Can UNESCO help safeguard techno culture?

A new initiative, started by the founder of Love Parade, aims to have Berlin's techno scene recognised as a cultural practice, supported and preserved by UNESCO. DJ Mag speaks to those behind it and others to learn the significance and possible outcomes of giving techno world heritage status

It’s a grey, wet Tuesday morning in Berlin, and inside an unassuming building in Wedding, a fourth-floor apartment is buzzing with activity. It’s the home of Dr. Motte, and the campaign headquarters for his hugely ambitious project.

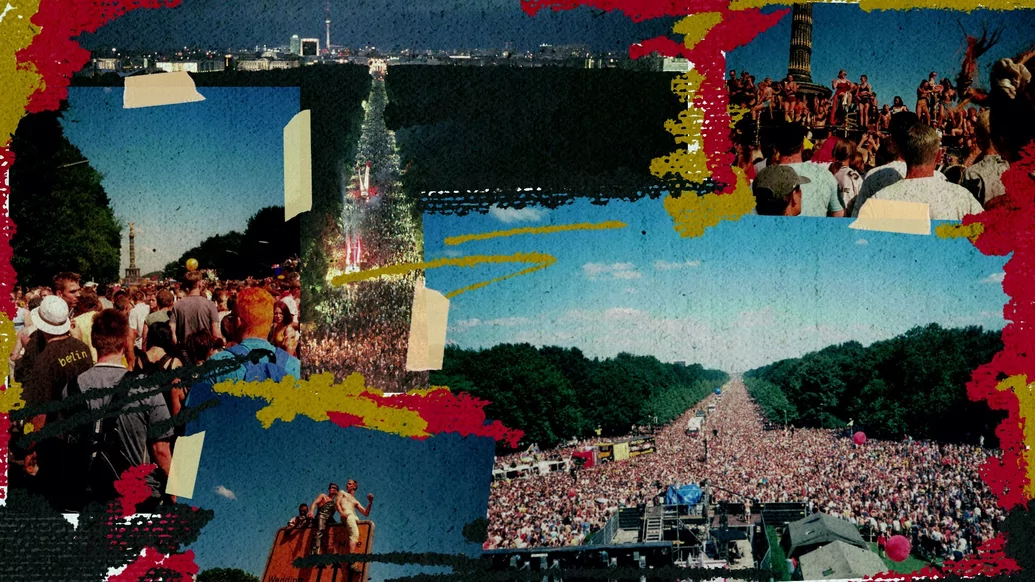

The man responsible for Berlin’s first acid house parties in the late-1980s, and the Love Parade, Motte co-founded Rave The Planet in 2020 to bring the massive street party back to Berlin for the first time since 2010. A date for the Rave The Planet Parade is set for 9th July 2022, and plenty of work is still needed to pull that off, but the group’s attention is also focused on something bigger — inscribing Berlin techno to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) Convention.

This annually-updated list recognises traditions, values and identities handed from generation to generation through spiritual, skilled or intellectual practice. Submissions pass at a national level, before an intergovernmental panel of experts gauge suitability for worldwide inclusion based on specific criteria. Among other things, they need proof of a ‘safeguarding roadmap’ showing what actions will be taken to support the culture, consent from the community involved, and a unique, recognisable identity.

“It would mean that the government and authorities have to help the culture continue,” Motte says, of a successful ICH bid. “It would mean easier access to money from the state for support... if we have that status, we could support clubs with lower taxes, and it could affect building and trading laws.” There’s a long game to the bid that goes beyond Berlin’s city limits. “To get to the status of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage for techno in Germany, this is what we want to work towards. And then Europe. But first, we start in Berlin.”

Preparing for this, Rave The Planet engaged in extensive research into electronic music in Berlin for the bid’s lengthy submission form. A video has been produced, featuring prominent players like Ellen Allien, Dimitri Hegemann and Alan Oldham discussing what makes the scene significant. While applying for ICH status is free, time spent on the bid is not. Fundraisers have helped cover the costs so far, including an exhibition about Berlin in the ’90s and the Love Parade’s 30th anniversary, and a series of charity EPs featuring music from DJ Rush, Joy Kitikonti, Saytek and Christian Smith, among others.

“We’ve got the UNESCO application ready... it could take two, five or 10 years to get a final outcome,” Motte tells us over morning coffee at his kitchen table. “UNESCO seems supportive, because what they like to have is not just handicrafts — knitting or something — they want to have something urban, young.”

