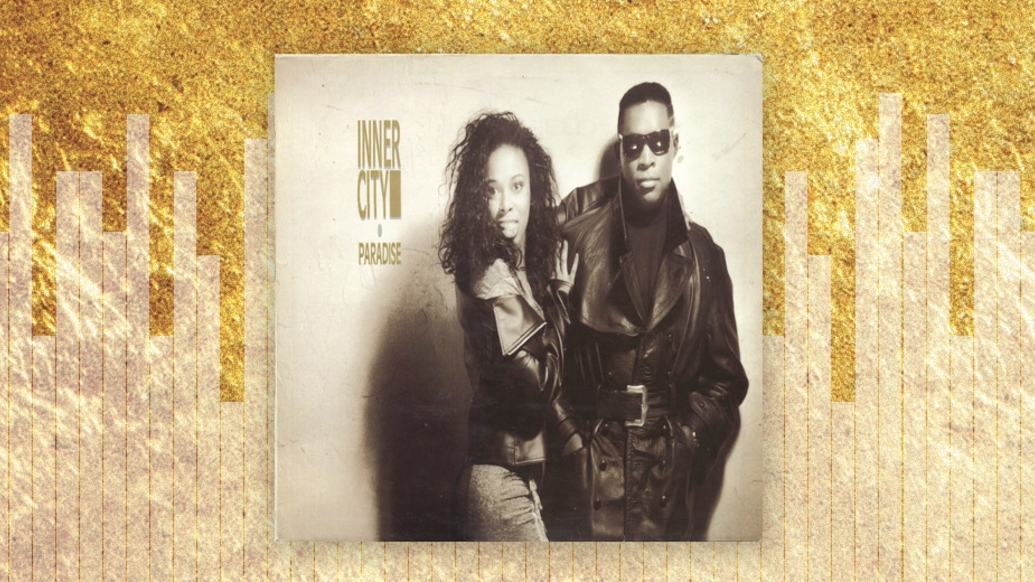

Solid Gold: How Inner City’s 'Paradise' linked Detroit techno to the Motor City's Motown heritage

Combining the creative futurism of techno with the melodic buzz of disco, Inner City laid the template for upbeat dance music albums

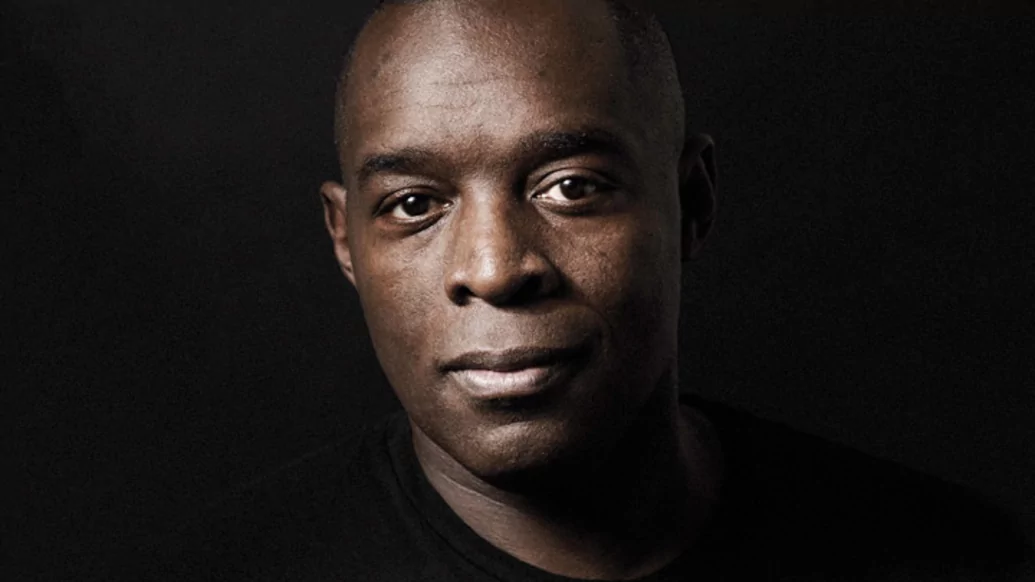

That Detroit gave Motown to the world, two decades before it birthed techno, is a historical fact that if not exactly ignored by electronic music fans, is not as widely acknowledged as it should be. ‘Paradise’, the debut album from Kevin Saunderson and Paris Grey’s techno soul project Inner City, is a link between the two, home to the kind of soulful R&B precision that Berry Gordy would have been proud to call his own in the 1960s, as well as the glorious electronic futurism that Saunderson and other Detroit producers pioneered in the 1980s. As one of the Belleville Three alongside Juan Atkins and Derrick May, Saunderson played a key role in the birth of techno. But the music he and Paris released in the late ’80s and early ’90s was different from most of the Motor City’s output at the time. Inner City were light, where techno was dark; positive, where techno was dystopian; a pop act you could see on TV as opposed to another producer credit on a faceless 12-inch.

“Juan had visions of futuristic, funky synthesiser music, a cross between Kraftwerk and George Clinton, and was the first to make what became known as techno under the names Cybotron and then Model 500,” Saunderson told The Guardian in 2019. “That inspired Derrick but I’d been to the Paradise Garage in New York and wanted to use Inner City to create Detroit techno, but with a disco feel.” It’s a point of difference that is reflected in the band’s name, which celebrates the possibilities of the inner city, rather than lamenting its woes. “It was a positive and deliberate choice you know,” Saunderson told Moo Kid Music in 2019. “An ‘inner city’ can be an elevated thing rather than something really dark, like in other techno.”

