How producers can get paid through streaming services

Streaming has come to dominate the music industry, but when it comes to actually earning money from plays, the electronic music community has been somewhat left behind. We explore the different services on offer to find out how producers can get paid

Streaming is everywhere. Earlier this year, Spotify announced that it has 217 million users, more than 100 million of which are paid subscribers. They’re followed by Apple Music, which boasts 56 million paid subscribers and comes pre-installed on every iPhone in the world. YouTube dwarfs them both, with more than two billion monthly users. Additional players like SoundCloud, Amazon, Pandora, Deezer, Tidal and Bandcamp are all in the mix, and that’s just a partial list. Streaming is a growing, global enterprise, and its impact is reshaping the music ecosystem.

Electronic music does have some unique, partial immunities to streaming culture. It’s historically been delivered by DJs, so tracks are often designed with their needs in mind, as opposed to what’s best for a curated playlist. DJing requires actually possessing the music, and is usually collected in bulk, as even those DJs who are also producers rely heavily on tracks made by other people. Unfortunately though, widespread piracy means that many digital DJs aren’t paying for their music, and even when they do, it doesn’t generate much revenue for artists and labels – especially when online music stores generally keep at least 30% of the purchase price for themselves.

In truth, even that small group of active buyers is shrinking. Despite all the mainstream industry talk about vinyl’s resurgence, few labels are pressing up more than 300 copies of their new releases. Digital sales are shrinking, too, as fans migrate to streaming platforms. As a result, electronic artists – especially those who aren’t DJs – are seeing their primary source of income dry up. Ironically, we’ve reached a point where DJ fees have never been higher, yet the people who actually make the music are struggling to make ends meet.

Unsurprisingly, this has prompted some artists to seek out new revenue streams, whether it’s developing a DJ career, looking for publishing deals, or chasing corporate sponsorships. Expanding merchandise offerings is a popular choice – it’s no accident that seemingly every artist and label is releasing limited-edition streetwear these days – and of course there are syncs (ie. getting music licensed for use in advertisements, television shows, films, and video games).

CHANGING LANDSCAPE

“The landscape for labels is changing rapidly,” says Kris Jones, Licensing and Publishing Manager for Hyperdub. “Labels the size of Hyperdub constantly have to be looking out for new ways to diversify in the current climate, not just [in terms of] revenue streams, but how we work with artists, how the music is curated, released, promoted – everything.” He continues, “Any extra income for a small indie is important to invest back into the label, its artists and events... but nothing is guaranteed in the licensing world. We can go months without anything and then score three decent licenses in a month. It’s very unpredictable.”

There’s also potential revenue from streaming services, especially for larger indies like Hyperdub. “Streaming revenue is our biggest income [stream] for the label,” says Jones. Yet on the whole, electronic music is lagging behind other genres when it comes to knowledge of and engagement with streaming platforms. Many artists and labels are unaware of basic facts about how the streaming economy works, what these platforms pay, and how music even lands on the various sites in the first place. The payment issue tends to take priority in most people’s minds, and a lot of the news hasn’t been good.

