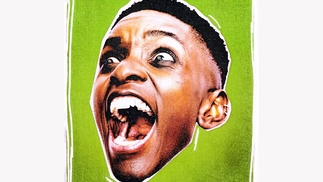

60 SECONDS WITH...CONGO NATTY

A true jungle soldier

Congo Natty has a rich history of involvement in the music scene for the last 25 years. Formerly known as the Rebel MC, he had chart hits such as 'Just Keep Rockin'' and 'Street Tuff' in the late '80s with the Double Trouble production kru before hankering down into — and helping to pioneer — the early jungle scene.

A true jungle soldier, Congo has been responsible for a slew of underground jungle tunes under a variety of aliases such as Conquering Lion and Tribe Of Issachar, and has now teamed with the Big Dada label to put out 'Jungle Revolution', his cracking new album of conscious dubwise jungle. Off the back of 'Jungle Revolution' he'll be touring – either as a DJ with assorted MCs and singers, or his Congo Natty live band – and “spreading the jungle love to as much people as we can”...

When you were doing the Rebel MC stuff with Double Trouble, some people saw it as pop, but it was actually the accessible end of hardcore hip-hop or street music or whatever at the time, wasn't it?

“Yeah, 100%. The tag of pop comes with the fact that it becomes successful and is then taken on by the so-called pop world. The tunes themselves are nothing to do with pop. We're anti-pop, from day one I never loved pop. Pop music has never been something that I could relate to in no shape or form.

For when I was a yoot, it's always been about the bassline and drums and frequencies, y'know? “There's a Catch 22 with pop. Bob Marley's not pop, Jimi Hendrix ain't pop, but they became very very popular. So when pop music tries to go on like it's something special, they have Jimi and Bob in there, but really it's nothing to do with Jimi and Bob. Pop music itself is bullshit – Kylie Minogue and all that, it's not real for me personally.”

You were there at the start of jungle in the early '90s, weren't you?

“Well, jungle didn't start in the early '90s. Jungle started... You see, there's a brother called Lord Kitchener [calypso singer], come off the boat from the West Indies, and the first thing that he did was play a tune and bust some lyrics. See, that's jungle. Jungle comes through the spirits of people who came here, and they came with that frequency, that b-line, that rave – that different thing that wasn't happening in these countries.

Jungle really is a fullness of everything that happened before. “Jungle incorporates reggae, hip-hop and everything that was before that was revolutionary. You know the Nyabinghi drum? Jungle incorporates that, cos it's a timeline, so jungle goes from the beginning of the timeline – and it's future and present. “They tried to make it so that jungle was a fad – a fashion – and that artists were only going to be around for a little while, and it was just an Amen break and a couple of reggae-man on it, or whatever. Yeah? But that's not jungle. Jungle's divine, and jungle came to give us inspiration as British yoots.”

What was exciting about the early days of jungle?

“That total musical freedom. Didn't have to have a chorus, didn't have to have the structure that they told us was music, plus we didn't have to be in the green – we was in the red light. So all the equipment, we turned it upside down. We were like revolutionaries, in a way we were like Tubby and dem man in the dub world, when they took a riddim and suddenly changed it from just being a vocal reggae tune into a supersonic dubwise ting.

They were using similar equipment to what British producers were using, but the way Scratch Perry would use the equipment was totally revolutionary. And that's really what jungle was like. We was getting this equipment that everyone had, but the way we were using it... that was the beauty of the Nineties.

“And everyone had their sound. If you spoke to Smith & Mighty, you know that they got their sound. If you spoke to Shut Up & Dance, they got their sound. And you'd know who was who. A certain tune would come on, you'd kind of know where it was from. Within our music, everyone had an individual sound. What you've got now, you're not sure who's who now. You hear a tune and it could be anyone.”

Your shout-out “Alla the junglists” appears on one of the first tracks to reference jungle (by Pascal, aka Johnny Jungle) – is that right?

“First tune to reference jungle – what year was that? There was quite a lot of tunes that claimed to be the first tune to reference jungle, I can't really be sure of this tune – you'll have to send it to me. “We were saying 'jungle music' from time. We were calling it jungle beats, and when you check it now in retrospect it was very similar in a way to Zulu Nation – in the fact that they started to look to Africa. The term 'jungle' is coming from some African vibes – a jungle ting. It's also reminiscent of a kind of awakening.

You know in New York, the man dem woke up and started like organising themselves, they started forming the Zulu Nation, they started to be more like an organisation – and hip-hop grew from that. People forget about hip-hop being this revolutionary music, yeah? Because hip-hop now is pop. Not real hip-hop, cos real hip-hop is always going to be the same, but I'm talking about the way that society and media will talk about hip-hop. “With jungle music, everyone kinda woke up again. That's why jungle is so important.”

Is it still a revolutionary music?

“It is right now. If you think about the fact that you've got dubstep, the grime scene, drum & bass... Jungle is still not owned by the labels, it's still free. It's still revolutionary, it's still not a part of the corporate society. That's why it is the revolution, and why it's hard for us to get plays on radio and things on certain channels, yeah? It's revolutionary. People wanna hear the lyrics that we're saying. “When jungle was bashing up the place and there was nuff vocal tunes, all of a sudden people started saying they don't want vocals in the tunes. It was all about taking off the vocals. But were you taking off the vocals cos you don't like the vocal, or because there's a message in that vocal? Cos jungle's got a message – and the message is anti-establishment. Music's about discovering the origination of things and knowing the message of what is in the music.”

On your 'UK Allstars' tune on the new album, you work with Sweetie Irie, General Levy, Tenor Fly, Tippa Irie, Top Cat... some of the most legendary UK MCs. Why have some of these legends been under-appreciated by the mainstream media?

“I feel that it's due to the fact that when you're doing music with a message – and also that you're real and you can't be manipulated – then you're not really any use to the system. The system wants to make you famous only so that you can turn around and sell products for them. You become a Point Of Sale, and the more famous you become, the more brands attach themselves to you. Until suddenly you're selling your own after-shave. And suddenly it's not about you anymore – you're a marketable product, and you can be used, and you know when to sit down and stand up, and you know when to smile. “Real musicians come along, and they don't play that game. They're into music. It's all about people that can be controlled and manipulated becoming more successful than those who cannot be. It's a sad thing, cos it means that a lot of MCs don't eat food. They have to go and get a job, a nine-to-five, and then they have to juggle working and trying to do MCing and producing.”

Has anyone ever asked you to put your name to your own after-shave, or similar?

“Nah, nah, I think they know with certain artists what they represent, so no.”