SIMIAN MOBILE DISCO: BRAVE NEW WORLD

DJ Mag chats to James Ford about making the new LP, aliens, cowboy ghost towns, destruction and drones...

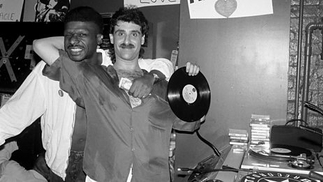

When the Klaxons joked that their producer, James Ford, communicated with aliens through his hair, they weren’t only paying tribute to his curly black locks.

Ford and his electronic other half, Jas Shaw (who together make up Simian Mobile Disco), have always possessed something of the ‘other’ and ‘outer’ about them. Despite being music insiders, with world-class collaborators beating a path to their door, they fit comfortably within the outsider traditions of electronic music.

“We’ve alway been slightly contrary,” admits James Ford. “Whenever we do something, whether it goes well or badly, we want to do the opposite next time. I can’t see the point in making the same album over and over, it’s really boring.”

Boring definitely isn’t part of SMD’s game-plan. The last time this writer saw James we were staggering across a lightning-whipped Latitude festival, where he’d been playing tent-thrashing techno. A few weeks before that I’d caught them both unveiling their new album, 'Whorl', with a live show that, alongside Roll the Dice, was one of the defining sets of Sonar 2014. Today James is in his East London home prepping for tomorrow’s gig in New Yorks’ Museum of Modern Art. There’s not much time for being “bored”.

DESERT ANARCHY

'Whorl', their fifth LP, is their most experimental and exciting yet. Recorded in the middle of the Californian desert, in a squatter community housed in an abandoned cowboy filmset, 'Whorl’s shot through with references to Delia Derbyshire, Raymond Scott, krautrock and other pioneers of electronic music.

But it’s also a fiercely contemporary album, picking up on the immersive zeitgeist present in recent outings by James Holden, Roll the Dice, Luke Abbott and others.'Whorl' questions the accepted structures of electronic club music. It also dismantles SMD’s own norms. “This was very deliberately different,” James happily admits, “it was manufactured to be different.

“We’d got to the end of a run of live shows [and] recorded a Iive album, which documented where the live show was up to. It seemed like the natural point to pull apart the whole system we’d built up for playing live. So we pulled it apart and started afresh... which kind of means we can’t play any of the old stuff anymore,” he laughs.

Anarchist philosopher Mikhail Bakunin argued that destruction is a creative urge, and SMD’s act of apparent nihilism led to a re-evaluation of what they were doing. They hit on the idea of uniting their live shows with their studio work, bringing the two elements together into one system. “It was exciting; an exact halfway between the studio and the live performance. So we set about building a system that involved a modular synthesiser and a sequencer each, and a mixing desk.

“We pulled the rug away from any kind of playback, so everything is generated live, every sound made from a module or group of modules, a voice. So we built the system and it transpired it was really portable. Basically we could carry it in a couple of suitcases, and a mixing desk. We didn’t have to be in the studio to record. We could be anywhere!”

In a moment of cosmic synchronicity, the duo received an offer to play in Joshua Tree, California. “It seemed quite serendipitous — a good opportunity to get out of the London studio and give us something to aim for.

“We had the [portable] studio, a gig and a month in-between — so we wrote the album with the gig in mind.”

Re-working the material they'd been playing around with while developing the live-come-studio set-up, the duo created an album they thought would work as a live set.

And after recording a basic version of the set as an ‘aide-memoir’, they set-off to an isolated holiday house in the middle of Joshua Tree National Park.

“We were there a week, rehearsing and mucking about in this amazing place called Boulder House. You can hardly see any civilisation, so we did a little set-up on the rocks one day, filmed it and did a little performance to nobody apart from some geckos. That was really special. It feels like you’re on the moon. You can’t see anything man-made and there’s some quite complex technology in front of you — like something out of a sc-fi movie.”

STRANGE LIFE

The gig itself was at Pappy and Harriet’s, a venue James had come to know while producing the Arctic Monkeys at Rancho de La Luna — a band he’s produced so many times he’s been dubbed the fifth monkey. “I love Joshua Tree as a place. It’s got the weird bits of America that I’m fascinated by. The hippy, alien-chasing [bits]... a lot of people go there to drop out and live this strange life in the middle of the rocks. So we jumped at the chance. We did the gig at Pappy and Harriet’s in front of 900 people. Locals, some weird biker-types...”

The crowd also consisted of friends and music industry types who’d tripped in from LA. “We played outside and recorded it at night. A lot of people came from LA — it's quite a big ask, to ask people to come into the middle of nowhere and hear an album they haven’t heard before.

But they had a really good reaction. People responded to the fact we were recording it and so their participation kind of changed the decisions we made and became part of the record.”

The atmosphere of the town itself no doubt also fed into the recording. Pioneer Town had been built for a Roy Rogers film in the 1940s. But the abandoned set became a self-fulfilling prophesy, and people started living in trailers behind the building facades. “It looks like you're in a spaghetti western and there’s nothing else around. Pappy and Harriet’s is the saloon at the end of the town.”

Armed with the recording from California and the earlier version from London, James and Jas set about mixing down an LP. “We didn’t want a live album, (they’d just done one of those). We didn’t want crowd noises, we wanted it to feel like a real album. But we wanted it to have the freedom, the looseness, the happy accidents you get from doing something live.”

