What is the future of the DAW?

Emerging technology has left the DAW at a crossroads. A combination of legacy code, compatibility restrictions and a user base who expect their favourite tools to remain familiar has left music-making software lacking innovation. As the pandemic, cloud-computing and generative AI shift expectations of how music-making tools should look and feel, Declan McGlynn asks: will the DAW adapt or die?

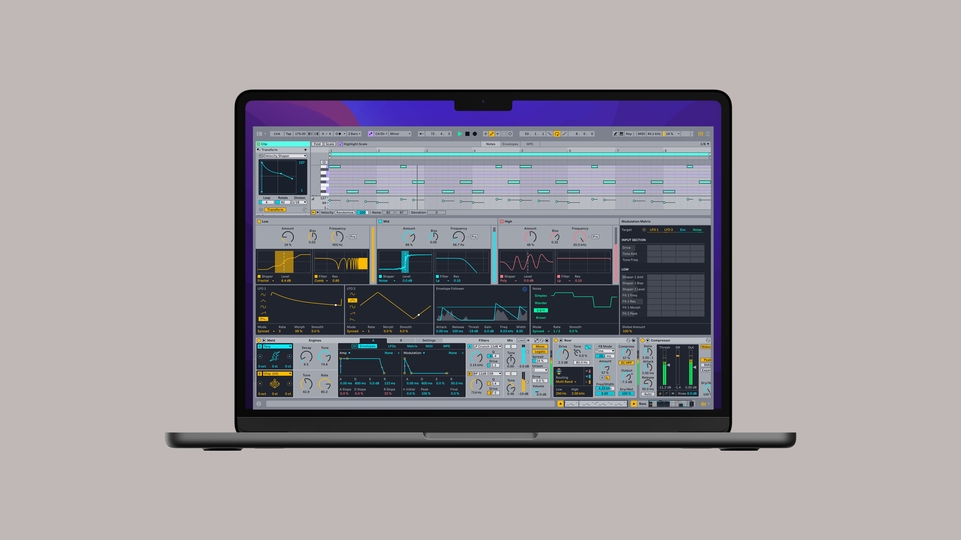

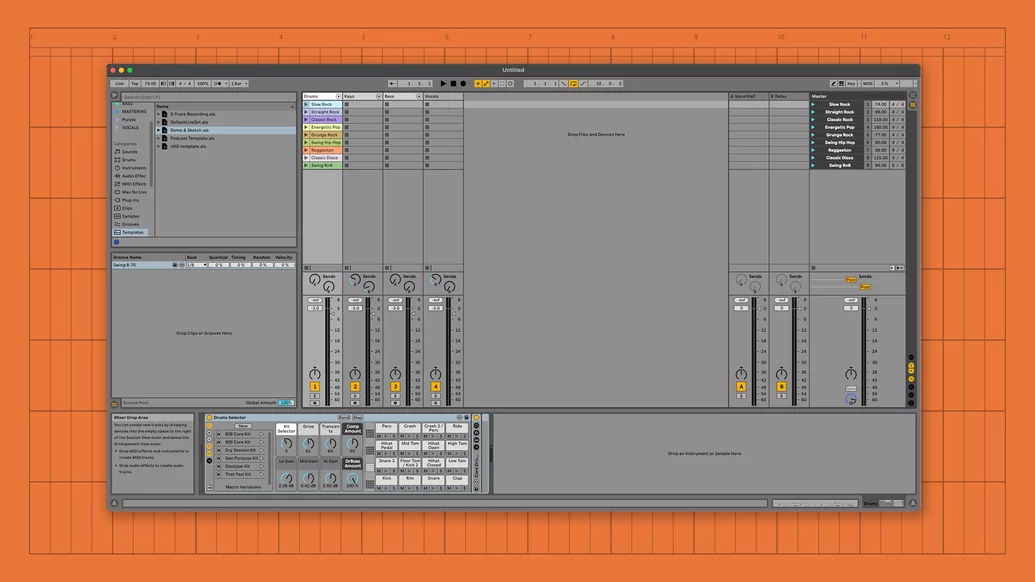

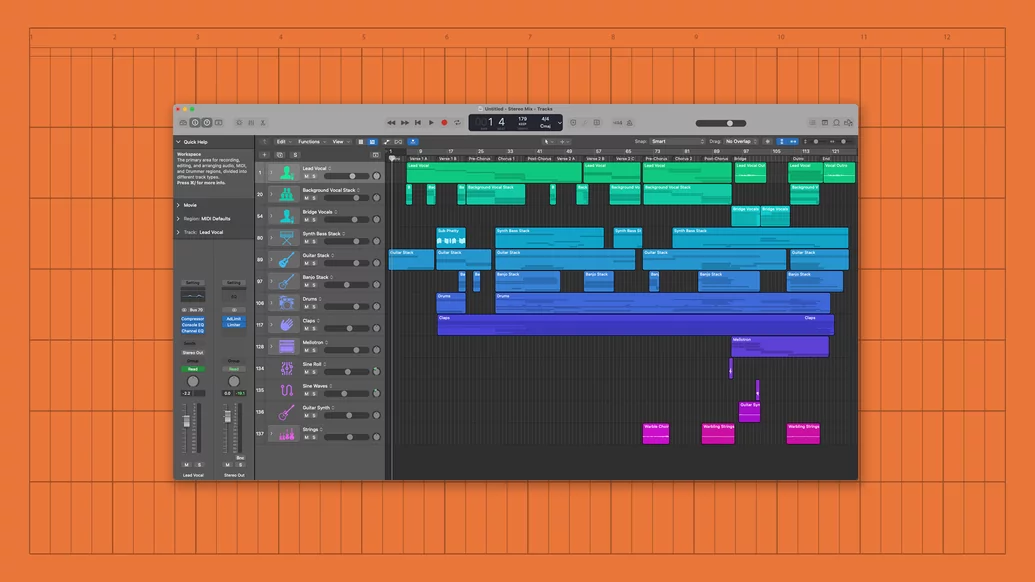

