At Home With: Jas Shaw

Simian Mobile Disco’s Jas Shaw deals in machine-driven techno delicacies, as his recent ‘Exquisite Cops’ solo album demonstrates. But having swapped the urban surroundings of Hackney for Kent five years ago, his studio is now an orchard-backed electronic eden that’s helping him recover from illness

We’re driving through Faversham, an unassuming Kent market town, with Jas Shaw, who’s telling us about the first visit he and his partner Jess made to the house they ended up buying five years ago. Traffic is normal, a scattering of four-wheel drives among small runarounds. But when they came, he says, there were scores of tractors on the road loaded with hessian sacks. Some of them looked like they’d seen their best days in the 1950s and many were driven by teenagers.

“It was hop season,” he explains, now filled with local knowledge, “which is the three weeks in the year they take them and put them in this big oast house.” For a couple of parents on a scouting expedition from Hackney, it was a mystifying spectacle. “Me and the Mrs were like, ‘What have we done?’”

Barn Cottage is probably not what you’d expect Jas Shaw’s techno headquarters to be called, although it is an accurate description. This is the man who, as one half of Simian Mobile Disco, defined East London electro with hits like ‘Hustler’. He’s a paid-up member of the international techno consigliere, playing Panorama Bar solo a couple of weeks before we meet, and has just put out his first solo album, ‘Exquisite Cops’.

Eight of the album’s 25 tracks were made last year while being treated for AL amyloidosis, an extremely rare disease for which he received chemotherapy. It is techno, however, that at least partly brought him here.

When he and James Ford, his SMD partner, had to look for a new London studio, options were either too expensive or destined for conversion into luxury flats. With two sons approaching their teens, Jess had already been suggesting moving out of London.

“This was literally the first place we saw,” he says on how easy the moving process proved. “She said, ‘We live there, and that’s your studio’. I barely needed to look inside. ‘Cool, let’s do it’.” A rebrand of the name was briefly considered, but Jess pointed out that “whatever you call it, it’s still twee as fuck.”

Shaw shoots down any romanticised views we suggest about living in the countryside (“It’s kind of a mixture of idyllic and bleak,” he replies, when we ask if the kids love it), but the cottage, which turned out to be almost the same size as the Hackney home they left behind, looks alluring to city eyes. There are tomatoes growing in the front garden and a gang of chickens out back.

Reggie the rooster was thrown over the fence one day by their ex-police neighbour, whose hobby is now buying fertilised chicken eggs off eBay. The cottage is the family domain, but the long, two-storey barn is Jas’ musical cave.

TECHNO HOLE

Despite insisting it’s Jess who is the more sociable one, Jas is warm, engaging and constantly interested, making us a morning coffee as he talks us through the barn’s history. It was two garages and a storage room for lawnmowers when they got it, with no floor and dodgy wiring. Transferring his musical tinkering to DIY, he couldn’t help getting involved with the builders, pointing out the floorboards he sanded, treated and waxed. “Just noddy stuff like that,” he adds with typical self-deprecation. “When they were doing the RSJ, I offered to help. But they told me, ‘You’re alright mate’.”

With a bathroom and bedroom downstairs, and a small recording room containing ad hoc instruments — a piano he bought for £50 and has begun to strip down to play through solenoids, a cracked cymbal to record through — the barn is a fully self-contained entity; a capability soon to be realised.

The real spectacle is the upstairs studio that fills the entire floor. Built from scratch with the help of a carpenter, it’s Jas’ working world. “I went overboard on the soundproofing because I was advised that if you don’t do enough, you can’t add a little bit at the end,” he says, explaining the process of having to build a room within a room to make sure nothing leaks into the quiet nights.

