The government's response to COVID-19 could kill live music as we know it

COVID-19 has rapidly impacted the music industry — leaving thousands out of work. The government dumbfounded many when it was suggested that those from an industry that contributed £5.2bn to the economy in 2018 retrain and find different jobs. Here, Wil Crisp asks: is the government's response to the pandemic causing permanent damage to the music industry?

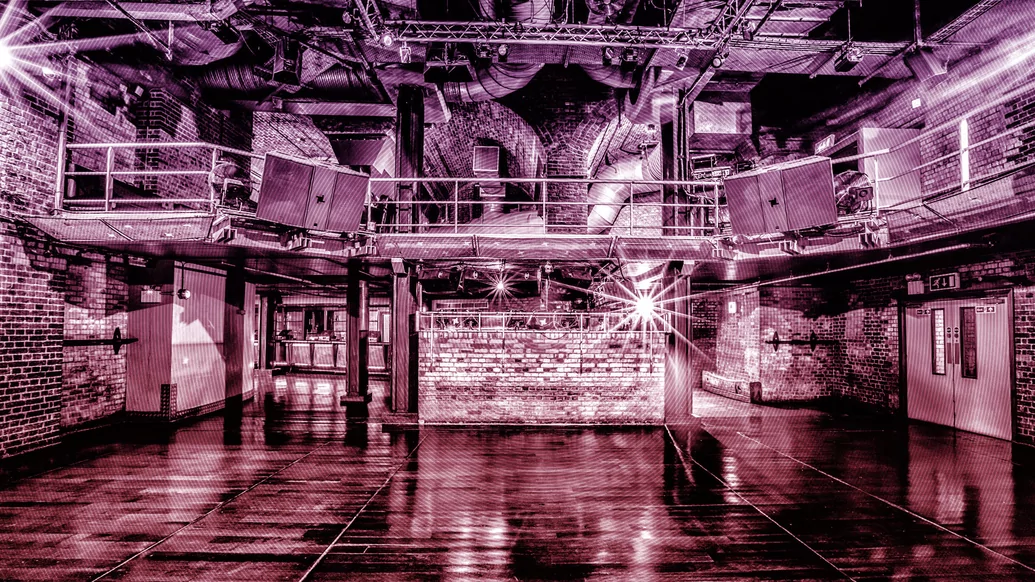

Since the beginning of 2017, every weekend, the metal walkways and staircases of Printworks, the 5,000-capacity venue in London’s Surrey Keys, have vibrated to sounds played by the world’s top DJs over a giant D&B Audiotechnik sound system. The five-storey-high main hall of the former newspaper printing press complex, which had become a key venue for electronic music fans, fell silent in March this year, when the doors were forced to close because of COVID-19 restrictions.

Now, Broadwick Live, which owns and operates the venue, has made one third of its full time workforce redundant and is fighting for survival along with thousands of other companies in the live music sector. “The uncertainty is the worst thing,” says Bradley Thompson, the managing director of Broadwick Live, which owns four venues in London as well as Depot in Manchester.

“We don’t have a date for when we are going to reopen, and we don’t know exactly what criteria they are going to use when decisions are being made about who gets government grants. Even if we get the grants that we have applied for, it’s not going to fill the hole left from our normal revenue streams.”

As the music industry has rapidly contracted, leaving thousands without work, the government has been criticised for failing to do enough to support the sector and those who work within it. Much of the criticism has focused on the way that the rescue packages and support measures have been structured: generally favouring big businesses and corporations over sectors like the music industry, that are mainly made up of small and medium-sized businesses and have a high number of freelance workers.

Doubts about how much the government is willing to support the UK music industry increased on 6th October, when the chancellor Rishi Sunak suggested that musicians and music industry workers should retrain and find different jobs. The suggestion has angered many: The UK’s music industry is the second-biggest in the world (after the US), and, along with Sweden and the US, the UK is one of just three countries globally that is a net exporter of music.

According to UK Music, an industry-funded campaign group, the sector was made up of more than 191,000 jobs in 2018 and contributed £5.2bn to the economy in terms of general value added (GVA), a measure economists use to evaluate productivity. Prior to 2020, the music industry was on-course to see continued rapid growth across all segments, from music creation, to retail, recording and live events — but this growth stopped suddenly in March this year when lockdown was introduced.