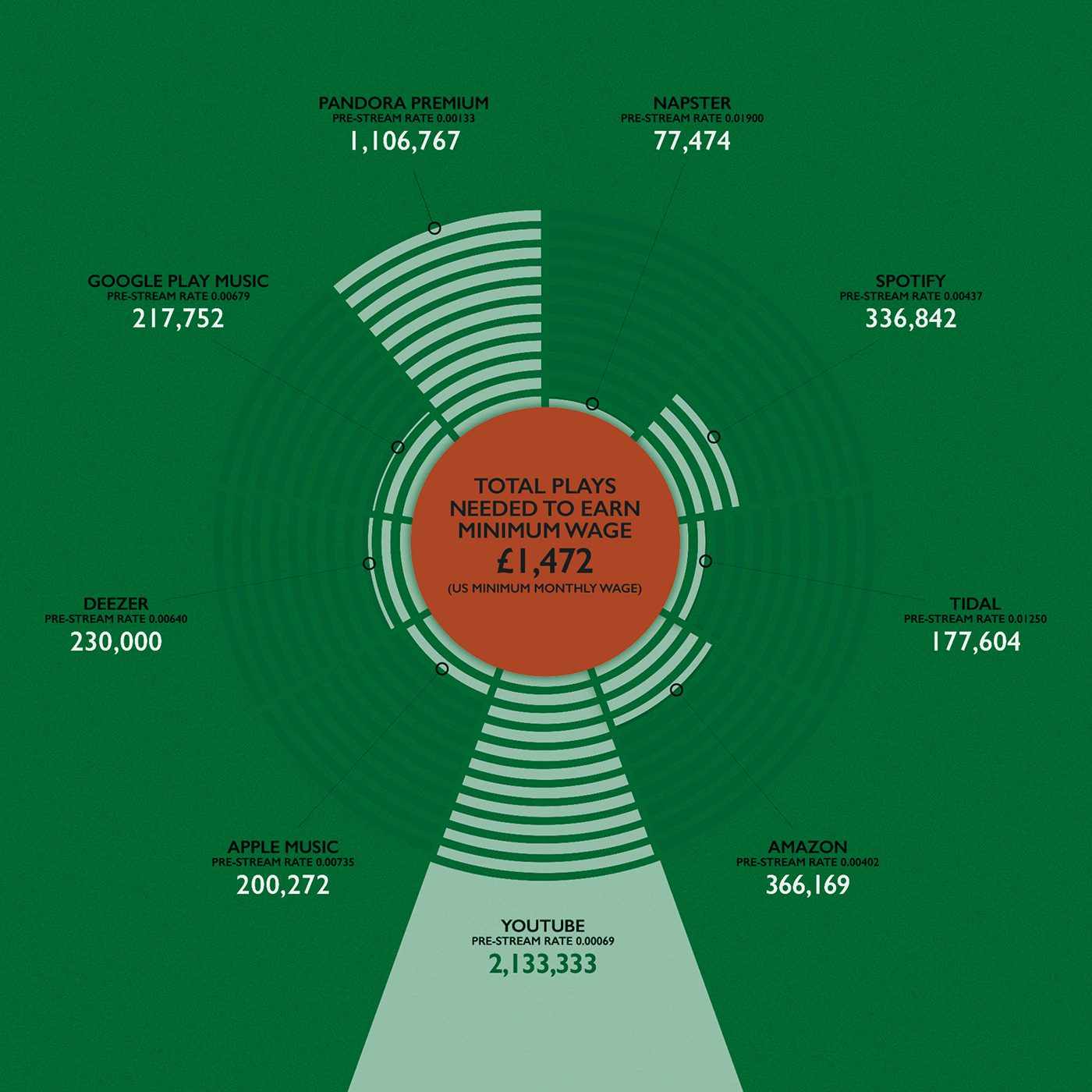

Streaming platforms are notoriously tight-lipped about their royalty and payout models, but it’s well known that they’re generally paying fractions of a penny for each listen. There are slight differences; Apple Music pays more than Spotify, which pays significantly more than YouTube. But regardless of the platform, the current system is one where artists with thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of plays, are receiving only a pittance – and that’s before their labels, managers, distributors, and other industry players have taken their cut.

THIRD PARTIES

Complicating matters further, to qualify for the possibility of earning, artists and labels first have to get their music onto streaming platforms. With few exceptions, it’s nearly impossible for artists to directly upload their music onto Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music, Amazon Music, Deezer, and most major streaming platforms. Spotify did beta test a program which allowed direct artist uploads, but elected to end it earlier this year. Even Beatport requires artists and labels to enlist a third party to get their releases in the shop.

Those third parties generally come in one of two forms: digital distributors and aggregators. The former are often outgrowths of physical distributors, which work directly with artists and labels to to sell physical records to shops globally; in the digital realm, they’ve expanded their business to include placement of music on online stores and streaming platforms. But whether or not these companies traffic in physical releases, the business model for digital distribution is usually straightforward: they take a flat percentage of all digital revenue, whether it’s from online sales or streaming.

Aggregators are a different animal. There’s some overlap with digital distributors – many aggregators see digital distribution as just one facet of a larger suite of “label services”, which revolve around marketing, promotion, and sync licensing – but these companies’ primary function is still placing music on streaming platforms. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of aggregators out there, each with its own features and specialties. Some, like AWAL, Stem and Symphonic, are selective, functioning like quasi-labels by working with artists they perceive as having a chance to make it big.

More common, however, is the open approach of outfits like CD Baby, Tunecore, DistroKid and ReverbNation. They will work with just about anyone, as long as the artist is willing to pay an up-front fee and/or surrender a percentage of any digital revenue. By casting a wide net and aggregating releases from large numbers of artists, they’re able to then work directly with big streaming outlets like Spotify and Apple.

