How Renegade Soundwave's ‘The Phantom’ paved the way for the UK's gritty rave sound

This evergreen breakbeat hardcore missive influenced the likes of The Prodigy and the whole of the early UK rave scene. Ben Murphy charts its story...

“I saw that record go from street level and get bigger and bigger, and there was no video for it, no promotion, nothing,” says Renegade Soundwave’s Danny Briottet, remembering the phenomenal impact of his group’s rave anthem ‘The Phantom’. “At the time, I knew all the guys in places like Street Sounds and all those shops. I used to give them white labels and they said, ‘Yeah Danny, this is going to blow up. We know when something is going to blow up’. Then it started to happen, and every pirate radio station you’d put on, you’d hear it, or in people’s cars driving past. It was a massive buzz, because at the time, it was really real. It was that whole DIY thing. DJs you didn’t even know were playing it. That was wicked.”

‘The Phantom’ is a perennial dance classic — an early breakbeat track that arrived just as acid house was evolving into its own new UK variant, hardcore. Rinsed at warehouses, in clubs, on pirate radio at the time of its release and for many years afterwards — and by DJs across the board even to this day — its raw funk, explosive mixture of influences and distinctive sound make ‘The Phantom’ universal.

A favourite of Josh Wink, DJ Marky, Andrea Parker and Photek, it has a broad appeal. “When you hear interviews with Liam from The Prodigy, he always talks about Renegade Soundwave,” Briottet says. “The Chemical Brothers, Grooverider, they say that we were a big influence.”

