OLD DOG, NEW TRICKS

In an exclusive adaptation from his new book on the ever-so-slightly eccentric Godfather Of Funk, KRIS NEEDS looks at George Clinton's influence on the electronic dance music we know and love today...

George Clinton stands alongside James Brown, Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone as among the most visionary and influential black music pioneers to emerge from the incendiary '60s, reflecting the turmoil of a country ravaged by war while his bands Parliament and Funkadelic recast funk under his “free your mind and your ass will follow” banner.

Clinton’s colossal impact on dance music is often overshadowed by outrageous antics which put rock in the shade when it comes to unfettered excess. Accounts of his seven-decade story are usually dominated by tales of getting naked onstage, recording albums on super-strength acid, guitarists sporting oversize nappies, kamikaze drug-guzzling contests and, of course, the full-size Mothership landing onstage during his '70s arena extravaganzas.

Even at the recent International Music Summit (IMS) in Ibiza, where Clinton was a keynote speaker, the party tricks got more attention than achievements. These include revolutionising funk by mating it with rock (and vice versa), inventing psychedelic soul, becoming the most sampled artist in hip-hop and laying foundations for electronic dance music with the synthesised funk of the late '70s.

The walloping electronic crush-groove unleashed by long-time P-Funk keyboard colossus Bernie Worrell on 1977’s 'Flash Light' (originally intended for star-bassist Bootsy’s next solo album) was enough alone to underpin disco’s next incarnation as boogie, Prince’s breakthrough tracks, New York electro and early Detroit techno. 1978’s 'One Nation Under A Groove' became one of the immortal club anthems of the '70s (and the nearest Funkadelic got to a signature song).

Dancefloors would erupt at the first belch of Bernie’s electronic bassline and heavyweight clap-track, before the haunting harmonies and sensuous vocals oozed into the collective soul as both call-to-arms and declaration of defiance (“Nothing can stop us now”). A more ebullient, discofied version of the “free your mind” philosophy, the song predated the global dance anthem.

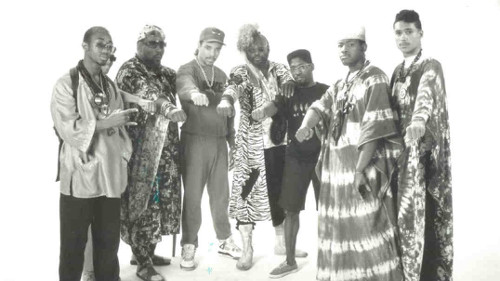

Whole underground dance movements have been stoked by P-Funk. Afrika Bambaataa’s 'Planet Rock' appeared in 1982 to kick-start electro with its percolating hybrid of Clinton and Kraftwerk. Bam’s Soul Sonic Force also adopted Parliament’s inter-galactic superhero look with their space warrior comic book costumes, building a sci-fi mythology elevating The Funk as saviour of mankind. In 1984, Bambaataa told this writer, “We came with that whole Parliament-Funkadelic look because most rap groups looked like The Temptations. I said, ‘I’m coming out like George Clinton’, wearing all kinds of shit.”

Like Clinton, Bambaataa despised musical boxes, declaring: “When I first started I was playing heavy metal, funk rock and new-wave. Everyone wanted to know who was this young black guy playing heavy metal to all-black audiences. I used to play the Rolling Stones, Clash and Blondie and everyone would bug out! It all depends on how I mix it and when I play it. There’s funk ‘n’ rock, rock ‘n’ roll, jam roll... music is music, y’know what I’m sayin’?”

BAMBAATAA

BAMBAATAA

Displaying the cyclical nature which would characterise electronic music in the future, Bambaataa influenced Clinton right back when the latter embarked on his early '80s solo career after the Parliament-Funkadelic Mothership came crashing down in a tangle of legal problems.

1982’s 'Computer Games' album brought Clinton’s old concepts to modern dancefloors as his original sci-fi visions came to life in the way technology was starting its inexorable rise to become today's all-encompassing obsession. First single 'Loopzilla' planted his DJ patter and snatches of old hits over juddering boogie-funk, biting 'Planet Rock' and Zapp’s 'More Bounce To The Bounce' with a smattering of Four Tops and Supremes over a slavering turbo-funk monster, with a bass croak not unlike a Japanese movie monster’s heaving bowel movement. George name-checked New York’s major black music radio stations WBLS, KISS and KTU — then leading the field turning the ‘mastermix’ editing concept into the artform which would go on to influence acid house.

