After Astroworld, what is being done to stop crowd crushes from happening again?

After the tragic events of Astroworld Festival last year, Will Pritchard examines the science, politics and history of crowd crushes at mass gatherings, and asks experts how organisers can make future large music events safer

There are few gulfs like that between the throes of a party and the aftermath of a tragedy. It’s an abyss Keith Still is familiar with. Last November, he found himself there once more, as the catastrophic events of Travis Scott’s Astroworld festival unfolded in Houston, Texas. In the days that followed, the death toll hit double figures. Ezra Blount, the day’s youngest victim, will never reach that in age. He was nine years old.

“I just thought, ‘Oh god, not again’,” says Still, a professor of crowd science, whose gentle Scots thrum belies the disasters he’s paid witness to over a 32-year career. Still’s work is a balance of prevention and post-mortem: he runs training courses in the hope that, some day, there won’t be another aftermath — discarded shoes, spent medical supplies, flattened ground — that requires him as a witness. Every death reflects a failing. “It’s a repeating pattern,” he says, sounding weary and furious. “There’s a DNA to accidents, and it’s typically the same problems over and over again. It’s a lack of understanding of the risks associated with crowded spaces. If it was predictable, it should have been preventable.”

While many festivals chose not to risk cancellation in 2021, postponing their planned events instead, this summer looks set for a full return of festivities. Last year, the prospect of lifted restrictions triggered a 600% rise in traffic to Ticketmaster. Summer 2022’s crowds will be more swollen, anxious and unseasoned than perhaps any before them. Astroworld’s shadow lingers, reminding organisers of what’s at stake each time they gather people in a park, field or arena.

Since the last ambulance departed the scene in Houston, Still has been sitting in evidence sessions and analysis meetings. Almost 400 lawsuits involving more than 2,800 plaintiffs swirl over Travis Scott, Live Nation, ScoreMore and HCSCC, the organisation responsible for managing NRG Park, where the event took place. As legal mechanisms whir into action, victims seek justice. But they, and others, also seek answers: why does this keep happening? And what is being done to stop it?

Between 1999 and 2015, there were more than 44 incidents globally in which a crush killed 10 or more people. In the six years since, there have been another 21. Around 20% of these most recent mass death events occurred at music shows; others were at sports matches, religious gatherings or, less commonly, protests and public funerals.

The first recorded crush with mass casualties at a music show happened in 1979. Eleven fans of British rock band The Who had the breath pushed out of them as crowds piled up against shuttered doors at the ill-prepared Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati, Ohio. Five years earlier, 14-year-old Bernadette Whelan became an unwanted footnote in history after being crushed to death at a David Cassidy concert in White City, London — the first recorded fatality of its kind at a British pop concert. Decades passed before another major musical incident, but the death of nine Pearl Jam fans in a crush at Denmark’s rain-soaked Roskilde festival in June 2000 confirmed that music shows aren’t immune to tragedy. The Roskilde deaths were all ruled accidental, but the speed of response — to pull people from the pile — was criticised.

