How Butterz changed the blueprint for independent UK labels

Since 2010, Butterz has been drawing a fresh blueprint for how independent UK labels can best function. As Jasmine Kent-Smith learns, Butterz founders Elijah and Skilliam have written themselves into UK dance music history books thanks to their close-knit, long-game approach

It’s 23rd September 2007 and Elijah, a young university student, sends a question to his friend, Skilliam, on MSN Messenger: “Wana be a DJ duo on crush uni radio?” They could never have guessed how far that question would take them.

After starting out as DJs, Elijah and Skilliam founded their blog-turned-radio show, label and club night, Butterz, in 2010. Looking at Butterz now, as they mark their 10-year anniversary, it’s clear that Elijah and Skilliam have led the charge: of grime music, first and foremost, but also garage and bassline — homegrown styles that rumble loud, wobbly and low across the UK. Their parties have played a key role in grime’s joyous return to the rave, pushing the genre years before its explosion into pop culture, and they’ve linked different artists to collaborate and tour, sending dancefloors into a frenzy.

There’s the funky multi-instrumentalist Swindle, alongside garage-meets-bassline producers and DJs Flava D, Royal-T and DJ Q (who operate together as the supergroup TQD). There’s Terror Danjah, Murlo, Champion and Newham Generals, the grime pairing of D Double E and Footsie. MCs like JME, P Money and Trim have linked with Butterz too, for radio shows, parties and releases.

Elijah and Skilliam run a compact operation, favouring sporadic, well-executed projects from a close-knit crew over an abundance of one-offs from, say, a producer of the moment — even when the instant gratification of a trend-led mentality could prove tempting, or financially rewarding. This approach has seen them through the late ’00s dubstep explosion and the early ’10s grime lull — which tempted producers, DJs and MCs away from grime and towards lucrative chart and club opportunities — the negative effects of Form 696 and the shuttering of London venues. Through it all, Butterz prevailed.

But back to MSN Messenger. When Elijah messaged Skilliam, they had been friends for some time. They joined their university radio station in 2007 and launched the Butterz blog to “continue where the other, original bloggers left off”, offering a resource for grime heads. (Grimeforum launched a year later, with Elijah as an administrator.)

“As a DJ, there was nowhere to play, so obviously, all the DJs that used to play grime moved to genres that they could get bookings for” — Elijah

In 2008, then-host of Rinse FM’s Grimey Breakfast Show, Scratcha DVA, told the duo that the radio station was looking for some new grime DJs. This was during what Elijah calls a “dark patch” for the genre; partly due to Form 696, a live music order form that was accused of unfairly targeting Black genres like grime.

“As a DJ, there was nowhere to play,” Elijah explains, “so obviously, all the DJs that used to play grime moved to genres that you could get bookings for.” Elijah and Skilliam were invited down to Rinse to record a pilot. They clearly impressed the station, as their first show aired soon after. Format-wise, there was an unwritten rule for how the grime shows were structured: vocal tracks were played in the first hour, and instrumentals with live MCs were played in the second. But since the duo didn’t plan on hosting many MCs, they stayed in the mix for two hours, blending instrumentals and vocal tracks. This may sound obvious now, says Elijah, but the only person really doing something similar at the time was Plastician, “but he was doing dubstep as well.”

They mixed new or unheard instrumentals with more “obvious” tunes so that the vocals “punched up” and created more impact. They approached popular vocal tracks from this impact-driven angle too, spinning the dubplate or less familiar edit rather than the original version. “If I lacked a big tune, and I could contact the producer, I’d say, ‘Hey, could you make a 140bpm version of this for us?’” Elijah says.

By the time they left Rinse in 2014, they’d hosted 300 shows that mainly focused on the producer side of grime. The show had built a solid reputation for them with fans and artists and they were tapped for ‘Rinse:17’, a 27-track salute to instrumental grime. The mix album was well-received by fans and critics. “We left Rinse because we wanted to focus on new challenges, like developing our event brand Jamz, the label and other personal projects,” Elijah wrote in a long Medium post back in 2017.

With a focus on grime’s sonics rather than its stars, the Butterz label launched in 2010 with Terror Danjah’s ‘Bipolar’ EP. They wanted to push grime but work in the style of broader electronic labels like Hyperdub, framing releases within evolving lineages and aesthetics in a way that felt unique, particularly to other grime labels — not that there were many. “The first few years flew past and we got a bunch of different 12-inches out. Most were well received and we eventually sold most of what we pressed,” says Elijah. “It was never a big earner, but any money we made we put straight back into developing the artists and projects.”

Swindle speaks highly of how the duo have run the label. “They never told us that we had to do something that we didn’t want to do,” he insists. “It’s about integrity, honesty and the intention for us all to win.”

In 2017, Swindle was working on his ‘No More Normal’ album for Brownswood Recordings. Even though it wasn’t coming out on Butterz, Elijah and Skilliam were part of the process. In fact, when Swindle and TQD were recording their albums, they were in the same studio, at the same time, albeit on different floors. “Those boys were in the studio when I recorded half the album,” Swindle says. “Recording at Real World Studios was actually Elijah’s idea.” Elijah laughs when he remembers this: “I was bouncing between floors, between a literal live orchestra for Swindle and then bassline downstairs.”