Clinton’s triumphant return was compounded by the appearance of 'Atomic Dog' in December 1982. Cleverly grafting traditional P-style word play onto a panting electronic groove beast, the track struck an erogenous public nerve which plunged the world’s clubs into a leg-humping, tongue-slobbering canine frenzy with its “Bow-wow-wow, yippee yo yippee yay” chant. Using the backwards drum-loops which would soon be adopted by Detroit’s techno militia, P-Funk had created a massively influential new dance sound which sent shockwaves through the burgeoning hip-hop movement and provided the blueprint for G-Funk the following decade. The single toppled Jacko’s ’Billie Jean’ off the top of the US R&B charts in April 1983, staying there for four weeks.

'ATOMIC DOG'

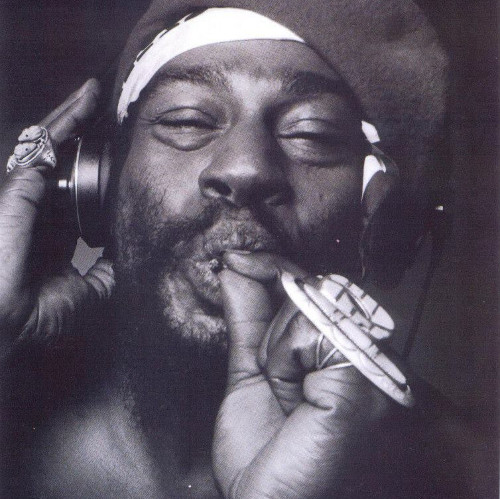

Like many of Clinton’s landmarks, his most epoch-making sound yet was created by his hyper-creative band members before he put on his stamp to elevate it. Keyboards player David Spradley spent five hours building ‘Atomic Dog’'s backing track on a snowy night at Clinton’s favourite United Sound Studios in Detroit. When it came time for George to do his vocals, right-hand man Garry Shider went to grab him from the hotel over the road.

“George came running in there, thinking his career was over,” recalled his late lieutenant. “‘Gimme a track, gimme a track!’ We had ‘Atomic Dog’ up, with no drums. All we had was all this backward shit in it. George put on the headphones. First time he heard it, you could see his expression: ‘Oh Lord, I don’t understand this music!’ So he started out, ‘Life on all fours, when you’re out there on the street...’.”

David Spradley adds: “He had just gotten through really wearing out the blow or whatever he was doing at the time. He couldn’t find the downbeat. He couldn’t find the microphone either; we had to show him where the mic was, then he went ahead and did it. George laid the lyrics down as you hear them on the record. Then Garry threw a couple of the backgrounds — ‘A-to-mic dooog’...”.

When George returned next day asking for his part to be fixed, Garry said the track was finished, telling him: “We done sang all over you!” After the initial trauma, George came to love the way he’d been inadvertently plonked at the forefront of a cutting-edge movement and ‘Atomic Dog’ now stands as one of the pioneering electronic tracks of the '80s.

PRINCE

George’s Capitol stint saw three more albums ('You Shouldn’t-Nuf Bit Fish', 'Urban Dancefloor Guerillas' and 1985’s 'Some Of My Best Jokes Are Friends', whose booming drum machines and period synths came courtesy of collaborators including electronic boffin Thomas Dolby and Tackhead’s Doug Wimbish). George then fell into a fallow, financially-beleaguered stretch which was rescued by Prince, who he says he called and said, “Yo, bro. We need to get some funk out there”. It’s also been said that Prince called George to sign to his Paisley Park label, eager to repay some of the debt he owed for the inspiration he got from P-Funk shows.

George released 'The Cinderella Theory' in August 1989 (on which Public Enemy‘s Flavor Flav and Chuck D acknowledged their own debt to P-Funk by guesting on 'Tweakin''). This led to this writer's first meeting with George, in June 1989 in an office at Warner Brothers’ New York HQ.

It was a relatively cool afternoon in the city but George warmed up rapidly as he gleefully revisited his vast back catalogue, gushed about his comeback album and expounded about the hip-hop movement which had hauled him out of the doldrums with a new profile as Godfather of Funk — and now Rap.

As a fan since 1971, your hack initially had a job convincing himself that the ever-giggling wise man with multi-coloured explosion-in-a-mattress-factory hair extensions sitting there doodling on my albums was Dr Funkenstein himself. Open and articulate with a wicked sense of humour, there was no burnt-out super-fry here, just a long-time musical hero sitting at a glass coffee table in his extra-terrestrial splendour dishing out memories, theories and refreshments.

