How T2’s ‘Heartbroken’ brought bassline to new heights

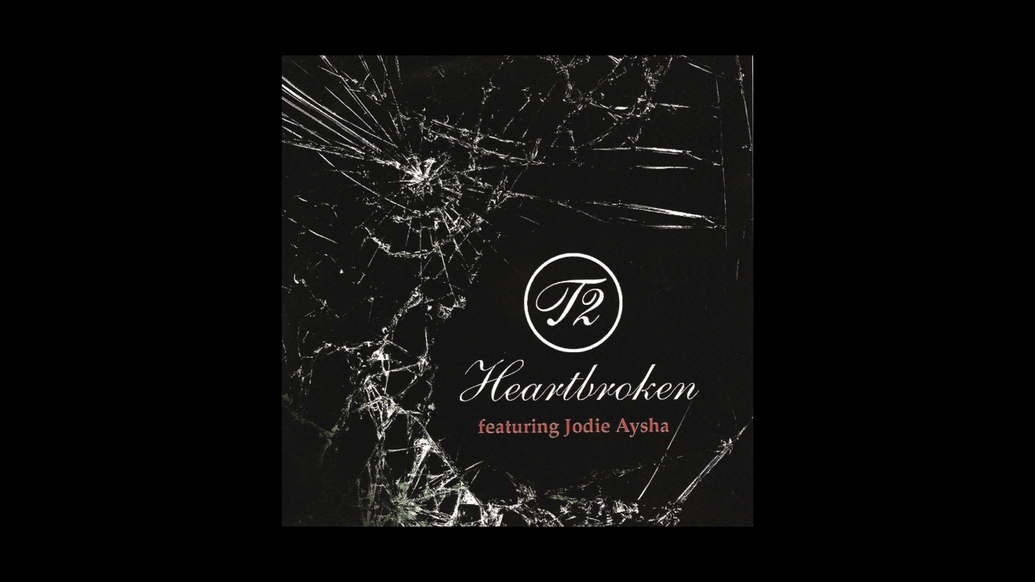

T2 was only 18 when he dropped ‘Heartbroken’: a sweet, infectious bassline tune that rocketed to No. 2 in the charts in 2007. Owing as much to grime and UKG as it did to the Niche bassline style, ‘Heartbroken’ changed the Leeds-born producer’s life, and the scene at large. Matt Anniss hears its story

In early 2007, far away from the gaze of the London-based music media, a song by a cult local producer began to spread like wildfire within the working-class communities of Yorkshire and the Midlands. Passed between mobile phones via Bluetooth, the song could soon be heard on the top deck of buses, on street corners, and blasting out of the booming stereos of passing cars.

This was ‘Heartbroken’, a hooky, energetic and life-affirming track that paired bouncy synth-string stabs and R&B-style vocals with the distinctive warped bass and shuffling, 4/4 beats of speed garage. By the end of the year, it was riding high in the UK singles chart, introducing the world to a style of music that had all but been ignored outside of the sizeable, close-knit scene built around it: bassline.

“I remember that track taking off — every time it was played, dancefloors went crazy,” says Haider Masroor, now an established producer with releases on Aus and Warehouse Music, but back then an aspiring bassline DJ and producer under the DS1 alias. “Guys were running up to the decks and demanding rewinds. It still goes off anywhere you play it now. I could drop it at 6am in Panorama bar and people would be skanking out to it.”

To some, the song’s runaway success was a surprise, despite its accessibility, infectiousness and singalong-friendly chorus, but it didn’t just appear out of the blue. Its creator, a then 18-year-old from the deprived Harehills neighbourhood in Leeds who went by the name T2, was a rising star within the bassline scene. Furthermore, he had earned a reputation for creating killer cuts that took the sound in thrilling new directions.

