How Paranoid London redefined acid house from their Hackney studio

Paranoid London are on a mission to bring back the rawness of old house, with their skeletal acid tracks and Chicago-influenced beats. We head to their Hackney studio to find out why they’re trying to put some sleaze and weirdness back in the music

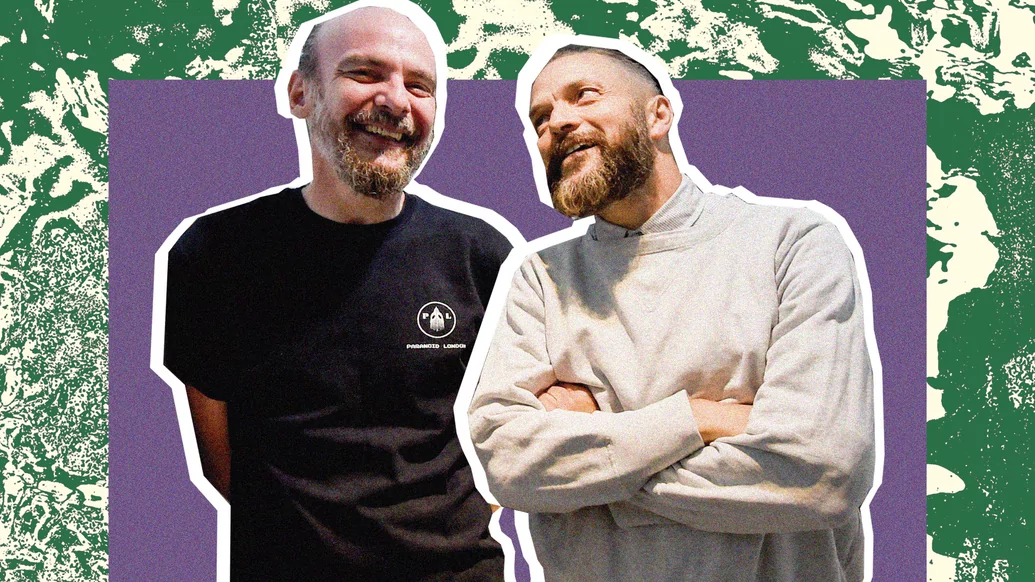

It’s not just the scorching temperature that’s causing us to sweat, as we wander around the back streets of Hackney trying to locate Paranoid London’s studio. There’s also a sense of trepidation about the duo. In the 12 years since Gerardo Delgado and Quinn Whalley began Paranoid London, they've given few in-depth interviews and have maintained a scant social media presence. Old press releases of theirs feature comments like, “If you like your music melodic, deep, well-made and produced, jog on”, and in another, they refer to themselves as “grumpy old shitsticks.” It doesn’t exactly allay our fears of a potentially painful hour, trying to coax conversation out of two moody, monosyllabic artists.

Within a few seconds of entering their subterranean space, though, all is forgiven. The studio is filled with synths and drum machines. There's a Roland 909 drum machine lying on top of a pile of hardware that Delgado, known as ‘Del’, has lugged here from Tooting. He seems surprisingly relaxed for someone who has been stuck inside a baking hot train for an hour. Whalley, an amiable host, sits back in a chair, offers us a beer, and answers the obvious first question: why have Paranoid London ended their self-imposed media blackout now?

“Boredom!” he laughs. “We didn’t want to do the same as the last album, when we didn’t do anything. This time we thought we’d do loads of interviews to see how that panned out.”

BANGING

Paranoid London have reached a level of success that other acts with an army of PRs, a marketing budget, and a brand awareness strategy could only dream of. Their 2015 self-titled debut album brought their raw, jacking acid house style to fans who’d missed out on their limited edition 12”s. It’s a style that won over dancefloors, the electronic music press, and many of the world’s biggest DJs — some of whom fruitlessly begged Whalley and Del for free copies of the 12”s after being too slow to pick them up before they sold out — but also rock and indie-orientated media like Pitchfork and Rolling Stone. It’s propelled their live show to festivals like Glastonbury and Sonar, clubs like Trouw and Panorama Bar, and support slots for The Chemical Brothers and Soulwax. Not bad for a style that Del says is “nothing frigging clever — but it works.”

