Pressing issues: is this the end of the vinyl revival?

Manufacturing delays and rising costs are straining small, independent vinyl labels. Paired with environmental concerns and a reassessment of what physical releases can entail, the wax bubble appears to be bursting. Is this the end of the vinyl revival? Will Pritchard investigates

The word “shitshow” comes up a lot when you talk to independent label owners about producing vinyl. Emily Moxon, managing director at Brownswood, says that venting about the process is “like therapy”. When asked about the pains and pleasures of making records, one simply responds: “There are no pleasures”. John Also Bennett, who works as production manager at RVNG Intl., puts it more delicately. “With producing vinyl, patience has always been a virtue,” he says, “but now this virtue has reached an extreme.”

Pressing and selling vinyl has long been a labour of love for small labels. But a growing number of factors is making it harder than ever to justify the pains. The price of PVC, the raw material used to make the records, has shot up by more than 46% since the beginning of this year, after Winter Storm Uri struck Texas and froze out the state’s petrochemical plants.

Cardboard used for record sleeves and shipping boxes is thin on the ground, swallowed up by e-commerce giants to meet the past year’s sky- high demands. A devastating blaze at Apollo/Transco in February 2020 reduced the number of lacquer plate producers in the world to just one — MDC in Japan. The result is stretched lead times, leaving labels out of pocket for longer.

Postage fees are on the up too. The cost of sending records overseas from the UK has increased by around a third since last year; and as of July 2021, items imported to the EU with a value of €22 or less have lost their VAT exemption — adding a further, costly headache. Brexit hasn’t helped, particularly when it comes to records crossing borders; DIY labels and distributors have had to navigate a whole new code of customs nomenclature.

On top of this, Covid-19 created a slingshot effect on the already-brittle supply chain. Labels hit the brakes when the virus first arrived, before scrambling to meet demand from an audience sat at home with money to burn and a heightened awareness of the plight of artists, thanks to initiatives like Bandcamp Day.

Europe’s pressing plants have been unable to absorb the increased demand. Plants trying to order new machines have been hindered by issues further up the supply chain, as parts and completed units aren’t being delivered to factory floors in time to provide extra capacity. Social distancing and the need for workers to self-isolate has caused labour shortages.

But as with lots of things — screen time, online shopping, the desire among billionaires to use their personal wealth to escape the earth in private rocket ships — Covid-19 has merely accelerated an existing trend. In truth, the squeeze for small labels was well underway before the pandemic. The storm was perfect already, Covid-19 just made it rain harder.

"I don't think that an artist should have to press vinyl for one release to be taken more seriously than others... That creates an uncomfortable dynamic, financially and environmentally” - Tom Lea, Local Action

According to the British Phonographic Industry, demand for vinyl has been growing since the format’s 2007 nadir. Turntable sales figures are also a strong metric for tracking demand, as they provide a picture of how many new or returning enthusiasts may be joining the fray. In 2017, record players comfortably outsold speaker docks and headphones at HMV to become the top-selling technology product during the winter shopping period. John Lewis reported a 20% increase in sales of high-end turntable models in the same year.

Karen Emanuel, CEO of broker-manufacturers Key Production, says that demand today is similar to the ’90s, when she founded Key. The crucial difference is that the enormous, major label-owned pressing plants like EMI in Hayes and CBS in Aylesbury are no longer around to service that demand. One significant outcome of this squeeze is that wait times for smaller labels are stretching from weeks into months and years.

Jeremy Pattison has run Innamind Recordings for a decade. He’s seen turnaround times go from four weeks to complete the whole process, to six weeks to receive a first test pressing. John Also Bennett at RVNG Intl. says that one plant he works with in the United States informed him they had “500,000 records to press before they could even accept a repress order”. Small labels are facing minimum turnaround times of six months or more. Some report waiting over a year between placing an order and seeing any records.