In a report published in July, economic forecasting company Oxford Economics estimated that the number of jobs in the sector will be reduced to just 77,000 in 2020, a drop of 60 per cent compared to 2018. The report estimates that the sector’s contribution to the economy would drop by $3bn, with the collapse in live music and touring being the single biggest factor contributing to the decline. The report also says that live music would be effectively “decimated across the whole of 2020” and anticipated that recovery would take at least three to four years to return to 2019 levels.

THE BIG BUSINESS BAILOUT

On 17th March, the government launched its Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF), a scheme to support large companies that make a “material contribution to the UK economy”. The scheme allowed large corporations to issue commercial paper, a form of debt that is then bought by the Bank of England, injecting cash into the companies. All of these loans come with extremely low interest rates, between 0.2 to 0.6 percent.

Smaller businesses that are not eligible for the CCFF loans were left to scramble for government-backed funds through commercial banks, with less favourable terms and interest rates of up to 6 percent. The CCFF loan scheme has been heavily criticised after it was revealed that many of the large corporations using them have been paying out billions to their investors in the form of dividends, while cutting jobs in the UK at the same time.

On 4th August, Vice News reported that 30 percent of the companies that were accessing emergency funds through the facility had paid out an estimated total of £11.5bn in dividends to shareholders and investors. These included the American oil company Baker Hughes, which accessed £600m from the CCFF in April and paid out the equivalent of £91.9 million in dividends on the 23rd June.

The UK-based budget airline EasyJet has also been criticised after it accessed £600m in government funds from the CCFF in April. Only a month before, on 20th March, it had paid out £174m in dividends to its shareholders, including £60m to its billionaire founder, Stelios Haji-Ioannou. In July, it was reported that EasyJet was using sickness records to determine job cuts of up to 4,500.

Other bailout loans have raised concerns because they were received by companies that have links to tax havens. These include £600m loans to the equipment manufacturer JCB, whose parent company is located in the Netherlands, and the fashion brand Chanel, whose parent company is based in the Cayman Islands.

IRRESPONSIBLE COMPANIES

The economic think tank Common Wealth believes that the UK government has made a mistake by directing so much emergency funding towards large corporations without attaching conditions that require them to improve their business practises. “Many of these large corporates have behaved irresponsibly, paying low relative rates of income tax, polluting the environment, and giving out massive dividends to investors,” says Adrienne Buller, a senior research fellow at Common Wealth.

“Part of the reason they have been given so much financial assistance is that the government is fixated on a very narrow definition of productivity. It also seems to have failed to recognise the benefits of having a diversity of company sizes,” she continues. “This isn’t good for the arts or for industries like social care, which is why both of them are so devalued. Rishi Sunak’s suggestion that artists should retrain gives you an idea of what is understood by the government as a valuable and productive sector — and it isn’t the music industry.”

Sarah Arnold, a senior economist at the New Economics Foundation, also believes that the government has made a mistake by focusing its assistance on big corporations and failing to attach conditions to the bailout loans as other nations have. “We have an unprecedented situation with this pandemic and we need an unprecedented response from the government,” she says. “It’s not about picking certain industries and picking certain people to support. You need comprehensive and universal support, both from an ethical point of view and from a macroeconomic perspective.”

According to Arnold, if the government fails to give broader support to companies and workers, there is a danger that the current recession could spiral out of control — becoming far deeper and wider. “If we see businesses permanently closing down because of the current crisis there will be economic scarring and a long-term depression of output,” she says. “This can be avoided if those businesses are supported through this time.”

“It’s been really stressful and we still have no idea what is going to happen after April next year... After watching the chancellor speaking publicly on television about musicians retraining, I dread to think about what officials are saying behind closed doors.” — David Whittall, Suki10c

MUSIC INDUSTRY COMPANIES

While international corporations have been accessing billions of pounds in unconditional bailout money through the UK’s CCFF scheme, many smaller companies within the UK music industry have struggled to access government support. Bradley Thompson, the managing director of Broadwick Live, says that it has been difficult to obtain financial assistance through official channels.

“Aside from accessing the furlough scheme we’ve had nothing so far,” he says. “The high street banks made it very difficult for us to access the government loan scheme and we were eventually knocked back. The government said it would be simple to access loans through the banks, but in the end none of them could help us.”