When they were starting out together, trying to be too clever was a problem for the pair. While living in Tenerife, Del made regular trips to London to produce music, and he was introduced to Whalley, an engineer at Fortress Studios following a stint as one half of Different Gear. Whalley had produced a 2000 bootleg of The Police’s ‘When The World Is Running Down (You Can’t Go Wrong)’ - a surprise clubland smash he’d now rather forget. They quickly became friends, but the music took longer to blossom.

“We’d sold a lot of equipment because computers were now quick enough to use in a studio,” Whalley says. “Del would sit there watching me draw patterns on a computer, and it got pretty boring. Eventually I was like, ‘I feel bad that you’re paying me to engineer, but we’re not releasing anything’.”

“We were chasing whatever was cool at the time — Danny Tenaglia, tribal house,” says Del. “It changed depending on the month. They were okay, but I come from the school where you don’t release anything unless you’re completely happy with it. There was never anything where I thought, ‘That sounds like us’.

“So one night I asked Del, ‘What do you really like doing?’” Whalley continues. “He said, ‘Banging out acid house’, and I was like, ‘Funnily enough, me too!’ So we went and got the original bits of equipment back [out]. We were suddenly doing tracks in three to four hours. Del didn’t care if nobody liked it, as long as we were making the records we wanted.”

FLASHBACK

Those records are flashbacks to rough and ready style of early Chicago house music: tracks by Marshall Jefferson and DJ Pierre, and played by Ron Hardy at the Muzic Box; records that were gradually appearing in UK record shops in the late ’80s, when Whalley and Del started buying vinyl. “When acid house came out, it just sounded so alien to everything else,” says Whalley. “My old man’s a musician and he couldn’t wrap his head around the fact that it was even music. A similar thing happened with electro and hip-hop — musicians couldn’t understand how you could make a new record from bits of other people’s. The Roland TB-303 didn’t even sound like music. It was absolutely brutal.

“There was also a big backlash against it,” Del recalls. “Hip-hop shops got the first house records, but whenever they played one, there was a big fuss — ‘Why are you playing this?’ I got abused for going into one of the best record shops in London, because it was a gay record shop. Trax and Groove were on the same street — Groove was a big hip-hop shop and Trax was [focused on] Eurodisco. I remember going in, and the kids outside called me every name under the sun. I thought, ‘Brilliant. If you’re that scared of this [sound], then we’re onto something’. A year later, they’ve all got baggy clothing on shouting, ‘Acid!’”

As a statement of intent, neither the title of their first release or the track itself could have been clearer. Released under the name One Last Riot, ‘We Make Acid’ looped veteran Chicago producer K. Alexi intoning ‘Acid’ over an intense TB-303 burble and thumping kick. It was the debut release on the Paranoid London label, which Del started in 2007. They later decided to use it as their artist name, in Del’s words, “to keep things simple.” “One Last Riot sounds like a punk wedding covers band,” says Whalley. The name also came from current events. Del was in London during the 7/7 terror attack. “When the bombs went off, the whole city had this really weird vibe,” reflects Whalley.

It was also inspired by the pride these two adopted Londoners — Whalley is from Stalybridge, Del is from Guildford — feel for their home. “Because of all the minimal stuff in Berlin, I thought it would be hilarious if every time you mentioned us, you had to say ‘London’,” Del elaborates. “There was a New York sound and a Chicago sound — this was the London sound.”

ORIGINAL VOICES

It was to New York and Chicago that their first two Paranoid London tracks looked, however. ‘Eating Glue’ had Mutado Pintado — an alias of London-based New York performer and all-round prankster, Craig Louis Higgins Jr. — murmuring sleazily over a bassline. All 300 copies sold out in days, but it was ‘Paris 1’ that really blew up. It featured Paris Brightledge, the voice of original Chicago house classics such as ‘It’s All Right’, who Paranoid London’s manager had tracked down online.

“All the early Chicago lot had been ripped off with really shitty record deals,” says Whalley. “We thought he was going to tell us to fuck off, but he was really up for it. But when we got him in the studio, we thought, ‘Rather than get him to do a house vocal, let’s get him to do something by The Fall’. So we had this legendary Chicago house singer speaking Mark E Smith’s words. Then he wrote the lyrics and melody for ‘Paris 1’, which was too good not to put out.”

With its sweet, spiritual vocal coupled with a colossal bassline, ‘Paris 1’ sounded as if it came straight from house’s halcyon era and was, as Del puts it, “two fingers up to minimal”. The pair didn’t want to just recreate the authentic sound of acid house, but also the whole experience of when discovering electronic music meant actually going to record shops rather than clicking online.