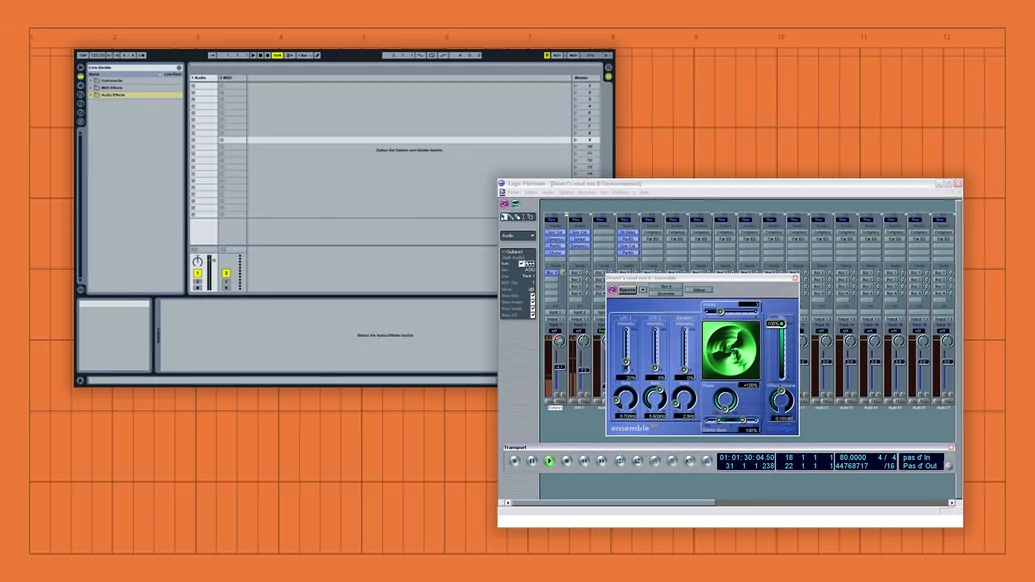

Open a DAW from the year 2000 and it’s highly likely you’ll recognise the vast majority of the features — both functionally and visually — from any DAW you might use today. There’ll be an arrange page from left to right, a MIDI note editor, a browser on the left, a mix window with a row of virtual sliders and input slots for plugins. Of course, the tech powering our fave DAW has drastically evolved since then but, fundamentally, the experience remains almost identical.

