What is the future of techno tourism?

Major cities have long been the central hubs for dance music, in part thanks to their appeal to travelling DJs and fans. With coronavirus massively impacting tourism, however, even when clubs do reopen they could face severely reduced crowds and income. DJ Mag speaks to researchers and music industry experts about what this could mean for the future of city clubbing

What a difference 12 months makes. This time last year you might have been making travel plans for Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE), getting final kicks from a summer of festivals, or on a trip to Ibiza. Times change. Pausing the global events industry cuts deeper than losing a weekend in Berlin — so many livelihoods are on the line, it’s devastating. But this side of the COVID-19 catastrophe is compounded by dance music’s reliance on ‘techno tourists’ flowing into key nightlife centres. That weekend break is no longer a no-brainer, even within your own country: it’s a crisis within a crisis.

A UK Music report from November 2019 noted that 11.2 million people travelled domestically and internationally for music events in 2018, accounting for more than one-third of the total tickets sold in the country that year. London had the biggest draw, with 2.8 million hitting the capital for its soundtrack, followed by Northwest England; Scotland enjoyed the biggest year-on-year increase, attracting 1.1 million. Across the North Sea, October’s ADE is the world’s biggest electronic music festival and conference. 400,000 attended last year, with passes held by over 100 nationalities. And that’s hardly Amsterdam’s only big sell, with weekenders like Dekmantel and Awakenings, and venues such as Radion and Shelter offering year- round temptation. Berlin, meanwhile, welcomes more than 3 million club tourists every year, and Ibiza has long been an island with a love-hate music tourism dependency.

As the COVID-19 crisis progresses, travel is becoming less predictable. At the time of publication, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Spain and the Netherlands made the quarantine list for arrivals into the UK. According to the IATA (International Air Travel Authority), 80% of us believe planes increase the risk of catching a virus, and the priority is rebuilding public trust in terms of safety, not simply bringing back supply. You can understand why German airline Lufthansa doesn’t expect passenger demand to return to pre-COVID-19 levels until 2024.

So what does this mean for cities that depend on vast numbers of nightlife visitors? Can home crowds plug the gap if events return before travel does? And, given that the climate crisis was our top concern before coronavirus took the spotlight, should we even be aiming for business as usual?

More City, More Problems

The Centre For Cities is a UK think-tank that analyses socio-economic data about towns and cities, and its research confirms what most of us knew; cities disproportionately dominate partying. In the UK, 45.9% of nightlife establishments are within city boundaries, but these only account for 9% of the land mass. The bigger the place the more options there are, so relatively niche things — like feral techno basements — are heavily centralised in larger cities, which act as magnets for wider areas. For somewhere like London, that extends far beyond UK borders, meaning the impact of COVID-19 travel disruption on nightlife will be much more pronounced.

Lahari Ramuni, a researcher for Centre For Cities, looks at the functions of cities through their High Street Recover Tracker: like what share of daytime and nighttime workers are returning to the city now, compared to before lockdown began, and comparing the scores of different cities on Friday and Saturday nights. “Smaller cities are much less affected,” says Ramuni. “It comes down to four factors — lack of tourists (and for anywhere like London, that’s huge), public transport, localised centres, and the number of business premises that still do not have all staff on-site. London currently has about 25% of the activity it had before [lockdown].

“We are seeing the number of people in cities on weekends begin to increase, and the pattern is consistent in terms of nighttime and weekends — smaller cities are recovering faster,” she continues, admitting that the situation is volatile. “Even if we just look at local lockdowns in terms of public confidence, we don’t know the scarring that’s being caused, and what will happen when things return after taking a step backwards.”