To many dance music fans worldwide, Berlin’s pro-techno stance might beg the question: why bother? Surely the scene doesn’t need UNESCO to recognise it, or even save it? Rave The Planet’s Tomasz Guiddo is passionate about this. “If we don’t do something now and let the whole scene be recognised just on commercial and entertainment aspects, it will be taken over by whoever has more money,” he says. The concern is easier to understand when you consider that, between 2010 and 2020, more than 100 Berlin venues closed for good and property values more than doubled, the latter according to Deutsche Bank.

“This leads to more segregation and divisions. It puts people in boxes through marketing tools, telling different target groups what is and isn’t for them based on prejudged and forced tastes, preferences and financial status; just like any other commercial product. This is exactly the opposite of what clubbing culture stands for,” he continues. “And in all this, the smaller clubs, if they aren’t wiped out, will struggle to survive. They will be — or actually are, already — more concerned about ticket sales, rents, taxes or their complaining neighbours, than putting a good programme together and fulfilling their cultural mission.”

Guiddo cites the aims of ICH inscription that would benefit techno culture in Berlin. These include lowering “obstacles and requirements for the opening and maintenance of cultural venues, meaning clubs”, an increased likelihood of administrative-level decisions around sound and safety, and the protection of specific locations, from venues to festival sites.

There are problems, though. UNESCO has little direct power, and relies on influencing governments to support the assets it recognises. Some in Berlin are sceptical about the bid, because ICH inclusion only works with political support at a national level. DJ Mag approached Berlin’s ClubCommission for comment, and while no formal statement was issued, a spokesperson described unease about the risk of “museumification”; positioning techno as an exhibition piece rather than evolving cultural force, and uncertainty at the value of the payoff, considering the work involved.

Tim Curtis, UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Secretary, spoke with us from his Paris office. He reiterates the purpose of the Convention — ensuring new generations experience inscribed elements as living culture, and encouraging more participation, development and evolution.

“A lot of it is about valorising. You could say reggae music doesn’t need valorising, but it can give people a sense that they have something really valuable — recognition on a global level that they are contributing to society and civilisation,” noting the successful 2018 bid to recognise reggae music in Jamaica.

“Belgium has one called ‘Shrimp Fishing On Horseback’. There were only a couple of people, a few families, left doing this,” he continues. “Then they inscribed it, and now there are summer schools running with people learning how to practice it, so this practice will survive now. And that’s without heavy state intervention — just a little support.”

We contacted the team behind the 2018 inscription of Jamaican reggae. Their bid demonstrated how earlier forms of music on the Caribbean island were spliced with North American, Latin and African tones, creating a sound unique to communities in Kingston, which was then embraced by a wide cross-section of society. ICH approval commitments were made, such as addressing gender imbalance in reggae culture and the industry, and using music as a means to improve social mobility and make communities more peaceful.

Unfortunately, the team behind the Jamaica bid were unable to contribute to this article because members sit on the ICH intergovernmental committee, and so could be involved in judging the Berlin case.

Although 180 nations have ratified the Convention so far, the UK is not among them; nor is the US, Canada, New Zealand or Australia, preventing direct applications for any activity in those countries. But they do subscribe to others. This November, Belfast became a UNESCO City of Music based on a variety of factors — the ability to host national and international festivals and events, specialism in music education, and a spread of large and small venues, recital and rehearsal spaces.

“We are excited about what this means for the city and our musicians across all genres, and look forward to the forthcoming musical events and projects which will come as a result,” says Genevieve Taylor of Free the Night, a campaign for more liberal licensing laws and recognition of electronic music as art in Northern Ireland. “It’s so important to the future of our night-time economy to have our artists and creative communities nurtured.”

For some, focusing on the outcomes of ICH inscription is missing the point, or at least jumping the gun. Walter Leimgruber is an academic with the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and European Ethnology at the University of Basel. Between 2010 and 2020, Leimgruber was on the steering committee for cultural heritage decisions in Switzerland. He explains that although the UNESCO Convention was ratified in 2003, the first items were only added in 2008. “It’s something you can only really see over the long term, not in the short amount of time we have had this for,” he tells us.

This is particularly true for elements not immediately at risk of disappearing. The results of ICH status are more visible with centuries-old traditions that need fast, direct intervention to survive. But he maintains the inscription of techno in Berlin would be significant, and easy to imagine. While on the committee, Leimgruber and others were involved in a discussion about electronic music, which helped pave the way for techno and street party culture in Zurich to be added to Switzerland’s list of ‘notable traditions’ in 2017. The country’s national precursor to ICH, he tells us that contemporary youth cultures have the potential to safeguard the Convention itself by keeping it relevant.

“In the discussion about techno and street parades, we considered how our lives today are so impacted and tied to a worldwide, connected way of living, and culture that has nothing to do with a certain ethnic group or a geographical location,” Leimgruber recalls. “Many activities are now spread across the world and are practiced by many different groups, and have nothing to do with regionalism. This main string of a modern way of living, of today’s engagement in culture, isn’t visible in the ICH list. But we need to see how important this is for people all over the world.