DAWs are built on legacy code that can’t easily be pivoted as user expectation adjusts, or new technology arrives. Where DAWs stalled, plugins filled the gap, allowing developers to conceive new ideas to paper over the cracks, while DAWs remained the static, fairly reliable layer underneath. But plugins, too, have become stagnant: even with thousands of VSTs available on the market, with more arriving every month, very few truly innovative ideas are pushed out each year, instead copying existing tools or re-inventing the same analogue-modelled synths and hardware.

That’s not to say every DAW and every plugin are completely lacking in innovation — Ableton, Bitwig and FL Studio, to name only three, are all pushing the boundaries of what’s possible within a DAW infrastructure. But has the rapid rise of generative AI tools left the DAW companies vulnerable? How can they appease their core pro user base who expect familiarity and compatibility, while also adopting ground-breaking AI tools that the next generation of producers will come to expect from their music-making software? Can the DAW really remain offline as the world’s creative tools move to the cloud? Will the DAW remain at the top of the creative food chain? Or has something got to give?

We spoke to a series of experts, from the developers behind the world’s biggest plugins, to the innovators building the future DAWs, to find out where the DAW sits in 2023, how its limitations have held back innovation, and where we go from here.

“The main friction is in the unfortunate legacy codebase of the DAW,” explains Scott Simon, a pro audio consultant who spent a total of 18 years working at iZotope and Waves. “Everybody [working for] the DAW manufacturers knows it — they recognise and feel that friction.” Simon claims DAWs have become Frankenstein-style software, where new features were bolted onto an existing codebase, eventually causing a bottleneck for innovation.

“The DAW has created this fascinating cottage industry that went from zero to $2bn a year of collective stuff that works inside of it,” he explains. “But if you go back 30 years to now, it’s become this house that you’ve built 700 additions to. Now you want to put in your spa, your automated lights, your new heating system, it’s really hard to do that on a house that’s added 700 rooms. That’s how I think about the DAW.”

“I can see why no one in their right mind would undertake [building a DAW],” says Lex Dromgoole, CEO of Bronze, a company developing a new type of AI and Machine Learning-powered DAW. “If you add the fact that people can’t really make any money out of it because it takes so long to develop, you can see why there’s no innovation. I think that’s actually a big part of it — the economic incentives aren’t there.”

Joshua Hodge, founder and director of the Audio Programmer community — a YouTube channel, Discord server and events platform for plug-in developers — claims that things have also plateaued in the plug-in world. “One of the biggest hurdles used to be analogue modelling — being able to capture the warmth and expressiveness of hardware,” he explains. “From when plugins were first made up until about 2012, [it] was really about trying to get that sound back into these tools.” Hodge says that now analogue modelling has essentially been achieved and classic kit can accurately be re-created in the box, innovation momentum has been lost. “I feel like it’s hit a plateau in terms of creativity and where a lot of people are just creating the same thing. A lot of people are wondering: what is the next thing, what is it going to look like, how can [we] expand on the current capability of what we’re doing with a DAW? But I don’t think anyone has quite nailed what it’ll look like.”

“Is the DAW in trouble? I would say the DAW is in a very important maturation phase in its growth. In a way, I think the traditional DAWs need this kick in the butt to help solidify who they are.” – Scott Simon

David Ronan, founder of RoEx Audio — a new audio technology company building AI-powered music-making tools, echoes the frustrations of other developers. He explains that while the DAW has done an admirable job of recreating traditional studios, there “exists a degree of inertia within the industry that impedes transformative change. Over the years, I’ve encountered numerous roadblocks when trying to do something a bit unconventional yet potentially groundbreaking with traditional DAWs. It's left me exasperated at times, akin to attempting to install a Ferrari engine inside a Fiat Punto.”

While many of those within the DAW industry may feel frustrated, there’s also an argument that it’s the perfect example of design done right. If it ain’t broke, why fix it? With deadlines looming and a string of hardware devices attached, producers, artists and engineers simply want to sit down at their desks with their muscle memory intact. The DAW can be a sacred space, highly customised and tweaked to personalise the music-making experience and to remove as many hurdles and interruptions as possible when getting your idea from your head to your speakers. Surely innovating for the sake of it is more harmful than not innovating at all? After all, stability and dependability are both extremely important to the end user. That argument is fair, and long remained the dominating narrative. That is until 2020.

