality. “Each character has its own ‘personality file’ that’s distinct in terms of identity, behaviour and psychological patterns,” says Koosha. “For instance, we imagine that Yona would prefer to read a certain type of poetry or magazine article, and those kinds of materials then become the dataset behind her personality.”

Auxuman is currently looking to integrate its members officially with games like Fortnite and Grand Theft Auto as NPCs and “resident artists”, and is currently in partnership talks with Twitch. In fact, Koosha envisions a future in which Auxuman’s members perform their “concerts” in a game world that is constantly evolving, based on new data inputs and user feedback.

“We haven’t fully achieved this yet, but we’re aiming to have the entertainers live on a game server that can be streamed onto a projector in a concert venue,” says Koosha. “The colour palette, stage design and overall narrative of the performances would all update in real time. As soon as we build server clusters, we can enable one-on-one interactions as well, whereby each user will be able to choose a different ‘narrative’ around the performer and the show based on whatever they want.”

Several artists and start-ups have already applied machine learning and artificial intelligence to the musical creative process — from Holly Herndon making a vocal clone of herself in her latest album ‘PROTO’, to start-ups like Boomy, Popgun, and Amper making music composition as easy for the everyday consumer as just clicking a button. What could make Auxuman even more ground-breaking, though, is if that same generative creativity is also applied to the way these musicians look and behave on screen as embodied avatars, and the way their narratives are being told to fans.

INTERACTIVE SHOWS

Wave, a virtual concert platform based in Austin, Texas, has already been staging these kinds of remote, interactive shows for years — except working not with artificial characters, but with real-life human musicians.

Formerly known as TheWaveVR, Wave’s first product was a platform for social, user-generated raves based in virtual reality — users could host and DJ their own parties in VR, with the option to design their own visuals using 3D design tools like Google Poly. Users could even take virtual “drugs” with each other, whereby the user experience would suddenly look extremely psychedelic, displaying trippy visuals that Wave commissioned a wide network of visual artists and designers to create for the app. TOKiMONSTA, Imogen Heap and Jean-Michel Jarre were among Wave’s notable early collaborators on exclusive virtual concerts and immersive album experiences.

But as with most other VR content initiatives, Wave found that the medium of VR was limiting in terms of consumer reach and revenue — so the company quickly began scoping out opportunities in other virtual environments, and is currently exploring concert partnerships with Twitch.

The intersection of music and interactive game design was a natural area of interest for Wave’s co-founder/ CEO Adam Arrigo, who previously worked at video-game company Harmonix as a designer and product manager for the likes of Rock Band, Fantasia: Music Evolved and Harmonix Music VR. Recent Wave shows have included not only loose, evocative “plots” — consisting of 10 different “scenes” created with the same open design tools that the company made available to its users — but also interactive, game-type elements that are otherwise difficult to impossible to implement smoothly in a bricks-and-mortar concert setting.