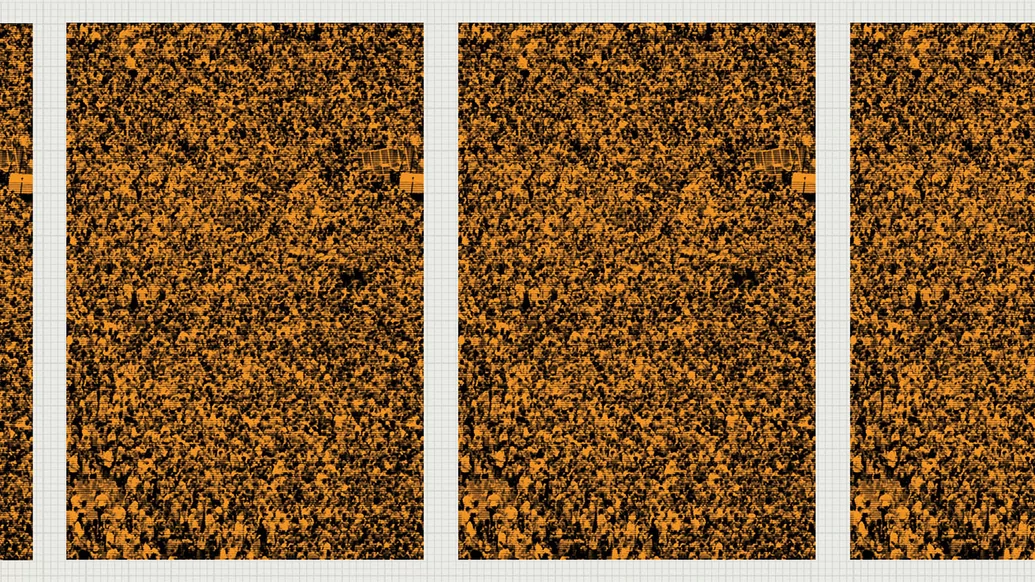

In the years since, concerts have multiplied and music festivals have become a ubiquitous fixture of the Great British Summer. A typical year in the UK sees as many as 975 music festivals. In 2019, the most recent ‘normal’ year for mass gatherings, 5.2 million people attended music festivals in the UK — 300,000 more than the year before. In Europe, countries such as Croatia, Malta and Spain have established themselves as popular festival destinations, while Serbia’s EXIT has been running for more than 20 years and boasts weekend crowds of 180,000 people. In America, there are behemoths of bacchanal: Electric Daisy Carnival, Ultra and Electric Zoo. More than 30 million people attend US music festivals each year. Dance music — once relegated to side stages at rock-oriented events — is increasingly a main draw.

Simultaneously, the world has become more urbanised, and economies more orbital of ‘experiences’ that can be bought, sold and ‘shared’ online. Eighty-six percent of large festivals in the US take place in metro areas, suggesting that festivals have become as much about easy access and scalable, price-gouging amenities as free-spirited living. Chunks of public parks in UK cities are increasingly given over to hosting private festival sites — even if the value they offer cash-strapped councils is seemingly negligible. Space in cities comes at a premium, so festivals are happening in increasingly tight spaces by necessity and design.

The boom in the experience economy has come with its own cabal of well-meaning chancers — and poor execution. Bloc 2012 was an early canary at the coalface of city festival profiteering: an outing so chaotic (queues, crushes, cancelled mid-way through the first night) that the feted multimillion-pound “arts quarter” it took place in, London Pleasure Gardens, went bust just one month after opening.

Disgruntled and dehydrated crowds snaking in hours-long queues have become a fixture of some city festivals, with would-be revellers broadcasting their woes to social media. In 2021, it was YAM on Clapham Common; two years before that, at We Are FSTVL, organisers ran out of wristbands and barriers were knocked down. 2017 was a vintage year for cock-ups: Liverpool’s Hope & Glory buckled under overcrowding before it got started; Sunfall in London’s Brockwell Park was an odyssey of queues; faulty ticket-scanners at Boomtown resulted in seven-hour delays. No one died at these events. Their smaller failings became the ephemera of a drunken, sunlit summer.

When crowd crushes are discussed today, it’s a handful of cases that shape the conversation. There’s the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, and the battle for justice fought by the families of its 97 victims; there’s the 2010 Love Parade, at which 21 people died and for whom no justice has been served; and then the sheer, catastrophic scale of the 2015 Hajj pilgrimage, in which at least 2,400 people were crushed to death in Mina, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Astroworld, unique for the real-time detail in which the tragedy unfolded online if not the controversy that now engulfs it, will no doubt join that list. But gazing over history in this way can give these events a sense of novelty, inevitability or even rarity that’s unjustified.