The main subject on George’s mind that day was the hip-hop revolution which had given his music a new lease of life as his creations were turned into hits for other people. Some, like Public Enemy and De La Soul, paid him credit and dollars (even if they ended up going to the record company rather than George). After James Brown, he was now the second Most Sampled Man In Showbiz, but rapidly overtaking as Schoolly D, Digital Underground, EPMD and LL Cool J dipped into his catalogue.

Eyes twinkling behind big screen shades, he explained: “Rap has really saved The Funk but it’s the DNA for hip-hop. We put our own DJs on the records and that was like the birth of hip-hop. DJs would talk over records in the clubs, that’s how they kept you on the dancefloor. Chuck and Flavor listened to the Parliament live LP from beginning to end, and they've said that. They said I'm their mentor, and that came at a good time because I was giving up. Now I feel so good.

“I don‘t mind if they sample me because I get back more than they do,” George continued. “Like De La Soul. They used 'Knee Deep' and they paid but I get paid in a different way because I know how to appreciate the fact that they used the music. If they're hot with the kids and the kids like them, then they'll like me. Everyone's into the 'One Nation Under A Groove' concept. So I'm glad they sample the shit. Now if I took 'Knee Deep' to the radio stations, they'd tell me it sounds like De La Soul!”

HIP-HOP

George's influence grew to epidemic proportions the following decade after N.W.A. replicated Worrell’s sine wave synth on 1991‘s 'Alwayz Into Somethin'' and P-Funk provided the well-spring for solo spinoffs such as Ice Cube’s 'Bop Gun'. Dr Dre built his gangsta-funk template on P-Funk, matching the 'Mothership Connection [Star Child]'-derived chorus of 'Let Me Ride' on 1992’s genre-defining 'The Chronic' album with a video containing Mothership landing footage. 'Fuck Wit Dre Day (And Everybody’s Celebratin')' alone drew from 'Atomic Dog', 'Knee Deep', 'Funkentelechy', 'The Big Bang Theory' and 'Aquaboogie'.

That album let lazily laconic stoner Snoop Dogg into the world to become one of hip-hop’s biggest selling rappers with 1993’s 'Doggystyle', Dre building his multi-million-selling debut single 'Who Am I? (What’s My Name)' on 'Knee Deep', 'Atomic Dog' and 'Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker)'. George appeared in the composing credits and appeared on the album’s later-released title track. And so it went on for the new godfather, but Dre’s the one who recently announced he’s become a billionaire.

TECHNO

The P-Funk aftershock also famously resonated to seismic effect in Detroit that decade, Derrick May famously describing techno as being “a complete mistake... like George Clinton and Kraftwerk caught in an elevator, with only a sequencer to keep them company”.

Like previous musical movements which had gestated in Detroit, techno reflected what was going on in the Motor City at the time. By the early '80s, the previously omnipotent auto industry had pretty much evaporated, accompanied by paranoid white flight to the safer suburbs, leaving the city to rot. The desolate blocks, dangerous streets and ruins of the old factories inspired May and his friends Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson to produce their new form of electronic inner city blues.

Like many other Detroit music fans, Atkins first heard Parliament-Funkadelic on Charles 'The Electrifying Mojo' Johnson's Midnight Funk Association radio shows, which ran from 1977 until the mid-eighties. Advertised as 'The Landing Of The Mothership', Mojo mixed P-Funk, Kraftwerk and anyone from Hendrix and Prince to new-wave bands such as the B-52s.

Atkins still speaks of the shows in hushed tones, crediting hearing Parliament-Funkadelic as the epiphany which got him trying to play funk on synthesisers. “'Flashlight' was the one,” Atkins said. “That was the track which took me right over the edge and changed everything. By then Parliament and Funkadelic were using synths on a lot of their tracks and I was right along there with them. Then came 'One Nation Under A Groove', 'Knee Deep'... This was what I was listening to in high school — and it changed my life.”

In 1983, Atkins formed Cybotron with Rick Davis, recording seminal electronic instrumental 'Clear'. This act morphed into Model 500, who brought in electro and space sensibilities derived from P-Funk and Bambaataa on 1985’s 'No UFOs' — arguably the first techno track.