The pandemic saw billions of people restricted to their homes and, with it, an explosion of interest in music-making occurred. At its peak, US retailer Sweetwater was shipping 15-20,000 products a day, while companies like Ableton and Apple extended their free demo periods for curious new potential customers. We explored the impact of the pandemic on music tech in a piece in 2021, which dives into this period in more detail, but, suffice it to say, despite the music industry as a whole suffering terrible losses, music tech companies bucked the trend, some recording record sales, largely from a new, inexperienced user base who found themselves with time on their hands. Suddenly, a whole new market was circling DAWs, and it wasn’t those whose keyboard shortcuts were sacrosanct, but a new type of music maker, who wanted results quickly and complexities removed. “Now there are two worlds — the traditional DAW as we know it, and this new world,” claims Scott Simon.

This explosion of new creators also changed the landscape for music tech companies, as many saw a flurry of growth followed by a flurry of investment, leading to a series of mergers and acquisitions that have come to dominate the past 18 months. These include Native Instruments swallowing iZotope, as well as plug-in companies Brainworx and Plugin Alliance, inMusic acquiring Moog, Pioneer DJ acquiring Serato (subject to approval), and AVID being acquired by STG in August 2023. An excellent video titled The Private Equity Buyout of Music Tech by YouTuber and artist Benn Jordan goes into more detail on this trend.

As the floodgates opened, and new users arrived, they brought with them a change in expectation. Social media had already been a big part of the landscape online for over a decade, but DAWs and music-making remained a largely offline, solitary process. BandLab — an online DAW, and music-making platform — saw an opportunity. “I wanted to start BandLab in the first place as this idea that there wasn’t just a possibility to innovate on the creator side, but also on the social side,” says Meng Ru Kuok, the company’s CEO. “They call it GarageBand but people don’t get into garages anymore, everyone lives online. The way that people collaborate is very different.”

Tim Exile, producer and founder and CEO of Endlesss, a collaborative music-making app and platform, saw the same trend. “The 40,000-year history of music has been something we do together,” he explains over Google Meet. “[There’s been] a tiny exception in the last 100 years or so, where it’s turned into this industry that produces products that people consume.”

For Exile, the idea of the lone genius, operating with intrigue and mystery, will be replaced by more collaborative, fan-led artists who dismiss anonymity. “The archetypal operator in [the lone genius world] is Aphex Twin,” continues Exile, “who really built his brand on this complete mystery and intrigue, driving this crazy level of curiosity around what he was doing. I don’t think you’d really be able to build the Aphex Twin brand now.” Exile sees newer fans wanting more connection with their favourite artists. “It’s interesting to look at how Fred again.. has built his brand, which is much more participatory. There isn’t really any intrigue there. It’s almost the opposite.”

“There’s a rising tide that will lift all ships, but I do believe that the specialised [DAW] workflows are very resilient and will always stay there, but they’ll add additional things to their arsenal” Meng Ru Kuok, CEO of BandLab

BandLab’s huge surge in users — now at well over 60 million — may hint that they’ve backed the right horse, but Kuok doesn’t see this as a transition away from traditional DAWs, simply an augmentation. “If you think of the huge influx of people making music, there are more people than ever before who need to finish songs,” he argues. “There’s a rising tide that will lift all ships, but I do believe that the specialised [DAW] workflows are very resilient and will always stay there, but they’ll add additional things to their arsenal.”

Exile agrees: “I don’t think the future of the DAW is threatened in any way. They’ll always sit at the top of the pile of musical excellence,” he explains. If the future of music-making is indeed in the cloud, where the emphasis lies on seamless Google Docs-style collaboration and more accessible tools, it opens the door for another largely cloud-based technology to thrive in this new ecosystem: AI.

Despite AI being used in music-making for many years, even decades previous — something we discussed in detail in our three-part AI Futures series in 2021 — when OpenAI launched DALL-E 2 in April last year, and later ChatGPT, the world gasped as AI, or more accurately machine learning, appeared to be able to ‘create’ from thin air. Exaltations around AI’s impact on everything from healthcare, war, the economy, climate change, and culture have been widely documented, for better and for worse.