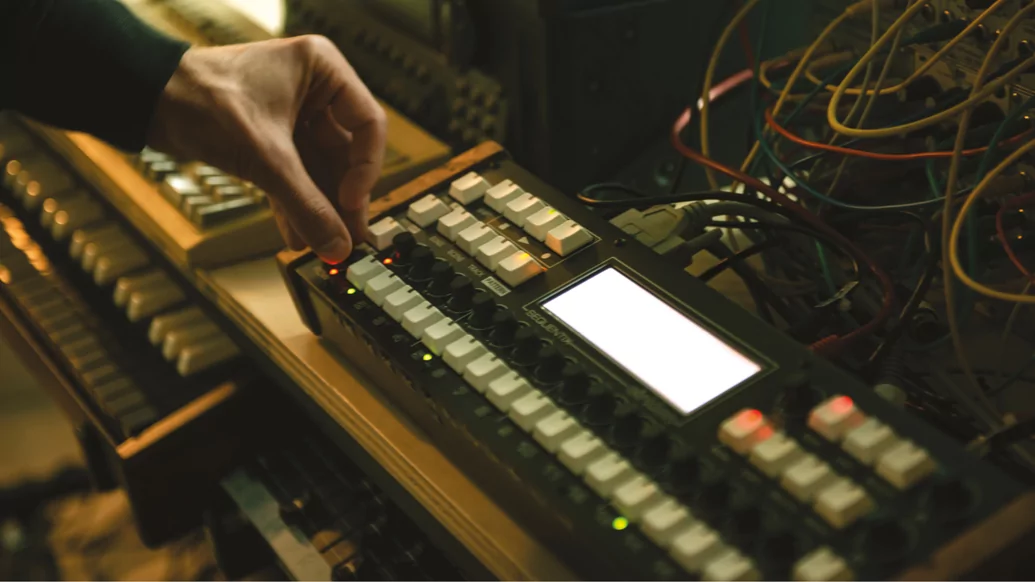

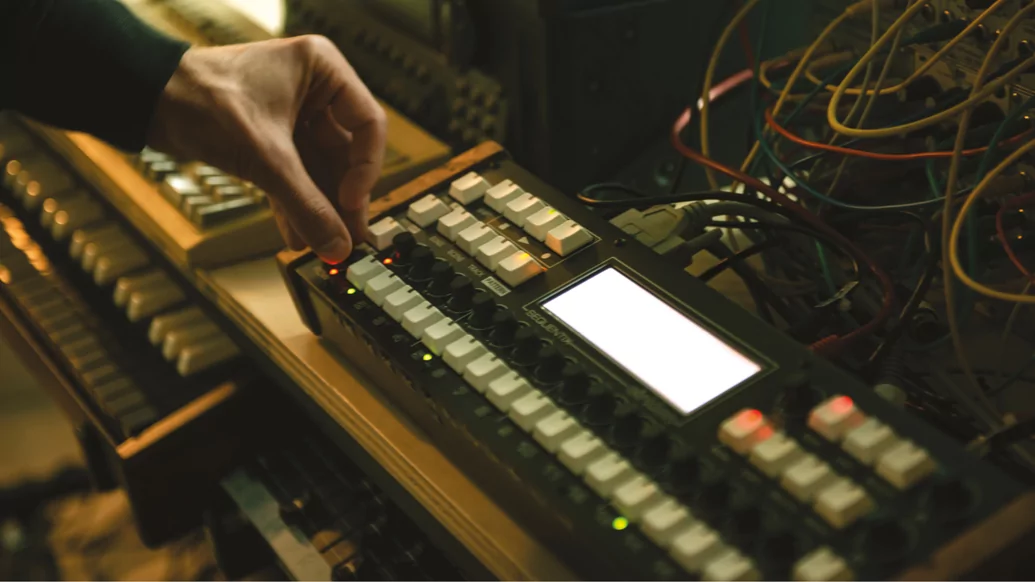

At one end is a live room and in front of that a mixing desk, separating giant Professional Series ATC monitors (“I think those monitors made me fall more down into the techno hole,” he admits). A rack of various modules sits alongside the desk, then the rest of the room is filled with an array of sequencers and modular synths, a section of more traditional synthesisers and drum machines — including a Roland SH-09, RS-09 and TR-909, Moog Prodigy and Sequential Circuits DrumTraks — confined to a corner at the back.

Despite starting out playing keyboards in Simian, the four-piece band that would become SMD, and whose track ‘We Are Your Friends’ became a global hit after it was remixed by Justice in 2003, Shaw almost dismisses each synth through its classic connotations: “This sounds like Kraftwerk every time you turn it on, this sounds like The Cure, this deals with all your New Order and Prince requirements.” He leads us to a giant unit of dials and wires built by a man in Scotland whose wife didn’t want it in the house anymore. One man’s loss.

“My job was basically to metabolise medicine. In a weird way, it was very focused. All I had to do was get some food inside me, see how long I could make music for, then sit back in front of the telly.”

”It works a bit like Lego, which is really satisfying,” he says, after an enthusiastic explanation of how the circuitry is made. “With software, it feels like you’re doing a spreadsheet,” he says. “Something like this is obviously fun.” A quest for hands-on fun over unengaged convenience pervades Shaw’s setup, as he breaks down the array of machinery around us: this cheap ’90s delay is Factory Floor’s secret weapon, that reverb gives instant Aphex Twin vibes.

