How can clubs become more accessible for those with disabilities?

How can we make clubbing better for disabled people? When events return in 2021, clubs need to be more accessible for disabled guests and performers, who have often been left behind in progressive conversations within dance music culture. DJ Mag spoke to various venues — Fabric, E1, 24 Kitchen Street and Sheaf St — and disabled artist DeFeKT, about how clubbing can improve for all

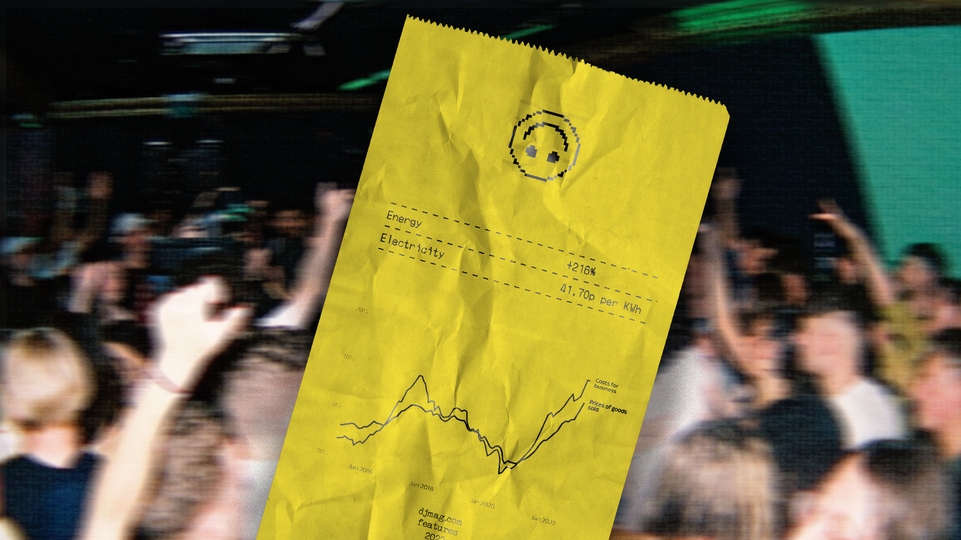

Dance music has never appeared to be more accessible. Despite clubs being closed for over a year, new crews and initiatives are constantly popping up, and many businesses have been involved in conversations around diversity and inclusion; some have published transparency statements on subjects such as anti-racism and gender equality.

But the harsh reality is that despite this renewed visibility for progressive causes, disabled people are still being left behind. As UK clubs prepare to reopen, the industry needs to reflect on what clubbing really looks like for disabled guests and performers, and what clubs can do to better welcome them in 2021.