However, few of these aggregators seriously traffic in underground electronic music. Many of the larger companies don’t even place music on Beatport, let alone more niche outlets. (Some of the aggregators that do work with Beatport include ReverbNation, Symphonic, Ditto, Label Worx, Horus Music, The Orchard, Fuga, and Dancephonic, amongst others.)

SELF CONTROL

For those looking to have more control over the placement and distribution of their releases, there are two major platforms that engage directly with artists and labels: Bandcamp and SoundCloud. The former isn’t a streaming platform per se, yet it has been broadly praised in the DIY music world. Bandcamp allows artists and labels to set up their own online stores where they can sell records, cassettes, clothes, posters, and pretty much any other kind of merchandise, along with digital files (in numerous audio formats, including Lossless, which isn’t an option at many stores).

Although streams aren’t always unlimited (artists and labels themselves make that decision) and the site’s offerings don’t match up with the expansive catalogues and star-studded campaigns of other platforms, its library goes deeper into niche styles. And unlike its larger competitors, some of which have racked up operating losses in the hundreds of millions, Bandcamp claims that they’ve been profitable since 2012.

Impressively, they’ve done this while granting artists and labels an unparalleled level of control in exchange for only 10-15% of revenue earned. (Consumers do pay an additional 4-6% payment processing fee for each purchase, and Bandcamp offers a $10 USD per month Pro tier, for artists and labels who want additional analytics and a fuller suite of site features.)

Although revenue from Bandcamp is 100% based on people purchasing music and music-related merchandise – no royalties are paid out for music streamed on the site – it’s hard to think of a better online outlet at the moment, especially for those looking to support independent, underground music. Its goals and services may have shifted over time, but SoundCloud was originally rooted in a similar community.

Much of the platform’s initial success stemmed from its role as a place where aspiring artists, producers, and DJs could post and share their work. While the company’s more recent efforts to monetise said work and comply with international copyright laws have resulted in various problems, and even more user skepticism, SoundCloud continues to be an important component of the electronic music landscape.

It’s still a place where artists can post their work for free, with additional features available to those who pay for a Pro or Pro Unlimited subscription. For those looking to monetise their music, SoundCloud has also rolled out its Premier service. Applicants must meet certain age (18+), copyright (no account violations) and popularity (at least 1000 streams per month) requirements, but those accepted to the program can earn revenue – although the payout rates are variable and unclear – and easily distribute their music directly to other major streaming platforms, which is handy for artists hesitant to link up with an aggregator or digital distributor.

SoundCloud’s services aren’t limited to artists, either. In 2016, the company launched SoundCloud Go, a subscription-based streaming service meant to rival the likes of Spotify and Apple Music. Although SoundCloud Go has reportedly been slow to find a foothold in the streaming market, the fact that the company’s library includes proper releases and a vast network of user-provided demos and mixes makes it an interesting alternative, especially for those in search of something beyond the mainstream.

STREAMING IN THE BOOTH

More intriguing is SoundCloud’s flurry of recent partnership announcements with Native Instruments, Pioneer DJ, Serato, Virtual DJ, DEX 3, and Mixvibes. Clearly looking toward a future where streaming for DJs is not just possible, but commonplace, SoundCloud is hoping to get ahead of the competition by teaming up with leading manufacturers of DJ hardware and software.

Technological concerns aside (eg. what happens when the wifi or cellular signal goes out?), the economics of this arrangement have yet to be sorted out. SoundCloud hasn’t provided any clear or specialised royalty regime for SoundCloud Go tracks that are played using DJ software or hardware. Legally, they may not even be required to do anything additional, making the streaming revenue for a song played at Fabric the same as it is for a teenager listening on their phone. (Of course, when a track is played at a club or music venue, the artist is technically owed a separate royalty from a performance rights organisation, but that’s a different regime with its own set of challenges.)

Beatport has also jumped into the streaming-for-DJs game, launching a subscription-based streaming service earlier this year called Beatport LINK. Like SoundCloud, they’ve partnered with Pioneer DJ, and additional partnerships with Virtual DJ, Denon, and others are in the works. Moving into streaming might seem like a risky move for a company whose business model has largely been based on selling electronic music, yet Beatport claims that LINK isn’t part of a larger scheme to ditch digital sales entirely.

In a recent interview with Create Digital Music, head of artist and label relations at Beatport, Heiko Hoffmann, said that, “LINK will provide an additional revenue source to the labels and artists. The people who are buying downloads on Beatport are doing so because they want to DJ/perform with them. LINK is not there to replace that.”