As a consequence, the company has been forced to refinance and shareholders have had to put additional capital into the business. Broadwick Live is still waiting to hear whether it is going to be given assistance through the £1.57bn Culture Recovery Fund. While the first batch of Culture Recovery Fund awards for venues was announced on 12th October, venues that asked the fund for more than £1m are due to be told whether their application was successful on 16th October.

“My biggest fear is that the government committee will look at electronic music venues and won’t give them the same weight as some of the institutions that have a longer history like theatres and traditional concert venues,” says Thompson. “Funding from the Culture Recovery Fund could give us a chance of weathering the storm, but even if we get to the other side we are going to come out saddled with a huge amount of debt that we didn’t have before,” he continues.

“If we can’t reopen, it won’t just impact us but the hundreds of freelancers and suppliers that depend on us for work. It will impact the supply chain, the musicians, and ultimately tens of thousands of people who attend music events at Printworks and Depot Mayfield every year.”

GRASSROOTS PROBLEMS

Many grassroots venues have seen even less government support. The Birmingham electronic music venue Suki10c, which is run by David Whittall and Kitty Barnes, has a capacity of 180 and was refused access to almost every form of government support over the first six months of the crisis. Over a period of eight years, the owners of Suki10c had transformed the premises from a dilapidated building to a thriving community hub and commercial success.

“It’s just heartbreaking,” says Whittall. “This year was set to be our best year on record. We started the year fully booked for the first six months.” The low-ceilinged venue has a large, analogue Martin Audio vintage sound system and regularly plays host to nights put on by up-and-coming DJs, accommodating a wide range of music genres from gabber to psytrance, hard house and speed garage.

“One of the things that artists and customers always comment on is how big the sound is,” says Whittall. “When you're in the club, you’re not here to have a chat with someone.” Suki10c also prides itself on its ethical stance. The venue uses 100 percent renewable energy provided by the company Ecotricity as well as recycling 90 percent of its waste. “During the early years, it was a hard struggle taking a building that had been in disrepair for so long and turning it into a thriving venue — but it was also a very rewarding process,” he continues.

Whittall and his partner are the venue’s only two full time employees, usually tending the club’s bar themselves at the weekends and employing freelance glass collectors. Despite building up a successful business over a period of eight years, they weren’t given access to the government’s furlough system as they weren’t paid through the PAYE system. They were forced to access Universal Credit instead.

They also tried to apply for a £25,000 grant for the hospitality industry, but were told that because their business rates valuation was below £15,000 they were ineligible. In the end, Suki10c did manage to obtain a small business support grant of £10,000, but it didn’t come close to meeting their costs and they were forced to raise extra money by asking their regulars for money in a crowdfunding campaign. “We raised around £4,500 in donations,” says Whittall. “Those donations and the messages of support from our customers were the only things that were keeping us going.”

Suki10c was told that its application to the Culture Recovery Fund was successful on 12th October, which means the venue will be able to survive until April next year. “It’s been really stressful and we still have no idea what is going to happen after April next year,” says Whittall. He’s concerned that the government doesn’t value venues like his own compared to other sectors of the economy. “After watching the chancellor speaking publicly on television about musicians retraining, I dread to think about what officials are saying behind closed doors,” he says.

If a large number of grassroots venues are forced to shut down because of COVID-19 it will have negative repercussions for the music industry as a whole, according to Whittall. “These venues are a space where the UK’s future stars hone their skills and creative innovation occurs,” he says. “A lot of the UK’s huge global stars started off as unknown artists in tiny little venues like this.”

Michael Kill, the chief executive of the Night Time Industries Association (NTIA), noted how only “very limited numbers of dance music clubs and events” were given grants from the Culture Recovery Fund on 12th October. Some of those include Columbo Group (who own London’s XOYO, Phonox and the Jazz Cafe), with £900,000, Ministry of Sound, with £975,468, Electric Brixton, with £623,000, Warehouse Project, with £343,000, and Corsica Studios, with £407,764.

“We have been aware all along that the fund would not be able to support everyone, and will leave many businesses who have missed out on this opportunity waiting on a perilous cliff edge, which will result in further redundancies in the coming weeks,” he says.

FREELANCE WORKERS

Workers in the music industry have also been hit particularly hard because the sector uses a large number of freelancers, many of which are not being given financial support during the ongoing crisis. A total of 72 per cent of those working in the music industry are self-employed, according to UK Music.