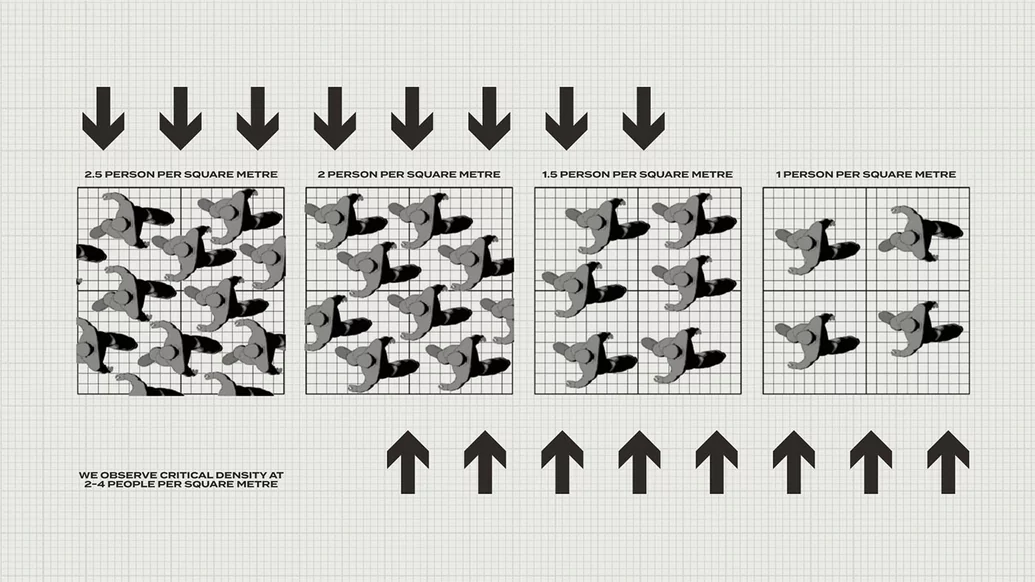

People who die in crowds tend to suffocate. Sometimes they’re held standing by the crush of bodies and barriers that pen them in and push the air from their lungs. Broken bones and boot-marks on faces are the details media reports swarm on, but the reality is less graphic. All 10 Astroworld deaths were recorded as resulting from “compression asphyxia”. It was the same in Cincinnati, at Love Parade, and for 93 of the 97 eventual casualties at Hillsborough. It’s a question of density, of room to breathe.