LINK (which costs $14.99 USD per month) is being touted as a service for beginners. It grants access to the entire Beatport catalogue, but at 128 kbps, it’s theoretically too low quality for professional DJs and soundsystems. For the more serious, there’s LINK Pro ($39.99 USD per month) or LINK Pro+ ($59.99 USD per month), which offer higher-quality 256 kbps AAC files – Lossless formats are not available – along with a “locker”, where DJs can download and temporarily store either 50 (Pro) or 100 (Pro+) tracks offline.

Beatport LINK is notably more expensive than subscriptions on other streaming platforms, particularly its professionally minded Pro tier. The company says this is intentional; although light on specifics, they claim the higher fees will result in a larger royalty pool, which would mean higher streaming payouts for artists and labels, and an offset against potential lost revenue from digital sales.

In that same interview, Hoffmann said, “Beatport’s per-stream rate is very likely to be higher than other streaming services: we are putting the lion’s share of the LINK revenue into label payments. Unlike other services the fee will not be shared with music from other more mainstream genres which make up the majority of most streaming services' payments.”

DIFFICULT REALITY

This sounds good in theory, but it’s difficult to evaluate without more specifics from Beatport or robust, real-world reports from artists and labels, which are in short supply because LINK is simply too new of a service. This kind of lack of reliable – let alone actionable – revenue information is something that clouds the entire streaming landscape.

Even the royalty reports and analytics that artists and labels receive can be problematic. When a piece of music is being streamed on dozens of different platforms in countries around the globe (many of which have their own, unique laws regarding streaming), the data created can be overwhelming. Reports and analytics vary wildly from platform to platform, so artists and labels are frequently left with a series of seemingly endless spreadsheets. Faced with row after row of numbers, many of them detailing miniscule sums of money, it can be challenging for artists and labels to decipher royalty reports, let alone verify their accuracy.

“I would like to think they’re pretty accurate,” says Hyperdub’s Jones. “It’s certainly difficult to say how accurate they are due to how many sources are involved in procuring the vast amount of data... [but] my big issue with digital sales and streaming data is the speed in which the label receives it from the distributors. It can take anything from three to six months to know how well a release has done.”

If you consider the fact that industry-wide metadata issues and shortcomings (which anyone who’s received a promotional download already knows are highly prevalent in electronic music) have led to billions in unclaimed and unpaid streaming royalties, the complete revenue picture becomes even fuzzier.

FRESH APPROACH

Artists and labels looking for more transparency might be encouraged by what’s happening with Resonate, an organisation which bills itself as “the ethical streaming co-op”. Organised as a co-operative and built on blockchain technology, its annual profits (which at this point are still theoretical) will be split between artists (45%), listeners (35%), and staff (20%). By utilising blockchain, Resonate can prioritise user privacy and more accurately track streams, ensuring that the rights holders are paid correctly.

They’ve also taken a creative approach toward pricing, offering a model called stream2own. Rather than charging a fixed monthly subscription fee, users are instead charged based on what they actually listen to. The first listen to a song costs $.002, and doubles with each subsequent listen. Resonate keeps 30% of the revenue from each play, but after 9 listens (which add up to a little more than $1 total), the user owns the track, which can then either be downloaded or streamed endlessly at no additional cost. It’s an elegant approach that consumers who still value owning music will appreciate, and it ensures that artists are not just paid for every stream, but are paid more fairly.

At first glance, Resonate appears to be both more beneficial to artists and more innovative than many of its competitors, yet it’s worth noting that the platform has yet to prove itself. Although artists and labels are free to join Resonate and directly place their music on the site, as of May 2019, only 4700 artists/bands and 770 labels had signed up. More concerning was the fact that the total number of listeners at that point was only 3600. Resonate also did a “brand relaunch” earlier this year, following serious operational and financial difficulties stemming from the fact that a significant portion of its funding was tied to volatile cryptocurrency.

Time will tell if Resonate can navigate these challenges, but the organisation’s desire to implement an “ethical” approach is certainly encouraging amidst a nebulous and often discouraging streaming landscape. It’s a world in which uncertainty abounds, and even the industry’s biggest players have trouble making predictions about where things are headed.

For now, however, these platforms are largely operating as volume enterprises, and the needs of niche, underground music scenes are often low on their priority lists. Facing this challenge, much of the music community is left with only one sensible option: get informed, get organised, and proceed with caution. Streaming isn’t going anywhere, but if artists and labels work together toward building something better, perhaps they can avoid getting swept away in the current.