The rise and rise of Bandcamp

As the conversation about how artists can best navigate the streaming economy develops, many musicians and labels are moving towards more independent platforms, selling their music and growing their fanbase with greater control over their output and finances. Here, DJ Mag takes a closer look at Bandcamp, one of the most promising DIY platforms around

Fatalism about the music industry comes easily. News of nightclubs, DIY venues, and independent labels closing is commonplace, and streaming platforms are arguing in court for their right to squeeze artists, producers, and songwriters for every penny they can. Many artists and labels argue that streaming algorithms are skewed towards derivativeness over artistry, with talented creators feeling like they’re falling between the cracks of the industry.

Among this, Bandcamp is a ray of light: a commercially viable template for how a progressive music service can operate. Founded in 2008 by a group of software developers, the Bandcamp ethos is of artistic control and autonomy, in a business environment where both concepts are in short supply. The website gives artists their own store to sell their music, in physical and digital formats, and a journalistic platform to tell their story.

Alex Koenig produces music as Nmesh and is an active Bandcamp user. He runs six accounts on the site, one for each of his aliases. “I recall seeing the [Bandcamp] name pop up more and more in the music community in the early 2010s,” he says, “so when I finally decided [that] I was long overdue in making my back catalogue available [online], I took to Bandcamp. I have near total control of how I want to run my online store – setting my own price tags, adjusting it for sales, pre-sale options, shipping costs – and customization is a huge perk.”