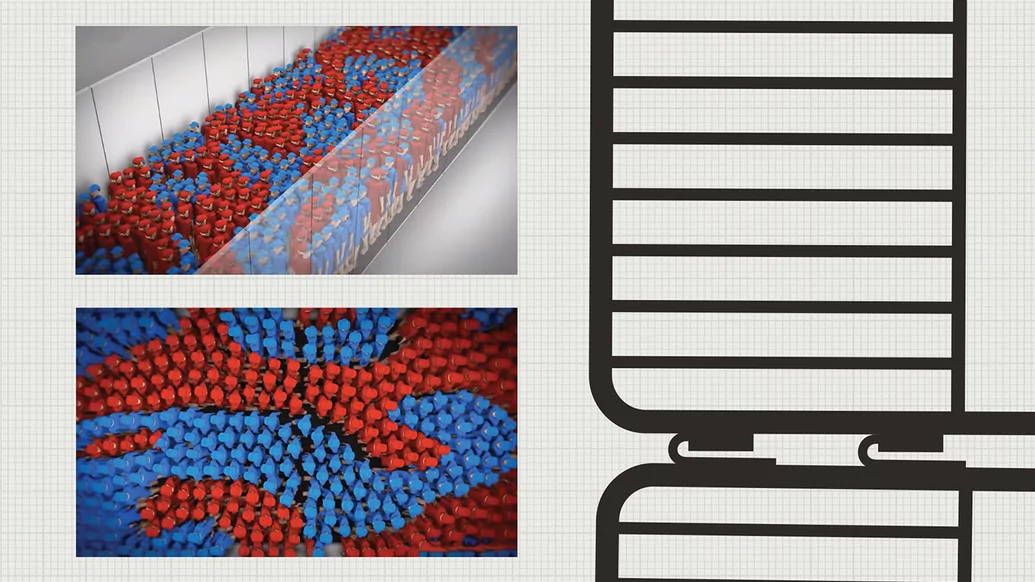

“It’s not the number of people, it’s the number of people in the area,” says Still. When people in a moving crowd become packed together too closely — anything above six people per square metre — they lose control over their movements, behaving instead like a fluid, shifting en masse. Pressure waves course through. If someone loses their footing, they’re either held aloft by the bodies compressed against them, soles sweeping the ground, or they go down, and more people fall into the void they create — piling on top of one another. Gravity joins the crush.

Still demonstrates this crush effect with lo-fi animations, featuring spherical attendees heaping up on each other. It’s almost absurdly comic — like some of the surreal, poorly made 3D animations that draw cult followings on YouTube — until you consider what each blob represents. The simulations are engrossing: slip down the rabbit hole and you stop seeing blobs, and instead start spotting the bottlenecks, tight corners and limited exits that will, if left unaltered, soon be the site of a pixelated tragedy.

While food and drink provisions and demountable structures (like stages and tents) at mass events are covered by strict licences, no such rules govern crowd safety. “A crowd management plan? Any Tom, Dick or Harriet can draw that up,” says Still, “you don’t need to be qualified. And that’s the crux of the problem: without having an accredited standard for a safety function — crowd management — without any formal qualifications required to do that, then it’s always going to be the weak link in the chain.”

The majority of uniformed staff that people encounter at barriers and entry-points at festivals are stewards, not security. While security staff in the UK are legally required to hold an SIA Licence — which involves training around conflict management and physical intervention, multiple-choice exams and a practical assessment — requirements for stewards are far less stringent. Stewards are encouraged to hold a level 2 NVQ qualification in Spectator Safety, but there’s no legal requirement to do so; event staffing companies can opt to offer their own training instead. Pay for stewards hovers around minimum wage.

“It was one of the worst jobs I’ve ever had,” one former steward tells DJ Mag. “Possibly one of the most unsafe work environments I’ve experienced: an army of teenagers meant to crowd manage tens of thousands of people, working 14-hour shifts with hardly any breaks.” They were hired through the JobCentre by an established security firm to staff events at the 5,000-capacity Brixton Academy, and Lovebox Festival, which hosts around 50,000 people each summer. Training was minimal, and largely unmemorable but for a few details.

“In training they basically advocate violence by saying that the most important person to protect is yourself, and that means you can do whatever you want if you feel threatened,” says the former contractor. (Both Brixton Academy and Lovebox have since entered new contracts with different contractors.)

By the time stewards are hired, they’re often at the end of a long line of cost-cutting that’s taken in the amount of space paid for, the robustness of the fencing around the site and more. But the solution isn’t necessarily in hiring SIA-wielding bruisers either. “There’s this dangerous assumption that just because I might have a doorman’s licence, that somehow makes me qualified to understand crowd dynamics. It doesn’t,” says Still, brusquely. It remains up to organisers to balance safety and cost. “And, you know, that balancing act is something that shouldn’t be left to an accountant,” says Still. “Safety makes no profit.”

There’s an obvious risk to this kind of cost-cutting: not just in minimising the chance of accidents happening, but in being able to provide a swift, safe response if things do go wrong. At Lovebox, the former steward says, “People were breaking in all over the gaff and we were just like: ‘please don’t’.” It’s hard to expect poorly trained teenagers on roughly £7 an hour to do much more. Operating in increasingly cramped parks and industrial spaces, the job isn’t getting any easier or more forgiving.

