The return of Squarepusher

Electronic maverick Squarepusher’s new album finds him breaking his own rules, and drawing from the past for inspiration — but being him, it’s no simple nostalgia exercise. DJ Mag meets the producer in London to talk about using basic equipment, pipe organs, his rave reminiscences and the ethereal strangeness of old children’s TV theme tunes

In 1996 Dutch production company Lola Da Musica made a documentary, simply titled Drum & Bass, that has acquired cult status on the internet. Featuring an interview with Source Direct, the then just 20-year-olds are filmed driving BMWs around their native Essex.

It contains the dialogue sampled in Joy Orbison’s 2012 hit ‘Ellipsis’. More recently, LMajor’s ‘A Lesson From Rupert’, released on Club Glow, sampled the Photek interview from the same programme, the revered producer shown using rudimentary-looking software as he talks about cutting up a break. But the first footage is in the Hackney home of a youthful Tom Jenkinson, aka Squarepusher, who had just released his debut album ‘Feed Me Weird Things’. As the camera pans across bare floorboards, he sits surrounded by studio gear and records. One synth is an SH101. “An acid house mainstay,” he tells the camera. “This is the first thing I got. I saw all these sliders on it.”

He tells a story of asking the man in the shop to plug it in and hearing its possibilities for the first time. “Wow! It’s the machine,” he grins excitedly, miming fader moves and mimicking its noises as the picture fades.

Squarepusher’s music-making has always been resolutely future-facing. His last album, 2015’s ‘Damogen Furies’, was written on software he’d spent 15 years developing. But his latest, ‘Be Up A Hello’, returns to the machines he started on. First single ‘Vortrack’ gave a taste of what to expect, burbling acid and sinister pads accompanied by a blur of unpredictable drums tearing apart what he once called the “tyranny of the metre and the bar”. Yet it also came with his own ‘Fracture Remix’: a fearsome drum & bass take, the acid tuned to anthemic status; the drums straight ahead for the dance, clattering rides harking back to the darkness of early No U-Turn Records. It sounds every bit a u-turn to his own roots.

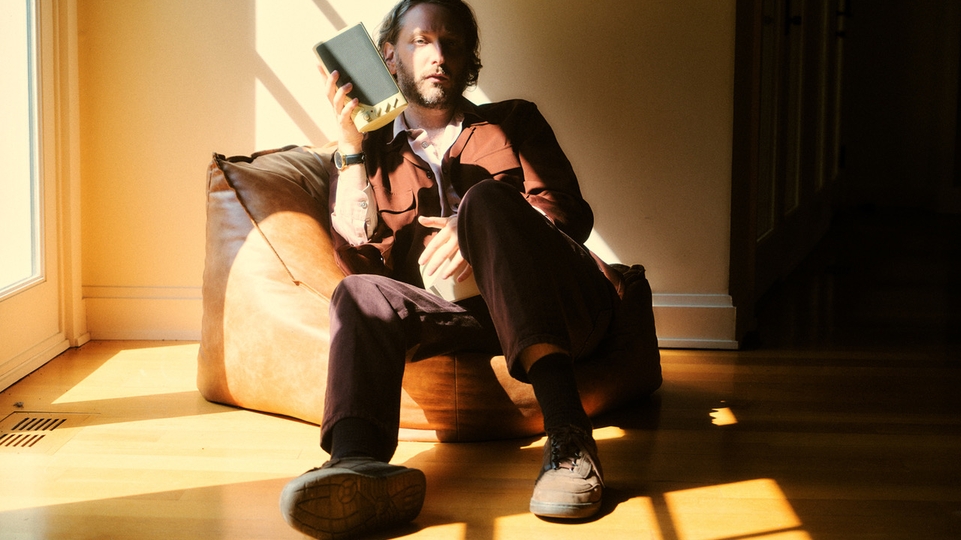

When we meet in a North London pub, his face lights up with the same flashes of enthusiasm as in that classic video, although the ’90s goatee is long gone and his grown-out hair is swept back. What he wants to make clear, straight away, is that it’s always been him that determines his sounds, not the gear he uses. He’s always tried to push the orthodoxy of what an instrument can do, be that synths and drum machines or his bass guitar.

“There might be any number of kids reading this who don’t have funds or a background of privilege that allows them to get started easily. I don’t want those people to think there are barriers,” he says, insisting that ideas come first. He cites his 2009 album ‘Solo Electric Bass 1’, a collection of bass solos, as an example of how his process can be incredibly stripped down. “Companies erect this edifice that you need this, this and this to sound great. Here’s matey boy in his studio and he looks hip and happy with his mixer.”

It’s an ethos taken to extreme levels with the album artwork and video for forthcoming live shows: they were made on the same Commodore Vic-20 he programmed to play beats to practice riffs along to as a kid in 1986, and used as a drum machine on ‘Be Up A Hello’.