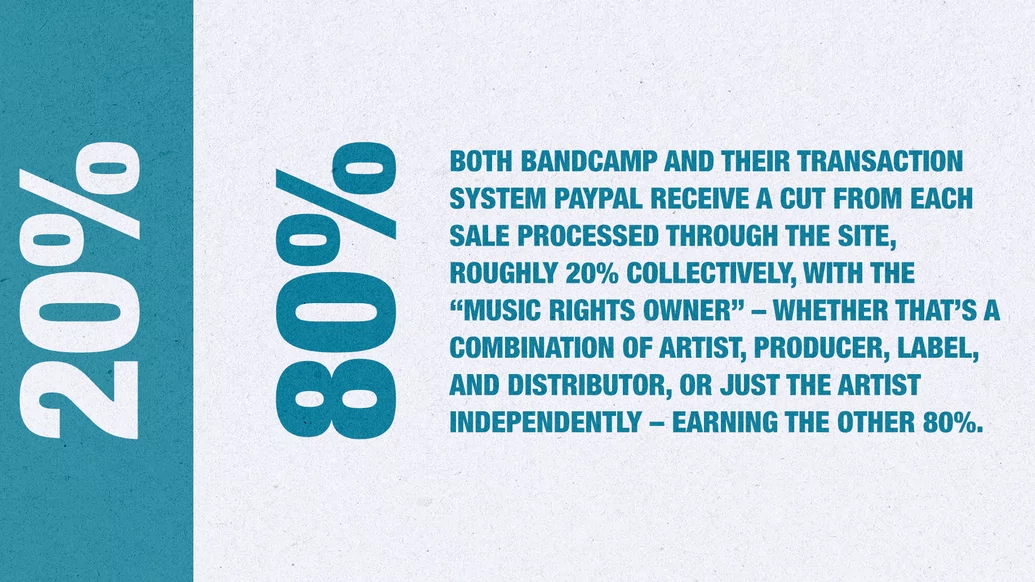

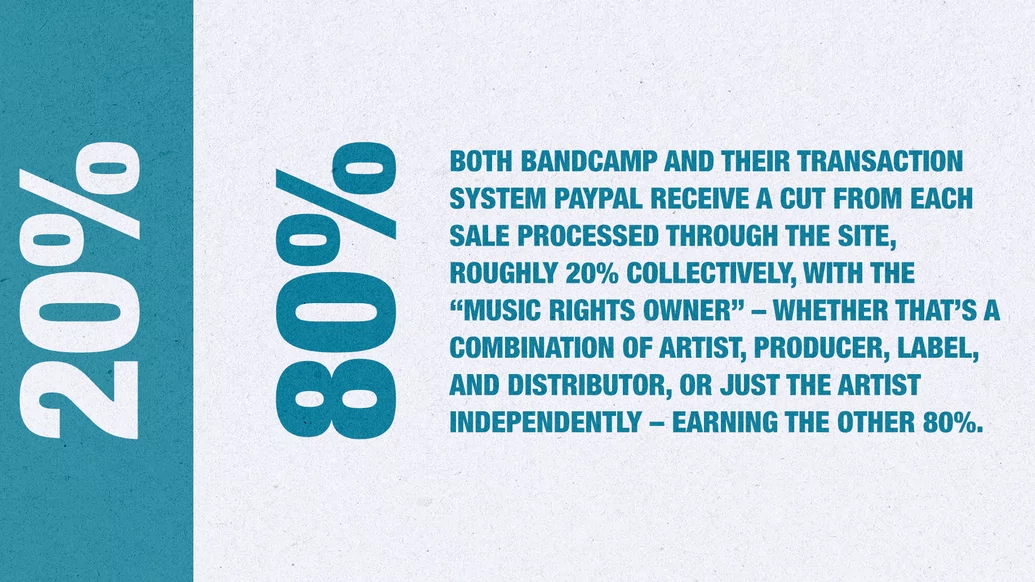

That the site can function as a discography archive and an international marketplace appeals greatly to Koenig. “I uploaded 10 years-worth of music that had never before been available digitally,” he explains. “I started to see some actual money trickle in, and my CD overstock was finally starting to move; but most importantly, I was able to make a decade of previously unheard work available to ears across the globe.” Both Bandcamp and their transaction system Paypal receive a cut from each sale processed through the site, roughly 20% collectively, with the “music rights owner” – whether that’s a combination of artist, producer, label, and distributor, or just the artist independently – earning the other 80%.

This system stands in stark contrast to other services. When an mp3 is sold on iTunes for £0.99, 50% of that £0.99 is immediately paid to Apple, and after the additional cuts for labels, distribution companies, and songwriting credits, the artist royalty might be worth less than £0.05. Bandcamp allows artists to circumvent the traditional middle-men of labels and distribution companies. They can create, promote, and distribute their music to a global audience with independence.

Bergsonist is an independent artist who uses Bandcamp. “Once you have a big following, Bandcamp is very handy,” she says. “You don’t need any press releases or vacuous publicity to support the releases. It’s definitely a model that should inspire other people to create alternative ways of distributing music. I always set my releases at $10,” she says, clarifying how she tweaks price controls to her preferences, “which after Bandcamp and PayPal’s cuts, I think is reasonable. Because I tend to see my albums as units, as singular entities, I love having the option of not allowing people to buy individual tracks. I also love that Bandcamp automatically notify all of your followers; which I think is amazing. Basically, it acts like a newsletter. If your product is good and you have a loyal growing fan base, then you don’t need to worry.”

It’s not just artists like Bergsonist and Koenig who are benefitting from Bandcamp’s progressive pricing and autonomous systems. Labels are, too. Tom Lea is the founder of Local Action, one of the first independent UK labels to integrate Bandcamp into their business model. “In late 2014, when we released [ambient artist] Yamaneko’s debut album, we tried Bandcamp for the first time because we heard it was so much better for digital music,” Lea says.

“It did £1000 on Bandcamp after, maybe, six weeks. I was like, ‘Holy shit, not only is this making us more money, and making our artists more money, [but] we’re getting the returns straight away and don’t have to wait months for digital distributors to account to you.’ That was a real eye-opener. By the end of 2014, we made an effort to push Bandcamp as a primary platform alongside Apple and Spotify.” Lea had been looking for ways to cut physical distribution costs, at a time when streaming and digital sales were overtaking traditional forms of music consumption. “We were still a very physical, vinyl-focussed label in 2013,” he explains.