“It’s not rocket science. Know your performer, know your crowd, design your site and get professionals in to do it, rather than taking a guess at it and hope that things don’t go wrong on the day” — Keith Still, professor of crowd science

People don’t always die in crushes. “Look at the history globally of mass fatalities and major injuries,” says Still, “it’s only fatalities that get to the headlines. But underneath, there’s all the civil litigation for people who’ve been injured at events that never gets reported.” Most of these cases are settled out of court, Still says, making it harder for experts like him to access the evidence. This contributes to muddy popular conceptions of how these tragedies happen and what causes them. Muddiest and most popular of all is that the crowd is to blame.

Headline writers like to describe crowd crushes as “stampedes” and “mass panics”. It’s a misconception that troubles Clifford Stott. He’s a professor of social psychology at Keele University, and a specialist in the psychology of crowds, group identity and football hooliganism. “These narratives are based on outdated, what we call ‘classical theories’ of the crowd,” he says, punctuating each point with a prod of the table: “And they have no basis in evidence.”

Indeed, the evidence points in the opposite direction. Following the deaths at Love Parade, socio-physicist Dirk Helbing’s report concluded that mass panic was not the main cause. Inaccurate and sensationalised descriptions hinder attempts to understand what causes these events and how they unfold. The 2010 Love Parade is still referred to as a stampede.

“People don’t die because they panic,” says Professor Still, “they panic because they’re dying.” Organisers and authorities contribute to the fog, either by pushing the same false narratives or by failing to correct them. “The implicit message is, ‘It wasn’t our fault, it was theirs’,” says Clifford Stott, prodding again: “‘The blame for this lies in the crowd’.”

The image that’s conjured, he says, is of the pathological crowd; an amassing that causes people to lose their rationality, become uncontrollable and dangerous. It follows an authoritarian logic — one borne out in the UK’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, and the Act’s uglier, more brutal cousin currently making its way through Parliament, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill — that it would simply be easier if crowds never formed.

For victims, there’s limited legal recourse. On 26th July 2007, the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 came into law in the UK. It was introduced following the explosion of the Piper Alpha oil rig in 1988 and a blaze at London’s Kings Cross tube station in the previous year. The law is used to prosecute organisations when it can be proven that their management has caused a person’s death. It hangs on the organisation’s duty of care, whether that be for a window cleaner in a rig 15 storeys up, or a music fan moshing and dancing in a field. But the stringency of the law’s conditions has proven it toothless. There have been fewer than 30 convictions since it came into force in 2008.

The day after the final Love Parade, the police, Duisburg city officials and Rainer Schaller — the multimillionaire German who bought the rights to Love Parade in 2006, using the gathering as a marketing vehicle for his chain of cheap gyms — took turns at passing the buck. Commercial organisations such as promoters, venue owners and security companies can rally and defend their own interests with a cohesion that the crowd — once swaying and tumbling together, now broken into lone voices — is rarely able to achieve, save through the complexities of class action lawsuits. (Responses to Astroworld have, so far, followed a similar playbook.)

This pattern has serious consequences. The passage of time doesn’t bring any clarity, so the facts become harder to discern, responsibility more difficult to assign and mistakes more easily repeated. In the Love Parade trial, charges against six Duisburg city officials and one event organiser from Schaller’s Lopavent company were dropped in 2019. The remaining three Lopavent employees escaped a verdict when the case petered out a year later. Even without Covid-19 shuttering courtrooms, hastening the deadline for the statute of limitations, this might have happened anyway: the prosecution had openly admitted their struggle to pinpoint responsibility for the deaths.

The process of holding those responsible accountable is slow and fraught, which in turn makes more concrete, industry-wide changes difficult. History, and the experience of sports and religious crowds, suggests that a large-scale tragedy has to occur for safety measures to be backed with legislation, or for guidance to be enshrined in law — giving victims a direct route to justice, and organisers an incentive beyond their bottom line to get things right and avoid tragedy in the first place.