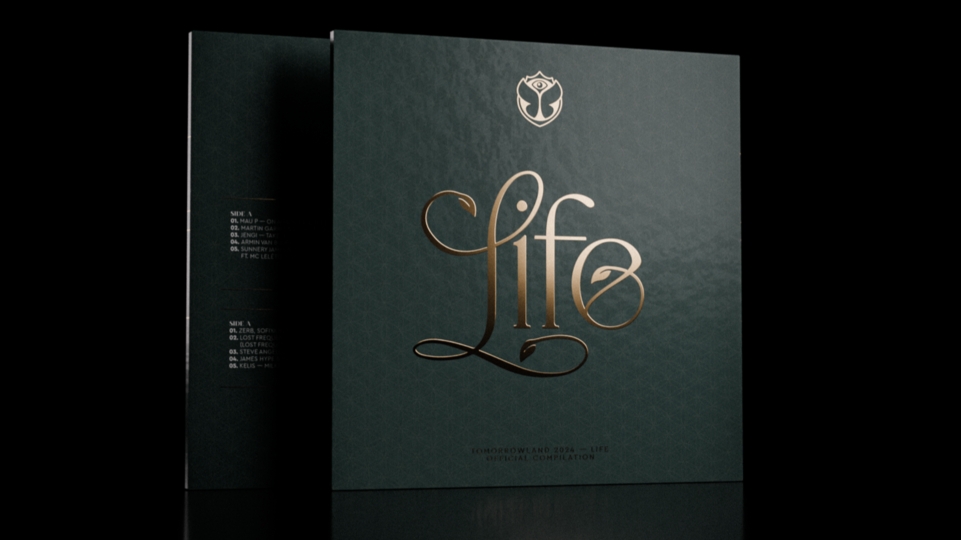

One explanation for these backlogs that is anecdotally rife, but harder to prove, is that pressing plants’ capacities are being bunged up by major labels ordering deluxe represses and collectors’ editions of albums from their extensive — and lucrative — back-catalogues.

New releases have been getting the vinyl treatment too, and albums sold as part of expensive merch bundles have become a fixture in the pop charts. “Because we’re not getting 500 made or 1,000 made, we don’t get prioritised in the same way,” says Lois Browne, production manager at boutique label SA Recordings. “But that kind of sucks, because even though we’re doing small runs, that doesn’t mean to say we’re less important.”

Karen Emanuel says that the reality of the situation can be misconstrued. She says that major labels operate similarly to brokers, or contract out to brokers (indeed, Key has worked on a number of big projects for the majors). Pressing plants provide an allotted capacity, and then it’s up to the label or broker to consider how best to use this capacity to get the orders they want completed. Emanuel says that brokers who work with both small independents and bigger clients are using their position and their long-term relationships with the pressing plants to spread capacity around. In some cases, this involves placing caps on the number of orders major labels can place.

But the truth of the situation is muddied by a former employee of one of Europe’s big pressing plants, who tells us that majors are frequently able to jump the queue, and that brokers are often happy to simply take the biggest payday available to them. “There’s no thinking about the long term,” they say, “they just assume we’ll only be pressing Rolling Stones represses, and the indie labels will somehow magically reappear when people don’t need Rolling Stones represses anymore.”

For independent dance music labels — who maintained their loyalty to the format during the doldrum years, around the turn of the millennium — this stings. And beyond the boring business minutiae of running a label, these issues are having a considerable cultural knock-on effect too, as the mechanics of the industry fail to keep pace with the evolution of underground scenes.

“It basically means the whole release schedule is going to be so out of sync with what people are making,” says Facta, who, along with K-LONE, runs vinyl-first label Wisdom Teeth. “If a new sound pops up now, it might be a year before we see any records from it. We’ve signed some amapiano tracks; it would have been amazing to get those out this summer, as it’s bubbling and there are parties for it, but those probably won’t be out until next summer now.”

Scuba has been pressing records through his Hotflush imprint for nearly 20 years. Having witnessed the influence of dubplate culture on sounds ranging from jungle to dubstep, garage and grime, he’s acutely aware of the cultural ripples that have, in the past, pooled out from these plastic discs.

“It’s not just vinyl, but the record shops and everything that goes along with them — their significance as important spaces in the incubation of music scenes.” New music scenes, it’s fair to say, aren’t incubating in Sainsbury’s and Urban Outfitters.

“There’s still definitely a subset of people who think that if a release doesn’t come out on vinyl, then it’s not really a release, but I think that subset of people is shrinking” - Scuba, Hotflush

Slim margins, stretched turnarounds and serious environmental concerns about committing music to plastic discs — metaphors don’t come more direct than reports that this summer’s extreme heatwaves in the USA caused vinyl shipments to warp en route to customers — are forcing small labels to reassess their relationship with vinyl. This also means reconsidering the format’s cultural heft.

Since the mid-’00s, the cost and hassle of pressing records has given vinyl an implied higher status. Songs cut to wax, the prevailing wisdom goes, are to be taken more seriously. But this attitude appears to be shifting. “There’s still definitely a subset of people who think that if a release doesn’t come out on vinyl, then it’s not really a release, but I think that subset of people is shrinking,” says Scuba. Labels are beginning to shake off the expectation that they should be producing vinyl to be taken seriously. “A massive change in how I’ve run this label is to stop building our release campaigns around vinyl dates, and not to worry if vinyl trails digital,” says Tom Lea, who’s been running Local Action since 2010.

For Lea, it’s not just about costs and lead times. He expresses discomfort at the idea that a piece of music pressed to vinyl should be considered “more important” than one that isn’t. “I don’t think that an artist should have to press vinyl for one release to be taken more seriously than others,” he says. “That creates an uncomfortable dynamic, financially and environmentally.”