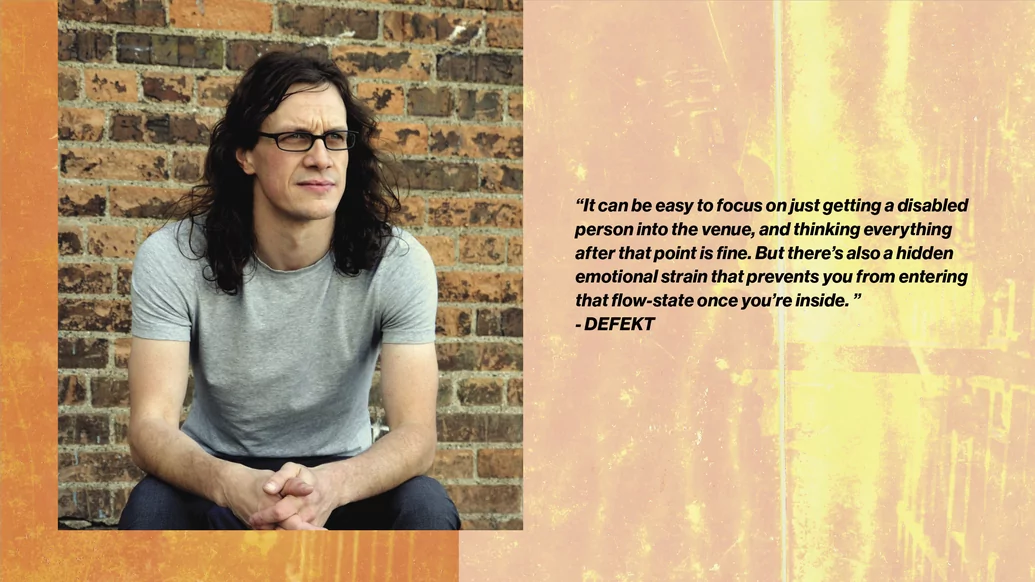

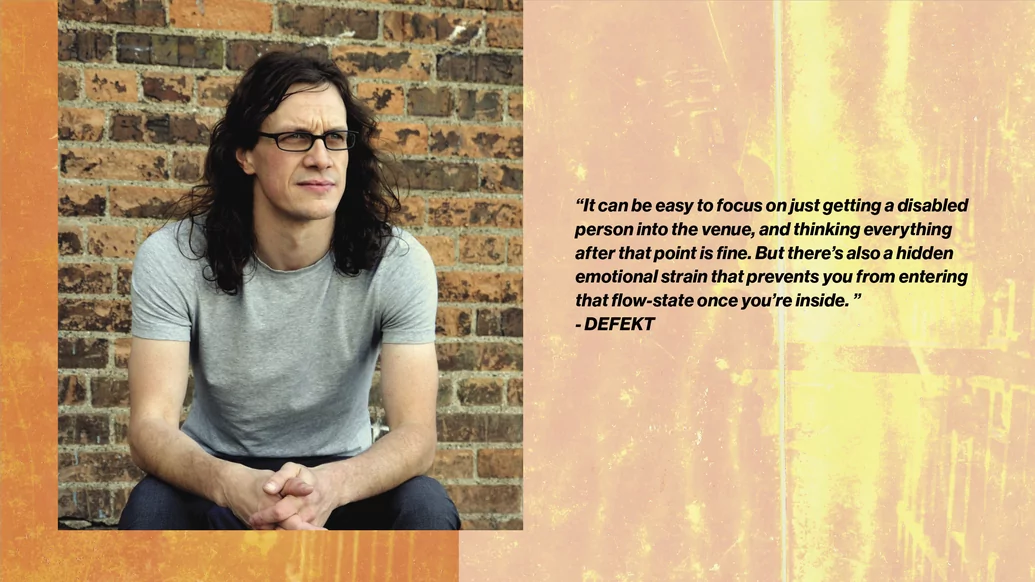

Matthew Flanagan DJs and produces electro as DeFeKT. With his curly hair and glasses, the Dubliner has become a recognisable face in booths from Berghain to Bassiani. In 2016, Matthew was enjoying a packed touring and release schedule — but everything changed that summer. He started having trouble walking, and chronic fatigue crept in. What felt like a bad hangover quickly worsened. After trying to hide his limp at a festival in Paris, a promoter commented that he was “walking funny”. Panic set in: “I had no idea what was going on with me, I was thinking it might be a stroke,” he remembers.

Matthew underwent tests and, in early 2017, was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, a condition that affects the brain and spinal cord. MS can cause a wide range of symptoms, including problems with vision, arm or leg movement, sensation, and balance. “I was in the studio when the doctor called me with the diagnosis, and I completely fell apart,” he says.

The news hit Matthew particularly hard because he’d seen the effects of MS first-hand, after his father’s diagnosis. “This was something I had been scared of my whole life, that I might be next,” he says. (While MS is not strictly a hereditary condition, having a close family member with MS increases your chances of developing the condition.) After a difficult year, Matthew realised. “I had a decision to make: I was either going to let MS control me, or I was going to follow my passion. Music saved me, because it gave me something to focus on beyond MS.”

In the past four years, Matthew’s career has been routinely obstructed not by his disability, but by his interactions with clubs, promoters and staff. Although he admits that he hid his diagnosis in the early days — when curious people took notice he dismissed his limp as a still-healing broken leg — he was nevertheless shocked at the lack of access available, which he also admits he paid little attention to when he was able-bodied.

He also found that the lack of visibility and knowledge around disabled performers led to some promoters being ill-equipped to help. “It was very difficult,” he says. “I needed help getting into the club, down the stairs, onto the stage, but there was none of it. I know that there’s some accessibility in bigger clubs, but in many places, once you’re through the door, they just fucking forget about you.”