Bassline as a style was firmly established as a thriving regional scene by the time that ‘Heartbroken’ started spreading, virus-like, between mobile phones. Over a number of years in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the sound developed organically at the celebrated (and now notorious) Niche nightclub on Sidney Street in Sheffield. During this period, the venue’s resident DJs — Jamie Duggan, Shaun ‘Banger’ Scott, Nev Wright, Andy Spoof and Chris Bailey — were responsible for shaping “the Niche sound”, a mutant, pitched-up hybrid of speed garage, glossy soulful house and R&B that prioritised warped, mind-altering basslines, skipping drums, and celebratory dancefloor energy.

Later renamed bassline, it was a sound that struck a chord with clubbers from working-class communities up and down the M1. It was these dancers who helped popularise the music championed at Niche, Boilerhouse in Bradford, Casa Loco in Leeds and the Heaven & Hell parties in the Midlands, first by swapping tapes and mix CDs recorded by leading bassline DJs, and later via tracks pinged between mobile phones.

As a result, bassline was embedded within the culture of the communities it emerged from in a way that many other styles of British dance music simply aren’t. “The reality is that bassline was ghetto music,” Sheffield-born Haider Masroor says. “We’re all guys and gals from the ghetto. This was our music, our thing.”

BASSLINE

One thing that dramatically helped raise the style’s profile was the presence on BBC Radio 1Xtra of a true bassline champion, Huddersfield’s DJ Q. When the station awarded him a residency in 2004, he took the opportunity to promote the sound to a national audience for the very first time. DJ Q would remain a pivotal figure as bassline reached its commercial zenith between 2007 and 2009.

“In the North and Midlands, bassline was the popular thing for anyone between the ages of 16 and 40,” he says. “In the clubs, it was Black, white and Asian people all together. There was a wide age range, and people from different backgrounds, just as it should be.”

It was into this thriving, if largely overlooked, scene that T2, real name Tafazwa Tawonezvi, emerged in the mid 2000s. His ascent ended up being extremely rapid, but it was built on years of graft. He first started making hip-hop and R&B beats as a 13-year-old, initially at friends’ home studios and later in his bedroom using a combination of demo software and Fruity Loops.

“At first I was just making music for my mates to hear, then I joined a little crew when I was 15,” T2 explains. “That’s when we started making original tracks. When I was 16, we made a hip-hop CD and put it in shops and stuff. We had an idea to make our own grime beats, rather than buying them in from southern producers. I think that’s what initially helped me blow up, because I made 70% of the music on the weekly CDs that everyone was MCing over. My name began to get about because my work rate was unmatched.”

Although focused on hip-hop and grime, T2 also occasionally dabbled in bassline, though until early 2006 these productions had not left his bedroom. “You’ve got to remember that bassline was part of the culture up North,” he says. “When I started going to raves when I was 15, I’d hear beats in there that I thought were sick, and that everyone was vibing to. But I felt like I could bring something different to the table. I was kind of right about that.”

Confident about the quality of the bassline productions he was making, T2 decided to pass some onto a friend, who in turn shared them with others via his mobile phone. “Before I knew it, everyone had them on their phones,” he says. “Initially I was livid about it, but afterwards I saw it was a good marketing tool. Sometimes I’d specifically make music to pass around, just to build my name up.”

A CD containing one of those tunes, ‘Saving All My Love’, made its way into the hands of Niche residents Shaun ‘Banger’ Scott and Jamie Duggan, and later DJ Q. All three championed the track in their sets, and suddenly T2 was one of the most talked- about young producers in bassline. “I remember the first time I heard ‘Saving All My Love’ at Niche at the Limit in Sheffield,” Haider Masroor says. “It was literally a vocal for 16 bars, then without any cues it dropped straight into the beats and bass. No messing, just straight in!”

“The whole thing happened really quickly — I think it only took around 30 minutes. How you hear the extended version is pretty much how I built it in real time” — T2

MOBILE PHONES

Throughout 2006, T2 kept circulating productions to the DJs that mattered while also allowing tunes to go viral via mobile phones. His music stood out from the crowd because it was different: a subtle mutation that appealed to a new generation of bassline clubbers who were equally as interested in grime and dubstep.