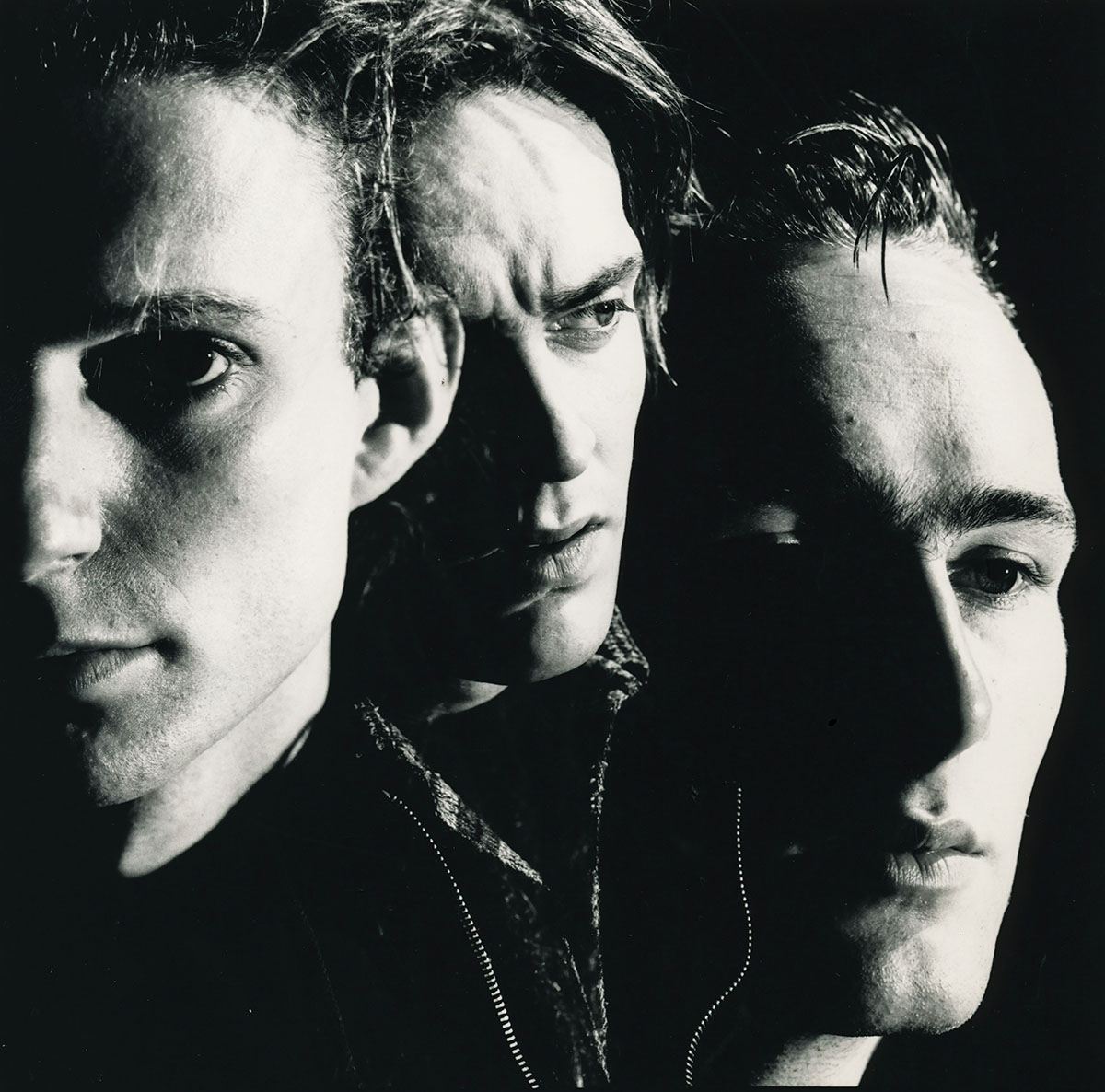

The three members of Renegade Soundwave — Danny Briottet, Carl Bonnie and Gary Asquith — had formed in London in the latter half of the ’80s, and shared an appreciation for hip-hop, punk and dub, influences which decorated the industrial, cut ‘n’ paste aesthetic of early single ‘Kray Twins’. They signed to Daniel Miller’s respected electronic imprint Mute in 1988, and the prevailing acid house sound of the time began to make its presence felt in their output for the label, such as the single ‘Biting My Nails’. But their next single for Mute, ‘Space Gladiator’, with ‘The Phantom’ on the B-side, was something else. While the lead track was a loose-limbed indie-rock track with a dub bassline and squalls of guitar, ‘The Phantom’ had a relentless, snapping breakbeat snare like little else of the time, and only sparse vocals. Its trippy FX and metallic percussion gave it a minimalist vibe clearly geared to the dancefloor, and the undulating bass groove showed the strong influence of reggae on the band.

Danny Broittet grew up in Ladbroke Grove, and after a while living in Algeria where his parents went for work, he returned to West London. Living among the soundsystems and reggae music of the area’s Jamaican community, it was inevitable that the sound would make its way into Renegade Soundwave’s records. “Reggae was a huge part of growing up,” Briottet says. “Me and my mate Baz were going to soundclashes and all kinds of things while we were still in school. Everything with the bass, that just became normal. From that, we mixed up beats from hip-hop, bass from reggae and the indie-punk attitude that we grew up with as well.”

In the late ’80s, hardware samplers were becoming affordable, and sampling opened up a new world of musical possibilities for Renegade Soundwave (and many other artists).

“We just embraced samplers as soon as we found out about them really, which would have been a couple of years before, in ’86, ’87,” Briottet says. “From a DJ’s perspective, it was like, ‘Wow, you don’t need two records to cut up any more, you can just sample whatever you want and fuck around with it’. We just had the old Akai S900, with the tiny slot and a minute-and-a-half of memory at the most. You had to strain that, but at the time we thought it was magical what you could do. We were let loose in the studio, and you’d bring all your musical baggage with you. Sampling allowed you to dive into all of that. It was much easier in the beginning, because there was all this stuff we wanted to sample. Later on, it became harder because you’d used it all up, and sampling laws came in.”

‘The Phantom’ was made with this magpie mentality. Created while Renegade Soundwave were working on their debut album for Mute, ‘Soundclash’, at the label’s recording studio on London’s Harrow Road, it was the product of an intense period of productivity late one night, in which Broittet sketched out the bones of another proto-hardcore track, ‘Ozone Breakdown’, a lesser known but equally deadly early rave monster. “There was another room in the studio,” he says, “a programming room, and I used to go in there on my own. I did ‘The Phantom’ and ‘Ozone Breakdown’ in about three hours, the basis of them. I did both of the beats and the basslines, the bits and bobs. It was one of those nights. Everybody else was in the other room working away with [record producer] Flood, and I just went in and did that. Then we developed them a bit together, but they were really quick tracks to do, both of them. These days, people labour over things, but there was no Logic and all that stuff. You had basic equipment so you couldn’t piss around as much as you can now. It was all pretty quick.”

