The renegade soundsystems of California that shaped West Coast rave culture

California's rave history is rooted in outdoor free parties that celebrated psychedelic music and and unique environments. DJ Mag's Matt Anniss speaks to the Bay Area DJs and soundsystem crews who started it all, and shaped how contemporary West Coast artists get down today

Every summer since 2005, Claude VonStroke’s DirtyBird crew has hosted a “BBQ” party in one of San Francisco’s many harbour–side parks. They’re not alone, either, with numerous licensed and unlicensed outdoor events taking place along California’s West Coast all year round. It’s a tradition that traces its roots back to the early ’90s, when enthusiastic locals and acid house-loving British immigrants threw parties that brought a taste of UK rave culture to San Francisco and Los Angeles.

By the turn of the decade, San Francisco was in a state of flux. The technology boom that’s reinvigorated the city in recent decades had yet to begin, and the powerful October 1989 earthquake had caused over $5 billion of damage to local infrastructure. Yet the Bay Area’s alternative music culture remained vibrant, with strong scenes for psychedelic rock, punk, industrial and new wave. The only aspect of the city’s musical culture in need of fresh impetus was the club scene.

Enter Garth Wynne–Jones, an idealistic young British backpacker who arrived in San Francisco after experiencing the birth of Britain’s rave revolution. He’d been turned on to acid house by the maverick party collective Tonka Sound System, known for their monthly residency at the Zap club in Brighton and weekend–long parties in the Cambridgeshire countryside, joining the dots between rave, disco, psychedelic rock and Balearic pop. It was this loose and loved–up style that Wynne–Jones wanted to bring to what he says is “the most psychedelic city in America.”

Though San Francisco had yet to embrace acid house, there were a handful of DJs attempting to further the cause. “Ernie Munson had an amazing collection of house records but was frustrated that nobody seemed interested,” Wynne–Jones remembers. “We bonded right away. I went to the DNA Lounge to hear Doc Martin play in 1989. He would play hip–hop tracks and some dance stuff, with the occasional house track near the end.”

When Wynne–Jones returned to the Bay Area one year later to set up home, things were slowly changing. San Francisco gay clubs Osmosis and Collossus had embraced house and techno, and a vibrant renegade scene was taking shape in Los Angeles. In 1988, Latino teenagers hosted afternoon dances in suburban homes known as “ditch parties.” By 1990, some of those teens had graduated to throwing bigger events in warehouses and former factories. One of the DJs in this burgeoning Los Angeles scene was Doc Martin, who was now playing breakbeat–driven European hardcore, slamming techno and mind–altering acid house. It was tough, rough and raw: over the years to come, the Los Angeles’ scene would only get more wild and intense.

In San Francisco, Wynne–Jones was DJing as DJ Garth and selling homemade acid house mixtapes. He invited over some of the UK crew he’d met at Tonka events and, to his delight, they all decided to stay. DJs Thomas Bullock (Tom of England), Markie (known for his Tonka after-party sets on Brighton beach) and Jeno (a member of anarchist London squat party Whoosh) wanted to replicate the outdoor raves they’d enjoyed in England on America’s West Coast.

“It was a full moon,” Wynne–Jones remembers. “Munsen said to us, ‘I know this incredible beach called Baker Beach and a soundsystem company’.” Wynne–Jones had not visited Baker Beach, but was aware that it had played host to a few crazy gatherings known as Burning Man. By the time they’d soundsystem down there in 1991 Burning Man’s founders had departed for the Nevada desert. It was a fitting place for the Wicked Sound System story to begin. “We had this incredible party with 40 or 50 of us, mainly friends from the gay scene,” Wynne–Jones remembers. “We hadn’t noticed where we were, so when it began to get light and the fog rolled back, we were shocked to see the Golden Gate Bridge above us. It lit up like a spaceship.”