“Whereas the previous bassline tunes that were big in the scene were quite polished and took cues from house, garage and speed garage, T2 was taking more cues from grime,” Masroor says. “There was a guy from Leicester called Zibba who started doing that a little earlier, but T2 blew the doors down. All the basses that he used were completely different — the pitch and sound was really mutated and gnarly. If you took out the four-four drums from those tracks, they’d be between grime and dubstep.”

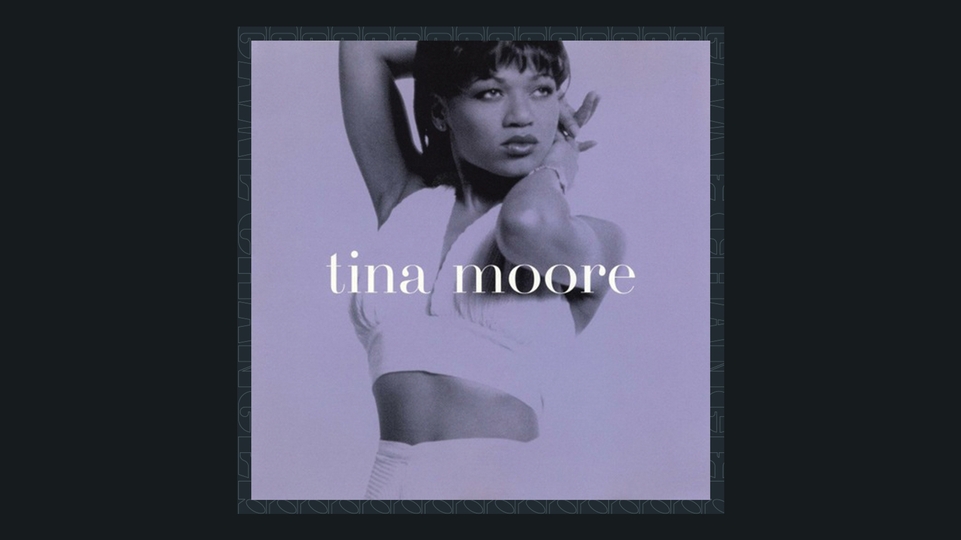

Some of these ground-breaking sonic traits would end up in ‘Heartbroken’, but by and large that track was far softer, slicker and more soulful than many of T2’s productions. He’d started working on the song a few years earlier with its vocalist and co-writer, fellow Harehills teenager Jody Aysha. They were planning to craft an R&B song, but it was never finished; instead, Aysha’s vocal recording sat unused on T2’s hard-drive for a number of years.

As 2006 turned to 2007, T2 was riding high musically, but had a court case looming that could have seen him spend “a hefty amount of time” in prison if found guilty. The night before he was due in court, he decided to turn on his laptop and try and make a bassline banger using Aysha’s vocal. “I thought the vocal was decent and I could do something with it,” he remembers. “So, I took it out of the unfinished R&B version and then started making a bassline beat around it. On most of the tracks I made, I played keys and stuff, but on ‘Heartbroken’ I made everything in the computer. It was a different approach for me and the whole thing happened really quickly — I think it only took around 30 minutes. How you hear the extended version is pretty much how I built it in real time.”

He played it “around a hundred times” and then fell asleep. The next day, he was acquitted in court, returned home and emailed the bassline version of ‘Heartbroken’ to Shaun ‘Banger’ Scott, who put it on his January 2007 mix. “A few days later, I got a call from one of my mates,” T2 says. “She was like, ‘This track that you put out the other day... I can’t stop playing it!’ That was a day after it appeared on Shaun’s mix. A couple of days later I went to Sheridan’s in Dewsbury and people were walking up to me and saying, ‘All the girls from my town won’t stop playing ‘Heartbroken’!’ From that point on it was just an upwards trajectory.”