One of the most striking moments on ‘The Phantom’ is its sample of The Clash, a loop from the seminal punk band’s early single, ‘White Riot’. It’s unmistakable, and adds a delicious extra anti-establishment layer to the track’s already rabble-rousing rebel concoction. Renegade Soundwave were huge fans of the band, who were also from West London and had incorporated reggae and hip-hop in their own music. Sampling them came from a place of deep respect, and was in the lineage of The Clash’s DIY spirit and firebrand fervour.

“We grew up with The Clash,” Danny Broittet says. “As a kid, a 15-year-old, I used to follow them. I absolutely loved them, they summed everything up that you were feeling, plus they were into reggae and they looked great. We sampled ‘White Riot’, and we gave a white label to [bass player] Paul Simonon, at some event. We said, ‘Listen Paul’ — we didn’t know him at the time — ‘we’ve done this thing and sampled you on it, hope it’s going to be alright, it’s done out of respect’. We gave him the white label and we bumped into him again. He said, ‘Yeah I’ve played it, it’s alright, you can use it’. Then Mick Jones came up to me at a rave on Latimer Road, and said, ‘Are you Danny? I really like your stuff’. I couldn’t believe it.“I had their poster on my wall when I was a kid. I said, ‘I never imagined in a million years that you’d come up to me and say you liked my stuff’. Then, shortly after that, do you remember when Norman Cook did ‘Dub Be Good To Me’, with the ‘Guns Of Brixton’ bassline? The Clash sued him, and I remember Paul Simonon was on the radio and they were talking about Beats International, saying, ‘Why did you sue them? Are you not into sampling, do you think it’s wrong?’ Paul said, ‘I don’t think it’s wrong in principle, but he took the piss, he never asked, he just did it, so we sued him. On the other hand, there’s a band called Renegade Soundwave, and they came to me and gave me a record, saying, ‘Here you are Paul, would you mind listening to this?’ Because they came with respect, we let them use it.’ All the royalties from the Norman Cook thing went to The Clash, but they let us have it. Which was wicked, for us being young kids at the time. Later on I became really good friends with the Big Audio Dynamite guys and worked together with Dan Donovan, Greg and Don.”

‘The Phantom’ was made on rudimentary electronic equipment. As well as the aforementioned Akai S900 sampler, Briottet played the bassline on a Juno 106 synth, mixing it with a sine wave sound for extra beef. There was a Moog Prodigy too for the whooshing effects, but crucial to the record’s distinctive character was the Korg DDD1 drum machine, an underused but — in Briottet’s opinion — powerful bit of kit for altering and condensing drum hits.

“I loved it, but no one else really used it,” he says. “It had a certain swing. Everyone else was using the Akai MPCs, which I never had, but I really liked the DDD1 because I was a drummer before. I didn’t like programming the Roland drum machines, although they sounded great, because you just pressed a button here and you watched the lights come on. It was like doing a crossword, but the DDD1 had pads so you could actually play it. It had a tiny sampler in it, so you could sample something. For example, the snare on ‘The Phantom’ was off a James Brown record, but it didn’t sound anything like James Brown.

“That drum machine would fuck up the sound so much, it would compress and condense it. That was one of the things I liked about it. The beat for ‘The Phantom’ and ‘Ozone Breakdown’, both are played on that drum machine, but only as a trigger. There were no good internal sounds on it. I just like the way it felt and the way it quantised. You could work really quickly on it.”

Renegade Soundwave’s fan-base varied considerably either side of the Atlantic. In America, when they toured, they were favourites of the alternative rock and college radio scene, but in the UK, their appeal was broader, as ‘The Phantom’, ‘Ozone Breakdown’ and another track, ‘Thunder II’, were embraced by the rave scene.

“In America we were perceived as following Depeche Mode,” Briottet says. “We did well over there, but it was more the vocal side of it. When we played over there, the audience was pretty much white college and skate kids, whereas here it was much more mixed. We had the indie thing here as well, as well as the street thing, which those tunes really were. I didn’t necessarily think we were going to direct it at the rave scene or anything, we just did what we did and things got picked up by different sections.”