That Inner City were different was evident from their debut single, ‘Big Fun’, released in 1988, the same year that Juan Atkins’ Model 500 put out the acidic classic ‘Interference’, and Derrick May, as Rhythim Is Rhythim, released the jazzy beast ‘It Is What It Is’. While all three tracks share a gleaming futurism, ‘Interference’ and ‘It Is What It Is’ were broody and foreboding, while ‘Big Fun’ was a riot of positivity, featuring a gigantic vocal line you could hum in the shower long after the rave had worn off.

Much of the credit for this goes to vocalist Paris Grey (born Shanna Jackson), a gospel singer from Chicago who had previously appeared on a number of early house records, including House Master Baldwin’s wonderfully yearning ‘Don’t Lead Me’. Baldwin recommended Grey to Saunderson, who had been plugging away on ‘Big Fun’, and one of the most fruitful partnerships in dance music history was born. The subsequent chart success of ‘Big Fun’ — it reached number eight in the UK — was both unexpected (no Detroit techno record had ever been that big) and inevitable, with the record’s mixture of soulful synth stabs, racing drum machine and R&B vocal hooks proving utterly irresistible.

‘Good Life’, which followed months later, was even greater, a titan of electronic soul that nailed the poignant ecstasy of the very best pop music, from ABBA to The Supremes. Grey sang with the perfect melancholy that suggests that good life will in fact end one day soon, which makes it all the more worth celebrating right now. “I’d grown up singing in church and had been a girl scout and a cheerleader, so lyrics about positive thinking and good vibes came naturally,” Grey told The Guardian. “The ’80s had been very hard for people: ‘Good Life’ and ‘Big Fun’ tapped into a feeling that things were getting better.”

The production, meanwhile, is dazzling; a mixture of echoing synth riffs, electronic strings and tough drum hits that was simultaneously stripped back and epic. “30 years later, ‘Good Life’ still instantly gets people dancing and feeling good,” Saunderson told The Guardian. “It’s funny, because there’s not much to it: a TR-909 drum machine for the beat and a TR-707 for percussion, Casio and Korg keyboards and a sampler.”

‘Paradise’, the album that followed in 1989, is inevitably dominated by these big hits. But there is far more to ‘Paradise’ (renamed ‘Big Fun’ for the North American and Japanese markets) than just those two cuts. ‘Ain’t Nobody Better’ has a brilliantly slinky vocal that nods to Janet Jackson’s techno futurism on ‘Control’, ‘And I Do’ features a heart-racing bpm and darting keyboard line that point towards the nascent hardcore scene Inner City would later embrace on songs like ‘One Nation’, while ‘Power of Passion’ (replaced on the US edition of the album with ‘Whatcha Gonna Do with My Lovin’’) is almost certainly the first techno ballad, combining leisurely drum-machine programming with a vocal that drips with craving and lust. Album opener ‘Inner City Theme’, meanwhile, is a powerful ode for people to come together that plays out over sky-busting chords.

Throughout the album, Inner City keep their standard almost impossibly high. The synth lines have the musicality and futuristic sheen of the best techno records, frequently bolstered by electronic string melodies that point to Saunderson’s love of disco, while the drums swing with a wonderfully live feel. The production feels electric and fizzing with life, while Grey’s vocals are masterful, combining flawless technique (check the high notes on ‘Ain’t Nobody Better’) with an incredible expressiveness that can flick from out-and-out celebration on ‘Big Fun’ to the melancholy release of ‘Set Your Body Free’.

The songwriting is brilliant too. No one is suggesting that you should strum out the 10 tracks of ‘Paradise’ on your acoustic guitar when next around the bonfire — but the fact that you could if you wanted to says a lot about the album’s songwriting craft. And it is this, more than anything, that made ‘Paradise’ so influential. There had been house and techno albums before ‘Paradise’, and Inner City were far from the first group to marry vocals to electronic music. But house and techno were still dominated by 12-inches and one-off tracks.

Inner City not only made a full album of songs — ones that deserved to be placed alongside classic Motown and disco tracks — but they took it to the higher reaches of the charts, with ‘Paradise’ making number three in the UK, 21 in Germany and a respectable 162 in the US, which lagged behind Europe in its appreciation of electronic music, even as the pioneers in Detroit, Chicago and New York were forging ahead with house and techno.

You can hear the influence of Inner City on everyone from C + C Music Factory to Underground Resistance offshoot Happy Records, from Technotronic to Madonna (whose 1990 track ‘Vogue’ contains a definite whiff of Inner City’s soulful techno mix). In fact, it wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to see the influence, direct or indirect, of Inner City on pretty much any house or techno act since that combined soulful songwriting with a certain grit.

Inner City would release two more studio albums — 1990’s ‘Fire’; and 1992’s ‘Praise’ — that would incorporate breakbeats and electronic swing before drifting apart in the early ’90s. But their classic songs have never been far from DJ’s record boxes, always there in case the dancefloor needed an injection of soulful release — and Saunderson resuscitated the group, sans Grey, in 2017. That the highlights of their live shows to this day include songs from ‘Paradise’ is tribute to one of electronic music’s most profoundly joyful albums.