These workers will not benefit from the £1.57bn government funding package for the arts, and many of them are not being supported through the government’s self-employment support scheme. Around a third of self-employed people that have applied for government support through the scheme have been told that they are not eligible.

Caroline Norbury, CEO of the Creative Industries Federation, thinks that the music industry could be weakened over the long term if freelancers are forced to retrain and move into other sectors to try and get through the COVID-19 crisis. “There is a whole raft of different creative industries where freelancers have been badly affected and the music industry is amongst these,” she says. “This crisis has exposed a need for greater protection for people that are self-employed.”

“It’s devastating to look at the state of the music industry right now. I got into this business 20 years ago to put on parties, not to tell people to sit down. The government is being extremely slow, they’re not being proactive, and they are not making the most of modern technology.” — Stuart Glen, The Cause

SETBACK, OR PERMANENT DAMAGE?

Changing the way that freelancers are treated is just one of many measures that could improve the music industry’s chances of being able to bounce back from the pandemic. Other factors impacting the sector are the survival of small music businesses, and national efforts to implement an effective test and trace system to try and control the virus.

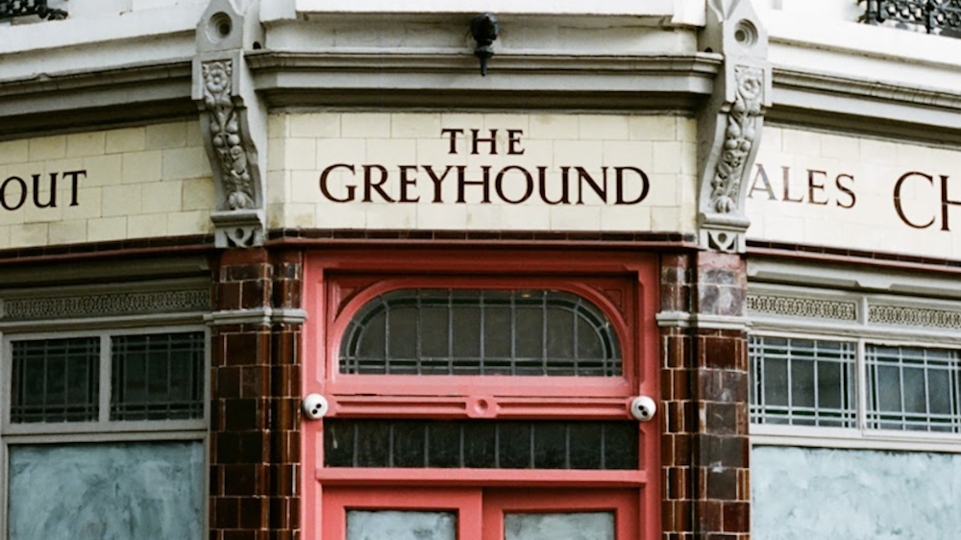

While venues and festivals only make up about one-fifth of the economic value of the UK music industry, their importance to the international success of British music shouldn’t be underestimated, according to Stuart Glen, the owner of The Cause in London. “Live music and clubs are one of the engines that powers the rest of the music industry,” he says.

The Cause was expanding when restrictions were introduced in March. They lost a significant amount of money, including a deposit on a new site, when it had to change its plans to adjust to lockdown. The venue was able to furlough a few staff, but otherwise got no assistance from the government. “Because the landlord’s rateable value was too high and there were multiple tenants in the building, we weren’t eligible for the grants we wanted to apply for,” says Glen.

He launched a crowdfunder that made around £23,000 to support the venue and used the money to overhaul its outdoor area. “We’ve expanded by doing live shows, comedy and brunch events to simply get the revenue in. It’s not as underground as it once was, but we still put on good DJs every Friday and Saturday to support the industry.”

Glen admits that while The Cause has adapted to survive, it’s no longer fulfilling its original purpose. “It’s devastating to look at the state of the music industry right now,” he says. “I got into this business 20 years ago to put on parties, not to tell people to sit down. The government is being extremely slow, they’re not being proactive, and they are not making the most of modern technology,” pointing to the UK’s lack of an effective test and trace system.

With the possibility of new restrictions being imminently introduced to try and reduce the severity of a second wave of COVID-19, the outlook for businesses and workers in the UK’s music industry is uncertain. Decisions made by the government over the next six months will be a key factor in determining whether the pandemic is just a temporary setback for the UK music industry, or something that it never fully recovers from.