“One of the reasons we singled out Zurich is that the street parade brings people from all over the world. Zurich changed a lot through this, it was quite a sleepy city until the 1980s, and then it changed. It woke up, and we can align this with the street parade, with techno,” he continues.

The reaction to a form of dance music receiving traditional status was mixed. “Many people said, ‘This is not tradition, because tradition must go very far back’. Normally there is a discussion around whether it has been alive for two generations or more, and a generation is usually seen as 25 years. But what is a generation in popular culture? It is perhaps the youth span of a person, so between the ages of 15 and 25 — eight to 10 years, and no more.”

Ensuring the ICH Convention represents modern, globalised culture is important for more reasons than relevance. Celebrating activities that unify nationalities, sexualities, ethnicities, and more highlights our similarities, rather than differences. It has the potential to encourage acceptance and understanding.

For Leimgruber, Rave The Planet’s end goal — inscribing techno in multiple focus countries for club culture — would be a good example of this. It could also encourage better attitudes towards participants. “If this is accepted, then you have a new picture of young people. You don’t need to problematise what they’re doing, but instead support them and help them build.”

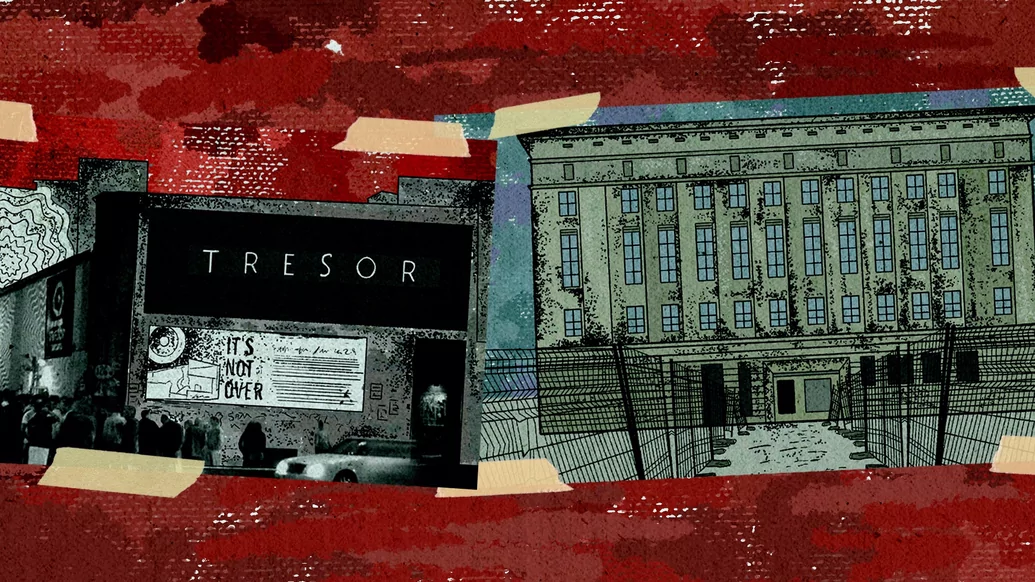

Alan Oldham, aka DJ T-1000, is regarded as one of the core early figures of Detroit techno and a member of Underground Resistance. Having lived in Berlin for the last seven years, Oldham was drafted to appear in Rave The Planet’s ICH bid film. “If techno is recognised as a cultural asset rather than just hedonistic party or drug music, it would help the artists, labels, producers and promoters greatly,” Oldham tells us. “It would maybe also have the same effect as historical landmarks do, protecting some important venues, like Tresor, from encroaching gentrification. It would be very helpful globally. I am always reading about how venues like fabric in London are under attack from real estate developers. If these venues were somehow culturally protected, it would be great.

“I could definitely see Detroit applying,” he continues, on how other cities could make a bid for ICH status. “It is the birthplace of techno, but there’s a racial element in Detroit that Berlin doesn’t have to contend with. I’ve often said that, if not for race, Detroit would be known as a music city like Nashville is. But we get coded right-wing language like ‘murder capital’ and ‘Democratic hellhole’, i.e. Black. It would take a lot for local authorities to recognise us.”

Uncertainty at what ICH inscription means for Berlin techno makes drawing conclusions difficult. Certainly, the culture meets requirements and suits the Convention’s own aims. Agree with these efforts or not, though, recent years have revealed a glaring gap between values based on economics and those grounded in culture. Perhaps recognition from an international body can encourage policymakers to take techno seriously as more than a night out; potentially emboldening and inspiring other communities to follow suit, however they can.