DJ Q quickly gave the song its first airing on 1Xtra. From the start, he could see that it was both special and significant. “Out of that new generation of bassline producers, it was the first big, original vocal track,” he says. “Early in the scene, most bassline tunes were bootleg remixes, so the only way labels could release them was if they got the vocals re-sung. ‘Heartbroken’ wasn’t like that because it was totally original. It was big from the start and just got bigger over time.”

DJ Q points out that by this point in 2007, bassline was no longer the niche regional scene it once was: as the style’s best-known DJ, he was playing regularly all over the UK. In fact, the only place bassline had not made a significant impact was London, despite the city’s UK garage heritage. ‘Heartbroken’ changed all that, becoming just as big in London as it was elsewhere in England and Wales.

“It came out on vinyl at the start of the summer through a distributor in London, which meant it was going to all of the London shops as well as the ones up North,” DJ Q says. “The label that licensed it from T2, Around The World, also promo’d it to DJs who would not normally have got bassline tunes. So, when the summer holiday season in places like Ayia Napa came around, all the DJs had it and could play it when requested. Then people from outside our scene heard it and it became a huge hit.”

INFLUENCE

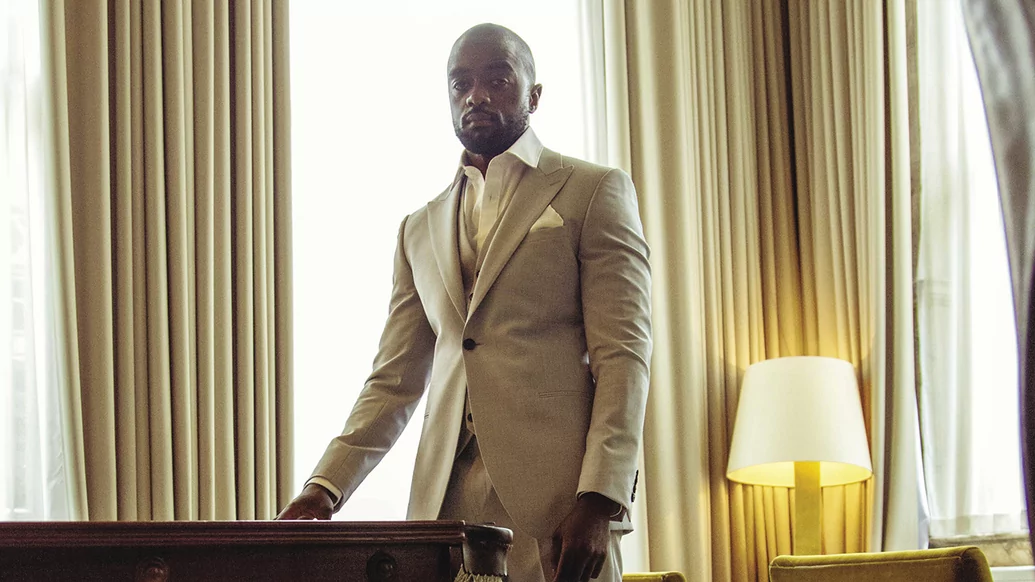

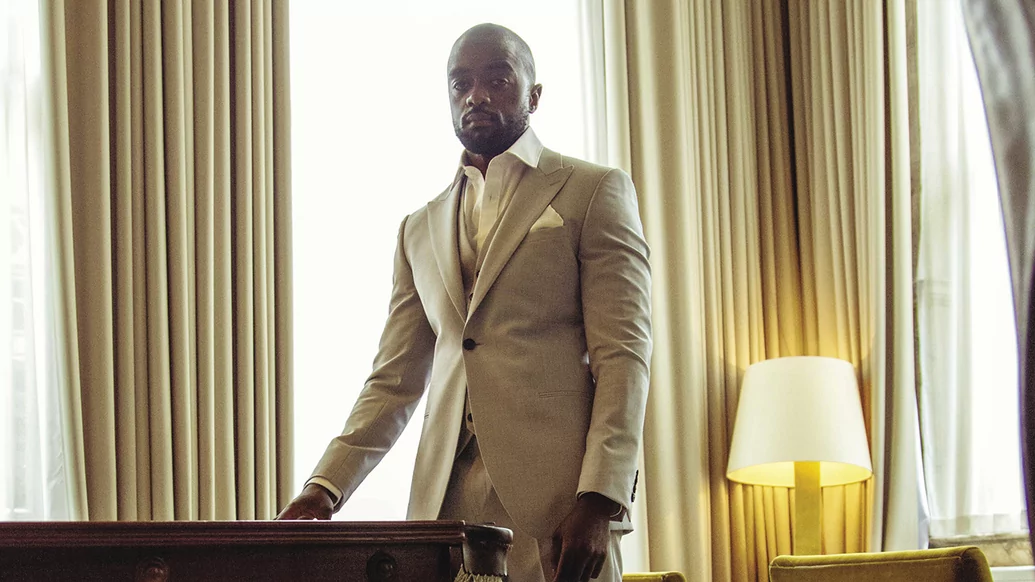

Promoted via a video that showed T2 hanging out at the headquarters of his management company with some of the professional footballers they also represented — Micah Richards and Anton Ferdinand included — the single rocketed to number two in the singles charts, reportedly selling over 300,000 copies just in 2007 alone (it has since gone on to rack up many millions of streams and still sells in significant numbers).

“‘Heartbroken’ is a stone-cold classic that transcends genre,” says Tom Lea, the Hackney-born founder of Local Action, a label that has released numerous bassline cuts since it launched a decade ago. “It’s a UK classic in the same way that ‘Flowers’ [by Sweet Female Attitude] or [So Solid Crew’s] ’21 Seconds’ are. I also love how its influence has spread beyond the UK — it has taken on its own life across the pond through DJ Jayhood’s Jersey Club version. There’s something so gratifying about the way that music can take on its own life in different countries and cities.”