For music, more widely, legitimate concerns around copyright and intellectual property continue to be debated as AI tools and platforms launch by the day, many trained on copyrighted content without the permission of the rightsholders. It’s a messy situation that’s changing rapidly, with looming legislation from both the EU and US governments poised to define how AI and copyright coexist over the next decade and beyond. For now, it’s a Wild West with everything from fake Drakes to GrimesAI, conflicting views and Discord servers full of unlicensed voice models.

For the DAW, the story is more nuanced. What might AI and ML inside a DAW look like? Will we simply ask ChatDAW to ride the vocal fader for us? Maybe we’ll ask it to balance the mix and remove any frequency masking so we can focus on the creative side. Perhaps it’ll be an eight-bar loop we ask it to build an arrangement around, similar to out-painting. Maybe the days of clicking tiny automation nodes will be gone forever — dare we dream?

That future is closer than you might think — a website called WavTool has built a very rudimentary music-making software featuring a chatbot that can complete tasks like adding MIDI notes in a certain key, to tweaking FX, adjusting signal paths, adding sidechain compression, and coming up with drum patterns, all through text prompts alone. It’s basic, and sometimes it’s very bad, but the proof of concept is impressive. A chatbot inside a DAW, your own personal studio assistant who’s learned everything about the way you work, feels like a logical and incredibly useful way for this tech to develop. How likely that is in the current DAW ecosystem remains to be seen.

There are two more ways AI and ML could shape the future of the DAW. One is voice modelling, which is when an AI model is trained on a person’s voice using studio-quality acapellas. The algorithm detects millions of data points such as the person’s timbre, tone, accent, vocal range, their breaths between words — every single aspect of what makes a person’s voice identifiable. That model is then stored on a server, usually in the cloud. A user can then transform their own vocal recording into that person’s voice by applying those characteristics to their own recording. This technique is already being adopted outside the DAW, with the GrimesAI project the best example. Others include DJ Fresh’s Voice-Swap, which has licensed the voices of famous singers for producers and artists to use in their tracks.

What’s really interesting is when you apply this concept, not to the human voice, but to a mix or a producer’s style. What if you could apply the vibe of a certain producer to your track? Will we start seeing Splice-style stores pop up selling a Motown model, or a Daft Punk Homework-era model, that automatically applies hundreds of different tweaks across your mix — from monoing sounds, adding EQ settings, compression settings, reverb, delay, and all the variables that make up an era’s sonic identity?

It’s an exciting idea and is absolutely possible in the near future. Imagine instead of modelling famous compressors or EQs, we’d model not just the gear used but the studio’s ambience, the engineering techniques, the technological limitations of the time, the typical microphone placement, the acoustic reflection characteristics of the most popular carpets and rugs of the era, how many cigarettes a singer may have smoked that day, and many thousands more variables we can’t currently fathom.