Many label owners, Lea included, say they’ve begun thinking of vinyl records as merchandise, as opposed to a listening format first and foremost. “I think it’s at a point now where, for environmental reasons and because of manufacturing issues, people are having to make a lot more critical decisions, like, ‘does this need to be pressed to wax?’” says Josh Byrne, who runs XVI Records and its High Praise Edits offshoot. (One thing vinyl is still good for is putting out tracks with “cheeky” samples.) “If vinyl is just merch, then maybe you just do other, more creative merch ideas?” he wonders aloud.

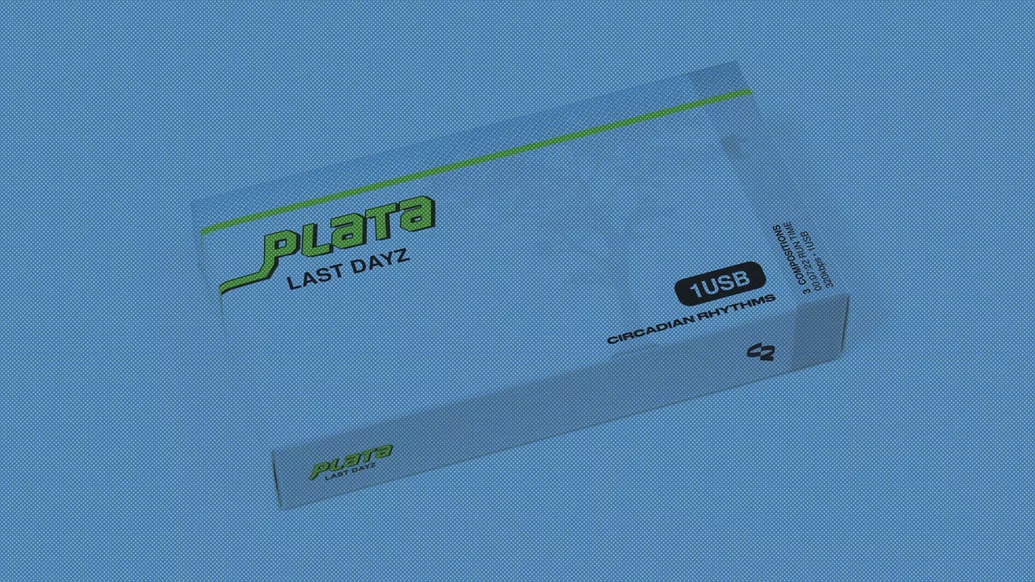

Circadian Rhythms, a multidisciplinary label and UK collective, has been experimenting along these lines since the late 2010s. Recently, the label has produced USB cards, booklets, cassettes, and a hand-stitched military sewing kit made from reclaimed materials. They’ve also launched a free repair service, taking inspiration from ethically conscious brands like Patagonia in its efforts to better reflect its values through its work. This has allowed the collective to embrace and expand on more conceptual release formats.

Plata’s 2018 USB release, ‘Last Dayz’, was presented in mock pharmaceutical packaging to reflect the EP’s exploration of mental illness and modern medicine. An online scavenger hunt unveiled more music, and posed questions about the intersection of our digital and physical realities.

“As a label, we’ve understood that there’s so many other interesting ways to explore physical releases, so why limit yourself necessarily to a 12-inch plastic disc just because that’s what people collect?” says William Green, one of the collective’s members. Green is open about his love of vinyl records, and still collects them himself. He talks at length about their tactility, admiring the blown-up artwork and examining each track by its groove in the PVC. But he can’t see a sustainable future in the format. “The reason people are interested in vinyl records is because they’re becoming the artefacts of the releases that they cherish, rather than being those releases themselves,” he says.

Ultimately, labels are balancing competing interests. On the one hand, they exist to help artists realise their creative visions, and earn a living from them. But they’re also tasked with leaving marks in history, and guiding the future understanding of scenes. Recent years have brought a changing understanding of the lifespan of digital artefacts. The assumption that once something is shared online it’s there forever is increasingly being undermined. Browne, from SA Recordings, jokes that she justifies her personal vinyl expenditure by imagining a dystopian near-future in which the world’s computer systems fail and the earth’s population, having become so dependent on digital delivery, is left without access to music. Except for her, of course: she’s able to continue listening to her favourite records, unfettered by such technological concerns.

As exaggerated as Browne’s justifications are, you don’t have to look far to find countless examples of the true ephemeral nature of the web. MySpace’s loss of 50 million songs in 2019, in what the company characterised as a botched server migration, is just one high-profile example.

Organisations like the Internet Archive and the Great 78 Project can only cover so much ground, and will inevitably have blind spots — which raises significant questions about how music scenes can be documented in an increasingly digitised world.

When Karen Emanuel cut the ribbon on Key Production in 1993, people told her “that vinyl was going to disappear within five years”. Evidently it hasn’t. But supplies are running thin. And the patience of indie label owners is too.