The process they’d ended-up choosing had more in common with the touring rock bands of the late 1960s than the way most electronic producers work. It’s a comparison James relishes. “There’s always that thing that Cream’s 'Disraeli Gears' was recorded in a weekend. The same with The Beatles' early albums. But that was only because there was a system in place — great engineers that recorded people live.

It was a case of documenting a moment in time, rather than creating something in the studio.

“As a producer that’s an idea you come across a lot with live bands. But electronic music is usually [made] in the studio, often by pushing blocks around a screen. So to try and do a performance and document a moment in time, rather than labour over a computer, is a very different way of recording. The idea of doing that with electronics really appealed.”

ACTION/REACTION

Another driving force behind the new LP was a reaction, in common with a number of producers, against the growth of increasingly formulaic electronic music. “A laptop allows you to be pretty lazy. You can open Logic and Ableton and there’s loads of shit trance loops and you can probably bang together a track. But making something that stands above that is still really hard.”

Part of the driving force behind the destruction of their usual set-up was the desire to make it hard, to bypass the easy routes. “Me and Jas have been making music together a long time. We have ways of doing things and work quickly. So making things difficult is a good thing. It took away tricks we know will work — like, ‘the Juno will do this really well’ or ‘the 808 will do that’. We took all those things away.”

SMD’s break away from electronic music’s conventional recording platforms has given 'Whorl' a strikingly fresh tone. This itself feels like a comment on blandness in music production — as if new technology has limited people’s horizons, and made all music sound similar. “It’s hard to explain why that’s happened,” James ponders. “You would think it would get broader. Maybe the issue is that technology allows you to take the easy route.

“I was talking to Graham [Massey] from 808 State, to get some parts off him to remix one of his early tracks. He said ‘there aren’t any parts!’. The drum machine was slave to the tape machine and that was going down onto the master tape, so they didn’t record the drum parts. It was much harder then. The fact it’s easy to control every aspect of music on a computer means things become much more homogenous.”

The trend towards increasingly homogenous music is something that James frequently addresses as a band producer, often recording onto tape, rather than a computer.

“My thing about recording to tape isn’t that it sounds better.

It makes you record in a different way. You have to make all the decisions upfront, you can’t go back and fix anything, it has to be right and then you record it. And if it’s not right, you’re faced with the decision of re-recording and going over it or doing a weird fix. Like, if the drums are really quiet, put a big tambourine over it. That’s why a lot of Motown tracks have a big tambourine.”

When James produced Alex Turner’s soundtrack to the film Submarine, he used a mono two-track studio that gave the music an intimate, pared-back fragility. 'Whorl' feels like the logical conclusion of that process transferred onto SMD.

“I often get asked and I never really thought about it connecting before. I don’t often see the links between recording with the Arctics and recording with Simian. But the example of 'Submarine', and that recording experience, definitely informed how I do things. That never really affected Simian before, but this is our version of that.

“To all purposes we could have recorded this album onto tape. The approach is the same. It’s good old-fashioned preproduction.”

Conversely, one of the things James has taken from SMD into his role as a band producer is an appreciation of the way technology and methodology shape the artistic process.

“It’s fundamental to the decisions you make,” he explains. “The way Logic or Ableton works dictates the decisions you make about creative things.”

Software, he argues, can determine whether you change the speed of a loop, depending on how easy certain functions are to use. This changes the artistic result. “It could be as basic as writing on a bass guitar or writing on a six-string guitar. It’s going to make you do a different thing.”

WEIGHT OF EXPECTATION

SMD are also releasing 'Whorl' on a new label, picking the unlikely choice of the US label Anti — more commonly associated with Tom Waits and Kate Boosh. “It's an odd label for us to be on,” agrees James. “But they’ve been involved since before we started [recording], so they didn’t know what they were going to get. I think they were pleasantly surprised because we sold it being weirder than it turned out.”

Apart from persuading a label to sign them without hearing their LP, SMD also had to think about how their fan-base would react. At one point they even considered changing their name for the project. “There’s a weight of expectation whether we like it or not, and we have to be careful with the gigs we choose with this. We can’t easily play much old stuff. We don’t have any facility to play any vocals. So if we did a big festival, there would definitely be people saying ‘Why didn’t you play anything we knew?’ Which always comes across as wanky. But the reality is we just can’t!”

As a reaction to the current climate in electronic music, 'Whorl' is a product of its time. But it is also a personal reflection on references that stretch back across electronic music’s history. “We love all that [krautrock] stuff, Delia Derbyshire, Raymond Scott and early Warp and we’re really into the new Holden record and Luke Abbott. ['Whorl'] feels like a fairly honest representation of our music taste at this point.”

It’s also clear from the work of artists such as Holden, Abbott, Roll the Dice and others, the issues 'Whorl' addresses are current topics in electronic music. “I went to see Charles Cohen recently,” agrees James, “and there were definitely lots of people there who are in that world. Like you say, it’s not out of the blue. There is definitely something around. It’s probably a reaction to how crass and dumb a lot of dance music has become — especially in America. It's almost like remembering why you love it in the first place

“Its happening in America 15 years after it happened here. When you had the first wave of superstar DJs and super clubs, straight after that you had Autechre and all those sorts of things. This is another ripple in the pond of that same thing.”