“When we were growing up, it was difficult to get hold of records you really wanted. The more difficult it was, the more you wanted it,” Del says. They decided to release their first records in limited edition vinyl runs, with no promo copies. “But it meant that you played the record for longer. When we put out a few hundred copies, you are one of only a few people to have it. It doesn’t matter if you’re a bedroom DJ or playing the biggest clubs in the world — if you can’t be arsed to go to the record shop, you can’t have it.”

Whalley and Del got plenty of emails from “massive DJs” — they won’t name names — pleading for copies, always replying with a flat ‘No’. Not that the pair are particularly impressed by many DJs in any case. They rarely step behind the decks themselves. “There’s lots of DJs where I think, ‘Jesus mate, you’re going to regret that in six months’,” Del laughs. “We’ve all been kids trying to be the new trendy bloke. We’re old now, so we’ve got our own sound, but when you’re younger you’re too busy trying to follow a trend.”

ROCK ’N’ ROLL

Paranoid London are in their element when they play live. When they debuting at The Warehouse Project 10 years ago, Whalley says that the chaos inside “set the mood for all the gigs that followed.” Their gigs are as much rock ’n’ roll as they are acid house, with Mutado bellowing out to the crowd at the front while Whalley and Del blast out beats at the back.

“The bits I loved about DJing was where it felt like the mix was going to fuck up at any minute, so we essentially run our live show like that,” says Whalley. “It is quite extreme. You can make a lot of noise with a few bits of equipment, and Craig makes everyone feel part of what’s going on — he’s passing the microphone around or grabbing people out of the crowd. He puts a whole different spin on it that takes it away from being two guys with a bunch of machines.”

Mutado is also among the cast of what Del calls “creatures of the night” on their new album, ‘PL’. Whether it’s legends like the late Alan Vega of New York electronic proto-punks Suicide and Simon Topping of Mancunian punk-funk band A Certain Ratio, or newer faces like Josh Caffe, their vocalists embody the extreme, of lifetimes full of lost weekends.

“You’ve got to try and scare the children!” Del jokes. “They are the freaks you really meet when you go out at night, so why not put them on a record? They’ve got better songs, because they’ve got more to say instead of a good-looking lad or girl going, ‘I love you baby’.” “We’re attracted to weirdoes,” Whalley continues. “Just because that’s the kind of circles we move in.” In the case of Bubbles Bubblesynski, the DJ and trans activist who was tragically murdered in San Francisco, it’s a choice that serves as a salutary reminder of a time when house music was a secret, a sound that welcomed those whose race, sexuality, and gender identities were largely unwelcome elsewhere.

“Acid house for me was never white kids with smiley faces dancing in fields in England,” says Whalley. “When I was DJing in my bedroom, I was always imagining it was a sweatbox in Chicago. Dance music has now got so big and homogenised, that there inevitably aren’t enough weirdoes to fill a 15,000-capacity festival. It’s inevitably going to be more normal straight people, so it is important to remember that it comes from a certain background. But we’re not really trying to make a statement. The whole point of the Bubbles track was to make something for people off their tits on Saturday night. Bubbles would have been really happy to have been on the dancefloor and heard his voice, while everyone was losing their shit.”

CLASSIC FORMULA

For Paranoid London, who happily admit to being oblivious to current trends, their formula for making people lose their shit hasn’t changed in 30 years. They’re adamant that the crackle and hiss of old records, what most contemporary producers would smooth out, is what makes their music feel human and alive. For a new generation of clubbers whose parents might have a few dusty copies of Frankie Knuckles records in the loft, Paranoid London’s sound may well feel fresh and exciting to hear.

“A lot of those old records were pressed really badly, so when you put the needle on the record, it went ‘kkkrrsshhhkkksshhhh’ — and that was really exciting,” Whalley remembers. “It sounded really sterile when it was clean, so the noises that come off these machines are pretty sexy, I think.”

“We just want to make those records where you’re like, ‘What the fuck was that?’” states Del.

“None of our records have got any intros or breakdowns. They just go on doing their thing, but with a massive bassline that always just gets everybody,” offers Whalley. “Nowadays, at lots of places that we play, it’s the first time there’s been a big bassline. Other records might have a bass ‘sound’ to them, but when we start going ‘Bom-bom-bom-bom-bom’ through massive speakers the kids go nuts for it.”

As Del says, it’s not frigging clever — but it works.