Over the next six years, Wicked Sound System held outdoor parties every full moon. Constantly moving location to avoid the police, they popped up at “every beach and deserted farm” around the Bay Area. “We had different styles that came together to form the Wicked sound,” Wynne–Jones says. “Markie was really deep and fluid, with lots of New York disco and deep house. Thomas was funky, leftfield and Balearic. Jeno would take you on a shamanic journey with deep acid. It took me a few months to hone my sound, but I was inspired by those three.”

“At one point, we took our soundsystem and set up in the car park outside a Grateful Dead gig. Those old hippies who followed the band around got what we were doing.”

Through word of mouth, Wicked’s full moon parties became must–attend events. One rave at Bonny Dunes near Santa Cruz attracted over 3,000 dancers. They appealed to rave kids and house heads, but also old hippies and survivors of the city’s Grateful Dead–inspired “deadhead” scene. “We made an effort to reach out to the deadheads by handing out fliers at their get–togethers,” Wynne–Jones remembers. “We took our soundsystem and set up in the car park outside a Grateful Dead gig. The hippies who followed the band around got what we were doing.”

One DJ who found Wicked inspirational was Solar Langevin. “I was totally hooked on and a bit star struck with the crew,” he admits. “I was blown away by that DIY style of just taking the clubbing experience outside to these stunning locations. The music also seemed a bit freer and more eclectic when they were outside, certainly compared to the acid house nights they were running simultaneously in warehouses and clubs.”

By 1993, Wicked’s efforts were being replicated further South in the vast deserts outside Los Angeles. The Moontribe Collective – a free party dedicated to “shamanistic techno and house” – had begun hosting all–night or weekend–long monthly full moon parties in dusty, alien locations. Their sound was more forthright in keeping with the LA scene in general – tougher, heavier beats, prioritizing intensity over groove – but similarly trippy in ethos.

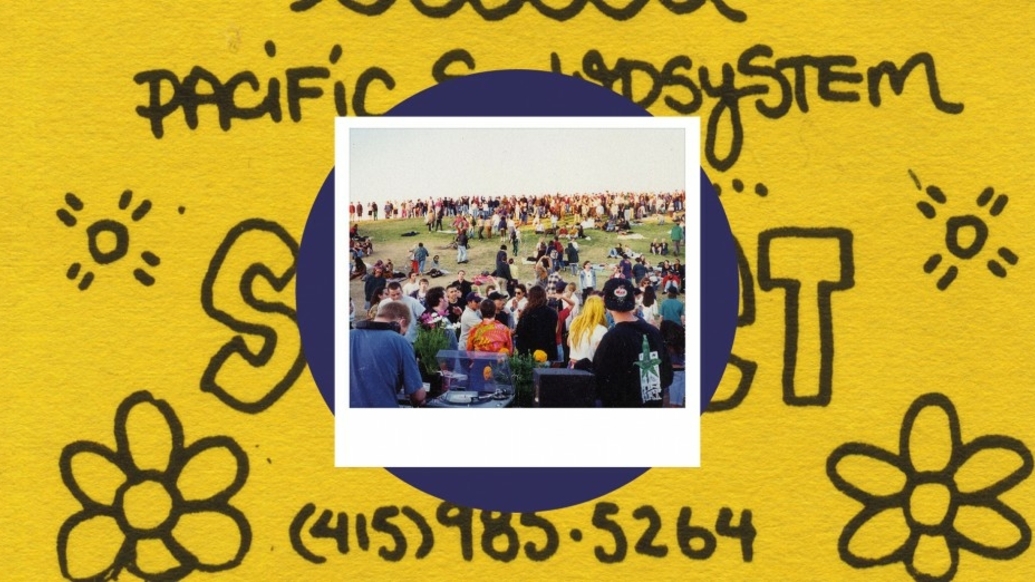

Free or donation–based illegal outdoor events were becoming popular across the Bay Area, too. On the Spring Equinox in March 1994, former wannabe Olympic swimmer and acid house convert Galen Abbott threw his first unlicensed outdoor event, a Sunday afternoon affair at Berkeley Marina. He’d been introduced to indoor raves a year earlier, and his obsession had grown after he’d attended Wicked’s full moon parties.