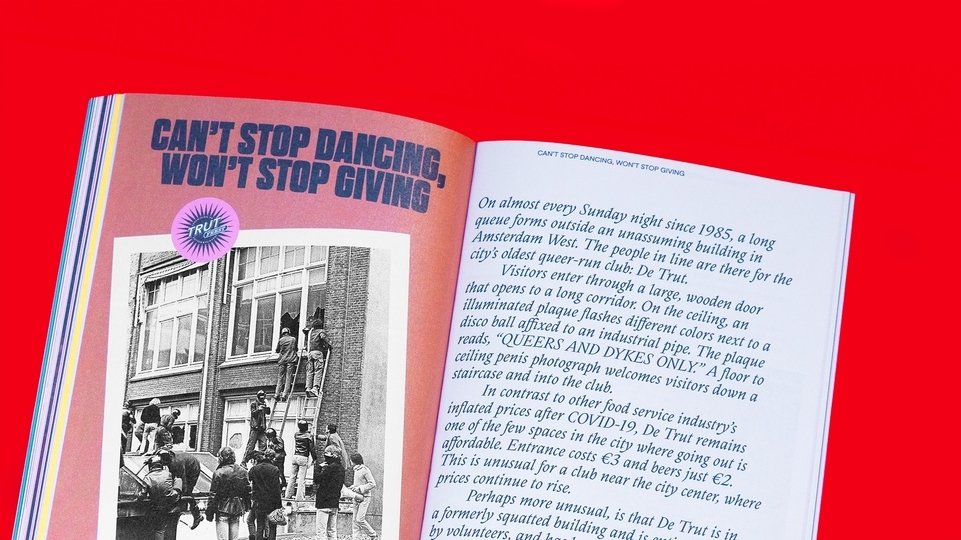

Dutch Courage

If London needs more tourists, Amsterdam doesn’t — or didn’t. The Dutch city is the planet’s second most-visited per head of population — the 1 million people who live there welcome around 20 million tourists each year. In 2019, the City In Balance initiative began, essentially curbing tourism growth by stopping new hotels, souvenir shops and more from opening. Nightlife is one of Amsterdam’s core attractions.

“Club culture, as we have known it, is not possible [right now],” replies Ramon de Lima, the Night Mayor of Amsterdam, when we ask about events returning. His office provides a crucial link between the city’s nightlife and local authorities. “I don’t know the exact numbers of tourists who come just to visit the nightclubs, but I know what the entertainment district with smaller bars and restaurants is like. They rely on tourism from abroad and from around the Netherlands. I think they will still have a hard time when we reopen the clubs, the ones around that area rely on people from outside Amsterdam.

“I think it will impact the club culture, definitely,” he continues. For any event, not least those with global appeal, endless postponement is a serious problem. “The event organisers won’t make any new money from the event, but will carry many new costs. They planned their [quarterly] marketing budget in April, with big production costs being paid [in advance], but while the next event will need this budget again, they won’t be able to sell many tickets. We are just moving the problem onto the next edition.”

While appointing a Night Mayor may outwardly signal that Amsterdam has a progressive attitude, de Lima is quick to point out that the scene can’t survive on goodwill and reputation alone. He sees focused support from the Dutch government as crucial. “A month before recess, I spoke with people from parliament about supporting the nightlife ecosystem, so that venues, workers and promoters can survive financially. We’re starting off with not a lot of local clubbers and no tourism, but we have to keep going.”

“I don’t think it’s necessary to say ‘we must go back to normal’. This is a progressive scene, so let’s focus on the future... We should think about what we can do better, do differently. This crisis should maybe make people think more regionally."

German Engineering

Berlin is seen as a model for nightlife management — a place where clubs were seriously campaigning for the same cultural status as opera houses until COVID-19 hit. The city’s Club Commission supports and fosters nightlife organisers. Club Commissioner Lutz Leichsenring says that, despite the world famous local scene and its strong nightlife infrastructure, Berlin’s venues also face tough times without tourists. “In our survey, two-thirds of Berlin clubs have liquidity to survive for a maximum of three months in the current circumstances, and 17% only have that security for four weeks,” says Leichsenring. “We need to prioritise these places. The majority will need assistance.” Many venues are concerned about covering basic costs like rent and staff pay, not about putting on parties during a pandemic; the idea of ‘policing’ parties through social distancing restrictions feels antithetical to Berlin’s famed rave ethics.

So the loose plan is to stay closed until a vaccine is widely available, and the focus is on government support until then. But this doesn’t account for the prospect of significantly fewer people coming back once parties return. “30-40% of club-goers in Berlin are visitors, tourists. Right now tourism is basically a ‘No’. So even if we can open the clubs, there won’t be enough people for all of the venues [to operate without a loss],” says Leichsenring.

Is a return to business as usual possible for Berlin, then? “I don’t think it’s necessary to say ‘we must go back to normal’. This is a progressive scene, so let’s focus on the future,” he says. “We should think about what we can do better, do differently. This crisis should maybe make people think more regionally, more sustainably. Maybe the clubs that were only surviving because of tourists, and will struggle without them, should invest in the local scene in terms of bookings and audiences.”

Managing Expectations

“The travel thing is just so confusing. If people are tentative about venturing to a club event, I can’t see many promoters putting money where their mouth is to make an international booking [happen] when they could do a similar event using locals,” says James Ruari. As a UK-based manager, working with artists such as Matthew Dear, Glenn Underground and Kiara Scuro, he’s been gauging the sentiment among artists about travel, and the likelihood of promoters booking the kind of headliner-heavy line-ups that once had us scrambling for Skyscanner.