The runaway success of ‘Heartbroken’ had a profound impact on T2’s life. Less than 12 months after making the track in the early hours of the morning in his Harehills home, the producer had become one of the hottest names in UK dance music. Labels scrambled to sign T2’s tunes and the pressure to create another chart smash was immense. As you might expect, the then 19-year-old struggled to come to terms with his new-found fame.

“It was too much — I wasn’t ready,” he now admits. “When you’re catapulted into a crazy place that you’re not mentally, physically and emotionally prepared for, it’s going to throw you off your square a little bit and you’re not going to make the best decisions for yourself and your career. I thought it was going to be a longer process, but a year after making my first bassline tunes my whole life had changed. It’s hard to adjust to something that’s already happened.”

Having stepped out of the limelight in 2010, T2 took some time out to work on his production skills (“There’s levels of being a producer,” he says, “and I wasn’t at the level I wanted to be at”), before pursuing a secret career in house music under an alternative alias, Marc Talein.

Over the last four years, T2 has periodically returned to bassline on his own terms, first with 2016’s ‘Return Of The Grandmaster’ EP, and later via 2018’s mixed collection of his soundsystem-slaying productions, ‘Bassline Classics’. Now he’s all set to release “something special for the fans” this year, though he’s keeping tight-lipped about exactly what in order to keep it a surprise.

As for the legacy of his most famous record, it marked a watershed moment in the history of bassline, effectively embedding the sound in the national consciousness. “It was a gift and a curse,” DJ Q says. “After it got to number two in the charts every label was looking for the next bassline hit. The sound changed, because people saw the success of it and softened their style to fit what they thought labels wanted to hear. But there were other songs that got signed on the back of it and did all right, so it was a gift as well as a curse.”