Juan started his Metroplex label, while May and Saunderson formed their Transmat and KMS imprints after being profoundly influenced by the anarchic disco mutation called house gestating in nearby Chicago. Detroit’s new musical underground seemed to echo the ghosts of the vanished auto plant machines with piledriving beats washed in unearthly synth melodies. Further names, including Underground Resistance, Robert Hood and Carl Craig have also credited P-Funk’s part in the music which became a global phenomenon because, as they stress, what sets Detroit techno apart from countless copyists is it never loses The Funk.

NASTY DOG

At that first meeting 25 years ago, this writer asked George what the Cinderella Theory was. He explained, “It's like a concept; how I love the pop star philosophy, all the high marketing and publicity... then after 12 o'clock I turn into the funky nasty dude. I'm on a mission. I agree to be the pop star for publicity reasons. But after midnight I turn into a nasty dog.”

A quarter century later and we're sitting with George again, this time by the swimming pool of Ibiza’s opulent Hard Rock Hotel against a backdrop of Mediterranean waves rather than New York street bustle (although that’s an even bigger contrast to the Primal Scream dressing room I last saw him a few years ago). He’s here to make his somewhat surreal appearance as top-of-the-bill keynote speaker at this year’s International Music Summit, invited as a founding father of the dance music he helped formulate and take to the world stage, which is now being celebrated and discussed.

Now approaching his 73rd birthday, the nasty dog has inevitably mellowed and on a different kind of mission to reclaim those tracks he was flattered to see hijacked 25 years ago (although still cackling “I’m a dog” as his parting shot). Clinton will still trot out the old stories on demand and, if circumstances had allowed, the new album he’s about to release.

Although George is eager to place himself in the thick of the EDM doing massive business in the US, he is already validated by that afore-mentioned techno connection as those on the island with an ear to what’s going on beyond the Vegas-style excesses of the Justin Bieber-style cabarets propagated by the squeaky clean likes of Avicii are citing techno as the sound of the summer, with DC10, Sven Vath’s Cocoon and Richie Hawtin’s ENTER set to provide the most happening nights.

Finally appearing at the tail-end of the event, George regales a small but rapt crowd with his repertoire of outrageous memories and funk-related sound-bites. Asked whether he got paid for the samples which built hip-hop, he confesses: “No, that’s what made me start doing drugs! It took me 72 years to find that out. I realised that I’m not even high. Now it’s publishers, record companies... Instead of a drug habit, I got a lawyer habit.”

While many of his keynote questions predictably honed in on making albums on acid and taking the stage in a fully-formed Mothership, George was eager to stress his ability to be relevant to today’s dance scene, declaring at various times: “This is the 21st century. We’ve been looking forward to the 21st century ever since 1968 when 2001: A Space Odyssey came out... You knew the 21st century was gonna bring all kinds of everything... The electronic age is the new sound. We might as well get used to it. If it makes you shake your booty, you got funk in it. That’s how I look at it. If I see people dancing, then some funk must be around... Straight through from funk to disco to hip-hop, techno, rave, all of it is dance music. The people are dancing. That’s what the world’s about. I ain’t got no problem with it. Whatever’s happening, I’ll learn it.”

To underline his point, George previewed two tracks he’d recently recorded with Boston producers Soul Clap, one boasting old mucker Sly Stone, the other a shined-up stab at 'Get Lucky'-style EDM crossover.

Along with court appearances and a relentless gigging schedule, George is entering his 73rd year with a flurry of activity, including a reality TV show called The Clintons, new album and his autobiography (part memoir, part courtroom accounts), snappily titled Brothers Be Like ‘George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kind Of Hard On You?’: A Memoir By George Clinton. Released (also under that title) on his C Kunspyruhzy label, the 33-track album includes tracks recorded earlier in the year at London’s Metropolis Studios, guests including Joss Stone, Boy George and Rudimental, along with Soul Clap, whose album will share their collaborations.

In 2014, George Clinton really has nothing to prove except gaining back his past achievements on paper. His legacy is so immense he doesn’t have to bow to EDM or even the Nile Rodgers route of mainstream awards acceptance, although deserves them just as much. What Clinton has contributed to the music people dance to today is beyond earthy comprehension, so let’s just say good luck to him in his ongoing struggles and hope he can soon take time to rest on those mighty laurels, safe in the knowledge he put one world under a groove.

Kris Needs’ P-Funk tome George Clinton & The Cosmic Odyssey Of The P-Funk Empire, from which parts of this piece are adapted, is out soon on Omnibus Press.

WORDS: Kris Needs