Dušan Kovačević describes his organisation as a “festival factory”. EXIT now puts on nine festivals in seven countries every year, and employs 100 full-time staff, including safety and crowd management experts. The company’s flagship festival — and Europe’s biggest — is its namesake event, held in Serbia’s second city, Novi Sad, every July. The decision to run the festival inside the Petrovaradin Fortress — the history of which stretches back to the Palaeolithic age; its modern form finalised in the 18th century — has forced Kovačević and co to find safe ways of partying among the ancient walls and trenches.

The fortress setting brings its own difficulties, but in more than 20 years of putting on events, Kovačević says they’ve never had a serious safety incident occur inside the festival site. (He specifies “inside”, and therefore within the festival’s jurisdiction: a 22-year old man died in 2009 after falling from the fortress walls; the year before, a 28-year old woman was killed by a falling tree brought down by high winds.)

Kovačević credits this record to a combination of values and experience. They cap the space at 50,000 attendees (“We could go to 60,000 and it probably would be OK,” he says, “but we don’t risk that”) and programme the stages to ensure an even spread. If there’s an act they know will draw a big crowd, then they force a clash: “We put another headliner on in another arena, and make people choose,” says Kovačević, disarmingly matter-of-fact. “It seems complicated, but it’s probably now in our DNA,” he says. The ability to carry this knowledge and experience forward from year to year has been crucial; Kovačević suggests that new festivals should have legal obligations to hire people with “at least 5-10 years” of experience in safety and crowd control.

Other big events have gone beyond programming acts as a means of crowd management. The biggest dance music festival in the US, Electric Daisy Carnival, moved to Las Vegas in 2011 following successive years of controversy in Los Angeles (spanning underage attendance, drug death and crowd crushes). In recent years, organisers have wrapped new attractions into the event, including daily opening ceremonies and a fully fitted-out campsite, as a way of staggering entry times, breaking up crowds and keeping people safe. Just as there’s a DNA to accidents, safe shows have their own makeup too. “It’s not rocket science,” says Still: “Know your performer, know your crowd, design your site and get professionals in to do it, rather than taking a guess at it and hope that things don’t go wrong on the day.”

There are obvious, practical things that, Still says, “even a layman could see”: lots of clear and visible signage; a layout without kinks and bottlenecks; plenty of exit points; water stations; ample, well-trained staff. Then things that seem obvious but come with experience (such as Kovačević’s programming) and those that are led by values not value (like purposefully underselling tickets). Then, more technical stuff: keeping bodies at four per square metre or below. These are things that can be regulated, enshrined in legislation that holds organisations accountable.

Finally, there are things that are harder to pin down with a figure. These involve harnessing the power of the crowd, and its collective identity. Dr Anne Templeton, lecturer in social psychology at the University of Edinburgh, suggests emphasising the group’s core values. She notes T In The Park’s ‘Citizen T’ initiative, which the festival uses to improve its green credentials by encouraging environmentally friendly, sustainable behaviours. It’s more about encouraging self-regulation and light-touch management than exerting control. Organisers, performers and stewards all have a part to play in this.

Clifford Stott agrees. “In my experience of big music events, it’s that solidarity, that sense of empowerment, that sense of freedom that I can find in a crowd that I find really compelling,” he says. “Part of that is about escaping control. It’s about escaping the control of the state, of the police, of the stewards, of the bouncers and finding a place where we can have solidarity and agency. And when you think back to the evolution of house music and the dance culture in the UK, it was very much about that.”

Solutions, then, aren’t simply spelled out in surveillance, security and sanitisation. Answers can be found in events that encourage solidarity too. (And signage, Templeton says — lots of signage.) Keith Still doesn’t want to investigate the death of another nine-year-old. It’s a wish anyone with the requisite power would grant him. But he of all people knows that safety isn’t won with wishful thinking. Without a wider commitment to understanding — and acting on — what underpins these tragedies, it can only be a matter of time before he’s picking over images of bent barriers and crumpled trainers again, wondering what came of their owners.