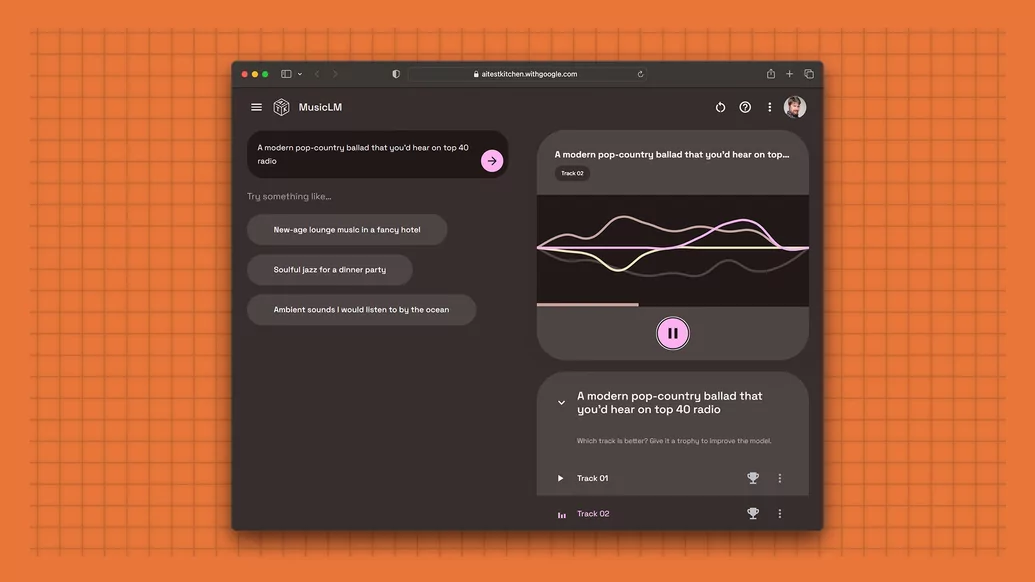

Another way this technology could become part of the future DAW toolkit is through generative AI, which is the process of creating content from scratch — be it an image, text or sound — usually using a prompt as a source (it's something we covered in our recent feature on the future of sampling). While voice modelling technically is generative AI in that it’s creating something essentially using a prompt — the prompt just happens to be another voice — it’s more commonly come to reference DALL-E 2 style text-to-content generation. Google’s MusicLM and Meta’s AudioCraft are two examples of emerging tools that could eventually evolve to be inside a DAW.

For most artists, though, this kind of one-button solution to music isn’t what they’re looking for. Artists want to be creative and they want to have control over the creative process. For TikToks, or podcast music soundtracks, this throw-away generative music might work, but for artists and producers with their own unique identity, it’s hard to see the one-button style solution working. What’s more likely, is that generative AI replaces steps within the music-making process, rather than replacing creativity entirely.

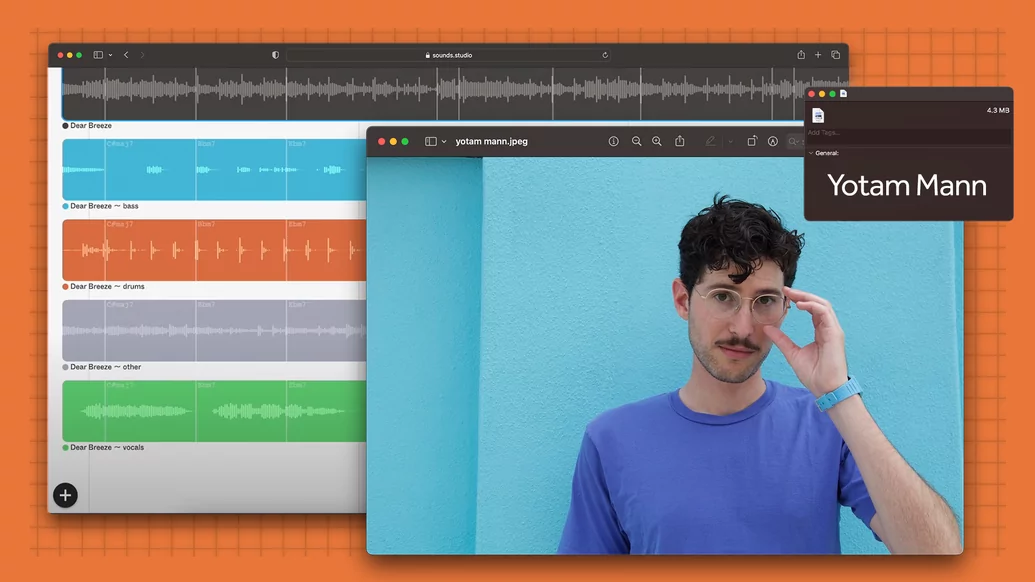

“Musicians are after their own sound,” Yotam Mann explains, the co-founder of Never Before Heard Sounds (NBHS), a machine learning-powered DAW that includes features like stem separation, text-to-audio tools and AI voice modelling. “You’re never going to feel ownership of music made by tools that oversimplify the process. You want to find your own creative path in this kind of ecosystem — that’s how people create and discover their own sound. Our goal as a platform is to make that possible.”

“AI algorithms are extremely tied to the hardware, and typically only run on very specific kinds of GPUs. So when we thought about how we actually deploy this [technology], and get it into musicians’ hands, the browser was kind of our only option.” — Yotam Mann, co-founder of Never Before Heard Sounds

To build their platform, NBHS didn’t opt for an offline, siloed app, instead choosing the browser for their brave new world. Having spent time building Magenta Studio with Google, Mann learned that the browser allowed for far more flexibility and support, especially when AI was incorporated. “AI algorithms are extremely tied to the hardware, and typically only run on very specific kinds of GPUs,” he explained. “So when we thought about how we actually deploy this [technology], and get it into musicians’ hands, the browser was kind of our only option. By the browser, I mean both the combination of your browser and cloud rendering.” NBHS, now called Sounds.Studio, recently came out of private into public beta. You can try it here.