MORAL OBLIGATION

In January 2018, while on a Norwegian island, Tom fell and broke his wrist. “It was a harrowing time,” he says. He damaged his scaphoid bone, which can require an operation and potentially lead to nerve damage — a huge cloud over someone who has played bass guitar since he was 11-years-old. While he’s thankfully recovered, it allowed him to indulge in his love of the feeling of a Year Zero moment, “Even if it’s an illusion, the feeling of wiping the slate clean. Looking at a box as a set of possibilities, rather than it having a sound or even a genre associated with it.”

Back at home in Essex, he dug out his old kit and set a rule of making a piece a day, then recording it. “I love crazy music, I loved music with a non-linear flow to it, but I also love house music out of Chicago in 1987 - the simple groove, the economy, the funk, the way the intensity builds up through repetition.” During this period he made what sound like straight-up house tracks, but they’re unlikely to reach fans. “I don’t believe there’s anything new in it and I don’t want to waste the public’s time,” he says when we ask why. His forte, his believes, is being idiosyncratic and innovative, and he feels a moral obligation to do this, rather than further clog up an already sentimental culture.

This process, though, led to him spending two days on a track, then abandoning any rules and developing it into the crazed opus that is ‘Be Up A Hello’, “Trying to consciously do something original”. This brings us back to his annoyance at retro culture gear fetishism: the idea that if you want the sound, you need the kit. “It turns gear into investable commodities, which takes it out of the reach of working musicians. And particularly out of the reach of people just starting out. It makes it this pointless holy grail.” Nobody can deny a 909 sounds great, he adds, but if it’s not there, it doesn’t matter.

His 909 is on every track on the record, except those without drums, but he still tried to squeeze out novel sounds: getting a liquid effect by using a midi process that sent dense streams of information to the instrument, closely packed triggers varying in velocity and frequency. “You get these big oceans of sound that pulsate. There are moments when the 909 becomes more like a synth.”

‘Be Up A Hello’ swims with these stuttering, machine gun-fired beats, among marauding acid and otherworldly melodies. It also arrives at a time when IDM has again become a buzzword. “I’ve got a deep fascination with music going out of control,” says Tom. “I love that sensation when it feels like it’s leading into unknown territory.”

The intimation of the phrase IDM is that it’s about intellect though, he says, which “is cobblers”. Intellect is just the tool, but it has to be driven by a deeply rooted desire. One of his own biggest inspirations is still Captain Beefheart’s 1969 album ‘Trout Mask Replica’. “Every time I hear it, it sounds different, and I keep wanting to return to it. At what point did the music get that property of being unknowable?”

It’s this compositional ideal he finds most compelling, a passion that means even with machines designed to stay on a grid he’s constantly looking for ways to escape it. “I have dreams about it, it’s at the core of my being.”

PURPOSE

When acid house first hit, he was at school, “Aware of the moral panic before I was aware of the music”. When it finally filtered through, it challenged his idea of what synths sounded like, acid’s lower register — borne of a machine designed to mimic a bass guitar — catching his ear.

“That throaty grit I didn’t associate with synths, which I thought were ethereal. It had so much bite and funk, I was hooked straight away.” He bought his SH-101 from Future Music in Chelmsford in April 1992 and never looked back. He’s never had to have it serviced either.

It was in Chelmsford where he first began playing live at DIY parties, such as one at the city’s football club. “I’d get my mate to DJ breakbeats and try to mix in synths over the top. As soon as I had enough kit to make a credible sound on stage, I was trying to do it.” It’s a period immortalised by tracks such as 1997’s ‘Lone Raver (Live In Chelmsford Mix)’ and ‘The Barn (303 Kebab Mix)’, named after an empty barn he and his friends went to because it would amplify the music blasting out of their car.

This spirit of early rave infuses ‘Be Up A Hello’ alongside Tom’s other biggest inspirations: jazz, Stockhausen and musique concrète. The latter has a surprising link to another of his recent projects: creating the music to the BBC’s Daydream, an hour-long programme for kids to fall asleep to that was broadcast in early 2018. It’s something he knew he had to do as soon as he heard about it, and it finds him in reflective musical form. Simple, beautiful melodies unfold to a film that’s accompanied by Olivia Coleman’s slow, steady voice, and blending with natural sounds like crashing waves or boots walking across gravel.

“Another major influence is the music on TV programmes I watched as a child,” he explains, recalling the funk of the Grange Hill theme tune as one. Rainbow, he says, had a section where it would fade to a grey screen, then a drawing would appear, line by line, with each line accompanied by an odd sound. “When I first heard musique concrète and its assemblage of sounds, I thought, ‘This is like that thing on Rainbow I loved when I was four!’ I used to crave those moments because it was so funny and mad and unpredictable. Musique concrète was the grown-up version of the Rainbow stuff.”

Then, he turns serious. He doesn’t often interact with fans, but wants to put something good into the world. “That’s why I don’t want to recycle old ideas. There is a moral dimension.” A programme helping kids to relax has a clear and coherent social purpose. “That seems, to me, quite a noble thing to do.” Not wanting to patronise this audience, and possibly aware of the curiosity of his own mind at that age, he did try pushing a few, ultimately unused, pieces, “into more exotically harmonic terrain and came unstuck unfortunately,” he laughs. But he’s proud to have been involved and says it’s something special.