A normal synth, he reasons, “does the same thing every time you come back. I’m the one that has to be creative, which is exhausting. With this you pull all the cables out, then when you come back, you plug it in again and it’s doing something completely different.” It might “spit out gibberish for a while, but then it spits out something that talks to a human”. This translates as less time spent thinking about musical structures and notation, and more time spent listening to what the sound feels like.

RECOVERY

‘Exquisite Cops’ captures his way of working. There’s a dancing interplay of trancey arpeggiated leads on ‘Freedom For The Pike’, undulating cloud-like melodies on ‘A Bird With No Feet’, and an infectious wiggly bassline on ‘Popes Of Dischord’. It also captures a specific time when the room became a place of rehabilitation.

In February last year, Jas was diagnosed with AL amyloidosi and almost immediately started weekly chemotherapy treatment, which lasted for about seven months. The process involved taking steroids to reduce his immune response. “The next day you’ve got this residual, slightly clubby manic energy. I can see how weightlifters have mood swings. I’d get angrier, then for two days after you get a comedown.” Netflix became a background to falling in and out of sleep on the sofa.

During the few days when his energy returned, the studio provided a sense of normality. “My job was basically to metabolise medicine,” he says. “In a weird way, it was very focused. All I had to do was get some food inside me, see how long I could make music for, then sit back in front of the telly.” Unable to make a whole track, as was his normal working method, instead he made components.

“I’d get a reverb out and make a weird pad and feed the reverb back into itself. It was something you could do in a few hours. The rule was rather than do it and abandon it, I’d record it.” Assembling these later into fully formed tracks inadvertently added the random element he thrives on. With this way of working, he began to create something different and new.

In January, he’s due a stem-cell transplant which will leave him neutropenic, meaning without enough white blood cells to fight infection, so he’ll be confined to isolation in hospital for around six weeks. Even when he goes home, he’ll potentially face months until he fully recovers.

“I’ll live out here because I’ve got two dogs and two kids. My house is lovely, but it’s dirty because of all the associated germs they bring back.” It sounds, by any standard, an extreme ordeal — his food will have to be in tiny packets and tins so as to not pick up bacteria — but Shaw is facing the unknown with a sense of adventure. He’s already planning what synths he’ll use to make his “isolation” record. “It’ll be ambient or furious,” he speculates.

SELLING

Heading for lunch at the local Sondes Tea House, we walk Macy, one of the family’s two rescued greyhounds, across the orchards behind his house, and pick pears to eat. After a short while, we reach a bridge, to cross the tracks at Selling. It’s the train station that lent its name to Shaw’s music partnership with Derwin Dicker, aka Gold Panda.

“Derwin loves this cafe,” he explains, “and liked the capitalist alpha male connotations of the name when the two of us are distinctly the opposite.” The project grew out of Derwin coming over to walk the dogs and drink tea. The music-making was almost an addendum to that, until their similarly blank-slate way of starting tracks began to yield something different from their solo work.

It’s a train line that goes directly to Elephant & Castle, where Shaw played a couple of gigs at Corsica Studios in the summer. “I’d get the second to last train in, then get the first train back. I’d be back walking home over the fields at 8:30am thinking, ‘Did that even happen?’”

This sense of unreality followed his diagnosis. It’s something that he’s had time to reflect on, he says, as we sit down to a selection of fresh country salads and bakes, the restaurant an eye-catching array of plants, mismatched furniture and bric-a-brac. “It’s random, which invites you to wonder. Was it when I did this all-nighter? Was it on a plane? The lifestyle I was living was quite extreme. It wouldn’t be unusual to miss two nights of sleep in a row, come straight back and look after the kids, which I loved. But there’s no question that it’s relatively punishing.”

Has he changed his approach to life? “No,” is the surprising reply that comes with a laugh, something qualified by the fact he is following his doctor’s advice on diet and exercise. But workwise he’s already tried producing other people or bands, and has settled on just doing music with people he genuinely connects with.

“Not because I’m shit at it or lazy, I just really don’t want it to become too work-obsessed. I can smell it when people are churning it out and doing what they know works. It’s demoralising, especially as you get older.”

If anything, Jas has gone the other way. From being in a band, where everyone has prescriptive instruments, to his countryside setup of strange machines, his method has been to open his creative process up to forces beyond his control. “It’s like any kind of art,” he says at one point. “You just need to create the conditions where something can happen. Then keep an eye out to see if it does.”

It’s an attitude that constantly replenishes Shaw’s excitement for the immediacy of modular music. “No one would want to be trapped in a room,” he says as we’re leaving. “But if you had to, this is a great one to keep you occupied. I feel like I might make a record.” And with Jas Shaw’s imagination, it’s the feeling that’s everything.