So what do we mean when we talk about accessibility? The venues DJ Mag and Matthew spoke to represent a broad spectrum of UK offerings: from multi-functional pop-ups, like Liverpool’s 24 Kitchen Street and Leeds’s Duke Studios group (who run Sheaf St, and the soon-to-open TestBed), to repurposed historical buildings and purpose-built spaces, like London’s Fabric and E1. Capacities and budgets vary, but most of the staff have sought advice from Attitude Is Everything, the UK charity working to improve deaf and disabled people’s access to live music, and all want to do more to improve disabled access in their respective venues.

CARE

“What’s the single biggest element missing from clubbing for disabled people?” DJ Mag asks. Matthew’s answer is quick and simple — “care” — and he emphasises that this care is a multilayered approach. Simple tasks for able-bodied performers can be difficult and time-consuming for disabled performers. When Matthew lands at the airport, “I need help with my equipment from inside the airport, not just from the pick-up spot.” Then there’s the hotel: “What happens if I fall? Will I be able to use the shower? How will I get up to my room from the lobby?” riffs Matthew, counting off the concerns on his hands. Even going from the hotel to the club: I could need help right from the door of my room, and then after my set, having somebody bring me back to the hotel would make a massive difference.”

All four venues remark that they could look into building time into staff shifts for assisting disabled artists to and from their hotels. “For the staff to be trained in what someone like me might need during a night out would be a massive step,” he says. “I just need the club to be there for me if I need them”. Once inside the club, discreet, naturalistic assistance lets a disabled person know that help is there if they need it, and goes a long way to not making an individual feel singled out or different.

One suggestion references 2016’s Ask for Angela campaign, where guests use the phrase to discreetly signal concerns of sexual assault and harassment to staff. Venues could implement an industrywide phrase that allows disabled guests and their company to signal that nonemergency assistance is needed, without causing confusion or embarrassment.

OPENNESS

Luke Laws from Fabric asks, “How can the venues be more approachable when someone is at the stage where they don’t want to talk about their disability, like you were years ago? In that scenario, what can we do?” From this, ideas bounce around in the conversation: when clubs or promoters first contact an artist or agent for a booking, ask if the artist has any disabled access requirements; most will not need it, but being presented with the choice could encourage those living with disabilities to be more vocal, and normalise language around access in the booking process.

Many of the suggestions focus on technology. James Abbott from Sheaf St and Testbed notes that, as COVID-19 forced nightlife to adapt to social distancing by investing in app-based ordering services, this technology could be repurposed: to incorporate disability alert functions, or a live-stream from within the club, for those who can’t see or be near enough to the dancefloor.

Shirra Smilansky from Fabric suggests that, considering how large venues have a less evenly weighted ratio of staff to guests than smaller ones, the use of tracker-style medical wristbands or buttons, handed out to disabled guests on request, could alert the venue if the wearer needs immediate assistance. (Fabric already uses a simpler form of medical wristbands, but the other venues express interest in the idea.)

Jonas Roberts of 24 Kitchen Street brings up The Accessible Guide, a Liverpool-based startup that’s developing an app for venues to publish their accessibility features online. “It’s really positive to have information centralised and accessible, because that completely opens it up for someone with a disability where all that information is there already,” Roberts says.

This would allow disabled guests to check out a venue without having to email the staff days or weeks in advance of an event with questions about access, and could even put peer pressure on other venues to look honestly at their own accessibility. As Abbott puts it, “If other venues are resistant to this, a centralised app is a great way to show that this is natural, and if you’re not bothering to do this, then you need to catch up.”

On the point of emotional strain, Roberts broaches the subject of awkwardness: about bringing disabled guests in through a separate, accessible entrance, and the psychological effect that’s had on some of them. “It’s tough because it can make you feel different and isolated,” says Matthew, “but I think it’s the in-between care that matters more; making it feel as natural as possible.” Roberts agrees: the responsibility to create a fun, stress-free environment is on the venue, not the guest.

IN THE BOOTH

When looking out onto a packed dancefloor, an able-bodied person and a disabled person may see two very different scenes — one person’s thrill could be another person’s dread. Matthew knows how exclusionary a club layout can be, but this is not just about entrances and exits: “It can be easy to focus on just getting a disabled person into the venue, and thinking everything after that point is fine. But there’s also a hidden emotional strain that prevents you from entering that flow-state once you’re inside,” he continues. “When I’m trying to get lost in the beats, I’m really just thinking about getting around.”