Another recent album, last September’s ‘All Night Chroma’, heard Squarepusher team up with organ player James McVinnie, composing eight pieces that were recorded over a single night on the Royal Festival Hall’s 1954 Harrison & Harrison organ. One thing DJ Mag learned from this is that an organ actually has presets, “a massive amount,” he says — at its dizzying array of stops, the parts of the instrument used to determine which pipes get air.

He has a history of listening to the organ, as he went to the Cathedral Primary School in Chelmsford. Pupils were regularly marched to the city's cathedral “to look sweet and sing. I remember this enormous sound when the organ got going and really being affected by it. To this day I have an abiding love of the traditional canon of organ music.

“Messiaen, apart from being one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, his canon of organ works is unique and very forward-looking. It’s a beautiful case-in-point to the argument I come back to time and time again, people thinking they need the new instrument and companies putting out the dogma you need the new equipment to make the new music. Messiaen made abundantly innovative music using an instrument that had hundreds of years of heritage. He still sounded futuristic, and that was the spirit I tried to work with.”

James helped show him what this “strange, powerful mechanical beast” was capable of. “It is the mother of all synths.” With a broad orchestral palette based on traditional instruments, his leanings were to the stranger, more harmonically obtuse sounds, such as flutes.

By 5am, having worked all night to avoid external noise invading the recording, everyone was tripping out from fatigue, and it felt like they were piloting a giant spaceship. “It’s funny what the organ shares with dance music,” he adds on how exciting and hedonistic the experience proved. “Unlike other traditional instruments, it has this immense capacity to shake the room. It’s more or less down to 20Hz. The last piece on the album is full tilt, we literally pulled all the stops out. That’s where that phrase comes from.”

DEDICATION

We’re nearing what feels like the end of the interview when he says there’s something to add. He normally steers away from personal stuff in interviews, but there’s an important element to ‘Be Up A Hello’. “It’s dedicated to my friend Chris who died in March 2018. I loved him to bits. He was a friend of mine in the era when I was getting to understand electronic music and the means of making it. He had a very technical mind, so we were united in that common purpose of trying to understand how samplers work, how different forms of synthesis work. It felt to me absolutely the right thing to do, being that he was on my mind through the compositional process.”

It was Chris he was larking around with in Essex in his formative years, and who he made some of his early music with. His death is undoubtedly part of Squarepusher’s looking back, although he hesitates to call it nostalgia as it wasn’t comfortable, the grief raw. It’s obviously emotional for him, speaking about this, but after sharing, a tension seems to lift and other stories from the past come flowing.

He remembers the thrilling times of ’94 and ’95, “Turning pirate radio on on Saturday morning, tearing hardstep coming out of the speakers”. It was when he moved to Hackney and lived next door to an MC who one day proudly brought around his knife collection.

Hearing that Tom made music, next time he brought his SM58 mic instead. The recording of this session was initially shelved, but a few years later Tom revisited the vocal and used it on his track ‘Full Rinse’ on 1997’s ‘Big Loada’ EP. “It’s got him saying ‘Big up all the students in the house’, because I lived with eight people then.” While he’s listed on the record as MC Twin Tub, this is a made-up name — when Tom went to find the MC, who he only knew as Lee, to cut him in on the publishing, he’d vanished and has been untraceable since. “If you read this interview, contact DJ Mag,” he says.

‘Big Loada’ also contained breakthrough hit, ‘Come On My Selector’, with its early Chris Cunningham-directed video. All the dancier tracks on the EP were recorded at 190bpm with the intention that you could get two copies and mix between them without beat-matching. It was an idea he tried to demonstrate at a live session on Radio 1 for Mary Anne Hobbs.

“They were expecting me to turn up with a bag of records, and the show was late so I arrived at 11.30pm to broadcast at midnight. I’d basically been getting pissed all day and just had two copies of ‘Go Plastic’,” a 2001 record he’d designed with the same purpose. “I tried to explain, while pissed, that you put on two tracks that are at the same tempo, then smash it around to make a hybrid. They had a little huddle and said, ‘We’re not really sure about this, maybe you can do 15 minutes?’ I did a total flounce out and said, ‘Fuck you, I’m going home’. I believe they made some kind of comedic announcement about Squarepusher leaving the building,” he tells us with a wry smile, praising Mary Anne Hobbs for her support.

We get the tube together and the reminiscence continues, the idea of never meeting your heroes so far having stood firm in regards to Tom’s respect for Derrick May. Perhaps Chris’ death is an actual Year Zero, though.

“There’s a time for rules and a time to break rules,” Tom says at one point, with the kind of clarity that comes from experiencing the loss of someone close. “I’m resolutely anti-nostalgia, you’ve just got to face forward. We’re drowning in acts coming back from the dead, I hate it. But my own rules about not looking back, sometimes you’ve got to say 'Fuck it, why not?' I’m going to enjoy it.”

The result is Squarepusher in vintage form, the gritty ‘Be Up A Hello’ majestically grand in its complexity and sheer determination to push its architecture of analogue machinery into unexplored realms. And now Squarepusher is rewriting his own rules too, who knows what’s next?