“I’d already maxed out credit cards to buy a DJ set–up and had just got a line of credit to buy a soundsystem,” Abbott remembers. “My friend J–Bird had access to a generator and I’d met Solar at a house party. Another friend was good with electronics and my roommate had a truck. We pieced together this crew and started promoting parties through word of mouth, with hand–drawn fliers.” These parties would become known as the weekly Sunday afternoon Sunset Sound System events. “There were only about 10 people there [at the start] but we kept going. By late 1994, I was freaking out about there being 1,000 people there.”

After switching from Berkeley Marina after a couple of years – locals had called the police about a lone naked raver, high on acid – Sunset moved to Point Molate, a park under the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge. “The park was in bad shape, so we cleaned up a bunch of trash before and after the event,” Solar Langevin says. “The local police chief saw the effort everyone had made... He gave us his card and said that if any other police came to harass us, [we were] to give him a call and he would make sure they didn’t shut us down. We lasted there for four years.”

Musically, Sunset was different from Wicked, but like the former, the latter prioritized vibe over musical definitions. “We’d start with funk, soul, disco, rock, reggae and dub, and later in the afternoon these records would be woven in with the deeper house, acid breakbeats and techno,” Abbott says. Sunset proved more accessible than Wicked’s all–night affairs, tapping into Californians’ love of sunshine. “They were lovely daytime picnics and everybody would go because it was a leisurely affair,” Wynne–Jones says. “The fact that they’re still here doing their thing 25 years later is great.”

As the ’90s progressed, Wicked’s full moon parties became less frequent. Instead, they loaded their 15k custom–built Turbousound system into the back of a 1947 Grayhound bus and set off on tour across the south and mid–west. They were in–demand DJs, having inspired what would become known as the “West Coast” sound – deep and dubby psychedelic house music that mixed acid house culture with the longstanding counter–cultural ethos of California’s hippie heritage.

“We still see people at our events who have been coming down since the early days. In some cases we see their sons and daughters as well.”

This sound reached its peak of popularity in the early ’00s, with a host of West Coast record labels offering their own twist on the sound. Wynne-Jones’ Grayhound Recordings led the way: for the tech–tinged deep house chug of Panhandle Recordings, the druggy hypnotism of San Diego’s Siesta Music, and the driving early morning tech–house of Tango Recordings. “I do think Wicked, Sunset and Moontribe had an effect on the music that was being made out here in the ’90s,” Abbott says. “We used to get people from lots of difference dance scenes, including drum and bass and trance, and it was really special that we were able to bring people together.”

While Wicked’s outings are now restricted to one or two anniversary club parties a year, the culture continues to be a big part of California’s dance music scene. The most high profile example of a contemporary crew tapping into this heritage is LGBTQ collective Honey Soundsystem. Although known for wild warehouse parties, they’ve thrown a number of secret sunrise parties for selected locals that join the dots: between the psychedelic eclecticism pioneered by Wicked, and the musical lineage of San Francisco’s renowned gay club scene.

DirtyBird continues to host their “BBQ” park outings and Moontribe Collective still run monthly parties in the desert, 26 years after their first event. Sunset Sound System recently celebrated its 25th birthday. They tick over with occasional park events and boat parties, and this July sees the 10th edition of their annual, weekend–long Sunset Campout, a family–friendly mini–festival in Northern California. “We still see people at our events who have been coming down since the early days,” Abbott enthuses. “In some cases, we see their sons and daughters as well... as long as we have the energy to do it and feel good, then we’ll keep going.” Wynne–Jones still DJs in his current home of Los Angeles, and takes regular trips down to San Francisco, too. “What Wicked were doing has proved to be timeless,” he says. “It makes me feel great that we helped inspire people to do events and make music.”