“The US artists seem to be the most realistic, as they’ve been used to doing long-haul [touring] more often. Now, they seem to be saying, ‘It’s not happening this year’. I can’t see any semblance of DJs travelling to clubs and parties [like before COVID-19] right now,” he continues. If events don’t return en masse by this winter, it could mean a 12-month break for many promoters. Nobody knows what this might mean for an industry often led by trend-based headliners.

“It’s not just going to start up again, is it? And who’s to say it’s going to start back up again with everyone viewed the same as they were? A whole year is going to have passed, if not more. Who are the headline acts, and who are the fresh faces? You might assume the same names will have the same pull for ticket sales, but that’s not a certainty,” he says. Again, the conversation moves to events becoming more localised. “There needs to be something good to come out of all this. It would be great if people didn’t have to go to London or Manchester for quality dance music in England.”

Local Benefits

Before COVID-19, regional promoters often struggled to compete with the scale, marketability and financial viability of major nightlife cities. Ahmet Sisman is responsible for The Third Room, an event series in Essen, Germany. The industrial area had a strong techno heritage, but has seen its crowd increasingly drawn to cities like Berlin. Regular club-nights are difficult, hence the crew using statement locations like UNESCO-listed Mischanlage. Once the largest coal mine on the planet, it’s a venue that can match any for spectacle, bringing heads from across the country and beyond with help from equally impressive line- ups. Sisman agrees that, when events return, the approach will probably be very different.

“People are talking about [COVID-19 being] the biggest economic crisis, maybe bigger than the 1930s. People will have less money, so how should a promoter put an event together? My first thought is for the community, for local line-ups,” Sisman says. “The first wave could be okay for smaller cities — it doesn’t matter who you book, the first parties are going to explode — but people’s habits will change.”

There’s a real concern over how long it could take for crowds to come back, particularly around those willing to travel; it’s an understandable concern, too, given the recent experience of an open-air edition of Third Room featuring Blawan, Gerd Janson and Vnnn. The party complied with all pandemic regulations, but was pulled due to poor sales.

“I think I was living in a bubble,” Ahmet admits. “I thought, ‘This is the first event in five months, there will be hunger’. No, there’s not so much hunger, not when there is something they don’t know. We can’t predict if this pandemic is going on until next summer, and we don’t know how much more people’s habits will change in that time,” he continues; since so much has already been wiped out, he reiterates an urgent need to rethink what dance music places its value in.

“Our music culture is also a mirror of society: they are not independent of each other, they are one. It’s a discussion of capitalism, too. How do we want to see the world after COVID-19? We can’t go on like before. The conversation needs to happen in the music industry, but it’s not happening yet.”

Much Worse - Then Maybe Better

Nobody is expecting a simple recovery from COVID-19’s economic and social fallout. When it comes to clubs, and crowds, the problems could manifest in three ways — we have less cash to spend, so we do less socially, we remain cautious about travel, and about what makes dance music culture precious. Bonding in darkness with strangers, freedom of movement, sexual expression and anonymity are often intertwined with nightlife — and impossible under current regulations. This leaves many of our treasured spaces unable to break even, let alone turn profit, until events — and capacity — fully return. But by only focusing on that watershed moment, whenever it comes, we underestimate the reality of a globalised music event industry that has hit the wall, and is likely to be one of the last sectors to return.

“It’s the biggest crisis in nightlife since World War II. For 80 years, there has been nothing with this level of impact on our culture,” says Leichsenring of the pandemic. The task of delivering support to nightlife is so huge that he’s begun work on nighttime.org’s Global Nightlife Recovery Plan. A free online resource involving Harvard University academics and Mirik Milan, a former Amsterdam Night Mayor, the initial focus of the GNRP is on core cities, reflecting the complexity and breadth of situations in different places. “It looks at how different cities are dealing with different aspects — Vilnius compared to New York City, or Berlin. It’s about getting together best practices so people can see the ideas that work, where, and why,” Leichsenring explains.

It’s logical that, until we can predict travel more accurately, crowds will be unable, or unwilling, to return in the numbers that many venues need to survive. The process may also take so long that government financial support, if there is any, will possibly run out before parties can return, forcing venues to close. The paradox is this: the industry, so dependent on travel to function, was already in urgent need of change, particularly due to the climate crisis. Now, the challenge is finding ways to create sustainable nightlife ecosystems without sacrificing existing infrastructures. It’s a tall order, but they say real change only happens when a system collapses, and things are looking pretty broken.