David Ronan of AI plugin company RoEx agrees that the browser feels like the logical pivot for DAWs and music-making tools: “At present, the array of advancements in AI technology does not blend seamlessly with DAWs, leading to a noticeable divide between the desktop and browser environments”.

Ronan argues that while traditional DAWs shouldn’t abandon their desktop apps in favour of the cloud, there are significant advantages in using the browser to adopt new technology. “A browser-based DAW could enable a host of powerful features that are challenging to implement in a traditional desktop environment,” he continues. “These might include real-time collaboration between artists located anywhere in the world, seamless integration with AI and ML services, immediate access to a vast library of online samples, and automatic backup and synchronisation of projects across devices.”

Online samples within a DAW are already commonplace, with Splice’s Bridge plugin and Loopmaster’s Loopcloud offering a kind of workaround. More recently, Image-Line announced FL Cloud Sounds, which introduces sound packs pulled from the ’net, which are previewable and browsable right there inside the DAW. In fact, as in the last week there have been two major developments in this area. Firstly, Image-Line introduced stem separation and AI mastering inside their popular DAW (has the cloud DAW revolution already begun?) And, secondly, Bitwig and PreSonus introduced a new DAW format that allows cross-compatibility between Bitwig and Studio One projects (is someone reading my drafts?)

“I believe we have a responsibility to support ethical, legal use of content as well as create tools that are created ethically and legally. There’s a responsibility on the DAWs to come together to support the right traceability...” – Meng Ru Kuok, BandLab

Another new launch that could point towards a more connected DAW is BandLab’s acquisition and rebrand of the classic DAW Cakewalk — with Cakewalk Next and Cakewalk SONAR. It’s not yet clear what features will be included, but given BandLab’s mobile and social approach, you’d expect the newly revamped software to include some kind of cloud-based aspect.

It’s worth pointing out that the browser isn’t some fix-all solution to the woes of the DAW, far from it. It introduces its own problems, with latency, multitrack I/O capabilities, and third-party plugin support being three glaring issues. But there are many benefits to a hybrid approach, from a social and collaboration perspective. As both BandLab and Endlesss allude to, integrating emerging tech like AI, pushing updates faster and easier, as well as troubleshooting and bug fixing, it feels like most DAWs will adopt some form of cloud connectivity in the near future. Offloading heavy CPU loads to the cloud also feels like an added bonus. How long until cloud computing replaces DSP cards entirely?

DAW companies have historically avoided blame for the content that’s created inside them. And that’s fair. But if they do move more online, and with the onset of generative AI and the ethical minefield it throws up, should DAWs be more aware and proactive of their role when it comes to copyright infringement? BandLab’s Meng Ru Kuok thinks so. “I believe we have a responsibility to support ethical, legal use of content as well as create tools that are created ethically and legally,” he explains. “There’s a responsibility on the DAWs to come together to support the right traceability — we can’t just leave it all to the DSPs [Spotify, et al] to figure out. Everyone has a part to play in supporting the next evolution of this industry.”

Whether the DAW remains the North Star, undeterred as emerging technology disrupts creative tools elsewhere, slowly begins to shift course to future-proof itself for the next 20 years, or is completely redesigned from the ground up, 2023 feels like an inflexion point. The scene is set for a transformation, and the room is divided on how it will play out. “Is the DAW in trouble?” asks pro audio consultant Scott Simon. “I would say the DAW is in a very important maturation phase in its growth. In a way, I think the traditional DAWs need this kick in the butt to help solidify who they are.”

“The next three to five years promise significant transformations in how music is composed and consumed,” says RoEx’s David Ronan, adding that as AI and machine learning tech advances, DAWs may struggle to keep up. “Current systems may not easily accommodate this innovative, interactive framework. In response, we might see the development of new tools, methods, and software built explicitly for this purpose.”

“This is not a zero-sum game,” adds Endlesss’s Tim Exile. “We’re seeing double-digit growth in the number of people making music every year. That growth is going to be driven by tools that emphasise fun above perfection, but there’ll always be a path of progress. And the DAW is going to be quite a way down that path.”