On radio and through the label, Elijah and Skilliam offered a take on grime that they wanted to hear more of but couldn’t find elsewhere. Then came the raves. They saw a gap in the market they could fill: a party for inventive, instrumental-led grime that allowed producers and DJs to become the headliners, rather than focusing solely on live MCs.

They started out in Fabric’s Room Three in 2011. In Elijah’s words, the nights went well, or “good enough to be invited back”, at least. After a couple of parties the pair felt they were ready to give Room Two a go — but Fabric didn’t think so. “I was like, ‘Okay safe, we’re gone’,” says Elijah, laughing a little.

They moved to Cable, a two-room venue near London Bridge. Their residency in collaboration with Terror Danjah’s Hardrive label launched in August 2011, the same week as the London riots. “We weren’t even sure if it was going to happen,” Elijah remembers, “but once we got the all-clear, everyone came wanting to let loose.” Cable’s 800-person capacity room made Butterz “the biggest grime night at the time”. Cable also gave Elijah and Skilliam more creative control over their parties.

When they were at Fabric, they felt that they were simply adding to what the Farringdon club had already built, rather than being offered a chance to build something of their own. It wasn’t all smooth sailing, though. Cable often gave Butterz “random, middle of the month dates” where the club couldn’t get house or drum & bass acts in. They made it work, but there was little incentive from the club to elevate Butterz to stronger weekend dates: “Yeah, we never got any of those.”

"Because my introduction to garage was through old tape packs like Sidewinder, Butterz was the closest I've ever felt to experiencing something that I'd heard on those tapes” — Conducta

They also found themselves engaging in drawn-out back-and-forths about having dubstep DJs on their line-ups. At the time, artists like Flux Pavilion, Doctor P and others who played “tear-out” dubstep were hugely popular.

“We’d sell 800 tickets and Cable were like, ‘Look, if you put a dubstep DJ on you’ll sell 500 more without even trying’,” Elijah says. “Yeah, but we’ll get to that point if you just give us time with this thing of ours — and then, you’ve got another thing to add to the repertoire of what you’re doing at the club. It took time, but it was worth it in the end.”

In the early years, the crew would often play entirely their own material during sets. Swindle’s ‘Do The Jazz’ and ‘Forest Funk’ were produced specifically to be played at Butterz. They also treated the parties as intimate hangouts for nerdy fans as much as blow-outs for ravers — especially at the beginning, when the crowd was full of people who had bonded through online forums, and would travel from different UK cities to meet up.

This connective aspect is something Elijah’s very proud of. He’s got a framed picture in his house of people who had come to Butterz parties from “all over the gaff”. “We used to finish at 5am, then the first trains home weren’t until like 6 or 7am,” Elijah remembers, “so everyone hung out afterwards. We’d go to McDonald’s in London Bridge — like 30 or 40 people! Once we had done maybe the third or fourth party, people started coming from abroad, too.”

When that happened, Elijah knew they were onto something.

In February 2013 Butterz celebrated the label’s third birthday at Cable. Former DJ Mag cover star Conducta was in the crowd. “It was Joker b2b Swindle and BBK came out,” Conducta remembers, his infectious grin beaming. “It was mad, there were whistles and vuvuzelas! Because my introduction to garage was through old tape-packs like Sidewinder, Butterz was the closest I’ve ever felt to experiencing something that I’d heard on those tapes.

Butterz inspired his own label, Kiwi Rekords — the way Conducta pushes innovation in UKG, in practise and style, isn’t too far from what Butterz have done in grime. “That’s what makes them special,” Conducta says. “They were able to capture something familiar and classic, but present it in a different, new context.”

That May, Butterz was dealt a devastating blow. Cable was to close with immediate effect following a legal dispute with Network Rail. It was one in a string of club closures across the capital at the time. They moved to Dalston basement spot The Alibi and called their new party Jamz; an intimate, more regular Butterz offshoot that they’d host in different UK cities. In November, they returned to Fabric as residents, and they found the club and “everything around it” ran far smoother than before, which meant they could focus on becoming better DJs in a bigger room. How did it feel to return to the venue after stints elsewhere? “You have to remember that most London venues didn’t want this music because of Form 696, but Fabric was a way to be safe from that,” Elijah explains, referring to the venue’s established relationship with the police at the time.

“I respected the institution too. Fabric put us alongside other [dance music] brands that I saw as peers, rather than always being compared just to people from my scene.” Their residency is something Elijah is “forever grateful” for, as the opportunity to return helped them grow Butterz outside of London.

Speaking of which — rave-hungry students in the North of England loved Jamz. “We used to do Leeds on Tuesday, Manchester on Wednesday and Liverpool on Thursday, and at the beginning of the university terms we’d do two-week loops,” says Elijah. “So, we’d do that midweek run, play our normal shows on Friday and Saturday, then go North again.” Altogether, they put on at least 80 Jamz shows in four years.