The booth can be the most awkward area. Matthew uses a cane to walk, and finds it difficult to stand unaided for long periods of time. “Most clubs wouldn’t supply a chair to sit on while playing, or if they do, it’s a bar stool, which can be dangerous,” he says. “I don’t want to be afraid of falling during my set. Even having one high chair in the venue, with a backrest and sides, could make it much better.”

We next raise a common quirk — how to go to the bathroom mid-set. Everyone’s heard of DJs putting on an extended remix, and making a run for the bathroom. But for a disabled performer, dashing through a packed crowd isn’t possible. “If a club had a bathroom near the DJ booth, that would be one less thing I would have to worry about,” says Matthew. Speaking about Testbed, which is still being built, Abbott says that “putting a bathroom near the DJ booth is a great idea that benefits everyone”.

DESIGN ELEMENTS

While many clubs do now have wheelchair access at entrances and exits, everyone agrees that not all disabled guests use a wheelchair, that ramps are rarely inside clubs, and, even for non-wheelchair users, stairs can be a discomfort. “I don’t understand why it’s so difficult,” Matthew says. “Why can’t clubs just put ramps in place of stairs?” A removable ramp could provide access without permanently altering the building, and is particularly useful for multipurpose spaces. “We hadn’t considered a removable ramp before, but it’s definitely something we’ll look into for 24 Kitchen Street,” Roberts says.

Installing more ramps isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution, though. Fabric’s 96- step descent is mitigated by a lift, but on the rare occasion when it’s not working, given the steep gradient of the steps, the club becomes totally inaccessible for disabled guests. “It’s extremely tough because we are doing the best we can, but if the lift is broken it can take months for parts to be imported and fitted, and because we’re a heritage building we can’t build a secondary lift as a back up,” Laws explains. He describes the occasions where he’s had to tell disabled guests that the club is inaccessible as “some of the absolute worst times I’ve had working in clubs, it’s heartbreaking and awful”.

Subtle elements like handrails — near the dancefloor, bar, and toilets — also provide accessibility, but are rarely considered an important design feature. “If I want to watch a set or go into the crowd, the difference between a flat wall and a handrail is huge,” Matthew says. “Movable ramps and handrails are things I hadn’t thought about before, either,” says Abbott.

“We need to build clubs from the customer’s point of view. Adding handrails would be easy, something I could start doing straight away. I thought that it had to be all or nothing in terms of access, but it’s great to know that something small like handrails can make a big difference,” Abbott continues. “Matthew has shown us that it isn’t just about having a flat space to enter the building. It’s also about the softer things around that, and the care in between.”

Goodwill and conversation can enable progress, but changes to the design of a club can be costly. Roberts recently applied for an Arts Council England grant for 24 Kitchen Street, to construct a lift in their building. He’s found it difficult to get funding in the past: “We are a small venue run on a shoestring budget, and we want to improve accessibility, but it can be tough.”

Abbott agrees: “Now that people are more used to clubs demonstrating their cultural value, it’s important that we share knowledge about how to tick the right boxes for the people behind the funding.” Laws talks about Fabric’s experience in acquiring funding to make essential design changes: “Music Venues Trust have been instrumental in assisting us in acquiring all of our funding in the past; showing us, step by step, what needs to be done.”

COMMUNICATION

Gemma Middleditch from E1 notes, “We are quite fortunate, because E1 is all on one level, that we’re a really accessible venue, but it’s important that we make disabled people more aware of that. Otherwise, how else would they find out?” Abbott makes a similar, frank point: “There’s so many things that we do for accessibility that, thinking about it now, we don’t really tell anybody about directly. If the information isn’t out there, we might as well not be doing it.”

How then, DJ Mag asks, can clubs better communicate their accessibility? Suggestions range from including information on not just a venue’s own website, but also a venue’s listings on third-party websites like Resident Advisor, and social media accounts. The idea of creating a logo to signify accessibility was met with enthusiasm: “What would a logo that means ‘this is a disabled access venue’ look like, something universal and immediate?” we ask. All of the venues committed to clearer accessibility language in their promotions.

Throughout our conversation, everyone agrees that the solutions to a lot of the problems raised were simple, and could be enacted at no great financial cost to the venues, but the rewards of doing so could create a safe and more inclusive experience for everyone. “It’s just about seeing it from someone in my position’s point of view,” Matthew remarks, sagely.