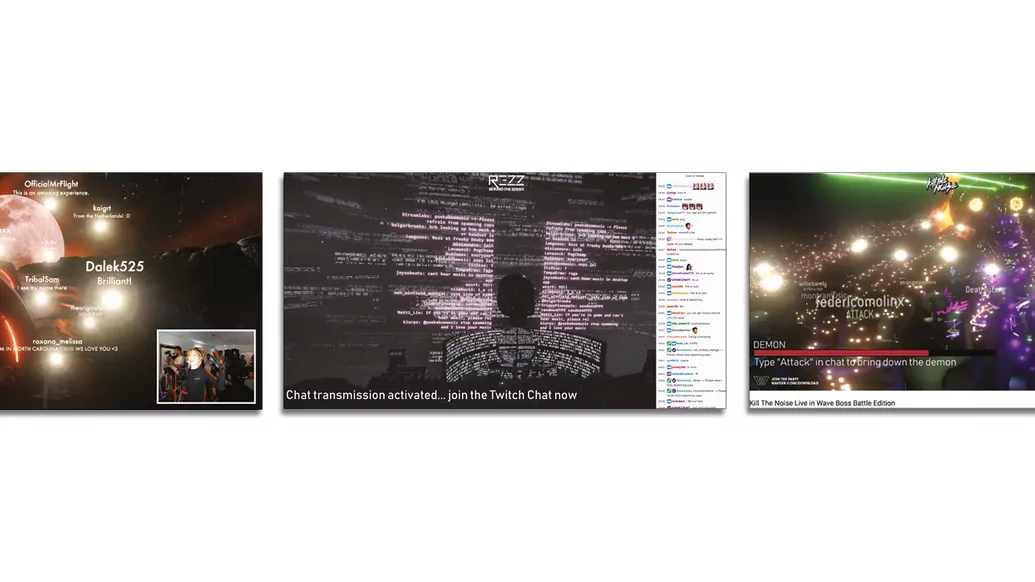

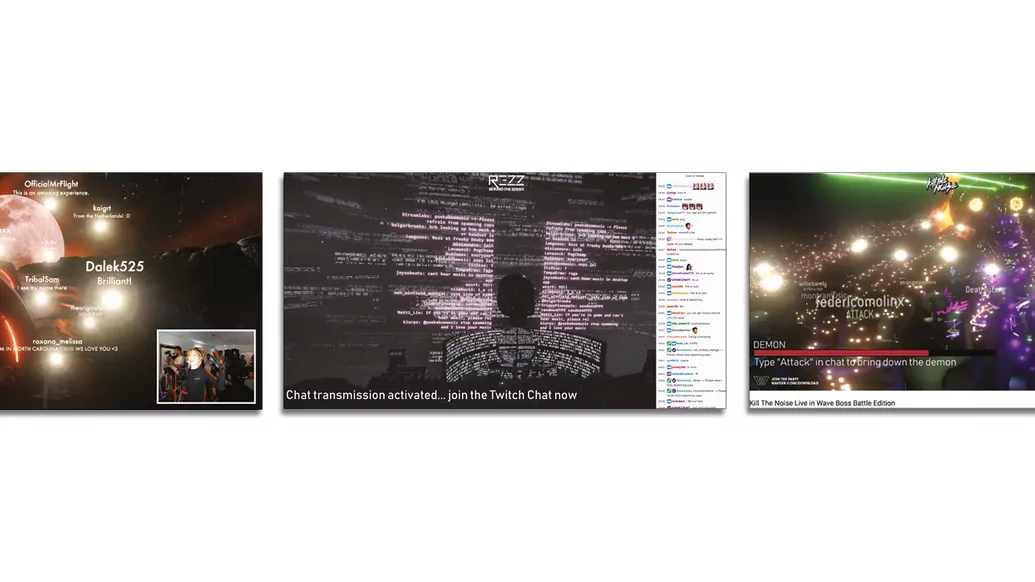

During a virtual concert that he gave in Wave, dubstep artist Kill The Noise staged a gaming-style “boss battle”, whereby attendees were invited to type “attack” in the live Twitch chat to help kill a demon that began shooting lasers from its eyes in the background. In another Wave concert featuring electronic artist Rezz, viewers could see their live chat comments broadcasted on a custom “Chat Transmission” visual that was projected and updated in real time on Rezz’s stage. And during Lindsey Stirling’s Wave show, viewers who posted in the chat bar would show up as stars in the sky in the cosmic virtual world on display.

The business models for these virtual concerts will likely resemble that of a growing number of video games, in that they will be “free to play”. You don’t have to pay anything upfront to play Fortnite or PUBG, but there are a myriad of opportunities to pay for additional skins, weapons, effects or other items once you’re further into the gameplay experience.

Arrigo envisions that virtual concert monetisation will work much the same way, especially if they live primarily within existing game environments. “I want everyone to be able to go for free, but then we could upsell them on virtual goods and interactions,” he says. “You could pay $100 or something to get your username displayed onstage for a few seconds. Or I think something like a virtual Chance The Rapper hat would sell really well at a virtual concert.”

In a separate article, Arrigo told this writer that he was interested in turning Wave into “the Live Nation or AEG of the virtual world”, consisting of “a network of digital venues across... interactive streaming apps, AAA video games — places where audiences are already socialising virtually”. A key difference from the actual Live Nation, however, is that production costs for virtual concerts would be much lower — saving money for both artists and fans.