Elijah got the distinct impression that no one else in the North wanted to focus on grime with the force that they did. When they started in Leeds, most student parties were pushing Majestic Casual-style tech-house DJs.

“We weren’t playing obscure music, but it’s hard to overstate how much that style of house music dominated throughout 2013-2016,” says Elijah. Jamz offered a danceable, fresh alternative in a relatively risk-free way, thanks to smaller clubs, mid-week listings and a “no set times” policy that kept things playful, with lots of b2b and extended sets.

The Northern parties also developed the Butterz sound. What Elijah feels has “become today’s version of bassline seemed to percolate early in Leeds, with Royal-T, DJ Q and Flava D all making regular appearances at the run of weekly parties we did at Wire in 2015 and 2016.” The sound of TQD today is indebted to this Northern party vibe: it’s an adrenaline rush, of course, but it’s bright and bubbly rather than all-out aggressive.

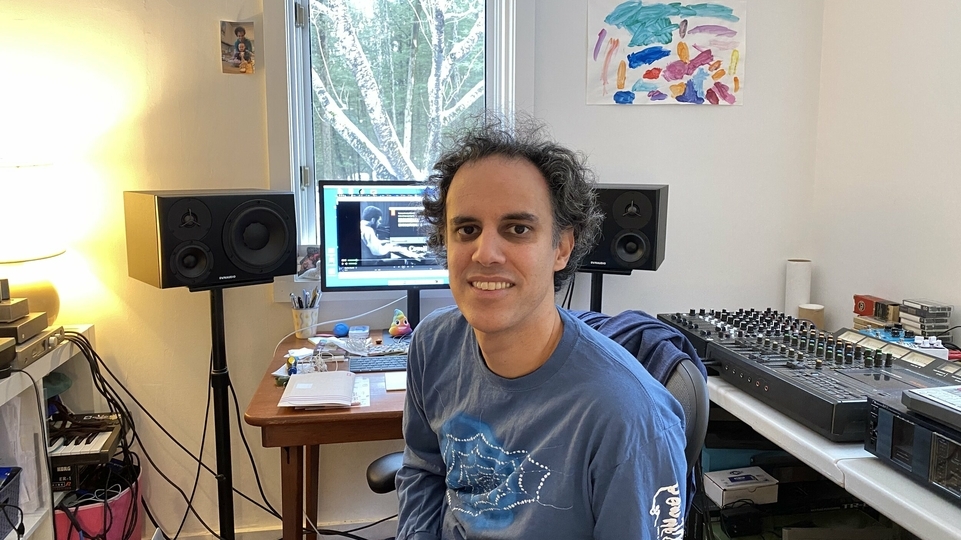

Along with radio, releases and raves, Elijah and Skilliam’s pragmatic approaches to business have steered Butterz. “I’ve never had an office. I still work from home,” Elijah says. “Some people have a PR person, a label manager, an office, this thing, that thing, and before you know it you’re running a full-blown operation to sell 500 12-inches. Skilliam packs the records. It’s not the most efficient way of working, but if we had all those extra things when the pandemic started then the business would be finished by now. But we don’t, so we’re cool.”

New people in Elijah’s circle are a rarity. When it comes to the label, dealing with the emotions and needs of a small number of artists feels more familiar and comfortable. “I feel a real personal responsibility when I put out someone’s record. I want it to impact them beyond just having a 12-inch in a shop,” he insists. “Putting pressure on myself to deliver that for people has maybe stopped me doing a record with someone that might have ‘done well’ in a particular scene.”

Speaking of ‘scenes’, Elijah admits that for “probably nine of the 10 years” they’ve had to argue that what Butterz did was dance music proper. Many took it as “just another form of rap”, despite approaching grime from a distinctly rave angle. They had to justify existing in the same space, or on the same line-up, as house and techno artists.

The duo’s legitimising moment came in 2014 when they released their ‘Fabriclive 75’ compilation. They offered those previously unaware or even dismissive of grime as an electronic music genre a sense of “where a certain corner of London was through the 2010s”, while showcasing some contemporary, innovative material. Bangers like JME’s ‘Integrity’ were tracklisted with music from a then-emerging Kelela, Murlo and the Butterz crew. The mix remains one of the few grime-focused offerings in the ‘Fabriclive’ series.

Through their journey from DJs and bloggers to radio hosts, label heads and club promoters, Elijah and Skilliam have changed the way that grime has been viewed in UK dance music culture. In staying devoted to the genre’s fundamentals while finding innovative ways to evolve, they’ve played the long game and are arguably winning.

What of their plans for the future, though? Well, 2020 has been a lot. Among many things, the year has offered them the chance to catch a breath, “after working and travelling for 10 years straight”. They’ve learned new skills and are working on new records. Some will be out on familiar formats on Butterz, some will be self-released, and others are collaborations with other companies and artists.

“There’s no rigidity in the way we work because we always want to do what’s best for the artists’ long-term wellbeing,” explains Elijah. “Staying small in terms of a crew has been part of our success, but having bigger ambitions individually and as a team will keep us going.”