“We were selling fewer records in stores, as a lot of labels were at that point. When we started the label it was very much, ‘you press 500 records – you send 50 to Phonica, 50 to Boomkat, 50 to Juno, whatever – then hopefully sell out and re-press.’ I was always curious as to how you can bring those services in-house. I told our distributor that we were going to keep 50 of Slackk’s records and sell direct. It went really well. We were selling 50 of them at £8.99 rather than the £3.50 you get after the distributor and store take their cut, and it was giving us a direct line of contact with fans that we didn’t have before.”

The direct line between artist or label and users is a convenient cost-cutting measure and an accessible system of communication. Bergsonist – who recently took part in our Fresh Kicks mix series – likens Bandcamp to a “newsletter” – to engage and grow fandoms, and to increase revenue without compromising authenticity. “The direct-to-fan model won’t be going away anytime soon,” says Lea. “Our top-selling artists, Dawn Richard and Lena Raine, both have significant Bandcamp numbers. Lena in particular has built a really dedicated Bandcamp following. We’ve made more money through Bandcamp than through stores for Lena. Prioritising Bandcamp and direct distribution has probably been the best decision for our accounts and for the financial viability of the label.”

As Bandcamp continued to grow and attract more underground artists, a new concern emerged – how do you properly filter the service to make sure quality artists get the coverage that they deserve? Some forms of coverage have emerged organically. Aidan Hanratty runs Bandcloud, a weekly round-up of his favourite underground electronic and ambient music released on Bandcamp and Soundcloud.

“A couple of years ago I tweeted a link to something on Bandcamp,” Hanratty says, “a friend of mine told me that I should set up a newsletter sharing links, and that was that, really. I set up a Gmail inbox and once I realised people were actually interested, and wasn’t something that was just going to die, I set up a Mailchimp account and I've been running with that ever since. It turned five years old in January this year - and I put a compilation out to mark that.”

Both as a content provider of sorts, and as a fan, Hanratty appreciates Bandcamp’s democratisation of music consumption; being able to see not only what your friends have bought and are listening to, but artists and labels, too. This opens up a universe of music for Hanratty to discover, enjoy, and share through Bandcloud. “You can get a digest of what the people you’re following has bought,” he enthuses. “You get an email of what they’re buying, whether that’s friends or massive DJs, like Palms Trax for example. It’s not always new stuff, either - there might be an old track they’ve bought, and that leads you down another rabbit-hole.”

In 2016, Bandcamp launched an editorial branch to complement their music purchasing and streaming operations, Bandcamp Daily, which publishes articles promoting some of the site’s artists and local scenes. Jes Skolnik, Bandcamp Daily’s senior editor, came from the world of DIY punk shows and local zines, so understands how crucial it is for artists to have a platform.

“From the very beginning,” Skolnik says, “the mission statement has always been to provide a look into the depth and breadth of the music on Bandcamp from the perspective of humans, not algorithms. A discovery feature, in the way you’d find in a giant record store. Think of [it as] a music journalism version of staff picks, a friend telling you something they're really excited about listening to. The wealth of music we have access to in the streaming era is so immense,” they continue. “It’s easier than ever to record music, to distribute music, yet it's just as difficult to get it surfaced into the mainstream.”

Skolnik stresses that Bandcamp’s prerogative isn’t about promoting artists at the expense of labels or distributors, but about manifesting a strong digital space for existing underground communities. “It’s not necessarily the idea of circumventing the traditional system so much as it is maintaining a healthy DIY system that's always existed; including labels,” Skolnik says.