In fact, Wave’s shows are already a much leaner operation than their competitors. Marshmello’s Fortnite concert reportedly took six months and around 30 to 40 people to develop; in contrast, Lindsey Stirling’s Wave show — which delivered a similar experience of Stirling performing to a virtual crowd as an avatar — took three staff members just three weeks to build. “Lindsey [Stirling] fills 5,000-cap venues, and it would cost $100,000 to put on that physical show,” says Arrigo. “But we’re just three 25-year-olds, and managed to reach 400,000 people virtually. The economics of virtual shows just have drastically better margins.”

Keeping concert economics lean will be a growing imperative in the future, especially as the number of creators in music and visual art continues to increase and as more event properties face the consequences of climate change and other environmental shifts. “It’s being discussed heavily in Europe right now: how can we keep the live music economy sustainable in 10 years’ time?” asks Koosha. “One possible solution is to divide it partially between concerts that do and do not have the artists actually present.”

THE REAL THING?

With virtual concerts, a natural concern also comes up of whether virtual experiences between artists and fans can ever be as “authentic” as the real thing. But the question begins to sound unnecessary — silly, even — once you position these concerts within wider trends in pop culture.

In fact, it’s becoming increasingly normalised for humans to engage with digital representations of each other, instead of their actual selves. In-game concerts are emerging at the same time that virtual influencers like Lil Miquela are gracing billboards in Times Square, Bitmoji-type avatars for the likes of Jennifer Lopez and A$AP Rocky are getting their own agents for brand partnership deals, and hologram tours for deceased celebrities like Whitney Houston and Roy Orbison are taking the world by storm.

“It’s weird how people use the term ‘authenticity’ as counter to avatar culture, when we’re all already avatars on social media,” says Arrigo. “I have friends who spend their day meticulously crafting their Instagram and posting black-and-white photos of themselves smoking cigars in LA. I’m thinking, that’s not actually you.”

The growing influence of artificial intelligence on pop culture also brings up fears of automation replacing music creators’ careers. Over two years ago, the music industry was freaking out about the possibility of “fake artists” populating mood- and activity-driven playlists on Spotify — stealing potentially valuable promotional real estate (and royalties) away from human artists who shed blood, sweat and tears to cultivate a sustainable music career.

In a world of gamified music culture, a similar fear could very easily emerge around “fake performers”. Isn’t that what Auxuman is at the end of the day: a set of avatars who can’t be traced back to individual human personalities, and who thus are “fake”?

Koosha pushes back on this claim, in part because Auxuman could not have come to life without a team of human developers and artists behind the group. “We respect them as equally as human beings, because they’re built atop data from human life online,” says Koosha. “Someone, somewhere out there, wrote the material for the model that trained Yona’s lyrics. Even though the current iterations are a bit wonky, we believe there’s a certain level of life behind them.”

Record labels and other music companies are far from obsolete in a gaming-centric environment, but must adapt quickly to meet the demands of the format. That means thinking like movie studios and gaming companies, and hiring visual designers and software developers, not just concert promoters or digital marketers.

“Once you reduce and automate more labour, you need even better curation, and that comes from humans with taste and critical thinking,” says Koosha. “There’s a large community of human curators and producers who don’t necessarily want to perform or have a public image, and who will be massive forces behind these virtual entertainers.”

This mindset signals a revolutionary new model of artist development and concert production, whereby interactive game mechanics are just as important as actual music production or stage presence — requiring a whole new set of skills and behaviours to navigate successfully. And while games are powerful means to unlock deeper social connections among artists and fans, the wider gaming community has also proven in the past to be a ruthless corrective force against those who are not fully committed to, interested in or respectful of the culture — an important tip for musicians looking to dip their toes in the field.

“I tell all my musician friends who are interested in getting on Twitch that it’s not something where you can just jump on and off casually,” says CRAY. “That’s what Instagram Live is for. Twitch is a much deeper culture, full of its own words, behaviours, and emotes, that you have to take the time to understand and watch just as a fan. To any musician who tells me, ‘I want to do what you do’, I tell them they have to be ready to buckle down for life.”