“I think the direct-to-fan model also benefits artists who use labels, as it helps them feel connected to their fans without it crossing boundaries; the way artists interact with fans on Twitter can be stressful for everyone. Whereas getting a little personal email from an artist telling you they’re coming to your city, there’s that connection without the potential for abuse. We should be providing a digital translation of those indie community networks that are really vital for music in general, as well as making it a more equal playing field for folks.”

Inherent in the levelling of the playing field for artists is challenging the status quo of the streaming giants. “As much as Spotify’s model is not what I would choose for personal and political reasons, I think of it more as radio. It plays the same role as radio always did, and I think Bandcamp and solutions like them as being more akin to indie record stores and merchandise tables. Hopefully, in a healthy economy, there will be lots of viable ways to do this,” Skolnik elaborates. “The worry is when it becomes one, a monopolising system.”

Hanratty agrees that you “might just end up with two audiences - the audience who want to own music and be involved, and your audience who are happy with the convenience of streaming platforms.” He’s concerned that the monopoly of subscription-based streaming might alienate fans who can’t afford to pay, or have no interest in paying these companies.

“I got an advance album yesterday and the stream links were only Spotify and Apple Music,” he says. “I'm not complaining about streaming. Bandcloud has access to Bandcamp links all the time. But those are things you don't need to have a subscription or specific app for. I find that, if you're not on Spotify, it’s likely you might be left behind. The industry is gearing towards subscriptions.” He is cautious of streaming services’ domination not only for marginalising other listening platforms, but for normalising the concept of not owning music, of renting art. “I don’t like not owning music,” he says. “If you look at Netflix, that TV show you're watching might just be taken off the service. What's to stop that happening on Spotify or Apple Music?”

Koenig agrees that “listeners stream out of convenience,” but is also wary of the music industry eventually becoming tired by endless court cases and just accepting streaming’s miserly practices. “The problem is,” he says, “artists will never be able to quit their 9-to-5 jobs if they were to rely solely on streaming payouts. If that’s the future, we all need to start swapping our press kits for professional resumes.”

The fear that streaming might displace ownership is understandable, but Bandcamp’s success envisions an alternate future. In February 2018, the site announced that 600,000 artists had sold something through the site, with payments to artists exceeding $270 million. As of this week, that figure had soared to $421 million, with $8 million of that spent in September alone. Bandcamp’s growth is mirrored by fellow download sites such as Beatport, whose revenues have grown for three consecutive years.

Compounded by the still-sustaining vinyl resurgence, the market, on the one hand, suggests a u-turn towards music ownership again; but streaming is stronger than ever, with Spotify reaching 100 million paying users globally this year, and Apple Music exceeding Spotify in US-based subscribers this April. All signs delineate an audience simply consuming more music, in all forms, than ever before. Is this dualism between ownership and streaming the future as well as our present, or will the levee break for one?

Even more concerning is how streaming affects our instinctive relationship to music. Streaming, without demanding attentiveness or considered thought on the listener’s part, might be radically, unalterably, changing the way we listen to music. It is repurposing it as background noise we process passively, a consumption of convenience. As Liz Pelly wrote in The Baffler: “All of this caters to an economy of clicks and completions, where the most precious commodity is polarized human attention - either amped up or zoned out.”

The biggest loser in all of this isn’t the listener, but the artist, whose art is reduced of its beauty and numbed into muzak. Bandcamp in its small way offers an antidote to this - a snapshot of fans remunerating artists not just for their product’s value, but for their art’s resonance and meaning. The organisation stated last September that 40% of fans pay more than the minimum price for releases.

“If I'm having a particularly bad day,” says Skolnik, “I take a look at the front page of Bandcamp to see how often people give more than artists are asking for. It happens with such frequency, way more than you'd expect it to. People are thinking 'I care about this musician, I care about their music, I want to put a couple more dollars into their pocket’. It upholds the idea that art has value,” Skolnik asserts, “and if you love and enjoy something you should compensate that artist fairly. At Bandcamp we see people investing in music, and it’s incredibly heartening.”